Geologist Michael Welland has an interesting post up about the “first detailed examination of extra-terrestrial sand dunes” on Mars, coming later this year. His post also briefly discusses the life and career of Ralph Bagnold, after whom the Martian dunes are named, as well as the granular physics of a remote landscape that, in Welland’s words, “just seems, instinctively, to be unearthly.”

Tag: Michael Welland

War Sand

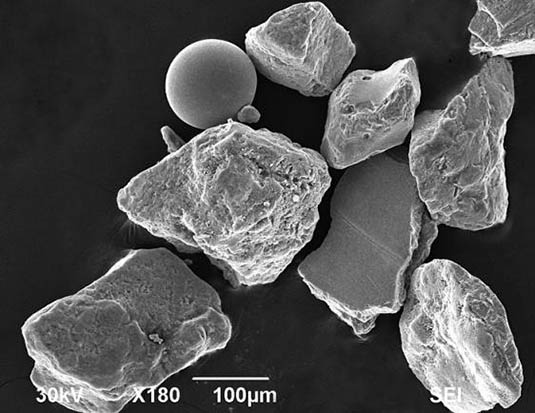

[Image: Geologist Earle McBride’s microscopic images of war sand on the beaches of Normandy].

[Image: Geologist Earle McBride’s microscopic images of war sand on the beaches of Normandy].

A short piece in the September/October 2012 issue of Archaeology magazine highlights the presence of spherical magnetic shards—remnants of the D-Day operations of World War II—found hidden amongst natural sand grains on the beaches of Normandy. “Up to 4 percent of the sand is made up of this shrapnel,” the article states; however, “waves, storms, and rust will probably wipe this microscopic archaeology from the coast in another hundred years.”

This is not a new discovery, of course. In Michael Welland’s book Sand, often cited here on BLDGBLOG, we read that, “on Normandy beaches where D-Day landings took place, you will find sand-sized fragments of steel”—an artificial landscape of eroded machines still detectable, albeit with specialty instruments, in the coastal dunes.

I’m reminded of a line from The Earth After Us: What Legacy Will Humans Leave in the Rocks?, a speculative look by geologist Jan Zalasiewicz at the remains of human civilization 100 million years from now. There, we read that “skyscrapers and semi-detached houses alike, roads and railway lines, will be reduced to sand and pebbles, and strewn as glistening and barely recognizable relics along the shoreline of the future.”

The oddly shaped magnetic remains of World War II are thus a good indication of how our cities might appear after humans have long departed.