As published by Science and Mechanics in November 1931, the depthscraper was proposed as a residential engineering solution for surviving earthquakes in Japan.

As published by Science and Mechanics in November 1931, the depthscraper was proposed as a residential engineering solution for surviving earthquakes in Japan.

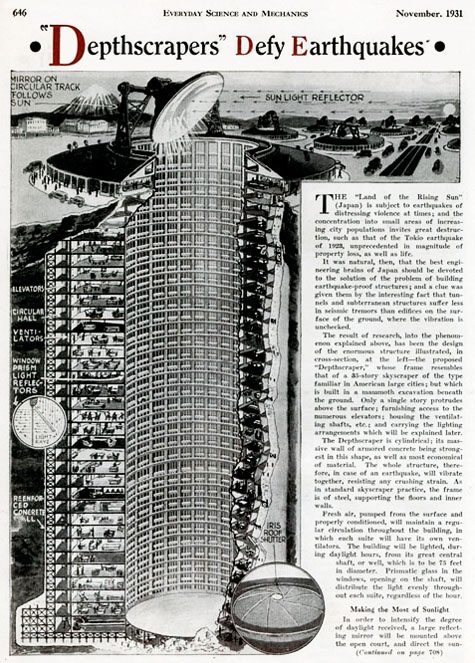

The subterranean building, “whose frame resembles that of a 35-story skyscraper of the type familiar in American large cities,” would actually be constructed “in a mammoth excavation beneath the ground.”

Only a single story protrudes above the surface; furnishing access to the numerous elevators; housing the ventilating shafts, etc.; and carrying the lighting arrangements… The Depthscraper is cylindrical; its massive wall of armored concrete being strongest in this shape, as well as most economical of material. The whole structure, therefore, in case of an earthquake, will vibrate together, resisting any crushing strain. As in standard skyscraper practice, the frame is of steel, supporting the floors and inner walls.

My first observation here is actually how weird the punctuational style of that paragraph is. Why all the commas and semicolons?

My second thought is that this thing combines about a million different themes that interest me: underground engineering, seismic activity, redistributed sunlight through complicated systems of mirrors, architectural speculation, disastrous social planning, etc. etc.

In J.G. Ballard’s hilariously excessive 1975 novel High-Rise – one of the most exciting books of architectural theory, I’d suggest, published in the last fifty years – we read about the rapid descent into chaos that befalls a brand new high-rise in London. Ballard writes that “people in high-rises tend not to care about tenants more than two floors below them.” Indeed, the very design of the building “played into the hands of the most petty impulses” – till “deep-rooted antagonisms,” assisted by chronic middle-class sexual boredom and insomnia, “were breaking through the surface of life within the high-life at more and more points.”

The residents are doomed: “Like a huge and aggressive malefactor, the high-rise was determined to inflict every conceivable hostility upon them.” One of the characters even “referred to the high-rise as if it were some kind of huge animate presence , brooding over them and keeping a magisterial eye on the events taking place.”

My point is simply that it doesn’t take very much to re-imagine Ballard’s novel set in a depthscraper: what strange antagonisms might break out in a buried high-rise?

Living underground, then, could perhaps be interpreted as a kind of avant-garde psychological experiment – experiential gonzo psychiatry.

I’m reminded here of the bunker psychology explored by Tom Vanderbilt in his excellent book Survival City: Adventures Among the Ruins of Atomic America.

In the midst of a long, and fascinating, tour through the 20th century’s wartime underworlds, Vanderbilt writes of how “the confined underground space becomes a concentrated breeding ground for social dysfunction as the once-submerged id rages unchecked.” Living inside “massive underground fortifications” – whether fortified against enemy attack or against spontaneous movements of the earth’s surface – might even produce new psychiatric conditions, Vanderbilt writes. There were rumors of “‘concretitis’ and other strange new ‘bunker’ maladies” breaking out amidst certain military units garrisoned underground.

What future psychologies might exist, then, in these depthscrapers built along active faultlines?