[Image: Photo by Danny Lane].

[Image: Photo by Danny Lane].

Earlier this winter, I missed an opportunity to travel over to Switzerland with architects Smout Allen and Kyle Buchanan who, at the time, were leading their students around the mountain landscapes of the Alps in order to learn about infrastructures of defense and national snow-production, among other things. It sounded like an amazing trip.

[Image: Photo by Kyle Buchanan].

[Image: Photo by Kyle Buchanan].

However, I did get to see some photos sent back of the various and random things they visited in the resort city of Zermatt.

This included a huge machine known as The Snowmaker. Apparently originating in Israel, it was formerly used to cool South African diamond mines but since repurposed for spraying artificial snow onto ski slopes in the Alps.

[Images: Photos by Kyle Buchanan].

[Images: Photos by Kyle Buchanan].

The carefully choreographed operation requires a fan-like array of buried water pipes, pipes that spread throughout the resort like capillaries.

Snow—or what passes for it—then sprays out of thin, reed-like valves called “lances”—

[Image: Photo by Kyle Buchanan].

[Image: Photo by Kyle Buchanan].

—resulting in other-worldly piles of fresh white powder, perfectly sculpted domes that later require selective placement elsewhere.

[Images: Photos by Danny Lane].

[Images: Photos by Danny Lane].

The shaping of the mountain landscape—so easily mistaken for nature—exhibits obvious features of artificiality, including careful lines and striated grooves resulting from deposition, sculpting, and maintenance.

[Image: Photo by Danny Lane].

[Image: Photo by Danny Lane].

The machine is literally an oversized air-conditioning unit, waiting to be put to use by landscape-printing crews whose work is mistaken for winter. It so efficiently—though inadvertently—produced ice while cooling diamond mines in Africa that it has since been put to use 3D-printing popular tourist landscapes into existence, like something out of Dr. Seuss.

To at least some extent, The Snowmaker—and newer technology like it—has replaced older, fan-based snow machines. These thus now sit in a maintenance shed, like antique airplane engines, both derelict and obsolete.

[Image: Photo by Danny Lane].

[Image: Photo by Danny Lane].

This is all just part of the dramaturgical stagecraft of Switzerland: winter becomes a precisely choreographed thermal event that just happens to take on spatial characteristics amenable to downhill skiing.

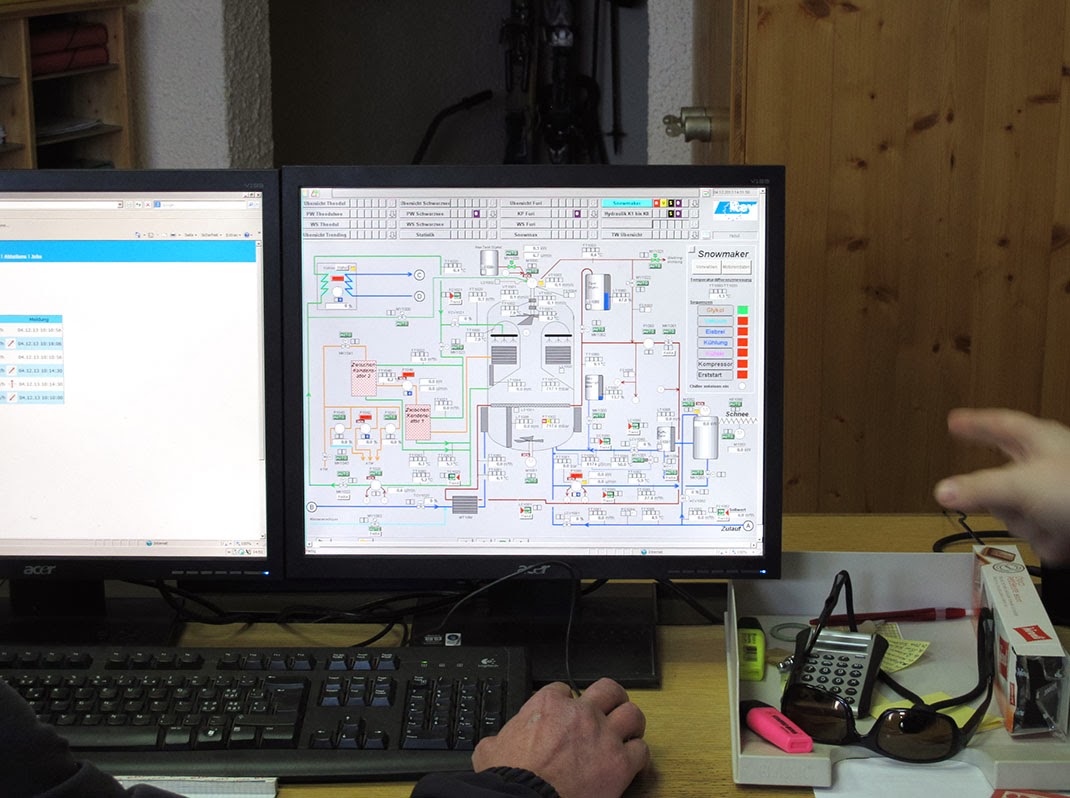

In any case, there are nearly 1,000 individual snow-production machines in Zermatt, only one of which is The Snowmaker. The whole system is controlled from a central computer, apparently operated by one wizard-like figure who is really just a stoned twentysomething in a wool hat, turning different parameters on and off and spraying whole new European landscapes into existence outside.

[Images: (top) Photo by Danny Lane; (bottom) photo by Kyle Buchanan].

[Images: (top) Photo by Danny Lane; (bottom) photo by Kyle Buchanan].

It’s like the Sorcerer’s Apprentice at the top of the world, 3D-printing recreational mountainscapes. The landscape is a computer he alone knows how to use.

Imagine if Thomas Mann’s Magic Mountain had taken place amidst a massive, artificially maintained and 3D-printed winter, and you might begin to grasp the unearthly strangeness here, the surreal mechanical goings-on at great altitude.

What appears, at first glance, to be a simple ski holiday actually turns out, upon later inspection, to be a landscape-scale encounter with artificiality and snow-based 3D-printing.

(Thanks to Mara Kanthak for her help with translation in Switzerland).

[Image: Via

[Image: Via