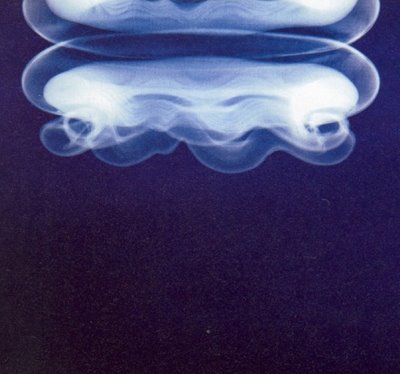

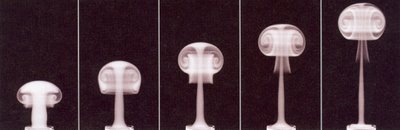

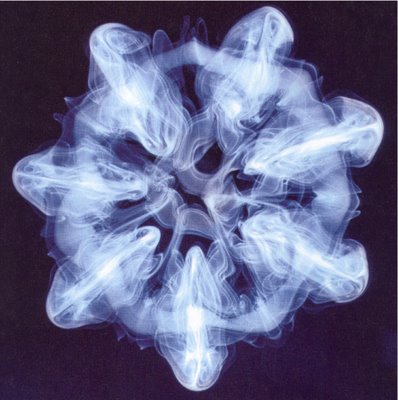

[Images: The structural science of vortex rings. “A vortex ring forms when a very quick burst of fluid shoots out of an opening,” Freud writes – er, this article tells us. “As the fluid moves forwards, it spreads out and its front edges curl back. If the speed of the burst is fast enough, the curling fluid eventually curls all the way round, until it is travelling forwards again in the direction of the original burst.” Etc. So could such vortices be used as a new form of undersea propulsion – or perhaps an underwater art show, perfect vortices spiraling off through colored water, liquid crystals, magma? If you’re still curious, this PDF version of the New Scientist article mentioned above will tell you all about the fluid-mechanical work of Kamran Mohseni and Mory Gharib, including a brief aside on “superfluid gyros” and “vortex-formation velocity.”]

Author: Geoff Manaugh

Paper topographies: 1

Though I may be late to the game here, I’ve recently discovered the origami of Eric Gjerde. These are all examples of his work, taken from Eric’s various flickr sets: surface become structure; paper, terrain; folds made into space and topography.

Methods, tips, techniques, etc., can all be found on his website.

(Somewhat related: the paper sculptures of Richard Sweeney).

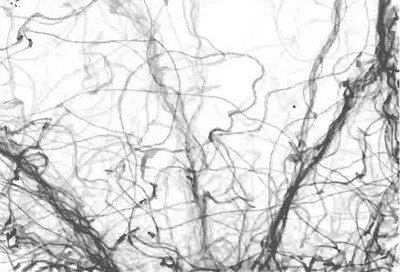

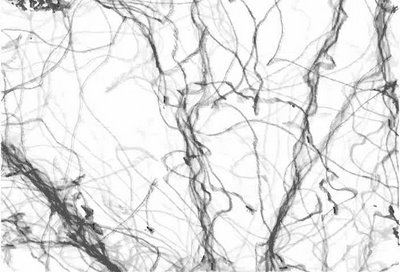

Tracking Ants

Continuing our recent, if somewhat unexpected, ant theme, here is a project that maps the paths of walking ants.

The project, by Sean Dockray, consists of a short video loop that “documents a pheromonal portrait made by Argentine ants. While the ants in the video are real (they were shot in a single 45 minute long take) the trails are created in a piece of custom software, which tracks each ant frame-by-frame.”

“The more that ants walk on a particular path, the darker that paths gets. Over time, the paths either disappear or are reinforced by more walking. In this way, the video is a kind of mutable, spatialized collective memory.”

(See also Wormholes in Wood, and the almost unbelievable images of subterranean ant architecture at Nest-casting; and thanks to Sean Dockray for supplying the filmstills!).

Absolute Superlinearity

The Gear Tek Corporation takes us on a brief visit to “the longest building I have ever seen,” located somewhere in the “physically oppressive and hallucinatory” flatlands of Illinois.

“This is the longest building I have ever seen,” GTC writes. “It is totally windowless and stretches for at least a mile, although it seems to defy laws of space-time so it may be longer or shorter than that.”

The building’s absolute superlinearity appears to be a “spatial illusion” that is only amplified by the “simple gray rectangles which glide along the blank facade like dotted lines on an overlay. It looks like an Ellsworth Kelly interpretation of Superman chasing a train.”

(Links to the original Gear Tek Corporation post have been removed because the URL now resolves to a porn site. Thanks to Tim Drage for the tip!)

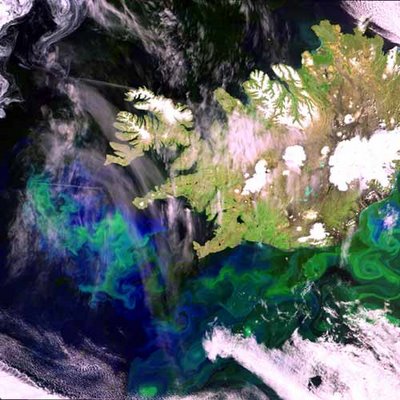

Glowing oceans

[Image: Here we see phytoplankton illuminating the Denmark Strait, forming solar-mineral arabesques, glowing traces. “While phytoplankton are tiny taken by themselves, together they can cause color shifts in ocean water, which in turn is detected by orbiting spacecraft.” Next, you build triangular frames, squares and circles afloat on the ocean – then fill them all in with phytoplankton: a sea of shining geometry. Cubes of light cast adrift across the North Sea, photographed from below by divers. Courtesy European Space Agency].

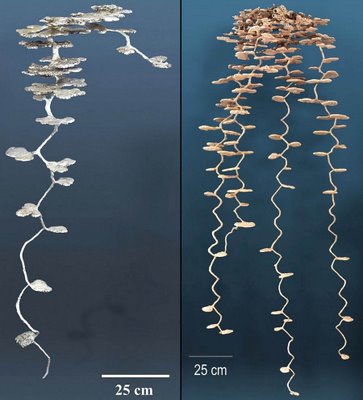

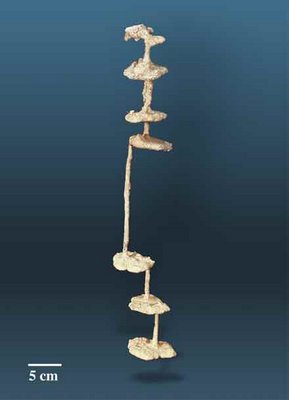

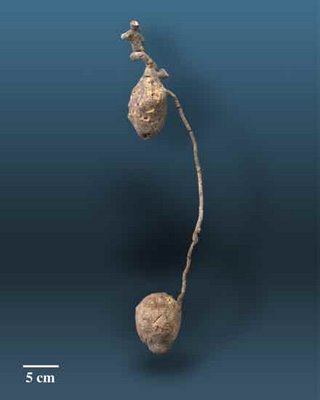

Nest-casting

In the Fall of 2001, Cabinet Magazine introduced us to Walter Tschinkel, a professor of entomology at Florida State University. Tschinkel “has been making plaster casts of ant nests since 1982, when he first heard of the strength of orthodontic plaster. The painstaking process involves pouring the plaster down the opening as quickly as it will go in. After the plaster hardens, the excavation begins, but the nest must be taken out piece by piece. (One harvester ant nest, for example, took some five gallons of plaster and came out in 180 pieces.)”

“Sometimes more than ten feet tall, the nests are as beautiful in structure as they are complex.”

In a fascinating research paper (available through Florida State University as a PDF), Tschinkel describes subterranean ants’ nests as “shaped voids in a soil matrix.” These casts, Tschinkel tells us, offer “an invaluable way to visualize ant colonies as they are, that is as a three-dimensional network of tunnels and chambers.”

In an even more interesting – not to mention better illustrated – paper (also available as a PDF) Tschinkel takes us on a verbal tour of this buried architecture: “In contrast to shafts,” he writes, the chambers all “had more or less horizontal floors and a horizontal outline ranging from near circular when small, to multi-lobed when large. In vertical cross-section, they were flattened or slightly domed, with the horizontal dimension much greater than the vertical. All chambers were about 1 cm high, floor to ceiling, no matter what the floor area. Shafts usually intersected chambers at an edge, and connected sequential chambers. Below about 15 to 20 cm, chambers always began as lateral, horizontal-floored extensions from the outside of a spirally-descending shaft that therefore intersected the inner edge of the chamber at an angle ranging from 25º to about 70º.”

The social behavior of the ants is, in many ways, what produces the structures. Tschinkel refers to “movement zones,” in which “partially overlapping sequences from the center of the nest to the periphery” are traced and retraced by individual ants. These movements gradually erode at the walls, expanding surfaces into actual rooms. These “spaces,” then, are really the physical results of social activity, in which a surface becomes a route becomes a chamber – and further branchings spread outward (or downward) from there. (Substantially more information on this – including the influential role of carbon dioxide – can be found in this PDF).

“Chamber morphology,” meanwhile, “was rarely elongated and shaft-like.” Rather, each chamber “began as a niche in the outer wall of a shaft.” Etc. etc.

The process of making these casts almost always kills the ants in the nests, however; but that is “not something I like doing,” Tschinkel says.

Of course, the urge toward revealing invisible architecture can overwhelm even the best…

(Thanks to jpb for the link! And this post is directly related to an earlier post, Wormholes in Wood, which discusses the more conceptual aspects of such a project).

Air Wonder Stories

This 1929 cover from an American speculative fiction magazine inspired Janey Cook to rebuild that fantastic sky city using Lego.

[Images: New air city by Janey Cook; photographs by Calum Tsang and Allan Bedford. Air Wonder Stories cover from Frank R. Paul’s online gallery of sci-fi cover art. More covers coming up soon, in fact, because most of them are completely ridiculous – though architectural. Meanwhile, see the Lego Escher at gravestmor and, of course, The Brick Testament].

(Thanks to Peter Hoh for the link!)

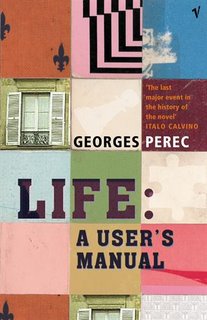

Wormholes in Wood

Emilio Grifalconi, a character in Georges Perec’s 1978 novel Life: A User’s Manual, at one point discovers “the remains of a table. Its oval top, wonderfully inlaid with mother-of-pearl, was exceptionally well preserved; but its base, a massive, spindle-shaped column of grained wood, turned out to be completely worm-eaten. The worms had done their work in covert, subterranean fashion, creating innumerable ducts and microscopic channels now filled with pulverized wood. No sign of this insidious labor showed on the surface.”

Grifalconi soon realizes that “the only way of preserving the original base – hollowed out as it was, it could no longer suport the weight of the top – was to reinforce it from within; so once he had completely emptied the canals of the their wood dust by suction, he set about injecting them with an almost liquid mixture of lead, alum and asbestos fiber. The operation was successful; but it quickly became apparent that, even thus strengthened, the base was too weak” – and the table would have to be discarded.

In preparing to get rid of the table, however, Grifalconi stumbles upon the idea of “dissolving what was left of the original wood” that still formed the table’s base. This would “disclose the fabulous arborescence within, this exact record of the worms’ life inside the wooden mass: a static, mineral accumulation of all the movements that had constituted their blind existence, their undeviating single-mindedness, their obstinate itineraries; the faithful materialization of all they had eaten and digested as they forced from their dense surroundings the invisible elements needed for their survival, the explicit, visible, immeasurably disturbing image of the endless progressions that had reduced the hardest of woods to an impalpable network of crumbling galleries.”

And if we could sculpt and harden our own paths through cities – across continents – what wormholes of structure and space might we find?

(Earlier on BLDGBLOG: Wormholes).

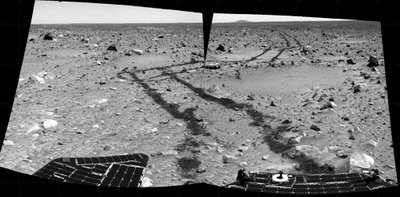

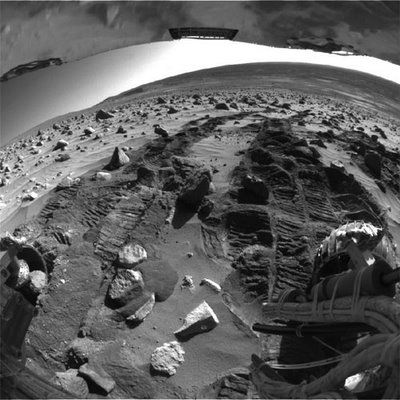

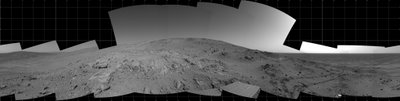

A Mars Supreme

[Images: As if Kazimir Malevich had been reincarnated on Mars to take panoramic geological photography – a new Suprematism of alien terrain – these images are all strangely framed black and white shots like filmstills, taken by NASA’s Spirit rover; courtesy of NASA/JPL-Caltech].

(Earlier: Mars Rover: A New Film by BLDGBLOG).

The total horizon

These are all photographs of Tokyo taken by Shintaro Sato (©) – click on images for original, and much bigger, versions. This one is particularly great.

(Via the graphic wizards at Coudal Partners).

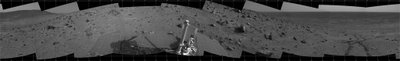

Autistic Canyons, Icebergs of War, and Architecture Made From Light

Much has been made over the past ten days of Stephen Wiltshire, an autistic artist based in London. Given an aerial tour of Rome, for instance, Wiltshire soon reproduced the whole city, in astonishing detail, down to the correct number of arches on the Coloseum – drawing the sketch from memory.

Extraordinary though his sketches may be – I like London’s Albert Hall, personally, though Wiltshire’s oil painting of Los Angeles traffic is also pretty cool – what really got me thinking were the implications this might have for other art forms.

Construction, for instance.

What would happen if you flew a group of autistic miners and bulldozer drivers over the Grand Canyon for several hours? Maybe you even go back the next day, fly circles over certain formations, bank the wings. Memorize fault geometry, strike and dip, the Vishnu schist. Your passengers stare out the window and think. They don’t touch their peanuts. They wear seatbelts.

The whole Grand Canyon, up every tributary and side-fractal’d edge, eroded half-canyons of loose pebbles tumbling under footsteps; fissures, gaps.

You then unleash everyone on the plains of central Asia with a fleet of picks and bulldozers: could they exactly reproduce the Grand Canyon? I think they could. I think Stephen Wiltshire could. Give him a jackhammer and come back in two years.

Such questions have been posed on BLDGBLOG before, of course, but couldn’t that negative earthwork, that unzipped void, be copied exactly to scale? How long would it take? How precise would it be?

Milling new autistic canyons into the surface of the planet.

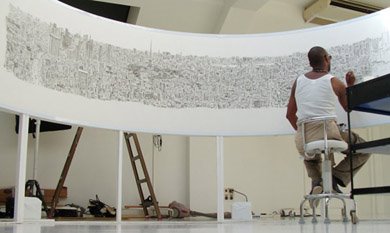

Meanwhile, the Kircher Society, who introduced us to Stephen Wiltshire, also informed us this week that a “massive floating island 2,000 feet long, 300 feet wide, and 40 feet thick” was almost built by the British military during WWII. Called Pykrete, the material it would have been made from was an “almost indestructible mixture of ice and wood pulp” – though it’s elsewhere been described as “a compound [made] out of paper pulp and sea water which was almost as strong as concrete” (not quite indestructible, then).

Either way, Pykcrete (also spelled “Pykecrete”) would have been used in all manner of ocean-borne construction projects, including a ship that “would serve as a sort of glacial aircraft carrier” in times of war.

Pykcrete structures could not only float, they could repel bullets – an accurate description, on both counts, of my uncle…

Finally, New Scientist gives us the low-down on structures made from light.

Resembling some kind of Renaissance magic trick, a metal work surface “covered with lenses, prisms and mirrors” can now be used to create solid structures out of light – but only if you’ve got “polystyrene beads a few hundred nanometres across.”

“With a flick of a switch,” New Scientist explains, a laser “bathes the beads in an invisible web of infrared light and immediately the beads start collecting… First one or two, then perhaps a dozen fall into line. The beads are still jostling, but something much stronger is holding them in place. Other beads cluster around, seemingly reluctant to join the group. But one by one, they take the plunge, somehow forced into the growing array. Eventually the beads form a chessboard array bound together like a crystal.”

This experiment was conducted by Colin Bain, a chemist at England’s Durham University. He has made what’s called “optical matter” – even “optical cement.”

Of course, architectural metaphors are never far off: “In this microscopic construction site,” we read, “light acts as architect, bricklayer and construction worker, turning building blocks, into temples.”

Bain can change the structures he builds simply by changing the polarization of the light; thus, “suddenly the hexagonal array flips into a square one.” Wavelength, frequency, structure.

Meanwhile, optical researchers Jean-Marc Fournier and Tomasz Grzegorczyk “have big ambitions for optical matter. They are investigating ways to build a giant mirror made from particles bound together entirely by laser light. Such a mirror could be a boon for future space telescopes.” Specifically, they’d use a laser to “trap” particles, which would then “self-organise into a thin reflecting film that takes the shape of a focusing mirror.”

This mirror would apparently be “self-healing.”

Next up: skyscrapers, emergency tents, hydroelectric dams, whole suburbs – created with a single beam of light…

Several months ago, NPR’s Science Friday aired a show called “Stopping Light” – in which the host, Ira Flatow, interviews an Australian physicist. At one point, as if he hasn’t been paying attention, Flatow mutters the strangely uncomfortable, Muppet-like phrase: “Mmm… An archive.”

Download the MP3 right here.

(Earlier on BLDGBLOG: A cubic meter of fogged space, and – a personal favorite of mine – A Natural History of Mirrors. And thanks, Leah B., for the tip on Pykrete!)