[Image: Kurt, the Nazi weather station, via Beachcombing].

[Image: Kurt, the Nazi weather station, via Beachcombing].

My morning began with the fascinating story of Kurt, a forgotten Nazi weather station installed on the coast of Labrador during World War II that was only rediscovered in 1981. From a long article by Murray Sager:

Wetterfunkgerat Land 26 (code name “Kurt“) consisted of ten canisters, one for the recording instruments, another for the 10-metre antenna and the others for the world’s first Ni-cad batteries. There was a second mast for an anemometer and wind vane. These automatic stations were designed to broadcast temperature, wind speed and direction, air pressure and humidity in coded 120-second broadcasts every three hours and were designed to operate for six months. The Germans had also developed automatic weather buoys which were normally submerged but surfaced to record and broadcast before re-submerging. They had a designed “life” of nine months, and some were still operating into 1946. “Kurt” however had a short life, falling silent after only a couple of broadcasts. The Germans were unable to return to repair it or to place a planned second station on Labrador.

From here, it becomes something out of a Jules Verne novel:

The station’s existence might have remained unknown. However, the son of the meteorologist attached to the U-boat [that originally installed Kurt], while going through his lather’s papers after his death, found photographs of a barren rock and snow covered coastline that he could not identify. He contacted Franz Selinger, a retired Siemens engineer who was writing a history of the company (Siemens had built the automatic stations). The photos were tentatively identified and on a Canadian Coast Guard patrol along the coast of Labrador they were used to match the present day shoreline, and the remains of the station were found.

The blog post where I first read the story suggests that weather warfare would make for an amazing book—as it happens, much of James Fleming’s recent Fixing the Sky: The Checkered History of Weather and Climate Control is about exactly that.

In a fantastic paper called “The Climate Engineers,” for instance, originally published in the Wilson Quarterly, Fleming quotes General George C. Kenney, former head of the Allied Strategic Air Command: Kenney once declared that “the nation which first learns to plot the paths of air masses accurately and learns to control the time and place of precipitation will dominate the globe”—first-strike meteorology, perhaps. Fleming goes on to describe hallucinatory military visions of a “perfectly accurate machine forecast combined with a paramilitary rapid deployment force” that could annihilate all enemies—a Global Weather Corps, so to speak, flying ahead of the storm winds that it itself would generate.

In any case, read Beachcombing and Murray Sager for more about this abandoned Nazi weather station in the Allied Arctic.

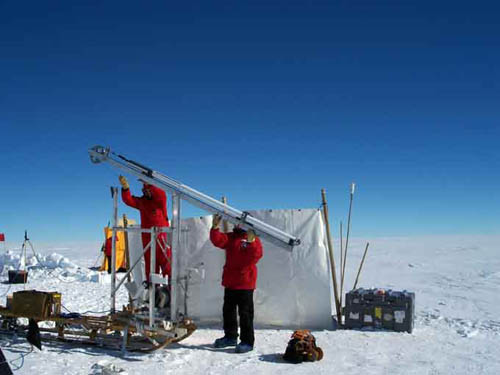

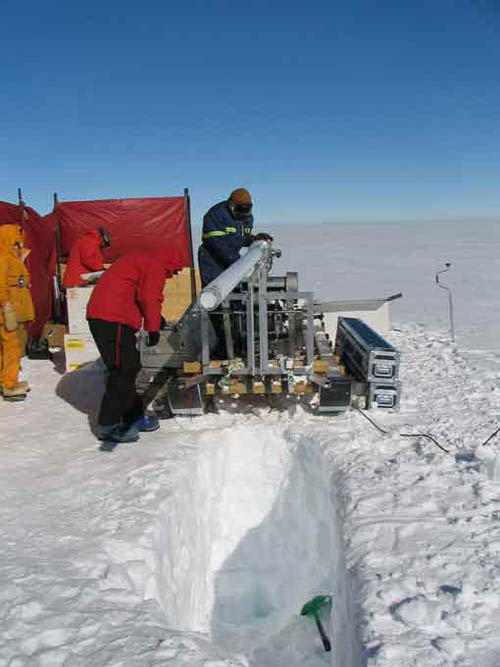

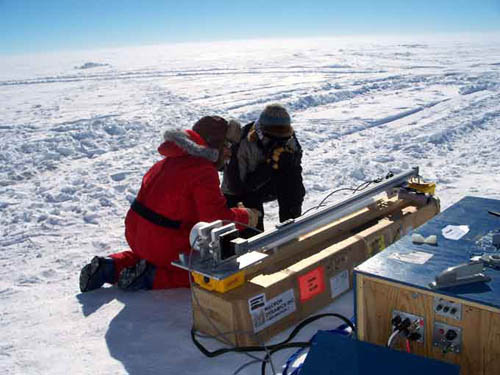

[Image: From the 2006-2007

[Image: From the 2006-2007  [Image: From the 2006-2007

[Image: From the 2006-2007

[Images: From the 2006-2007

[Images: From the 2006-2007  [Image: From the 2006-2007

[Image: From the 2006-2007  If you could design a bridge across the Bering Strait, connecting the U.S. to Russia, what would it look like? Come up with something good and you could win as much as $80,000 ($20,000, if you’re a student).

If you could design a bridge across the Bering Strait, connecting the U.S. to Russia, what would it look like? Come up with something good and you could win as much as $80,000 ($20,000, if you’re a student).