[Image: Disguised infrastructure; photo by BLDGBLOG].

[Image: Disguised infrastructure; photo by BLDGBLOG].

In the novel Foucault’s Pendulum, two characters discuss a house that is not what it appears to be. People “walk by” this house in Paris, we read, but “they don’t know the truth. That the house is a fake. It’s a facade, an enclosure with no room, no interior. It is really a chimney, a ventilation flue that serves to release the vapors of the regional Métro. And once you know this you feel you are standing at the mouth of the underworld…”

[Image: The door to the underworld; photo by BLDGBLOG].

[Image: The door to the underworld; photo by BLDGBLOG].

Two days ago, Nicola Twilley and I went on an early evening expedition over to visit the house at 58 Joralemon Street in Brooklyn, with its blacked out windows and its unresponsive front door.

This “house” is actually “the world’s only Greek Revival subway ventilator.” It is also a disguised emergency exit for the New York City subway.

[Image: Disguised infrastructure; photo by BLDGBLOG].

[Image: Disguised infrastructure; photo by BLDGBLOG].

According to a blog called the Willowtown Association, “the ventilator was a private brownstone dating from 1847. The substation was built in 1908 in conjunction with the start of subway service to Brooklyn. As reported in the BKLYN magazine article, the building’s ‘cavernous interior once housed a battery of electrical devices that converted alternating current to the 600-volt direct current needed to power the IRT.'”

[Image: A view through the front door of 58 Joralemon Street; photo by BLDGBLOG].

[Image: A view through the front door of 58 Joralemon Street; photo by BLDGBLOG].

It is New York’s more interesting version of 23/24 Leinster Gardens in London. As the Brooklyn Daily Eagle wrote last year, “the exit disguised as a brownstone leads to a grimy-lit set of metal stairs that ascend past utility boxes and ventilation shafts into a windowless room with a door. If you opened the door, you would find yourself on a stoop, which is just part of the façade.”

[Image: Photo by BLDGBLOG].

[Image: Photo by BLDGBLOG].

You’ll notice on Google Maps that the 4/5 subway line passes directly beneath the house, which brings to mind an old post here on BLDGBLOG in which we looked at the possibility that repurposed subway cars could be used someday as extra, rentable basement space—that is, “temporary basements in the form of repurposed subway cars,” with the effect that “each private residence thus becomes something like a subway station, with direct access, behind a locked door, to the subterranean infrastructure of the city far below.”

Then, for a substantial fee—as much as $15,000 a month—you can rent a radically redesigned subway car, complete with closets, shelves, and in-floor storage cubes. The whole thing is parked beneath your house and braked in place; it has electricity and climate control, perhaps even WiFi. You can store summer clothes, golf equipment, tool boxes, children’s toys, and winter ski gear.

When you no longer need it, or can’t pay your bills, you simply take everything out of it and the subway car is returned to the local depot.

A veritable labyrinth of moving rooms soon takes shape beneath the city.

Perhaps Joralemon Street is where this unlikely business model could be first tried out…

In any case, Nicola and I walked over to see the house for a variety of reasons, including the fact that the disguised-entrance-to-the-underworld is undoubtedly one of the coolest building programs imaginable, and would make an amazing premise for an intensive design studio; but also because the surface vent structures through which underground currents of air are controlled have always fascinated me.

These vents appear throughout New York City, as it happens—although Joralemon, I believe, is the only fake house—serving as surface articulations of the larger buried networks to which they are connected.

[Image: Two views of the tunnel vent on Governors Island; photos by BLDGBLOG].

[Image: Two views of the tunnel vent on Governors Island; photos by BLDGBLOG].

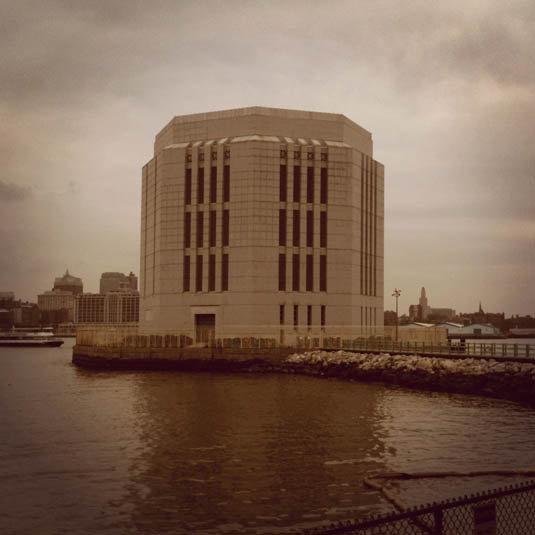

The Battery Tunnel has a particularly noticeable vent, pictured above, and the Holland Tunnel also vents out near my place of work.

[Image: Holland Tunnel exhaust tower; photo via SkyscraperPage.com].

[Image: Holland Tunnel exhaust tower; photo via SkyscraperPage.com].

As historian David Gissen writes in his excellent book Subnature: Architecture’s Other Environments, New York’s ventilation control structures are “strange buildings” that have “collapsed” the difference between architecture and civil engineering:

The Holland Tunnel spanned an enormous 8,500 feet. At each end, engineers designed ten-story ventilation towers that would push air through tunnels above the cars, drawing the vehicle exhaust upward, where it would be blown back through the tops of the towers and over industrial areas of the city. The exhaust towers provided a strange new building type in the city—a looming blank tower that oscillated between a work of engineering and architecture.

As further described in this PDF, for instance, Holland Tunnel has a total of four ventilation structures: “The four ventilation buildings (two in New Jersey and two in New York) house a total of 84 fans, of which 42 are blower units, and 42 are exhaust units. They are capable, at full speed, of completely changing the tunnel air every 90 seconds.”

[Image: The Holland Tunnel Land Ventilation Building, courtesy of Wikipedia].

[Image: The Holland Tunnel Land Ventilation Building, courtesy of Wikipedia].

Several years ago a friend of ours remarked that she didn’t like staying in hotels near Columbus Circle here in New York because that’s the neighborhood, she said, where all the subways vent to—a statement that appears to be nothing more than an urban legend, but that nonetheless sparked off a long-term interest for me in finding where the underground weather systems of New York City are vented to the outside. Imagine an entire city district dedicated to nothing but ventilating the underworld!

[Image: The house on Joralemon Street; photo by BLDGBLOG].

[Image: The house on Joralemon Street; photo by BLDGBLOG].

This is a topic I will no doubt return to at some point soon—but, for now, if you want to see a disguised entrance to the 4/5 line, walk down Joralemon Street toward the river and keep your eyes peeled soon after the street turns to cobblestones.

(The house on Joralemon Street first discovered via Curbed).

[Image: An otherwise unrelated image of the unmanned

[Image: An otherwise unrelated image of the unmanned

[Images: Might semi-autonomous systems such as this someday track residential property lines? Images courtesy of

[Images: Might semi-autonomous systems such as this someday track residential property lines? Images courtesy of

[Image: Assembling the 7-mile rainbow one ring at a time, by Ben Masterton-Smith].

[Image: Assembling the 7-mile rainbow one ring at a time, by Ben Masterton-Smith].

[Image: Assembling the rainbow; images by Ben Masterton-Smith].

[Image: Assembling the rainbow; images by Ben Masterton-Smith]. [Image: The glorious 7-mile rainbow takes form].

[Image: The glorious 7-mile rainbow takes form].

[Images: Rainbow diagrams by Ben Masterton-Smith].

[Images: Rainbow diagrams by Ben Masterton-Smith]. [Image: The rainbow under construction; image by Ben Masterton-Smith].

[Image: The rainbow under construction; image by Ben Masterton-Smith].

[Image: From the

[Image: From the

[Images: From the

[Images: From the

[Image: The erstwhile basement hibernator, photographed by Brendan Kuty/Patch.com, via

[Image: The erstwhile basement hibernator, photographed by Brendan Kuty/Patch.com, via

[Image: The

[Image: The  [Images: Photos of Picher’s artificial landforms, courtesy of the

[Images: Photos of Picher’s artificial landforms, courtesy of the

[Images: A

[Images: A

[Images: Sections through the

[Images: Sections through the  [Image: Inside the “

[Image: Inside the “

[Image: Untitled, Diana Balmori (2010), via

[Image: Untitled, Diana Balmori (2010), via

[Image: “Sunset Bulbs” by

[Image: “Sunset Bulbs” by

[Images: (top) “Convergence” and (bottom) “Christmas” by

[Images: (top) “Convergence” and (bottom) “Christmas” by

[Images: (top) “White Street,” (second from top) “Ocean Circle”, (second from bottom) “Jean Street,” and (bottom) “Caraway Street,” all by

[Images: (top) “White Street,” (second from top) “Ocean Circle”, (second from bottom) “Jean Street,” and (bottom) “Caraway Street,” all by

[Images: (top) “Bushes” and (bottom) “Pebble Street” by

[Images: (top) “Bushes” and (bottom) “Pebble Street” by  [Image: “The Dragon” by

[Image: “The Dragon” by

[Images: (top) “Ocean Place” and (bottom) “Ocean Street” by

[Images: (top) “Ocean Place” and (bottom) “Ocean Street” by

[Image: A nearly empty banana truck; photo by the author].

[Image: A nearly empty banana truck; photo by the author]. [Image: The Lovecraftian doors of the banana crypt; photo by the author].

[Image: The Lovecraftian doors of the banana crypt; photo by the author].

[Image: The defused Koblenz bomb is lifted to safety].

[Image: The defused Koblenz bomb is lifted to safety]. [Image: Part of the Space Shuttle Columbia; photo courtesy of the

[Image: Part of the Space Shuttle Columbia; photo courtesy of the

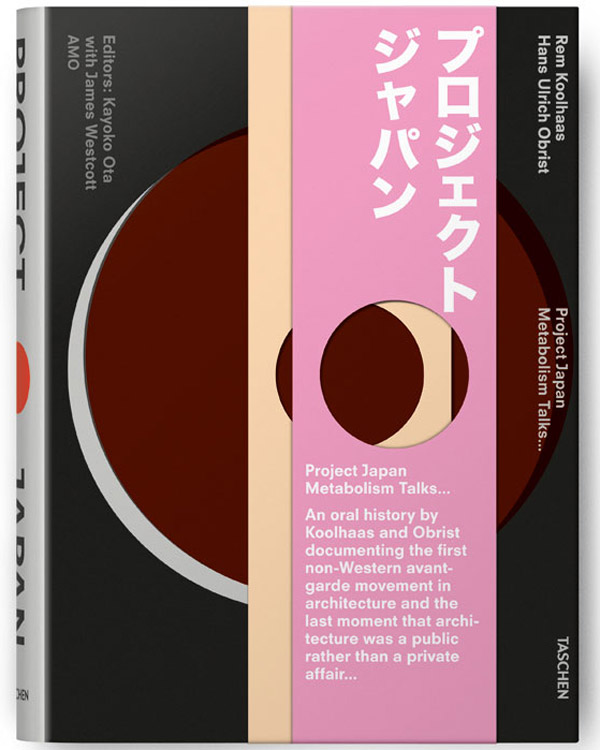

[Images: Spreads from Project Japan, courtesy of

[Images: Spreads from Project Japan, courtesy of

[Images: Photos by Soe Than Win/AFP/Getty Images, courtesy of

[Images: Photos by Soe Than Win/AFP/Getty Images, courtesy of  [Image: An “insect cyborg” via

[Image: An “insect cyborg” via  [Image: Photo by

[Image: Photo by

[Image: Window by

[Image: Window by