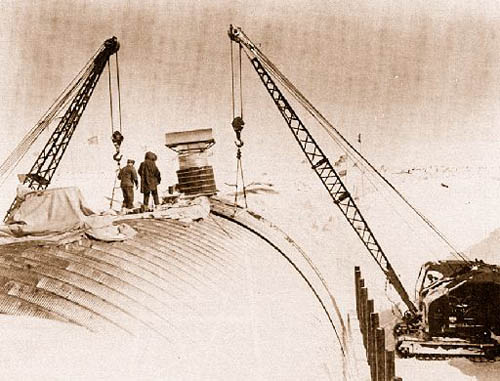

[Image: Camp Century under construction; photograph via Frank J. Leskovitz].

[Image: Camp Century under construction; photograph via Frank J. Leskovitz].

Camp Century—aka “Project Iceworm”—was a “city under ice,” according to the U.S. Army, a “nuclear-powered research center built by the Army Corps of Engineers under the icy surface of Greenland,” as Frank J. Leskovitz explains.

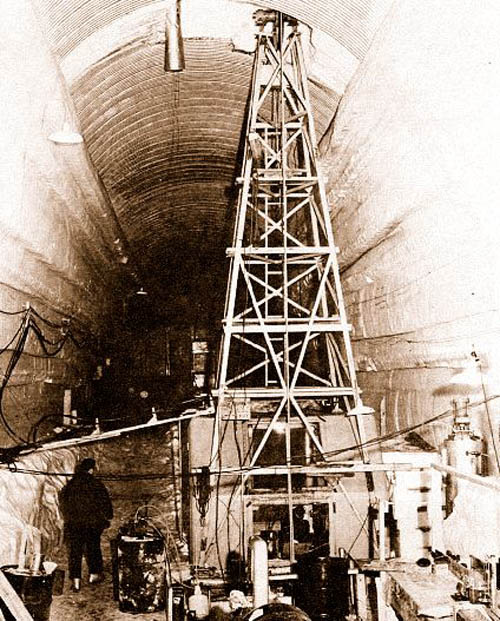

A fully-functioning underground city, Camp Century even had its own mobile nuclear reactor—an “Alco PM-2A”—that kept the whole thing lit up and running during the Cold War.

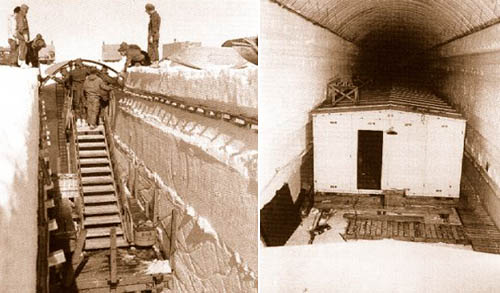

[Images: Camp Century under construction; photographs via Frank J. Leskovitz].

[Images: Camp Century under construction; photographs via Frank J. Leskovitz].

According to Leskovitz, the Camp’s construction crews “utilized a ‘cut-and-cover’ trenching technique” during the base’s infra-glacial assembly:

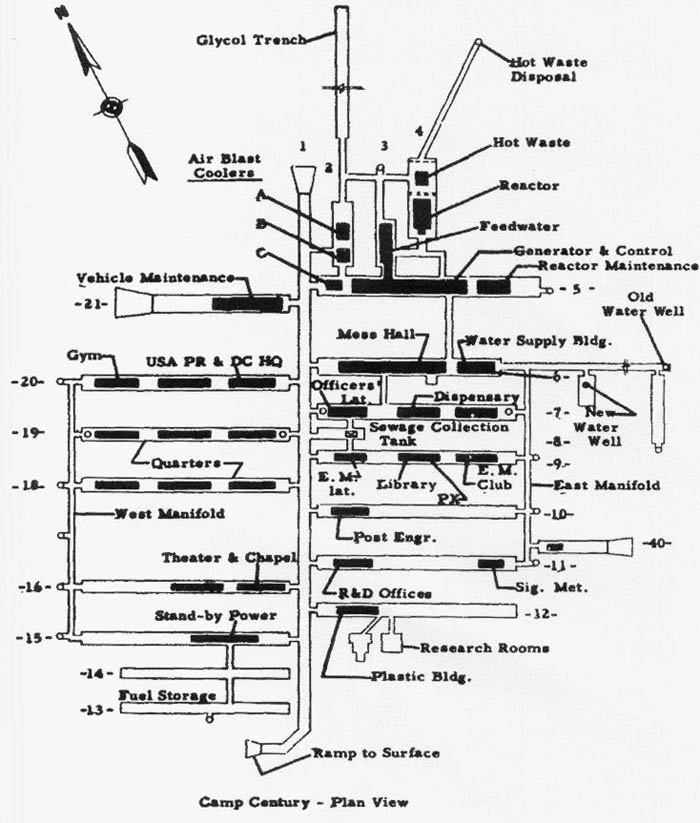

Long ice trenches were created by Swiss made “Peter Plows,” which were giant rotary snow milling machines. The machine’s two operators could move up to 1200 cubic yards of snow per hour. The longest of the twenty-one trenches was known as “Main Street.” It was over 1100 feet long and 26 feet wide and 28 feet high. The trenches were covered with arched corrugated steel roofs which were then buried with snow.

Prefab facilities were then added, with “wood work buildings and living quarters… erected in the resulting snow tunnels.”

[Images: Camp Century under construction; photographs via Frank J. Leskovitz].

[Images: Camp Century under construction; photographs via Frank J. Leskovitz].

Leskowitz continues:

Each seventy-six foot long electrically heated barrack contained a common area and five 156 square foot rooms. Several feet of airspace was maintained around each building to minimize melting. To further reduce heat build-up, fourteen inch diameter “air wells” were dug forty feet down into the tunnel floors to introduce cooler air. Nearly constant trimming of the tunnel walls and roofs was found to be necessary to combat snow deformation.

Camp Century went from a scientific outpost to a potential U.S. Army site for hosting battle-ready nuclear missiles underneath the Greenland ice sheet—the so-called “Project Iceworm” mentioned earlier.

The following four short videos, produced by the U.S. military, explore the site’s strange technical circumstances as well as its complicated defensive history.

“During this period of the Cold War,” Leskovitz explains, “the U.S. Army was working on plans to base newly designed ‘Iceman’ ICBM missiles in a massive network of tunnels dug into the Greenland icecap. The Iceworm plans were eventually deemed impractical and abandoned,” and, “due to unanticipated movement of the glacial ice,” the entire subterranean complex was eventually left in ruins.

The idea that the moving terrain of a glacial ice sheet could be considered a stable-enough launching point for nuclear missiles is astonishing, and the idea that the U.S. Army once ran a top secret—and rather Metallica-sounding—”city under ice” just shy of the North Pole only adds to the story’s disarming surreality.

[Image: The plan of Camp Century; via Frank J. Leskovitz].

[Image: The plan of Camp Century; via Frank J. Leskovitz].

In any case, more photographs, including of the Army’s mobile nuclear reactor, are available on Leskovitz’s own site.

*Update* In August 2016, a study published in the journal Geophysical Research Letters suggested that “climate change could remobilize abandoned hazardous waste thought to be buried forever beneath the Greenland Ice Sheet,” specifically referring to the ruins of Camp Century.

“Camp Century could start to melt by the end of the century,” the American Geophysical Union summarizes. “If the ice melts, the camp’s infrastructure, as well as any remaining biological, chemical and radioactive waste, could re-enter the environment and potentially disrupt nearby ecosystems.”

[Image: U.S. Army photograph, via the American Geophysical Union].

[Image: U.S. Army photograph, via the American Geophysical Union].

Here is a PDF of the complete paper.