[Image: National Geographic: “A spelunker in a glacier cave in Greenland gazes upon colors and shapes that look more like a swirling galaxy than a cave formation.” Photo by Carsten Peter].

[Image: National Geographic: “A spelunker in a glacier cave in Greenland gazes upon colors and shapes that look more like a swirling galaxy than a cave formation.” Photo by Carsten Peter].

Having now spent every available moment of every day for more than a week stuck inside Storefront for Art and Architecture, painting the floors and walls, installing vinyl, coordinating deliveries, sweeping up loose tape and sawdust, and more, I’ve decided to upload a slightly longer than normal cache of links. It might be a few more days before I can post again.

I hope to see some of you at the exhibition opening, though, which takes place Tuesday, March 9, at 7pm: Landscapes of Quarantine.

[Image: The future is not what it used to be: MIT’s thresholds seeks essays on critical futurism].

[Image: The future is not what it used to be: MIT’s thresholds seeks essays on critical futurism].

thresholds 38 | Futures: Call for Submissions: “Whether it is a revolt against the futures of the past or a curiosity towards the unknown, thresholds 38 invites methods, projects, practices and alternative kinds of critique that imagine unorthodox futures that can emerge from within this institution.” Submissions due March 12.

Synthetic Aesthetics | Call for Participants: “We seek participants for a project on synthetic biology, design, and aesthetics. The project will provide funding to bring together scientists and engineers working in synthetic biology with artists, designers, and other creative practitioners.”

Synthetic biology is broadly defined as the design and construction of new biological parts, devices, and systems, and the re-design of existing biological systems for useful purposes. Design is central to synthetic biology, as the living world becomes a product of design and manufacturing choices, rather than evolutionary pressures alone. Thus, it becomes important to ask what role design–and the related concept of aesthetics–play in this burgeoning field. Other forms of engineering and manufacturing work in close conjunction with creative practitioners: structural engineers work with architects; mechanical engineers with product designers. Can synthetic biology benefit similarly from such collaborations?

Applications due March 31.

Open Agenda | Call for Submissions: “Open Agenda is a new annual competition aimed at supporting a new generation of experimental Australian architecture. Open to recent architecture graduates, Open Agenda is focused on developing the possibilities of design research in architecture and the built environment… Open Agenda will award seed funding to three exceptional design research proposals that explore new positions in architecture for critical consideration.” Register by May 1.

[Image: The Niagara Falls without their water, photographed by Flickr user rbglasson, via mammoth].

[Image: The Niagara Falls without their water, photographed by Flickr user rbglasson, via mammoth].

mammoth | Absent Rivers, Ephemeral Parks: “For six months in the winter and fall of 1969, Niagara’s American Falls were ‘de-watered’ as the Army Corps of Engineers conducted a geological survey of the falls’ rock face, concerned that it was becoming destabilized by erosion. During the interim study period, the dried riverbed and shale was drip-irrigated, like some mineral garden in a tender establishment period, by long pipes stretched across the gap, to maintain a sufficient and stabilizing level of moisture. For a portion of that period, while workers cleaned the former river-bottom of unwanted mosses and drilled test-cores in search of instabilities, a temporary walkway was installed a mere twenty feet from the edge of the dry falls, and tourists were able to explore this otherwise inaccessible and hostile landscape.”

BBC | North Tyneside high street “revived” by fake shop front: “Fake businesses are to be used to lessen the impact of the recession on high streets in North Tyneside… The government-funded project involves colourful graphic designs featuring a range of different shop types, which are either taped inside the windows or screwed to the fascia so they can be removed and reused as required.”

InfraNet Lab | Terrestrial Discontinuities: “…these [energy corridors in the western United States] range from 3,500-feet wide to upwards of 5 miles wide. With these widths, we could almost begin to see these corridors as an ecology in and of themselves—rather than an ecology competing with National Parks, they could become the New National Parks, infrastructural vectors, protected as natural reserves by virtue of their very danger to us.”

Guardian | Greece should sell islands to keep bankruptcy at bay: “Greece must consider a fire sale of land, historic buildings and art works to cut its debts, two rightwing German politicians said today in a newspaper interview that is bound to exacerbate tensions between Athens and Berlin. Alongside austerity measures such as cuts to public sector pay and a freeze on state pensions, why not sell a few uninhabited islands…” It might be ethically wrong, as well as politically dubious, and I have no money, but BLDGBLOG would certainly buy one. The Sovereign Neo-Cyclades.

[Image: Tactical drone seed-bombing, courtesy of Design Under Sky].

[Image: Tactical drone seed-bombing, courtesy of Design Under Sky].

Design Under Sky | Ludic Guerrilla Gardening Drone Warfare: “…with recent advancements in augmented reality and virtual gaming, I can’t help but imagine that a new style of drone-based urban landscape replenishment isn’t a far off possibility.”

Post-Traumatic Urbanism | Mediterranean Union: “A [high-speed rail] line running along the Mediterranean littoral is a seemingly impossible idea based in visionary assumptions. After all, it would need to pass through a region mired by instability and fractured by impenetrable borders. Functioning like a conveyor at the scale of continents, it would redistribute flows of people, warping the space-time fabric of an entire region—linking long disputed territories and as yet unformed nations. It would string together a seemingly impossible series of names: Gaza, Barcelona, Beirut, Haifa, Tel Aviv, Cairo. In doing so it would open a conduit between the differential pressures of North Africa and Europe—all this in the context of EU policy that increasingly conceives of Southern Europe as a bulwark against refugees. The political question we asked ourselves is the following one: what are the emancipatory potentials of infrastructure?”

City of Sound | Notes on New Songdo City (Part 1): “…it occurs to me that the logical thing to do would be the greatest engineering project of the next centuries; quite possibly the greatest diplomatic and economic project of the next centuries too, linking Japan with China via Korea via a high-speed rail link across gigantic bridges.”

Spaceinvading | Sandwiched by INABA: “As part of the 2010 Whitney Biennial, Jeffrey Inaba’s firm INABA was commissioned to design a pop‐up café located in the museum’s interior courtyard. The project consists of three large‐scale lanterns that occupy the courtyard’s double‐height space; a 24‐foot long service counter; communal tables; high‐top counters; and ‘droopy’ seat cushions.”

[Image:

[Image: Project by CJ Lim Image by Squint/Opera for Grant Associates].

SCI-Arc | London Eight Exhibition: “SCI-Arc presents London Eight, curated by renowned English architect Sir Peter Cook. A founding member of the 1960s futurist group Archigram and a visiting faculty member at SCI-Arc, Cook invited five architects who currently teach at the Bartlett School of Architecture, University College London, where Cook was professor from 1990 to 2005, to participate in an exhibition at the SCI-Arc Library Gallery. These architects were then asked to select a ‘protege’ whom they had mentored through their studies at the Bartlett to exhibit alongside their own work in the gallery.” Includes work by Smout Allen, Johan Hybschmann, Marjan Colletti & Marcos Cruz, Yousef Al-Mehdari, CJ Lim, and Pascal Bronner.

Hudson Valley Seed Library | “The Hudson Valley Seed Library strives to do two things: to create an accessible and affordable source of regionally-adapted seeds that is maintained by a community of caring gardeners; and, to create gift-quality seed packs featuring works designed by New York artists in order to celebrate the beauty of heirloom gardening.”

Urban Forest Map | “The Urban Forest Map is a collaborative project among city agencies, tree advocacy groups, and citizen foresters like you to map every tree in San Francisco, which will help protect and expand our urban forests.”

GOOD | Fallen Fruit’s Tree-planting Dreams Are Uprooted In Madrid: “For the last 10 days Fallen Fruit had been scouring the area [around Madrid], leading urban foraging trips to find what other fruit-bearing trees existed in the neighborhood around the city-funded Matadero art space, plotting the best locations for future apples, peaches, plums, pears, and apricots… The plan was to have the trees planted before their final presentation that night, giving the people of Madrid a map to all the public fruit they could eventually eat.”

Cleveland Plain Dealer | Galleria mall is giant greenhouse, raising organic crops in Cleveland: “…by late spring or early summer, there will be fresh tomatoes for sale among the shops and galleries at the downtown Cleveland mall. Very fresh—as in vine-grown in bags and troughs hanging from steel stair banisters and ceiling beams in the shopping center that stretches between East Ninth and East 12th streets.”

[Image: King’s Vineyard, London by Soonil Kim, via Pruned].

[Image: King’s Vineyard, London by Soonil Kim, via Pruned].

Pruned | King’s Vineyard, London: “One can certainly imagine such a network [of aerial vineyards and urban viticultural installations] built to grow others things, such as vegetables, herbs, fruits, cash crops, commercial flowers and plants, with the winery turned into a farmer’s market.”

Independent | Syria’s Stonehenge: Neolithic stone circles, alignments and possible tombs discovered: “Dr. Mason explains that he ‘went for a walk’ into the eastern perimeter of the site—an area that hasn’t been explored by archaeologists. What he discovered is an ancient landscape of stone circles, stone alignments and what appear to be corbelled roof tombs. From stone tools found at the site, it’s likely that the features date to some point in the Middle East’s Neolithic Period—a broad stretch of time between roughly 8500 BC – 4300 BC. It is thought that in Western Europe megalithic construction involving the use of stone only dates back as far as ca. 4500 BC. This means that the Syrian site could well be older than anything seen in Europe.”

New York Times | A Jewish Ritual Collides With Mother Nature: “From Washington to New York State, a series of ‘snowmageddons’ have wreaked a particular form of havoc for Orthodox Jews. The storms have knocked down portions of the ritual boundary known as an eruv in Jewish communities… Almost literally invisible even to observant Jews, the wire or string of an eruv, connected from pole to pole, allows the outdoors to be considered an extension of the home. Which means, under Judaic law, that one can carry things on the Sabbath, an act that is otherwise forbidden outside the house. Prayer shawls, prayer books, bottles of wine, platters of food and, perhaps most important, strollers with children in them—Orthodox Jews can haul or tote such items within the eruv. When a section of an eruv is knocked down by, let’s say, a big snowstorm, then the alerts go out by Internet and robocall, and human behavior changes dramatically.”

Spillway | Why Ambassador, With This Perimeter You Are Really Spoiling Us: “One progresses from queue to queue before entering the building, progressing to slightly higher echelons of security clearance each time depending on the paperwork one has brought with one. Unsmiling police officers with automatic weapons stare at you, and you realize that if you made a dash towards the building itself, you would have to enter an area of open space that designed as a killzone, surrounded by armed representatives of the Metropolitan constabulary. Behind crossfire plaza is the building itself, its generous Scandinavian spaces seemingly as distant as the country you are trying to visit. The contradictions of that space are horribly unsettling, with a strongly dystopian odour: we can see the structures of a democracy retrofitted with the apparatus of authoritarianism. It gives a sense of how far we’ve fallen in 10 years.”

[Image: The “High Houses” of Lebbeus Woods].

[Image: The “High Houses” of Lebbeus Woods].

Lebbeus Woods | High Houses: “The High Houses are proposed as part of the reconstruction of Sarajevo after the siege of the city that lasted from 1992 though late 1995. Their site is the badly damaged ‘old tobacco factory’ in the Marijn dvor section near the city center.”

Serial Consign | Toronto Sound Ecology: “Toronto Sound Ecology is a web mapping project dedicated to archiving field recordings collected in and around Toronto.”

Some landscapes | Alpine Symphony: “Birdsong, thunderstorms and flowing water are pretty standard, but… would it be possible to move away from the sublime and the picturesque, to convey more unusual settings or simply nondescript landscapes through purely orchestral sound?”

Google Earth Blog | Solving a Murder With Google Earth: “On January 24, 2006, Jennifer Kesse vanished. The police quickly determined that she was abducted, but nothing solid has turned up in the past four years… During this time, users on her site discussed the new events and came to a stunning revelation: using Google Earth’s historical imagery, they found an image from approximately one month after she disappeared. The image seems to show some promising information.”

Related from last summer: Sydney Morning Herald | Mugging suspects snapped by Google Street View: “Dutch police have arrested twin brothers on suspicion of robbery after their alleged victim spotted a picture of them following him on Google Map’s Street View feature.”

National Geographic | Quintana Roo Underwater Cave Project: “Beneath the jungles of the Yucatan peninsula, [Sam] Meacham and his team are exploring and mapping the longest underwater cave system in the world.” See also: Blue Holes Project: “Blue holes can run extremely deep underground, with one Bahamian blue hole exceeding 600 feet (180 meters) below sea level, and contain a series of mazelike passageways going miles in many directions. These cave systems can transition from giant rooms to tiny holes that divers must remove all of their gear in order to squeeze through. To add to the challenge, currents reverse in the ocean caves, making timing of dives critical.”

[Image: Architizer comes to Los Angeles].

[Image: Architizer comes to Los Angeles].

Architizer | Los Angeles Launch Announcement: “We are happy to announce that on March 18th, we will be hosting a party in Los Angeles at the new A+D Museum space [at 6032 Wilshire Boulevard]. In partnership with Haworth, Dwell Magazine, LA Forum, SCI-Arc, and BLDGBLOG, the event will be an evening to meet fellow Los Angeleno architects as well as a celebration of Los Angeles architecture culture.” Here is a map. If you’re in LA, stop by and say hello!

[Image: Rendering of the new A+D Museum].

[Image: Rendering of the new A+D Museum].

(Some links via @doingitwrong, @javierest, @geoparadigm, @stevesilberman, and possibly elsewhere. Don’t miss Quick Links 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 and 7).

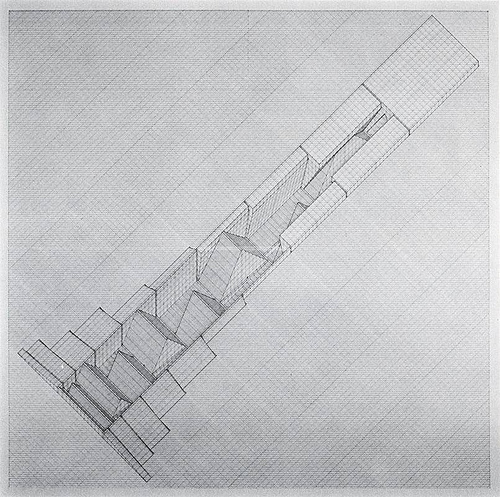

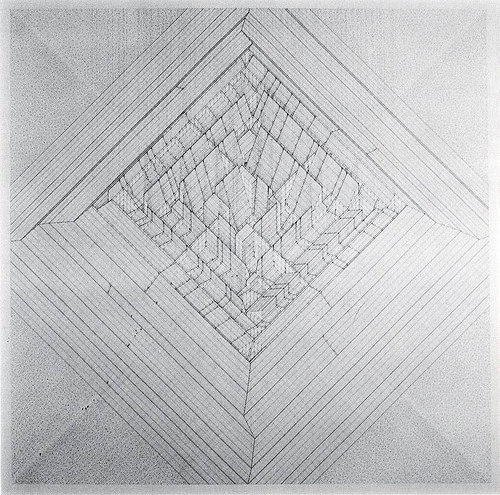

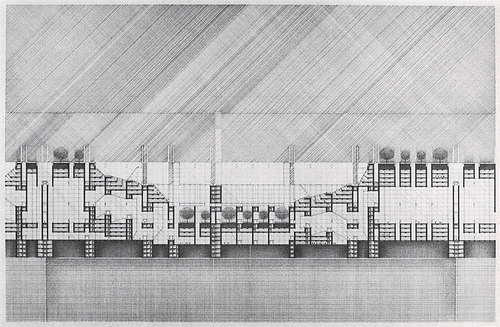

[Image: ONECITY by Will Insley; image via The Nonist].

[Image: ONECITY by Will Insley; image via The Nonist].

[Images: ONECITY by Will Insley, via The Nonist].

[Images: ONECITY by Will Insley, via The Nonist].

[Images: ONECITY by Will Insley].

[Images: ONECITY by Will Insley]. [Images: ONECITY by Will Insley].

[Images: ONECITY by Will Insley].

[Images: From Vider Paris (1998-2001) by Nicolas Moulin, courtesy of

[Images: From Vider Paris (1998-2001) by Nicolas Moulin, courtesy of  [Images: From Vider Paris (1998-2001) by Nicolas Moulin, courtesy of

[Images: From Vider Paris (1998-2001) by Nicolas Moulin, courtesy of

[Image: Outside-in: looking into

[Image: Outside-in: looking into  [Image: Photo by

[Image: Photo by  [Image: Photo by

[Image: Photo by

[Images: All photos, except the last five (two of which are by

[Images: All photos, except the last five (two of which are by  [Image:

[Image:  [Image:

[Image:  [Image:

[Image:  [Image: The future is not what it used to be: MIT’s

[Image: The future is not what it used to be: MIT’s  [Image: The Niagara Falls without their water, photographed by Flickr user

[Image: The Niagara Falls without their water, photographed by Flickr user  [Image: Tactical drone seed-bombing, courtesy of

[Image: Tactical drone seed-bombing, courtesy of  [Image:

[Image:  [Image: King’s Vineyard, London by Soonil Kim, via

[Image: King’s Vineyard, London by Soonil Kim, via  [Image: The “

[Image: The “ [Image:

[Image:  [Image: Rendering of the new

[Image: Rendering of the new  I’m absolutely thrilled to have curated this show, with Nicola Twilley of

I’m absolutely thrilled to have curated this show, with Nicola Twilley of  [Image: The

[Image: The  [Image: New Haven parking garage as Tornadodrome; photographed by

[Image: New Haven parking garage as Tornadodrome; photographed by  [Images: Two views inside UNStudio’s

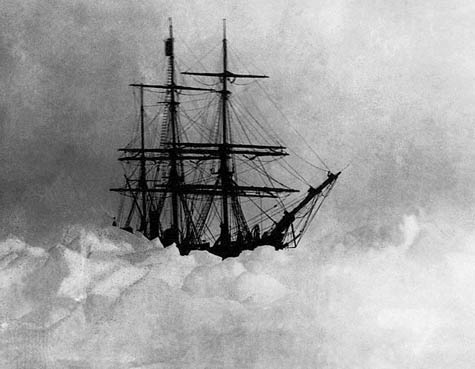

[Images: Two views inside UNStudio’s  [Image: Trapped in ice].

[Image: Trapped in ice]. [Images: Photos via

[Images: Photos via  [Image: Map of the Arctic ice routes that brought ships across the sea, courtesy of

[Image: Map of the Arctic ice routes that brought ships across the sea, courtesy of  [Image:

[Image:

[Images:

[Images:

[Image:

[Image:  [Image: From Wired Science‘s photo gallery, “

[Image: From Wired Science‘s photo gallery, “ [Image: From Wired Science‘s photo gallery, “

[Image: From Wired Science‘s photo gallery, “

[Image: From Wired Science‘s photo gallery, “

[Image: From Wired Science‘s photo gallery, “ [Image: From Wired Science‘s photo gallery, “

[Image: From Wired Science‘s photo gallery, “ [Image: From Wired Science‘s photo gallery, “

[Image: From Wired Science‘s photo gallery, “

[Images: Inside the

[Images: Inside the  [Image: Drift Station Bravo postage cancellation mark, via

[Image: Drift Station Bravo postage cancellation mark, via  [Image: Letters postmarked from Drift Station Bravo, via

[Image: Letters postmarked from Drift Station Bravo, via  [Image: A postal marking from Drift Station Bravo, via

[Image: A postal marking from Drift Station Bravo, via  [Image: A letter from Drift Station Bravo, via

[Image: A letter from Drift Station Bravo, via