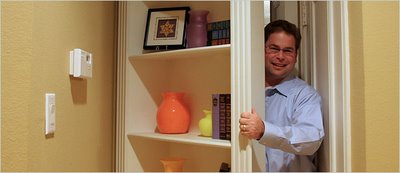

[Image: “Louise Kircher raises the staircase in her home in Mesa, Ariz., to reveal the secret room behind it.” Mark Peterman/New York Times].

[Image: “Louise Kircher raises the staircase in her home in Mesa, Ariz., to reveal the secret room behind it.” Mark Peterman/New York Times].

“On a recent Saturday morning,” The New York Times writes, “Cami Beghou, 13, pushed the right side of the tall, white bookcase that is built into one of the powder-pink walls in her bedroom. The bookcase, holding rows of books, a stuffed dachshund and a volleyball, silently swung outward, revealing a tiny, well-lighted room. Containing a desk, a chair and a laptop computer, it serves as her study area.”

Apparently, the family gets a kick out of fooling people – it’s suburban normality in an age of architectural dissimulation: “When the home inspector came by to examine the house, our builder shut the bookcase, hiding the room. The inspector went up and down the stairs a couple times – he knew that something was unusual – but he couldn’t figure out what was there.”

[Image: “David Lee of Plano, Tex., got a bookcase door to hide the mess of his workroom, but also because he had wanted a secret room, he said, ‘since watching Scooby-Doo way back when.'” Misty Keasler/New York Times].

[Image: “David Lee of Plano, Tex., got a bookcase door to hide the mess of his workroom, but also because he had wanted a secret room, he said, ‘since watching Scooby-Doo way back when.'” Misty Keasler/New York Times].

And therein lies a Kafka novel for the suburban twenty-first century, in which a real estate appraiser from a national bank is sent to a small town in the cloudy hills of central Pennsylvania to find that all the houses he’s meant to review are similarly unusual: the outsides are bigger than the insides – or vice versa – and indoor corridors trace around what should be whole wings the man can never find. He returns to his small room at the Comfort Inn every night, and, in between watching endless Bruce Willis films on the hotel television, he begins sketching out the neighborhood from memory…

Then he realizes something…

In any case, The New York Times adds that these secret rooms in suburbia have become increasingly popular: “The Beghous’ architect, Charles L. Page, who is based in Winnetka, said he had designed seven other houses with hidden rooms since 2001, after designing none in his previous 40 years as a residential architect. ‘Absolutely, there has been an increase,’ said Timothy Corrigan, an architect and designer in Los Angeles, who noted that he has been practicing for 12 years but was not asked to design a secret room until four years ago. Since then, he has created five.”

Unfortunately, there is no mention of whether anyone has commissioned secret rooms accessible only from other secret rooms – M.C. Escher, Architect, perhaps – or complete, non-intersecting houses built in parallel to each other on the same small lot. Otherwise inconceivable geometries in home improvement form. Knotville.

(Via Archinect).

[Image: Edinburgh, as photographed by

[Image: Edinburgh, as photographed by  [Image: The

[Image: The  Tomorrow morning BLDGBLOG rolls itself out upon the American interstate highway system to make its slow way over to the apocalypse of Los Angeles – via Chicago, Denver, Boulder, and Springdale, Utah, where a few pints of

Tomorrow morning BLDGBLOG rolls itself out upon the American interstate highway system to make its slow way over to the apocalypse of Los Angeles – via Chicago, Denver, Boulder, and Springdale, Utah, where a few pints of

Finally, Christian Kerrigan wants

Finally, Christian Kerrigan wants

We wish him luck, as well.

We wish him luck, as well.

[Image: “The arches that form the catacombs beneath the McMillan Reservoir were crafted from unreinforced concrete, which means they couldn’t support construction above them.” Photo by Robert Reeder for the

[Image: “The arches that form the catacombs beneath the McMillan Reservoir were crafted from unreinforced concrete, which means they couldn’t support construction above them.” Photo by Robert Reeder for the