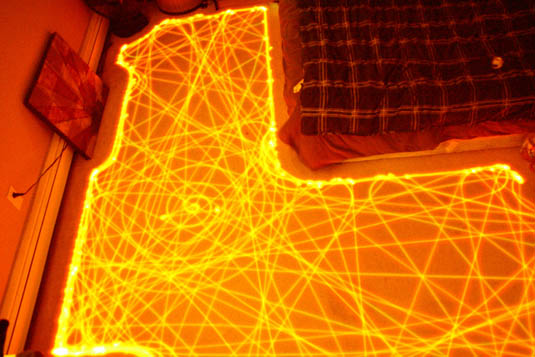

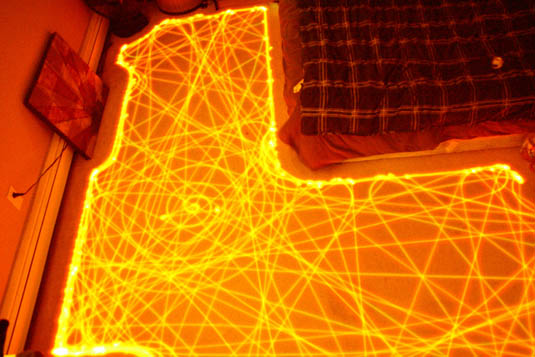

[Image: Optically tagged “robot-friendly bed sheets” from With Robots by Diego Trujillo-Pisanty].

[Image: Optically tagged “robot-friendly bed sheets” from With Robots by Diego Trujillo-Pisanty].

Diego Trujillo-Pisanty, currently a student in the Design Interactions department at the Royal College of Art in London, has looked ahead at how future homes might be redesigned to accommodate domestic robots.

Rather than build entire new forms of architecture, however, Diego suggests that we’ll first begin quite simply: retrofitting our interior environments, in often deceptively small ways, for optical navigation by autonomous mobile home systems. This will primarily take the form of peripheral additions to everyday objects, as well as a new range of optical tags that will allow certain tasks—folding blankets, for instance, or setting the dinner table—to be accomplished much easier by machines.

These tags will define both physical limits and the spatial operations appropriate within them, coding the everyday home environment for the rise of machine intelligence.

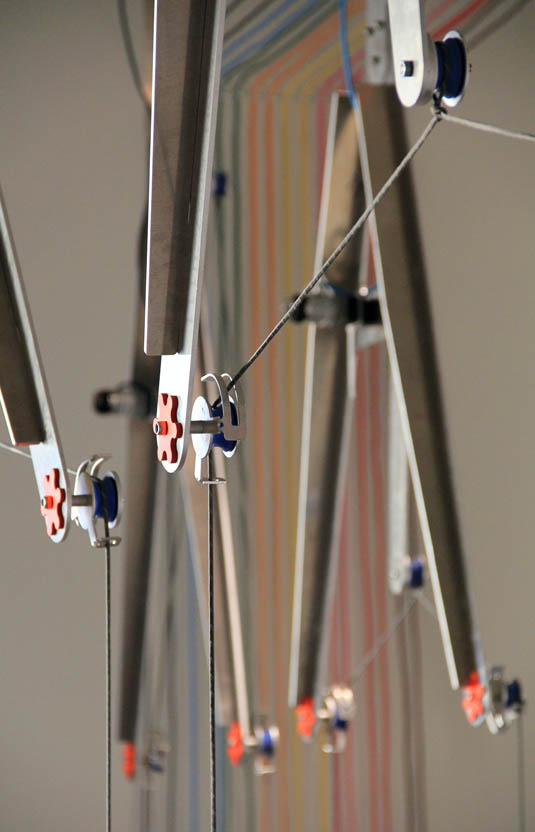

[Image: From With Robots by Diego Trujillo-Pisanty].

[Image: From With Robots by Diego Trujillo-Pisanty].

Homeowners will even help their robots learn through computational games—like Fröbel blocks for machines.

“Every living space is different,” the project description explains, “not only in the architectural layout, but also in the tasks that the tenants require robots to do. For this reason, robots ship only partially programmed so that through a learning algorithm they might adapt to the home they operate in. To accelerate the learning process, special learning tools have been designed to help the robot integrate to a 3D environment.” The photograph seen below “shows a living room after a robot self-training session. We can see it has now mastered the physics of equilibrium. It is also evident that it has mistaken one of the house’s dinner plates which it has broken with robotic precision to complete its piece.”

[Image: From With Robots by Diego Trujillo-Pisanty].

[Image: From With Robots by Diego Trujillo-Pisanty].

“Robot-friendly” handles will also be added to coffee mugs, the project suggests—which then ripples outward, effecting other spatial dimensions of the domestic environment, including where those mugs are stored. Thus, we read, “the cupboards in which these cups rest have also been altered in order to accommodate the robot. Not only are there tags marking the position of objects, but the doors have also been removed as they were not fit for A.I.”

[Image: From With Robots by Diego Trujillo-Pisanty].

[Image: From With Robots by Diego Trujillo-Pisanty].

Cooking itself will also be altered; the next image seen here “shows how meat has been precisely cut into cubes without leaving any cut marks on the chopping board. The board itself has notches to facilitate robot interaction. In the background the meat package can be seen; it too has been labelled to suggest that the robots operate beyond a single house.”

[Image: From With Robots by Diego Trujillo-Pisanty].

[Image: From With Robots by Diego Trujillo-Pisanty].

In a recent, highly recommended TED Talk, games designer Kevin Slavin discusses how the design of the physical world is being increasingly optimized for algorithms—and one of his central examples is the Roomba self-guided home vacuum cleaner.

[Image: A Roomba reveals its algorithms in this photo by Signal Theorist, via IEEE Spectrum].

[Image: A Roomba reveals its algorithms in this photo by Signal Theorist, via IEEE Spectrum].

The Roomba, in this context, becomes emblematic of the rise of a new kind of device, one with direct spatial and optical effects on the architecture inside of which it functions.

In fact, it is not difficult to imagine, as both Diego Trujillo-Pisanty’s and Kevin Slavin‘s work suggest, a world in which everyday furniture has been subtly redesigned in order to fit the Roomba’s spiraling subroutines—and not the other way around—or even whole rooms peppered with strange, ankle-high optical tags on certain walls, doors, or objects, used to steer the Roomba this way or that at specific points in its room-cleaning operations.

Like a tomb from Egypt’s Valley of the Kings, our houses will be covered in hieroglyphs—machine-hieroglyphs, not legible as much as they are optically recognizable.

Now scale this up to the size of, say, Wall-E, and you get With Robots: a spatial environment slightly, almost invisibly, somehow off, idealized not for human beings at all, but for the spatial needs of intelligent objects.

[Image: A mechanical cloud of A-frames from “Surface Tension” by Smout Allen].

[Image: A mechanical cloud of A-frames from “Surface Tension” by Smout Allen].  [Image: Landscape Futures, “to be enlarged a lot”].

[Image: Landscape Futures, “to be enlarged a lot”].

[Image: Optically tagged “robot-friendly bed sheets” from

[Image: Optically tagged “robot-friendly bed sheets” from  [Image: From

[Image: From  [Image: From

[Image: From  [Image: From

[Image: From  [Image: From

[Image: From  [Image: A

[Image: A

[Image: Photo by Brian Harkin for

[Image: Photo by Brian Harkin for  [Image: Promotional poster for the otherwise unrelated film

[Image: Promotional poster for the otherwise unrelated film

[Images: From

[Images: From

[Image: From The Gray Rush, a new work by

[Image: From The Gray Rush, a new work by

[Image: From

[Image: From  [Image: From

[Image: From

[Images: From

[Images: From

[Image: Photograph by Ben Behnke courtesy of

[Image: Photograph by Ben Behnke courtesy of  [Image: Diagram courtesy of

[Image: Diagram courtesy of

[Image: Photographs by Ben Behnke courtesy of

[Image: Photographs by Ben Behnke courtesy of  [Image: Reasons to be cheerful; photo by Ben Behnke, courtesy of

[Image: Reasons to be cheerful; photo by Ben Behnke, courtesy of

[Images: The

[Images: The  [Images: An installation shot from

[Images: An installation shot from

[Image: From

[Image: From  [Image: From

[Image: From

[Image: Artist

[Image: Artist  —Speaking of New York City, 30 July 2011 will see the widespread arrival of a new architectural typology: the

—Speaking of New York City, 30 July 2011 will see the widespread arrival of a new architectural typology: the  [Image: Mount Everest, via

[Image: Mount Everest, via  [Image: Painting by Andre Sokolov from

[Image: Painting by Andre Sokolov from

[Image: A still from

[Image: A still from  [Image: From

[Image: From