[Image: Peder Balke, “Seascape” (1848), courtesy of the Athenaeum].

[Image: Peder Balke, “Seascape” (1848), courtesy of the Athenaeum].

As cities like New York prepare for “permanent flooding,” and as we remember submerged historical landscapes such as Doggerland, lost beneath the waves of a rising North Sea, it’s interesting to read that humanity’s ancient past—not just its looming future—might be fundamentally maritime, rather than landlocked. Or oceanic rather than terrestrial, we might say.

In his recent book The Human Shore, historian John R. Gillis suggests that, due to a variety of factors, including often extreme transportation difficulties presented by inland terrain, traveling by sea was the obvious choice for early human migrants.

People, after all, have been seafaring for at least 130,000 years.

This focus on seas and waterways came with political implications, Gillis writes. Even when European merchant-explorers reached North America, “It would be a very long time, almost three hundred years, before Europeans realized the full extent of the Americas’ continental character and grasped the fact that they might have to abandon the ways of seaborne empires for those of territorial states.” In fact, he adds, “for the first century or more, northern Europeans showed more interest in navigational rights to certain waterways and sea tenures than in territorial possession as such.”

At the risk of anachronism, you might say that their power was defined by logistical concerns, rather than by territorial ones: by dynamic, just-in-time access to ports and routes, rather than by the stationary establishment of landed borders and policed frontiers.

[Image: “Ship in a Storm” (ca. 1826), by Joseph Mallord William Turner; courtesy Tate Britain].

[Image: “Ship in a Storm” (ca. 1826), by Joseph Mallord William Turner; courtesy Tate Britain].

Gillis goes much further than this, however, suggesting that—as 130,000 years of seafaring history seems to indicate—humans simply are not a landlocked species.

“Even today,” Gillis claims, “we barely acknowledge the 95 percent of human history that took place before the rise of agricultural civilization.” That is, 95 percent of human history spent migrating both over land and over water, including the use of early but sophisticated means of marine transportation that proved resistant to archaeological preservation. For every lost village or forgotten house, rediscovered beneath a quiet meadow, there are a thousand ancient shipwrecks we don’t even know we should be looking for.

Perhaps speaking only for myself, this is where things get particularly interesting. Gillis points out that humanity’s deep maritime history has been almost entirely written out of our myths and religions.

In his words, “the book of Genesis would have us believe that our beginnings were wholly landlocked, but it was written at the time that the Hebrews were settling down to an agrarian existence.” That is, the myth of Genesis was written from the point of view of a culture already turning away from the sea, mastering animal domestication, mining, and wheeled transport, and settling down away from the coastline. It was learning to cultivate gardens: “The story of Eden served admirably as the foundational myth for agricultural society,” Gillis writes, but it performs very poorly when seen in the context of humanity’s seagoing past.

Briefly, I have to wonder what might have happened had works of literature—or, more realistically, highly developed oral traditions—from this earlier era been better preserved. Seen this way, The Odyssey would merely be one, comparatively recent example of seafaring mythology, and from only one maritime culture. But what strange, aquatic world of gods and monsters might we still be in thrall of today had these pre-Edenic myths been preserved—as if, before the Bible, there had been some sprawling Lovecraftian world of coral reefs, lost ships, and distant archipelagoes, from the Mediterranean to Southeast Asia?

[Image: “Storm at Sea” (ca. 1824), by Joseph Mallord William Turner; courtesy Tate Britain].

[Image: “Storm at Sea” (ca. 1824), by Joseph Mallord William Turner; courtesy Tate Britain].

This is where this post’s title comes from. “In short,” Gillis concludes, “we require a new narrative, one with, as Steve Mentz suggests, ‘fewer gardens, and more shipwrecks.’”

Fewer gardens, more shipwrecks. We are more likely, Gillis and Mentz imply, to be the outcast descendants of sunken ships and abandoned expeditions than we are the landed heirs of well-tended garden plots.

Seen this way, even if only for the purpose of a thought experiment, human history becomes a story of the storm, the wreck, the crash—the distant island, the unseen reef, the undertow—not the farm or even the garden, which would come to resemble merely a temporary domestic twist in this much more ancient human engagement with the sea.

[Image: The Great Lakes are draining; photo by James Rajotte for

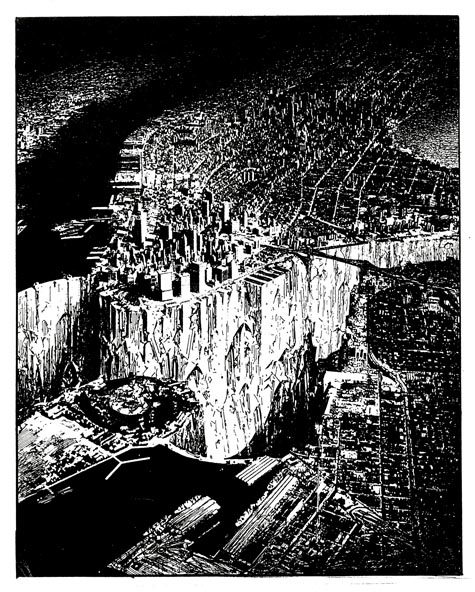

[Image: The Great Lakes are draining; photo by James Rajotte for  [Image: Lebbeus Woods, Lower Manhattan; view

[Image: Lebbeus Woods, Lower Manhattan; view  [Image: Simon Norfolk, a photographer previously

[Image: Simon Norfolk, a photographer previously  But who knows – perhaps 2008 is the year N.A.W.A.P.A. makes a comeback. Or, perhaps, in January 2010, after another dry winter, Los Angeles voters will start to get thirsty. Perhaps some well-positioned Senators, in 2011, might even start making phonecalls north. Perhaps, in 2012, some recent graduates from water management programs at state-funded universities in Illinois or Utah might catch the itch of moral rebellion; they might then start redrawing their personal maps of the continent, going to bed at night with visions of massive dams in their heads, writing position papers for peer-reviewed hydrological engineering magazines.

But who knows – perhaps 2008 is the year N.A.W.A.P.A. makes a comeback. Or, perhaps, in January 2010, after another dry winter, Los Angeles voters will start to get thirsty. Perhaps some well-positioned Senators, in 2011, might even start making phonecalls north. Perhaps, in 2012, some recent graduates from water management programs at state-funded universities in Illinois or Utah might catch the itch of moral rebellion; they might then start redrawing their personal maps of the continent, going to bed at night with visions of massive dams in their heads, writing position papers for peer-reviewed hydrological engineering magazines.  [Image: A fish-cleaning station in Las Vegas Bay, now abandoned by the West’s sinking waters; taken by

[Image: A fish-cleaning station in Las Vegas Bay, now abandoned by the West’s sinking waters; taken by