[Note: This is a guest post by Jim Rossignol].

Game developers are unconstrained in their designs for the enemy. Such designers will be punished with poor sales, not death in the gulag, if their designs for the overlord are unpopular. They could go anywhere with the homes of evildoers: halls of electric fluorescence, palaces carved from corduroy, suburban back yards.

And yet, in spite of this freedom, most videogame designers choose to make a definite connection to familiar – or real-world – architecture. Perhaps they think that the evil lair must emanate evil. There’s surely no room for ambiguity with videogame evildoers: the gamer needs to know that it’s okay to aim for hi-score vengeance.

[Image: From World of Warcraft].

[Image: From World of Warcraft].

Conveniently, evil already has a visual language. Put another way: I have seen the face of evil, and it is a caricature of gothic construction. There’s barely a necromancer in existence whose dark citadel doesn’t in some way reflect real-world Romanian landmarks, such as Hunyad or Bran Castle. The visual theme of these games is so heavily dependent on previously pillaged artistic ideas from Dungeons & Dragons and Tolkien that evil ambiance is delivered by shorthand. (Of course, World of Warcraft‘s Lich King gets a Stone UFO to fly around in – but it’s still the same old prefab pseudo-Medieval schtick inside). Where the enemy is extra-terrestrial, HR Giger‘s influence is probably going to be felt instead.

[Images: (top) Bran Castle, (bottom) Hunyad Castle, all via Wikipedia].

[Images: (top) Bran Castle, (bottom) Hunyad Castle, all via Wikipedia].

But, I suspect, these signposts – or the ways in which game designers architecturally represent evil – are becoming too much a part of our everyday imaginative discourse to remain affecting. They’ve begun to lose their danger. The connection with the inhumanity that makes the enemy so thrilling has started to fade via over-familiarity.

Where the evil lair becomes a little more interesting is when its nature is ambiguous – but nevertheless disturbing. Half-Life 2‘s Citadel is an example of this. The brutal gunmetal skyscraper that looms over a nameless Eastern European city, below, appears deeply threatening. But, like everything else in the Half-Life 2 universe, it is unexplained. It does not seem inherently evil. The structure moves and groans; it is a machine of some kind. It is something constructed and mechanical, rather than the clear manifestation or emanation of an evil force. The Citadel is not a fire-rimmed portal to hell, nor a windswept ruin. Nor is it a volcano base. It could even be somehow utilitarian. In fact, it’s reminiscent of the real Moscow’s own television tower.

It is, perhaps, even incidental to the scourge that Half-Life‘s denizens face: alien infrastructure. It is only later, as the plot uncoils the inner architecture of the Citadel, that you come to realise that it is the enemy: the lair of an alien force that must, ultimately, be destroyed.

[Image: From Half-Life 2].

[Image: From Half-Life 2].

Where the lair is itself the enemy, games are able to excel.

This is the case in both System Shock and System Shock 2, the finest of SF horror games. Both are set aboard spacecraft, but these spacecraft are also the “bodies” of the enemy: SHODAN, a malevolent Artificial Intelligence that controls each vessel.

In a provocative climax of virtuality-within-virtuality, the final act of System Shock 2 is to enter into the cyberspace realm of the AI and defeat SHODAN inside the graphical representation of her own programming. The evil lair is within the mind of the enemy – a motif repeated even more literally in Psychonauts, a game about exploring the physically manifested psyches of various bizarre characters.

[Image: From System Shock 2].

[Image: From System Shock 2].

More interesting visually, and far more ambiguous in its delivery of the evil lair, is the underwater city of Rapture, in Bioshock. The designers of this game (some of whom also worked on the System Shock series) poured the early part of the twentieth century into their designs, creating opulent, decaying, Art Deco corridors down which the genetically-enhanced super-human player goes thundering, searching for the enemy.

The ostentation of the city’s innards suggests that the city’s objectivist overseer, Andrew Ryan, must be the enemy we seek. He has, after all, created himself an entire city with a single, over-arching theme: a trademark act of the all-powerful videogame nemesis. Yet, as the story unfolds, it becomes clear that, although you will inevitably kill Ryan, his architecture tells you nothing about the nature of the enemy you face. Indeed, the true enemy has nothing to do with the stylised nature of this lair at all.

[Image: Channeling Ayn Rand, Andrew Ryan’s city banner announces “No Gods or Kings. Only Man.” From Bioshock].

[Image: Channeling Ayn Rand, Andrew Ryan’s city banner announces “No Gods or Kings. Only Man.” From Bioshock].

But perhaps the most extraordinary and unearthly of evil videogame architectures are the wandering colossi of Shadow of the Colossus. Great, living structures, lonely behemoths, that stride magnificently across the game world. These sad, shaggy giants of stone and moss must be climbed and slain by the hero, often via use of the surrounding environment of ancient ruins and meticulously designed geological formations. Lairs within lairs.

[Image: From Shadow of the Colossus].

[Image: From Shadow of the Colossus].

Of course, monsters are presumably evil, but the reality of the colossi remains ambiguous for much of the game. When the game is up, the player-character suffers a terrible price for destroying these strange, animate monuments. It is one of the few videogames in which the protagonist dies – horribly and permanently – when the game is over. It is a game where destroying the evil lair might well have been the wrong thing to do. And yet it is all you can do.

Such is the inexorable, linear fate of the videogame avatar.

[Jim Rossignol is a games critic for Offworld, an editor at Rock, Paper, Shotgun, and the author of the fantastic This Gaming Life: Travels in Three Cities. A full-length interview with Rossignol will appear on BLDGBLOG next week].

[Image: The epicenter: 3300 W. 112th Street].

[Image: The epicenter: 3300 W. 112th Street]. [Image: The

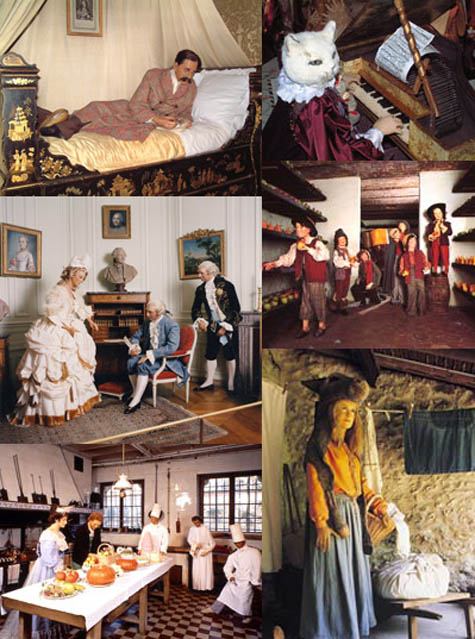

[Image: The  [Image: The wax stand-ins of

[Image: The wax stand-ins of  [Image: Puss in Boots stands before the

[Image: Puss in Boots stands before the  [Image: A

[Image: A  [Image: The semi-suburban origins of a seismic event].

[Image: The semi-suburban origins of a seismic event]. [Image: The Berlin

[Image: The Berlin  [Image: Hitler’s office in the

[Image: Hitler’s office in the  [Image: From

[Image: From

[Images: (top)

[Images: (top)  [Image: From

[Image: From  [Image: From

[Image: From  [Image: Channeling Ayn Rand, Andrew Ryan’s city banner announces “No Gods or Kings. Only Man.” From

[Image: Channeling Ayn Rand, Andrew Ryan’s city banner announces “No Gods or Kings. Only Man.” From  [Image: From

[Image: From  [Image:

[Image:  [Image: A stunning and very nearly unbelievable glimpse of

[Image: A stunning and very nearly unbelievable glimpse of  [Image: Youth storm a building; photo by

[Image: Youth storm a building; photo by  [Image: The

[Image: The  [Image: A

[Image: A  [Image: The astonishingly far inland dune-sea at 16th Avenue and

[Image: The astonishingly far inland dune-sea at 16th Avenue and