[Image: 10 Mile Spiral, “A Gateway to Las Vegas,” by Benjamin Aranda and Chris Lasch].

[Image: 10 Mile Spiral, “A Gateway to Las Vegas,” by Benjamin Aranda and Chris Lasch].

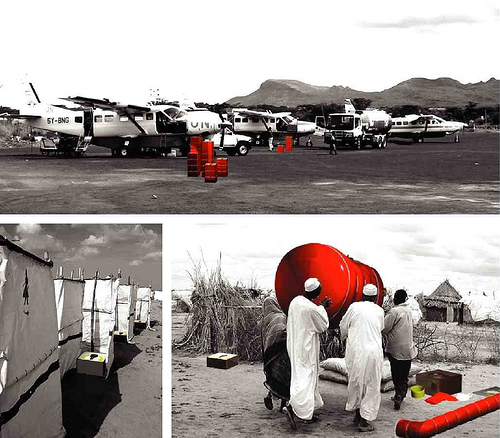

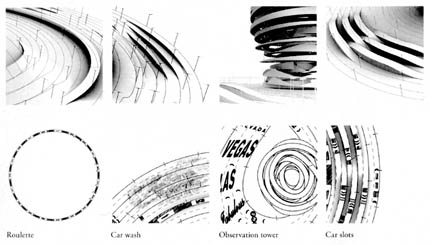

In their recent and immensely enjoyable book Tooling, New York-based architects Benjamin Aranda and Chris Lasch propose, among other things, a “10 mile spiral” that will “serve two civic purposes for Las Vegas”:

First, it acts as a massive traffic decongestion device… by adding significant mileage to the highway in the form of a spiral. The second purpose is less infrastructural and more cultural: along the spiral you can play slots, roulette, get married, see a show, have your car washed, and ride through a tunnel of love, all without ever leaving your car. It is a compact Vegas, enjoyed at 55 miles per hour and topped off by a towering observation ramp offering views of the entire valley floor below.

An aerial view of the spiral, in all its gas-guzzling glory, wound up like a snake on the periphery of the city:

[Image: Aranda/Lasch, from Tooling].

[Image: Aranda/Lasch, from Tooling].

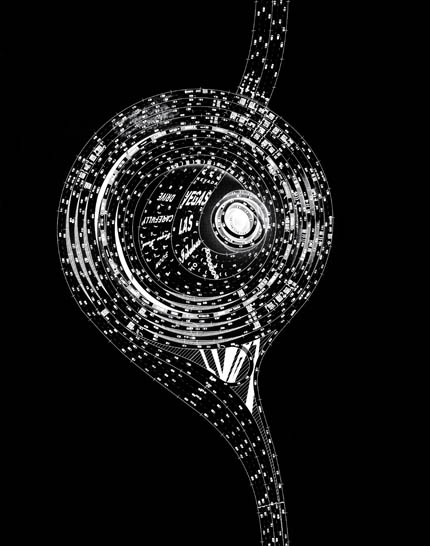

Drivers will enter this vertical labyrinth of concrete, approaching a whirligig-like compression of the desert horizon and gradually lifting off into the sky. It’s a kind of herniation of space through which you could theoretically drive forever. (Given enough gasoline).

The spiral itself is beautiful –

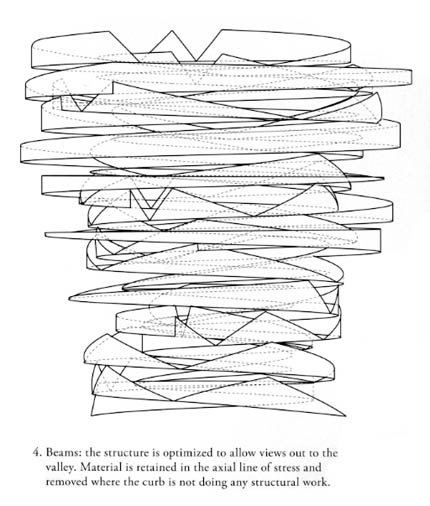

– and absurd. Its form was generated algorithmically as “a helix whose radius varies randomly as it climbs and then falls back down to the valley floor.” The structure’s “intersection points” are then located, acting as stress-sites “through which the structure’s loads are channeled to the ground.”

– and absurd. Its form was generated algorithmically as “a helix whose radius varies randomly as it climbs and then falls back down to the valley floor.” The structure’s “intersection points” are then located, acting as stress-sites “through which the structure’s loads are channeled to the ground.”

It’s an internally buttressed Futuro-Suprematist cathedral to cars.

[Image: Aranda/Lasch, from Tooling].

[Image: Aranda/Lasch, from Tooling].

At the end of the book, Aranda/Lasch note that every project featured in Tooling was “constructed through simple steps, repeated over and over until something of substance was revealed”:

These steps are usually straightforward geometric transformations – short sets of rules that we develop – sometimes to build a custom tool that had not yet existed, but more often to better understand the forms we wish to make. Tapping the number-crunching power of the computer opens up new design possibilities and gives us the capacity to grow and proliferate structures that we otherwise could not, but probably more important is deciding when to curb their growth, cut their shape, or stop using them altogether.

In this regard, their architectural projects have much more in common with, say, the calculation-dependent music of Autechre than with anything explicitly spatial – unless that space is the coiling inward voids of conch shells, perhaps, or the strangely mathematical scaffolding of radiolaria.

At some point, Aranda/Lasch add, all the algorithmic tools they themselves used will be made available to anyone else who wants to explore them; to see if that’s happened yet, check this website in a few months’ time.

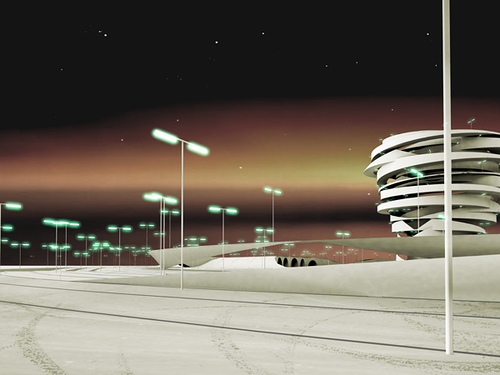

[Image: The spectacular glowing interior of that which has no outside: it’s the 10 Mile Spiral from above, at night, lit from within by automobiles. Aranda/Lasch, from Tooling].

[Image: The spectacular glowing interior of that which has no outside: it’s the 10 Mile Spiral from above, at night, lit from within by automobiles. Aranda/Lasch, from Tooling].

I can’t end this post, however, without quoting J.G. Ballard; it’s like a nervous tic, seeing so many roads – and out comes Concrete Island, Ballard’s now-classic novel about an architect trapped by a car crash in the “compulsory landscaping” of Greater London’s excess motorways: “In his aching head the concrete overpass and the system of motorways in which he was marooned had begun to assume an ever more threatening size. The illuminated route indicators rotated above his head, marked with meaningless destinations.”

The man falls prey to thirst, insomnia, delirium: “Gazing up at the maze of concrete causeways illuminated in the night air, he realized how much he loathed all these drivers and their vehicles.”

The man then searches for “some circuitous route through the labyrinth of motorways” – but finds none. He is trapped, a new Crusoe of roads, “alone in this forgotten world whose furthest shores were defined only by the roar of automobile engines… an alien planet abandoned by its inhabitants, a race of motorway builders who had long since vanished but had bequeathed to him this concrete wilderness.”

Leading me to wonder: what new futures of human experience could arise in the 10 Mile Spiral?

[Image: Aranda/Lasch, from Tooling].

[Image: Aranda/Lasch, from Tooling].

(For more on Concrete Island, see BLDGBLOG’s own Concrete Island, in which those same quotations appear. Then, after you’ve express-ordered your own copy of Tooling – because any book with a chapter called “Computational Basketry” should be required reading – you can visit Benjamin Aranda’s and Chris Lasch’s work at the University of Pennsylvania’s Non-Linear Systems Organization, where they were recently research Fellows).