At one point in Owen Davies’s recent book Grimoires: A History of Magic Books, we read a short history of pirate treasure, lost gold, forgotten cities, and other “magical” artifacts of early colonial North America and the Caribbean, including what drove people to look for—and believe in—such things.

“America may not have been dotted with the ruined monasteries, castles, stone circles, dolmens, and hill forts that attracted treasure legends across Europe,” Davies writes, “but this did not prevent settlers from creating a new geography of treasure—one based on buried pirate booty supposedly secreted by the notorious William Kidd and Jean Lafitte, lost Spanish gold mines, and ancient Indian treasure.”

The West may have had its gold rush in the mid-nineteenth century but, long before, the countryside of the northeastern Atlantic seaboard was dotted with the exploration of those seeking hidden riches. In 1729 Benjamin Franklin co-wrote a newspaper essay highlighting the “problem,” bemoaning the great number of labouring people who were bringing their families to the brink of ruin in search of “imaginary treasure.” The physical signs of their activity were apparent around and about Philadelphia. “You can hardly walk half a mile out of Town on any side, without discovering several Pits dug with that Design,” Franklin moaned. He took a particular swipe at the role of astrologers, “with whom the Country swarms at this Time,” in promoting such fruitless endeavour.

This “popular preoccupation with treasure hunting,” as Davies describes it, created its own landscape, its “new geography of treasure”: a world of ceaseless, intuitive digging, tunneling downward with nothing at all like historical evidence but invigorated by the strong emotional conviction that something must be down there if only we can take it upon ourselves to look.

On the one hand, it’s fascinating to see that the orphan-like state of a newly liberated proto-United States would result in people so desperate for a sense of history that they might turn their own everyday world into a moonscape of excavations and craters—as if the “popular preoccupation with treasure hunting” was really the perverse acting-out of a society-wide mnemonic condition. History must still be around here somewhere, these excavations seem to say. And so new myths were created, swirling with “Indian treasure,” lost gold mines, secret cities in the mountain West, and stolen imperial fortunes locked away in pirate coves on the storm-sheltered sides of Caribbean islands.

[Image: From North By Northwest].

[Image: From North By Northwest].

I might even suggest that Alfred Hitchcock’s film North By Northwest (mentioned earlier) plays with some of these very themes, from its undisclosed imperial secrets hidden inside a Mesoamerican statue to the act of smuggling them through the Rocky Mountains by way of the massive tetrostatuary of Mt. Rushmore, stone totems of ancestral kings.

In any case, this urge for treasure—the need to dig—was not in any way limited to North America in its early Europeanization. During the so-called London treasure hunt riots, Londoners tore up properties all over the city “looking for one of 177 prize medallions which a Sunday newspaper called the Weekly Dispatch had planted around the UK.”

The paper used its first issue of the New Year to announce it had concealed a fortune in treasure medallions, the most valuable of which were worth £50 apiece. Each issue would carry a series of clues pointing to the prizes’ locations.

But these locations were incredibly vague, and, many readers thought, the only way to look was simply to start digging holes.

[Image: From Paul Slade, “London’s treasure hunt riots“].

[Image: From Paul Slade, “London’s treasure hunt riots“].

Quoting journalist Paul Slade at great length:

All over London, the story was the same. Crowds gathered outside Pentonville Prison and Islington’s Fever Hospital, blocking the roads and attacking any scrap of loose ground. Hundreds of treasure seekers converged on a Bethnal Green museum and began digging there. One Shooters Hill resident said his area was “infested with gangs of roughs.” Shepherd’s Bush, Clapton and Canning Town were besieged too.

By the time [a 19-year-old Battersea labourer called Frederick Nurse] had his day in court, Luton and Manchester had also been hit. Luton residents seeking the town’s single £10 medallion caused what councillors called “a gross disturbance” to the town in the early hours of Sunday, January 10. A week later, the Manchester Evening News found “some most extraordinary scenes” in its own city.

“From an early hour on Saturday night to late on Sunday night, various parts of the Manchester suburbs were the resort of men, women and children, people of all classes, drunk and sober, who had taken up what they thought to be the real clue to the spot where a medallion worth £25 lay hidden beneath the turf,” the [Manchester Evening News] reported. “They seized upon vacant pieces of land and stretches of roadway, digging and delving until not a foot of the ground lay smooth.” In Blackley, it added, three hunters had arrived simultaneously at the same spot and “settled the matter by a three-cornered fight.”

Indeed, Slade adds, “Wherever the Dispatch‘s promotion touched down, hysterical treasure hunters began tearing up the public highways with knives, shovels, sticks and any other implement that came to hand. If they took it into their head to dig up a private garden or vandalise the local park, they went right ahead and did so. Anyone who protested was bullied into submission… The promotion was less than three weeks old, and already causing chaos.”

This wasn’t even the only such “promotion”—other citywide treasure hunts, albeit resulting in less damage to personal property, were launched at the same time.

[Image: From Paul Slade, “London’s treasure hunt riots“].

[Image: From Paul Slade, “London’s treasure hunt riots“].

The cartoon from January 1904, included above, mocking the state of mind in which even a passing dream might really be an intuitive discovery of a buried treasure’s secret location, seems perfectly pitched here: convince people that there is something out there to be found—hidden gold or lost symbols—and a kind of neurosis for meaning breaks out. Everything is read and over-read, interpreted and over-interpreted. From the public craze for Dan Brown novels to Paul Slade’s “hysterical treasure hunters,” the urge to find something that you think has been hidden from you becomes all-consuming.

[Image: “Soldiers in the triumphal entry of Henri II into Rouen in 1550,” engraver unknown, from Mary Beard, The Roman Triumph].

[Image: “Soldiers in the triumphal entry of Henri II into Rouen in 1550,” engraver unknown, from Mary Beard, The Roman Triumph].

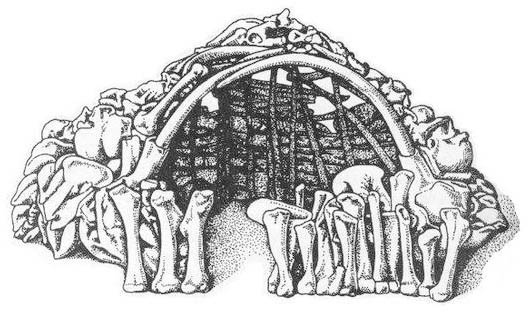

[Image: Mammoth bone hut; unknown illustrator].

[Image: Mammoth bone hut; unknown illustrator]. [Image: Alessandro Poli, Zeno-research of a self-sufficient culture (1979-80). ©Archivio Alessandro Poli. Photo: Antonio Quattrone. Courtesy of the

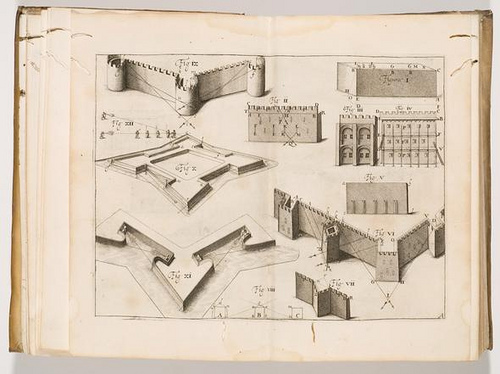

[Image: Alessandro Poli, Zeno-research of a self-sufficient culture (1979-80). ©Archivio Alessandro Poli. Photo: Antonio Quattrone. Courtesy of the  [Image: Unknown engraver, Series of views showing the development of the modern bastion system from its medieval origins, Matthias Dögen (1647), courtesy of the

[Image: Unknown engraver, Series of views showing the development of the modern bastion system from its medieval origins, Matthias Dögen (1647), courtesy of the

[Image:

[Image:  [Image:

[Image:

[Images:

[Images:

[Images:

[Images:

[Images:

[Images:

[Images:

[Images:

[Image: From

[Image: From  [Image: From Paul Slade, “

[Image: From Paul Slade, “ [Image: From Paul Slade, “

[Image: From Paul Slade, “

[Image: “

[Image: “

[Images: “

[Images: “

[Images: “

[Images: “

[Images: “

[Images: “

[Images: “

[Images: “

[Image: “

[Image: “ [Image: “

[Image: “ [Image: “

[Image: “ [Image: “Stonehenge at Night” (1944) by Harold Edgerton].

[Image: “Stonehenge at Night” (1944) by Harold Edgerton].

[Image: “A 1566 rendering of ‘terrible and curious’ quake damage” in Istanbul; courtesy of the

[Image: “A 1566 rendering of ‘terrible and curious’ quake damage” in Istanbul; courtesy of the

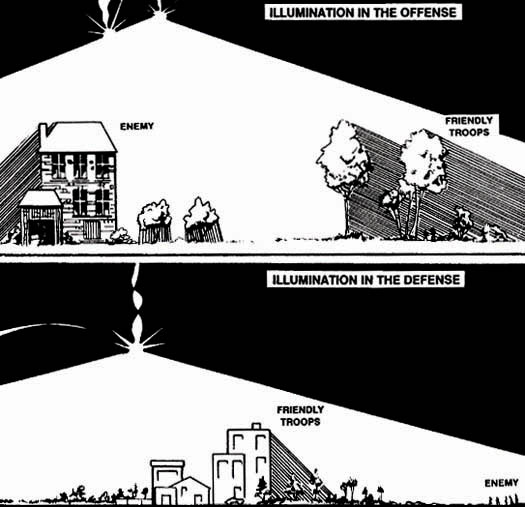

[Image: “Trip flares, flares, illumination from mortars and artillery, and spotlights (visible light or infrared) can be used to blind [the] enemy… or to artificially illuminate the battlefield,” from

[Image: “Trip flares, flares, illumination from mortars and artillery, and spotlights (visible light or infrared) can be used to blind [the] enemy… or to artificially illuminate the battlefield,” from  [Image: The Duplicative Forest—17,000 acres of identical trees—awaits; photo courtesy of

[Image: The Duplicative Forest—17,000 acres of identical trees—awaits; photo courtesy of  [Image: Archaeologists work at

[Image: Archaeologists work at