My friend Robert and I finished reading Alan Weisman’s The World Without Us almost simultaneously – and we both noted one specific passage.

Before we get to that, however, the premise of Weisman’s book – though it does, more often than not, drift away from this otherwise fascinating central narrative – is: what would happen to the Earth if humans disappeared overnight? What would humans leave behind, and how long would those remnants last?

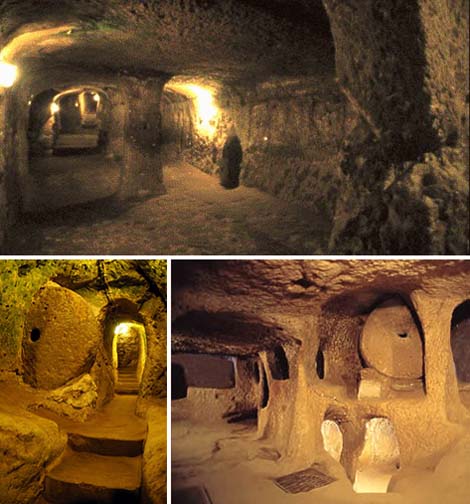

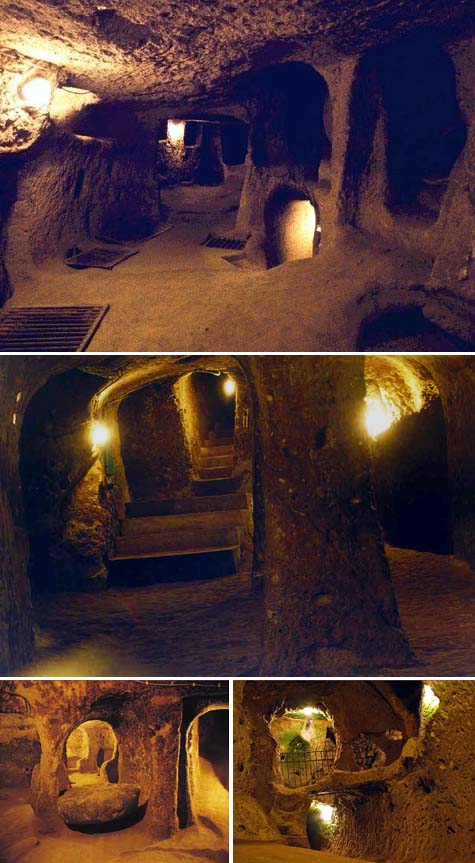

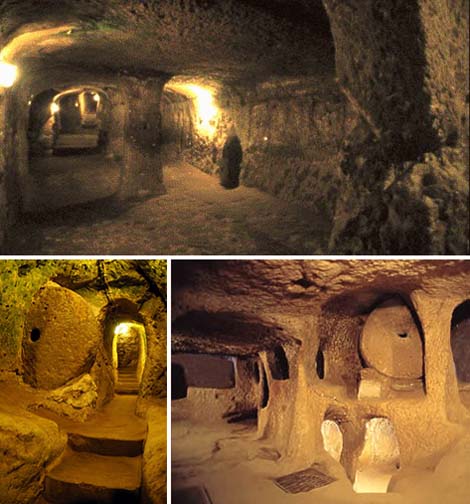

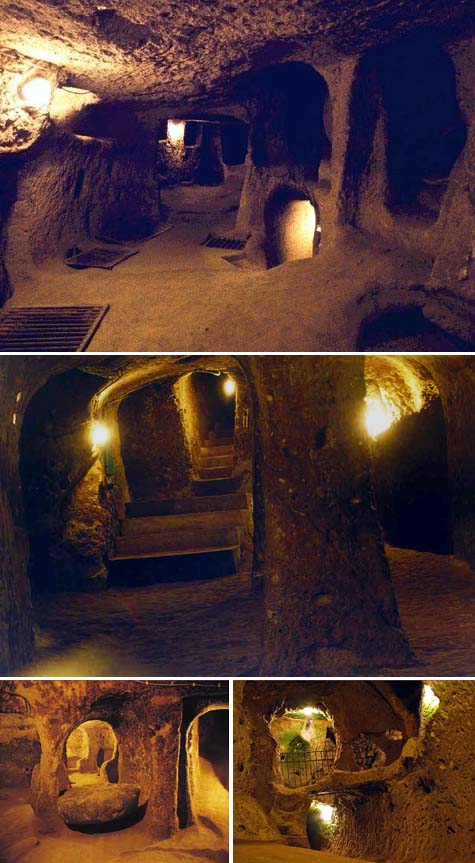

These questions lead Weisman at one point to discuss the underground cities of Cappadocia, Turkey, which, he says, will outlast nearly everything else humans have constructed here on Earth.

[Images: Derinkuyu, the great underground city of Cappadocia; images culled from a Google Images search and from Wikipedia].

[Images: Derinkuyu, the great underground city of Cappadocia; images culled from a Google Images search and from Wikipedia].

Manhattan will be gone, Los Angeles gone, Cape Canaveral flooded and covered with seaweed, London dissolving into post-Britannic muck, the Great Wall of China merely an undetectable line of minerals blowing across an abandoned landscape – but there, beneath the porous surface of Turkey, carved directly into tuff, there will still be underground cities.

[Images: Derinkuyu, the great underground city of Cappadocia; images culled from a Google Images search and from Wikipedia].

[Images: Derinkuyu, the great underground city of Cappadocia; images culled from a Google Images search and from Wikipedia].

Of course, I’m not entirely convinced by Weisman’s argument here – not that I have expertise in the field – but Turkey is a very seismically active country, for instance, and… it just doesn’t seem likely that these cities will be the last human traces to remain. But that’s something for another conversation.

In any case, Weisman writes:

No one knows how many underground cities lie beneath Cappadocia. Eight have been discovered, and many smaller villages, but there are doubtless more. The biggest, Derinkuyu, wasn’t discovered until 1965, when a resident cleaning the back wall of his cave house broke through a wall and discovered behind it a room that he’d never seen, which led to still another, and another. Eventually, spelunking archeologists found a maze of connecting chambers that descended at least 18 stories and 280 feet beneath the surface, ample enough to hold 30,000 people – and much remains to be excavated. One tunnel, wide enough for three people walking abreast, connects to another underground town six miles away. Other passages suggest that at one time all of Cappadocia, above and below the ground, was linked by a hidden network. Many still use the tunnels of this ancient subway as cellar storerooms.

I was excited to learn, meanwhile, that another – quite possibly larger – underground Cappadocian city, called Gaziemir, was only opened to tourists this summer (someone send me, please!), having been discovered in January 2007 (a discovery which doesn’t seem to have made the news outside Turkey).

So the next time the ground you’re walking on sounds hollow – perhaps it is… Whole new cities beneath our feet!

I was also excited to read, meanwhile, that these subsurface urban structures are acoustically sophisticated. In other words, Weisman writes, using “vertical communication shafts, it was possible to speak to another person on any level” down below. It’s a kind of geological party line, or terrestrial resonating gourd.

There were even ancient microbreweries down there, “equipped with tuff fermentation vats and basalt grinding wheels.”

[Images: Derinkuyu and a view of Cappadocia; images culled from a Google Images search and from Wikipedia].

[Images: Derinkuyu and a view of Cappadocia; images culled from a Google Images search and from Wikipedia].

Meanwhile, Robert, my co-reader of Weisman’s book, pointed out that the discovery of Derinkuyu, by a man who simply “broke through a wall and discovered behind it a room that he’d never seen, which led to still another, and another,” is surely the ultimate undiscovered room fantasy – and I have to agree.

However, it also reminded me of a scene from Foucault’s Pendulum – which is overwhelmingly my favorite novel (something I say with somewhat embarrassed hesitation because no one I have ever recommended it to – literally no one – not a single person! – has enjoyed, or even finished reading, it) – where we read about a French town called Provins.

In the novel, a deluded ex-colonel from the Italian military explains to two academic publishers that “something” has been in Provins “since prehistoric times: tunnels. A network of tunnels – real catacombs – extends beneath the hill.”

The man continues:

Some tunnels lead from building to building. You can enter a granary or a warehouse and come out in a church. Some tunnels are constructed with columns and vaulted ceilings. Even today, every house in the upper city still has a cellar with ogival vaults – there must be more than a hundred of them. And every cellar has an entrance to a tunnel.

The editors to whom this story has been told call the colonel out on this, pressing for more details, looking for evidence of what he claims. But the colonel parries – and then forges on. After all, he’s an ex-Fascist.

He’ll say what he likes.

As the colonel goes on, his story gets stranger: in 1894, he says, two Chevaliers went to visit an old granary in Provins, where they asked to be taken down into the tunnels.

Accompanied by the caretaker, they went down into one of the subterranean rooms, on the second level belowground. When the caretaker, trying to show that there were other levels even farther down, stamped on the earth, they heard echoes and reverberations. [The Chevaliers] promptly fetched lanterns and ropes and went into the unknown tunnels like boys down a mine, pulling themselves forward on their elbows, crawling through mysterious passages. [They soon] came to a great hall with a fine fireplace and a dry well in the center. They tied a stone to a rope, lowered it, and found that the well was eleven meters deep. They went back a week later with stronger ropes, and two companions lowered [one of the Chevaliers] into the well, where he discovered a big room with stone walls, ten meters square and five meters high. The others then followed him down.

So a few quick points:

1) Today’s city planners need to read more things like this! How exciting would it be if you could visit your grandparents in some small town somewhere, only to find that a door in the basement, which you thought led to a closet… actually opens up onto an underground Home Depot? Or a chapel. Or their neighbor’s house.

2) Do humans no longer build interesting subterranean structures like this – with the exception of militaries, where, to paraphrase Jonathan Glancey, we still see the architectural imagination at full flight – and I’m referring here to things like Yucca Mountain, something that would surely be too ambitious for almost any architectural design studio today – because they lack the imagination, or because of insurance liability? Is it possible that architectural critics today are lambasting the wrong people? It’s not that Daniel Libeskind or Peter Eisenman or Frank Gehry are boring, it’s simply that they’ve been hemmed in by unimaginative insurance regulations… Is insurance to blame for the state of contemporary architecture?

And if you called up State Farm to insure an underground city… what would happen?

Or if you tried to get UPS to deliver a package there?

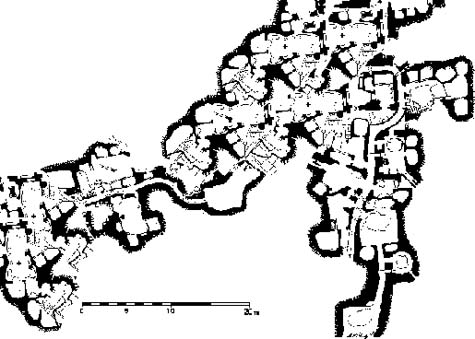

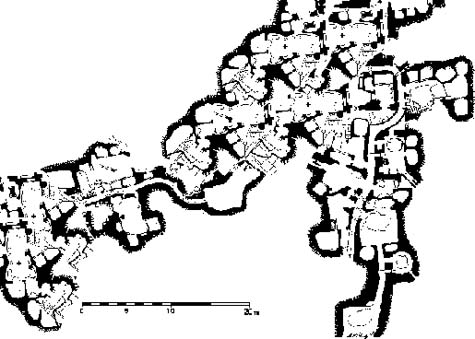

[Image: A map, altered by BLDGBLOG, of an underground Cappadocian metropolis].

[Image: A map, altered by BLDGBLOG, of an underground Cappadocian metropolis].

In any case, underground cities are far too broad and popular an idea to cover in one post – there’s even a Stephen King story about a maze of tunnels discovered beneath some kind of garment factory in Maine, where cleaners find a new, monstrous species of rat – and I’ve written about these subterranean worlds before. For instance, in Tokyo Secret City and in London Topological.

While I’m on the subject, then, London seems actually to be constructed more on re-buttressed volumes of air than it is on solid ground.

As Antony Clayton writes in his Subterranean City: Beneath the Streets of London:

The heart of modern London contains a vast clandestine underworld of tunnels, telephone exchanges, nuclear bunkers and control centres… [s]ome of which are well documented, but the existence of others can be surmised only from careful scrutiny of government reports and accounts and occassional accidental disclosures reported in the news media.

Meanwhile, I can’t stop thinking about the fact that some of the underground cities in Cappadocia have not been fully explored. I also can’t help but wonder if more than two thousand years’ worth of earthquakes might not have collapsed some passages, or even shifted whole subcity systems, so that they are no longer accessible – and, thus, no longer known.

Could some building engineer one day shovel through the Earth’s surface and find a brand new underground city – or might not some archaeologist, scanning the hills with ground-penetrating radar, stumble upon an anomalous void, linked to other voids, and the voids lead to more voids, and he’s discovered yet another long-lost city?

It’s also worth pointing out, quickly, that there is a Jean Reno film, called Empire of the Wolves, that is at least partially set inside a subsurface Cappadocian complex. What’s interesting about this otherwise uninteresting film is that it uses the carved heads and statuary of Cappadocia not at all unlike the way Alfred Hitchcock used Mount Rushmore in his film North by Northwest: the final action scenes of both films take place literally on the face of the Earth.

In any case, I should be returning to the topic of underground cities quite soon.

Books cited:

• Alan Weisman, The World Without Us

• Umberto Eco, Foucault’s Pendulum

• Anthony Clayton, Subterranean City: Beneath the Streets of London

(With huge thanks to Robert Krulwich for kicking off this post!)

[Image: From 2001: A Space Odyssey].

[Image: From 2001: A Space Odyssey]. [Images: Derinkuyu, the great underground city of Cappadocia; images culled from a

[Images: Derinkuyu, the great underground city of Cappadocia; images culled from a  [Images: Derinkuyu, the great underground city of Cappadocia; images culled from a

[Images: Derinkuyu, the great underground city of Cappadocia; images culled from a  [Images: Derinkuyu and a view of Cappadocia; images culled from a

[Images: Derinkuyu and a view of Cappadocia; images culled from a  [Image: A map, altered by BLDGBLOG, of an underground Cappadocian metropolis].

[Image: A map, altered by BLDGBLOG, of an underground Cappadocian metropolis].