The German town of Dessau, home of the Bauhaus, may someday construct its own Great Pyramid.

“The pharaohs may have set the standard,” the Telegraph reports, “but German entrepreneurs are hoping to challenge Egypt’s pre-eminence in monumental self-indulgence by building the world’s largest pyramid.”

The Telegraph somewhat cynically continues, explaining that this “improbable plan is based on the belief that people will pay to have their ashes encased in the concrete blocks used to construct the monument.”

The Telegraph somewhat cynically continues, explaining that this “improbable plan is based on the belief that people will pay to have their ashes encased in the concrete blocks used to construct the monument.”

If that does turn out to be the case, however, then these German entrepreneurs “will be rich beyond the wildest dreams of even the most ambitious pharaoh.”

The blocks are expected to be up to one cubic metre in size and, given that the volume of the completed pyramid is likely to be in excess of 40 million cubic metres, it could ultimately bring in £13.2 billion.

Almost literally unbelievably, we read that an “international jury” will select the Pyramid’s final design – and that the jury “will be headed by the Dutch architect Rem Koolhaas.”

In any case, the concrete structure itself – why not granite? let’s please build huge structures out of stone again – would act as a “memorial site” for people “of all nationalities and religions.”

You don’t actually have to be buried there, meanwhile; you can “opt to have a memorial stone placed instead.” Your stone can even be “designed with any number of colors” – instantly transforming the Great Pyramid into a badly weathered mountain of tinted concrete, cracked and stained more and more every winter as it stands in the heart of an east German floodplain.

Still, the entrepreneurs are optimistic:

Still, the entrepreneurs are optimistic:

The Great Pyramid will continue to grow with every stone placed, eventually forming the largest structure in the history of man.

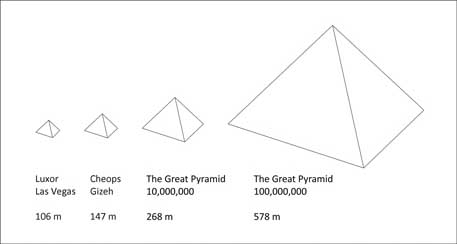

So how large is large?

The original plans called for “an overall height of some 1,600ft,” the Independent reports, “but the proposal has already been dramatically scaled down. The revised plans are for a pyramid of some 492ft.”

1) What does Michiel think of this? 2) Will it cause earthquakes?

(Thanks, John!)

[Image: The internal structure of maple leaves, via

[Image: The internal structure of maple leaves, via  [Image: A leaf, via

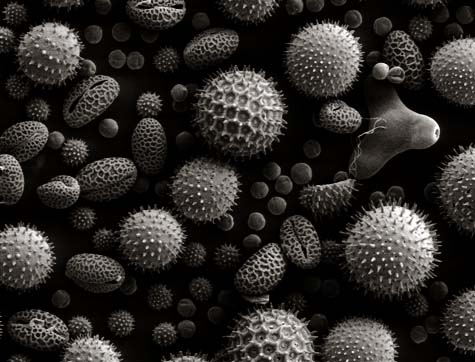

[Image: A leaf, via  [Image: Pollen, via

[Image: Pollen, via  [Image: A field of barley, via

[Image: A field of barley, via

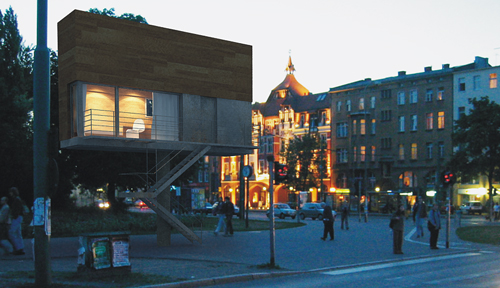

[Image: The

[Image: The

[Images: The

[Images: The  [Image: The

[Image: The  [Image: The

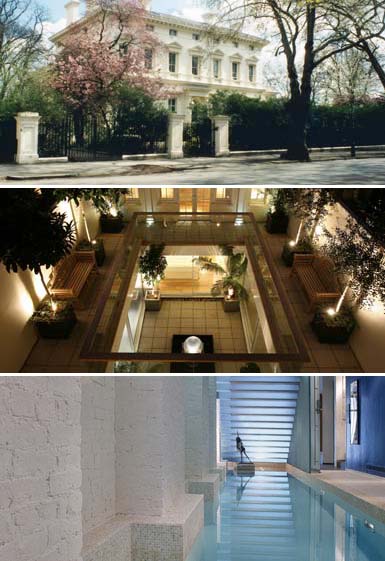

[Image: The  [Images: London houses and their subterranean extensions; all photos via the

[Images: London houses and their subterranean extensions; all photos via the  [Image: A scene from a film called “

[Image: A scene from a film called “ [Image: Fishermen on Lake Tanganyika, via

[Image: Fishermen on Lake Tanganyika, via  [Image: J.M.W. Turner, The Dogana and Madonna della Salute, Venice, 1843; for more, see

[Image: J.M.W. Turner, The Dogana and Madonna della Salute, Venice, 1843; for more, see  [Image: The South Tower of the World Trade Center on 9/11; photographer unknown].

[Image: The South Tower of the World Trade Center on 9/11; photographer unknown]. [Image: An aerial view of Ground Zero, taken on September 23, 2001, by NOAA’s Cessna Citation Jet. Via

[Image: An aerial view of Ground Zero, taken on September 23, 2001, by NOAA’s Cessna Citation Jet. Via  [Image: An example of origami tesselation, turning surface to structure, called “

[Image: An example of origami tesselation, turning surface to structure, called “ He refers to burning oil and coal as a way of “tapping the

He refers to burning oil and coal as a way of “tapping the  [Image: A glimpse of the Carboniferous Formation, or coal awaiting its own secular ascension;

[Image: A glimpse of the Carboniferous Formation, or coal awaiting its own secular ascension;  [Image: Coal – before being “loaded into the air” through burning].

[Image: Coal – before being “loaded into the air” through burning]. Looked at this way, it should come as no surprise that the Earth’s climate is now changing.

Looked at this way, it should come as no surprise that the Earth’s climate is now changing.