I am thrilled to say that I have moved east to New York City, leaving California after five unforgettable and productive years, to take on a new role as co-director, with Nicola Twilley, of Studio-X NYC at Columbia University. We both think this is an amazing opportunity to reengineer what it means to discuss cities today, and Nicola and I are committed to pursuing this goal in as wide-ranging and open a way as possible.

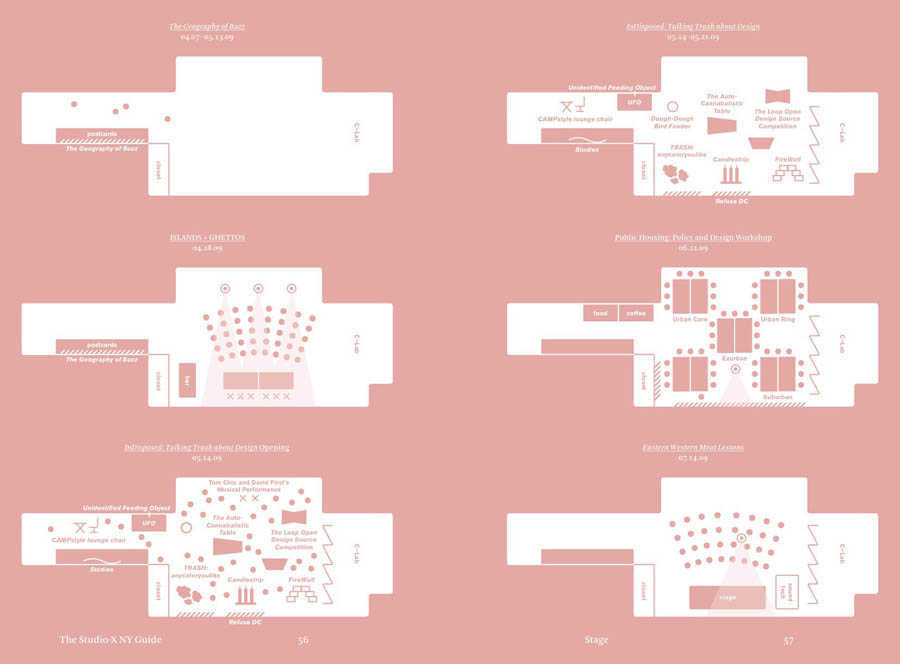

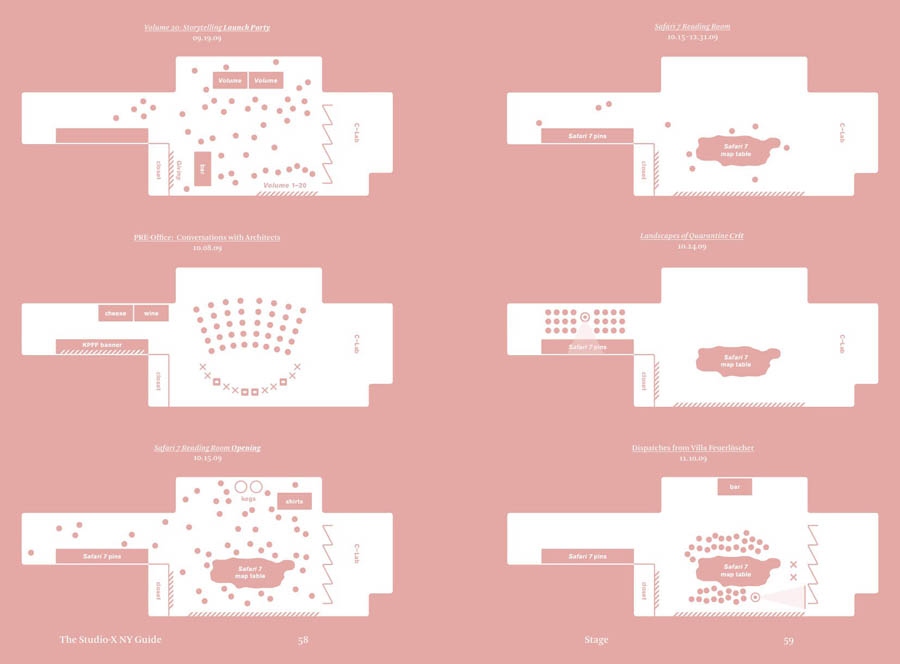

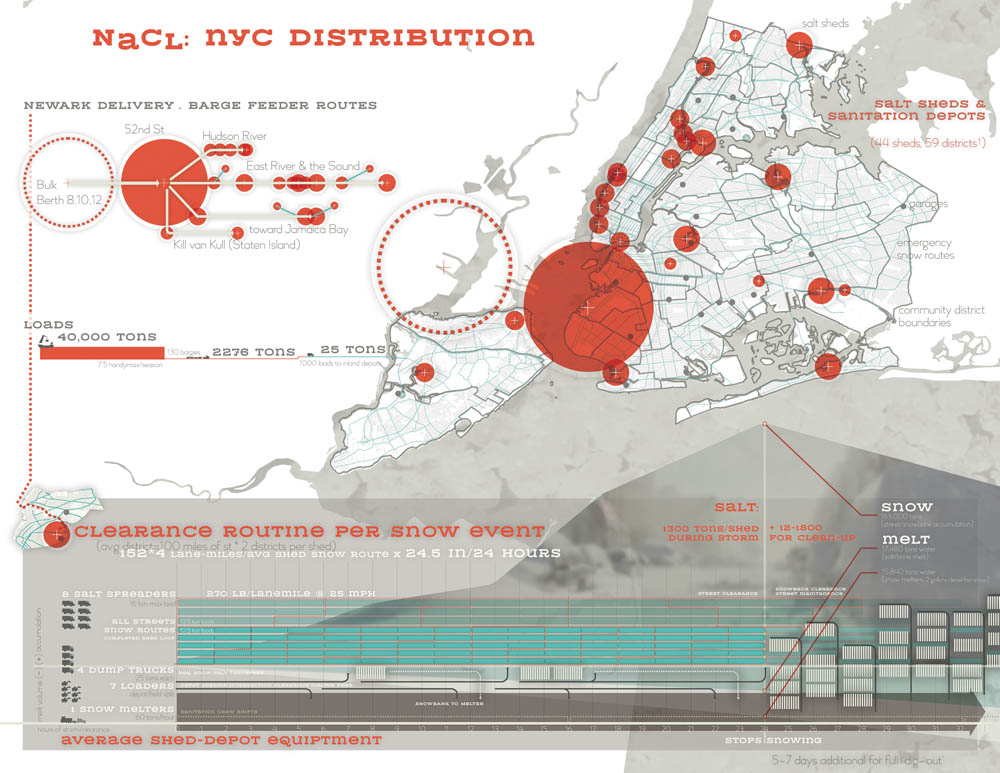

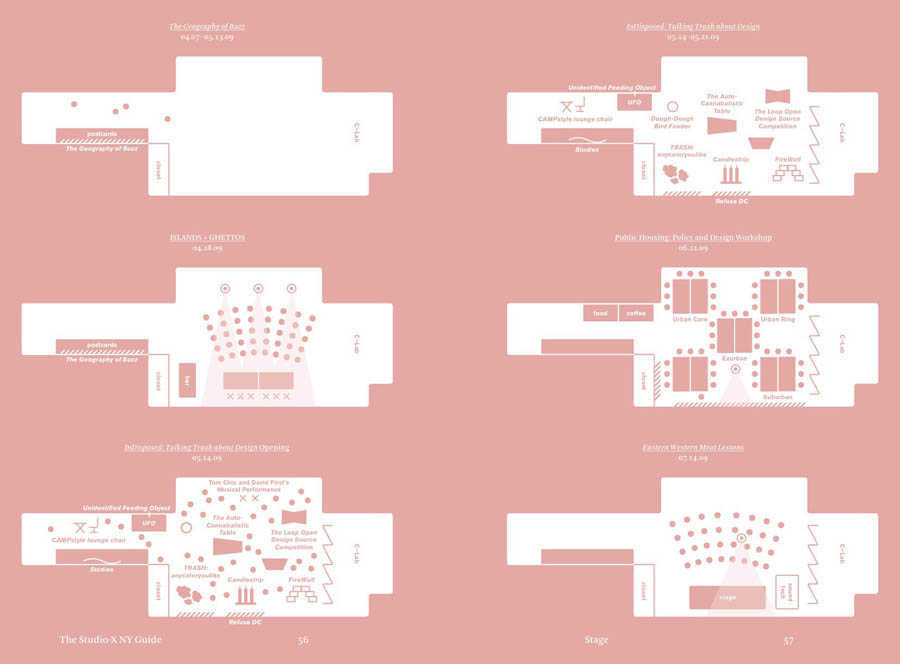

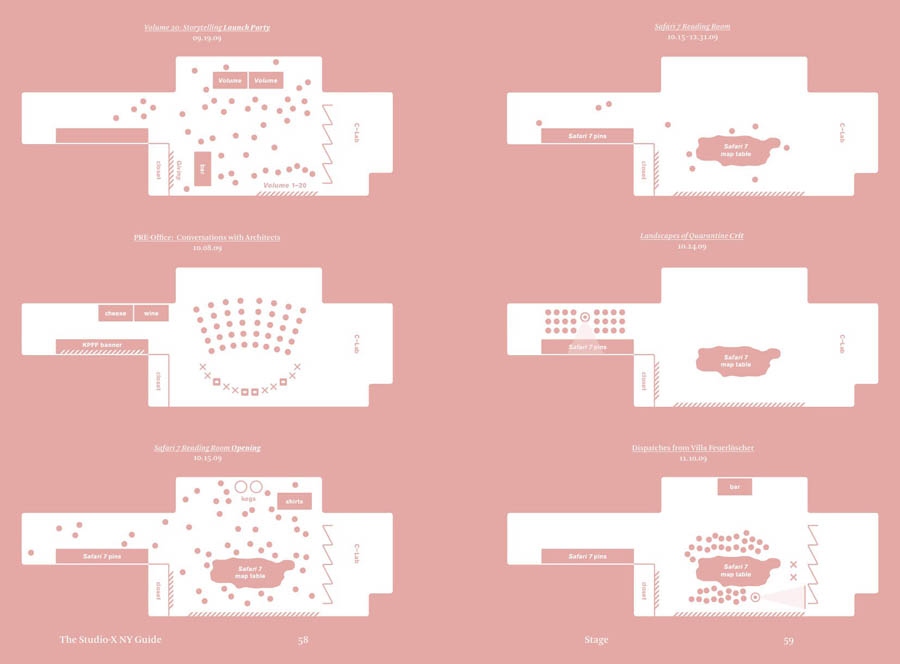

[Images: Spatial formats for events at Studio-X NYC, from Studio-X Guide to Liberating New Forms of Conversation].

[Images: Spatial formats for events at Studio-X NYC, from Studio-X Guide to Liberating New Forms of Conversation].

Speaking for both Nicola and myself, one of the most invigorating aspects of all this is the ability to work with people in radically different fields and professions—from policing to public health, archaeology to architecture, literature to film, international finance to amateur sports, subway engineers to sidewalk eccentrics, mayoral candidates to venture capitalists—all of whom have a perspective on, and vested interests in, how cities function. Nicola and I thus anticipate a surge of new collaborations, friends, and, of course, critics—and we hope to see many of you in person, at any number of our forthcoming meetings, events, exhibitions, tours, film fests, book launches, panel discussions, and more.

In the very near term, we have a few things scheduled. Kicking off a new series of conversations that we call Live Interviews @ Studio-X—or LI@SX—we will be hosting a public conversation with Deborah Estrin at 12:30pm on Thursday, September 1st.

Deborah is director of the Center for Embedded Network Sensing at UCLA. She will be discussing her work with self-monitoring applications, participatory sensing campaigns for community data projects, and citizen science, as well as larger issues of surveillance, privacy, and information filtering in the digital city.

The live interview format will take the form of an informal, one-on-one conversation—moderated in this case by Nicola Twilley—which the public is invited both to attend and to join. For those of you unable to be there in person, the LI@SX series will be recorded for posterity, webcast whenever possible, and eventually transcribed and published online.

[Images: Liam Young installs “Specimens of Unnatural History” at the Nevada Museum of Art; photos by Jamie Kingman].

[Images: Liam Young installs “Specimens of Unnatural History” at the Nevada Museum of Art; photos by Jamie Kingman].

Later that same evening—at 6pm, Thursday, September 1st—we will be hosting a Landscape Futures Night School with London-based architect Liam Young. This is an experiment with a different format: the Night School is a more interactive exploration of ideas, by definition hosted in the evenings, taking the form of everything from lectures and slideshows to design challenges and debates. The Night School series will be flexibly themed and very different each time it’s run.

Liam Young is co-founder (with Darryl Chen) of the design collective and futures think tank Tomorrows Thoughts Today, as well as leader (with Kate Davies) of the Unknown Fields Division, a nomadic design studio based at the Architectural Association (newly returned from a summer expedition to Chernobyl and Baikonur). Liam will be joining us to introduce some of his Specimens of Unnatural History, recently installed as part of the Landscape Futures exhibition at the Nevada Museum of Art in Reno.

Following Liam’s presentation of his work, I’ll be engaging with him in a public conversation, whiteboard brainstorm, and armchair journey around the world, exploring fieldwork as a form of research, the role of the sketchbook, the importance of narrative in architectural design, and the architect as investigative traveler. Expect to hear about everything from Australian kangaroo culls and the control of invasive species to conflict metals, the open-pit gold mine as designed landscape, and the difficulties of piloting a boat up the Congo.

The Landscape Futures Night School kicks off at 6:00pm; however, you must RSVP if you would like to attend: studioxnyc AT gmail DOT com.

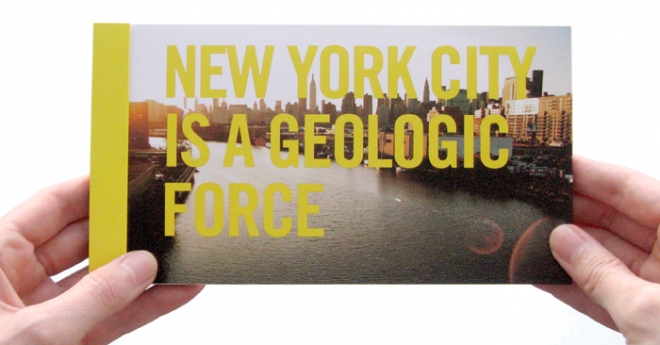

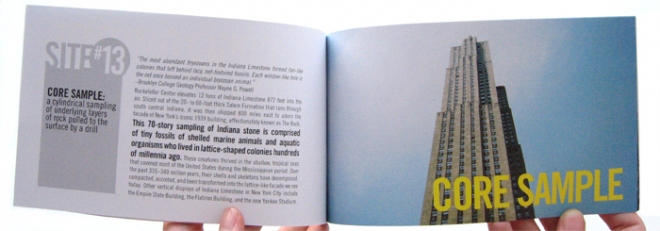

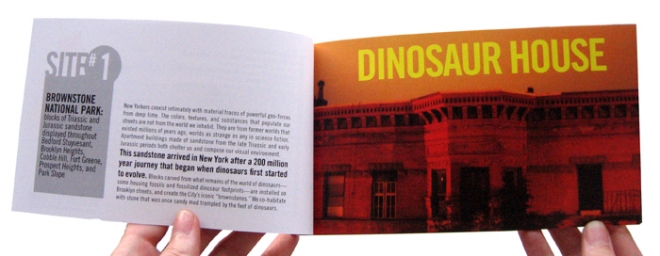

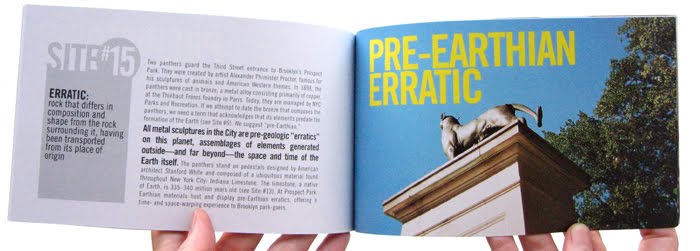

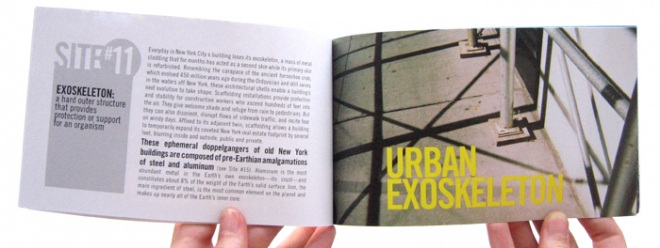

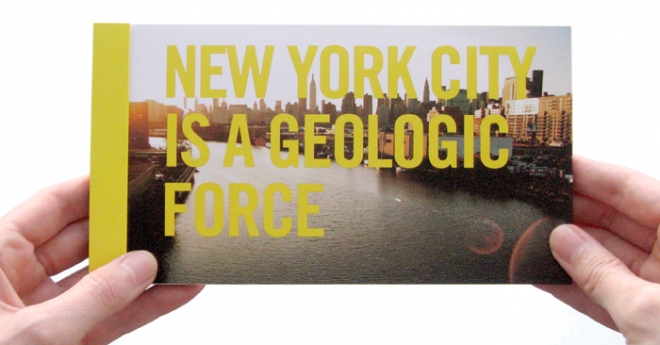

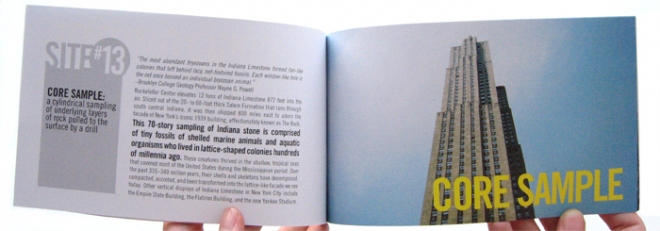

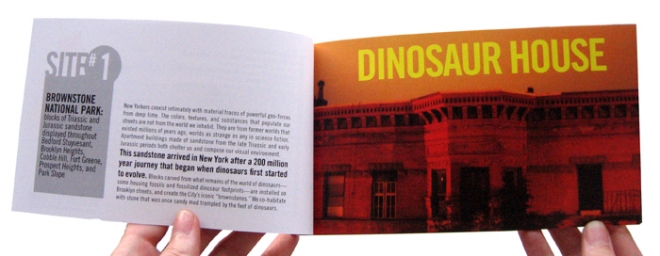

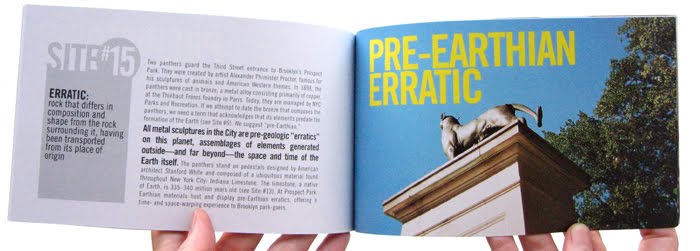

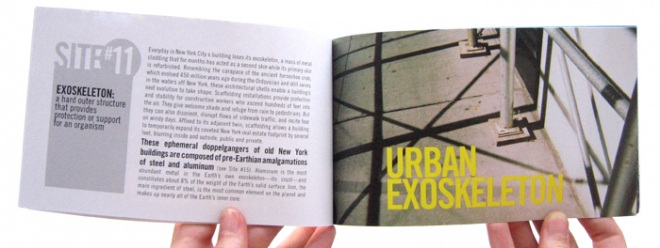

[Images: Spreads from Geologic City by Smudge Studio].

[Images: Spreads from Geologic City by Smudge Studio].

Next week, meanwhile, we will be hosting a launch party for Smudge Studio‘s new pamphlet, Geologic City, a look at the rocky underpinnings of New York, both temporary & abstract (gold reserves, fiber optics, magnetic strips on subway cards) and massively real (bedrock, landslides, urban mineralogy). Jamie Kruse and Elizabeth Ellsworth of Smudge Studio—co-authors of the blog Friends of the Pleistocene—will guide attendees through the pamphlet, as well as through the deep time of the city, utilizing Studio-X NYC’s 16th-floor windows overlooking southwestern Manhattan and the Hudson River to point out specific sites of geological influence on New York itself.

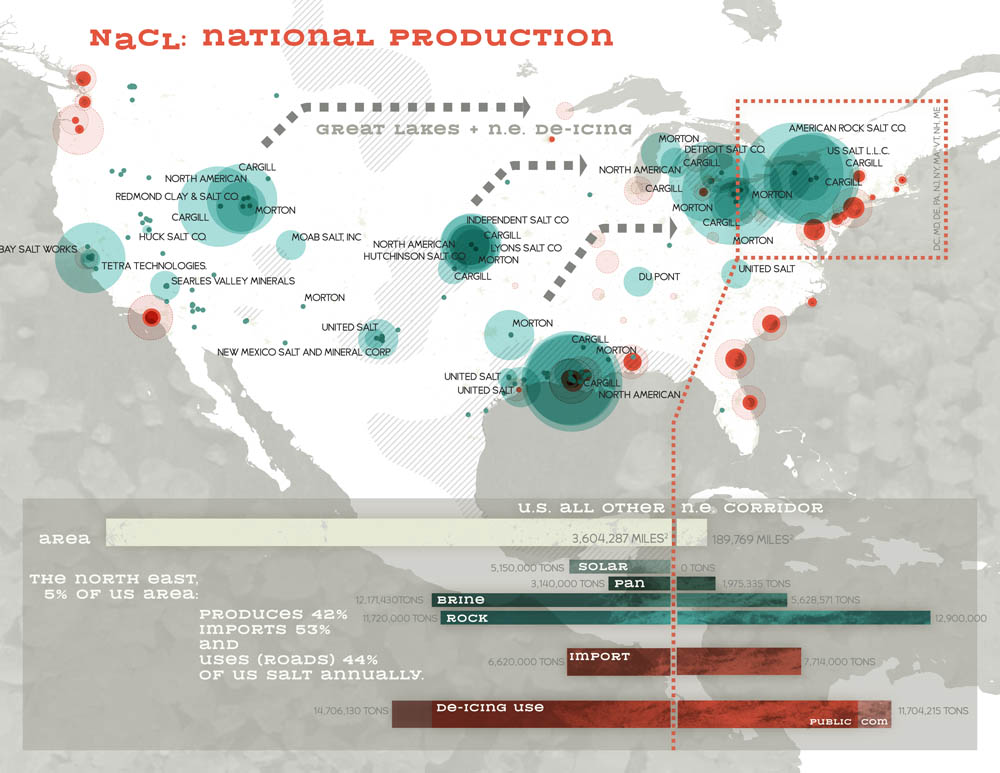

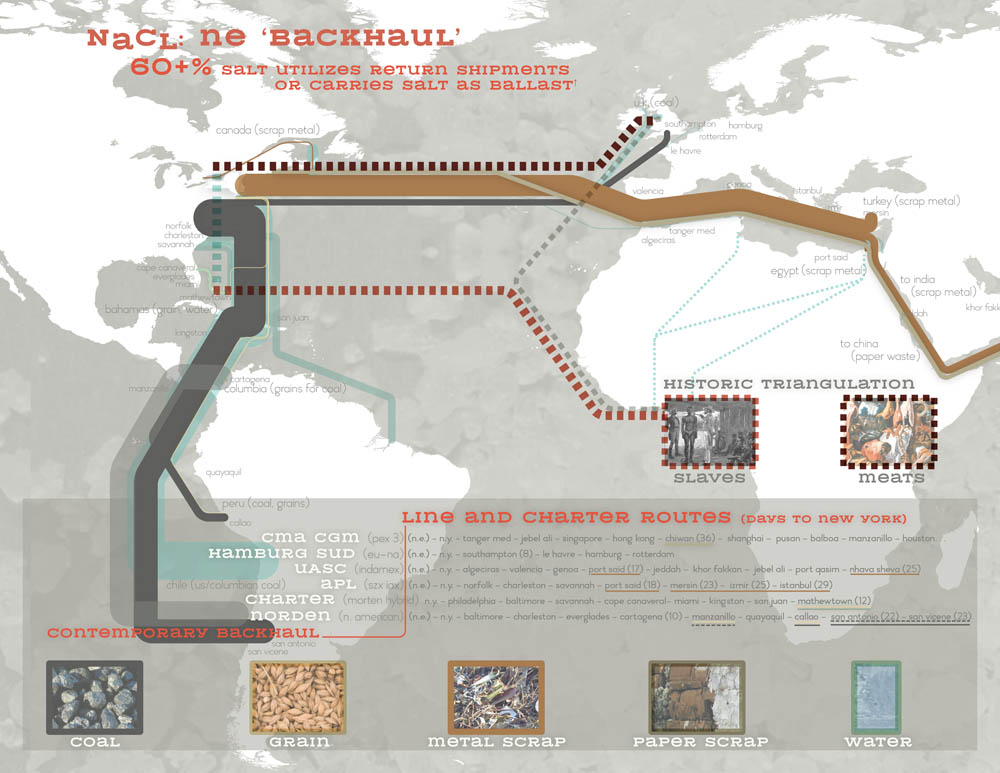

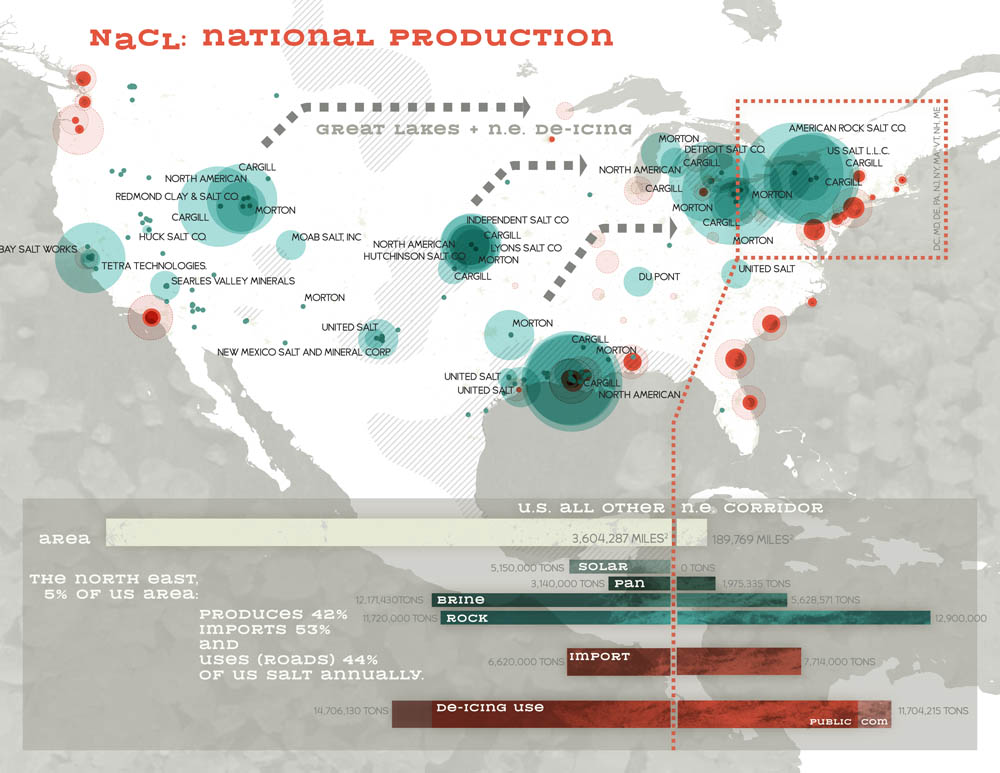

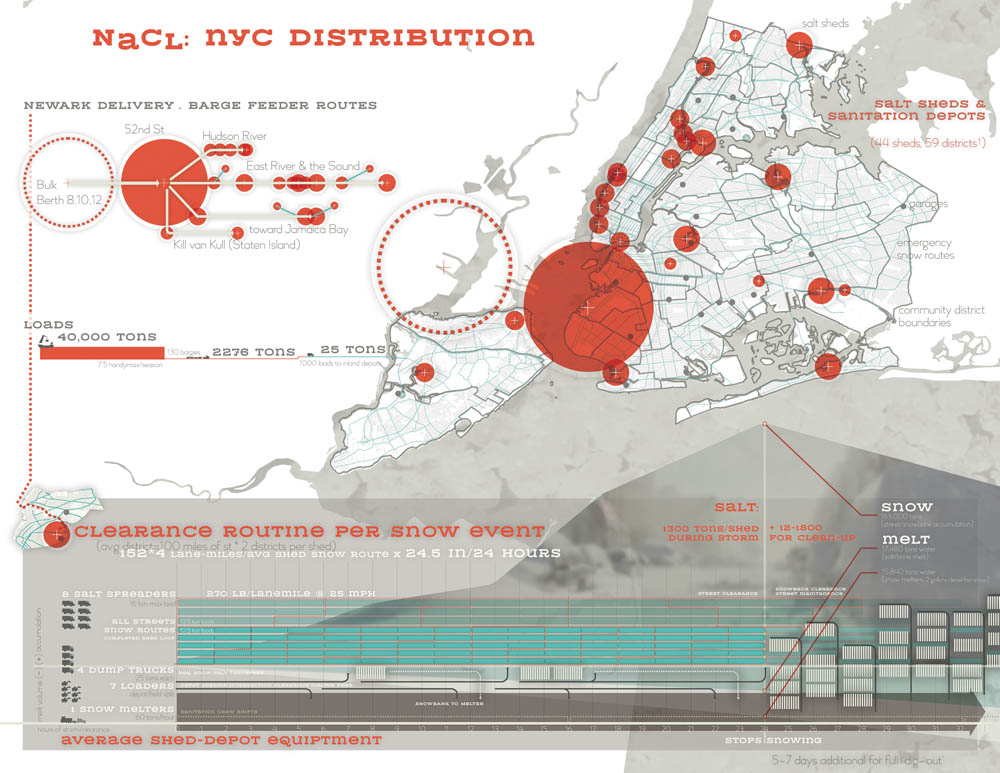

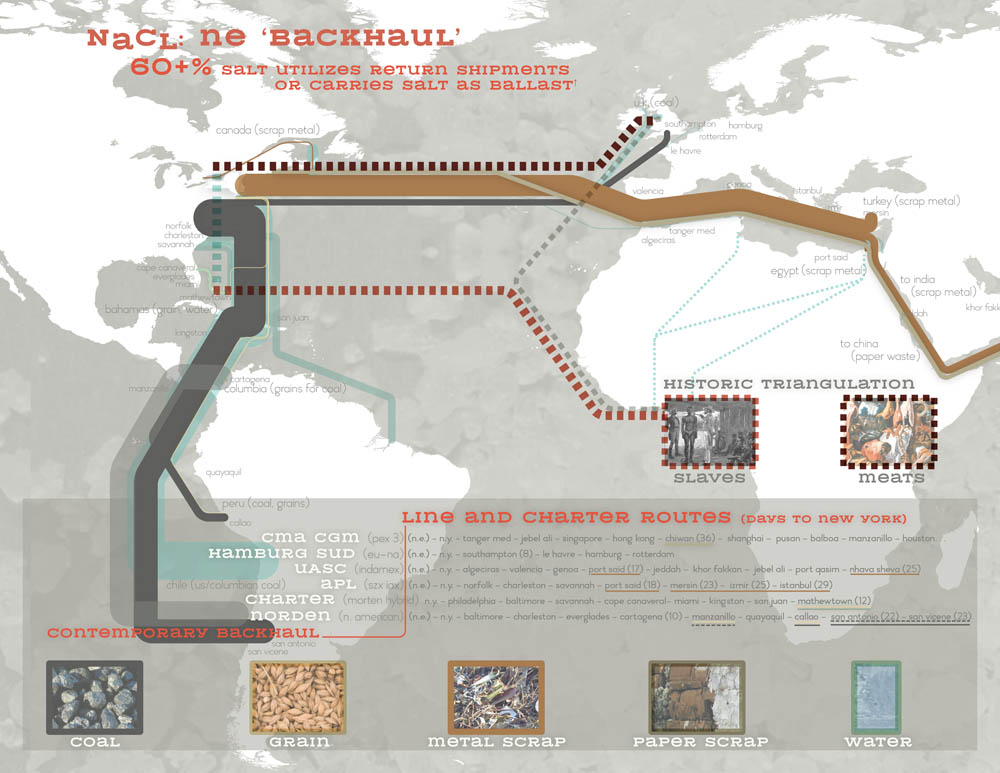

Jamie and Liz will be joined by Meg Studer, a designer and cartographer with a sustained interest in ecological systems, who has recently mapped the road-salt industry. The installations will remain in Studio-X NYC for two weeks, open to the public.

[Images: Salt maps by Meg Studer].

[Images: Salt maps by Meg Studer].

Also on our schedule for the near future is an evening with photographer Simon Norfolk, whose work should be familiar to long-term readers of this site; BLDGBLOG’s 2006 interview with Simon is still one of my personal favorites, and is well worth reading in full. Simon will be engaged in a wide-ranging discussion with Noah Shachtman—editor of Wired‘s excellent blog Danger Room—and this will kick off a longer series of events themed around conflict and the city: urban military action, urban violence, urban police technology, urban warfare, divided cities, and much more. (While he’s in town, don’t miss Simon’s lecture at the School of the Visual Arts on Wednesday, September 14).

The rest of the autumn promises a huge array of exhibitions, events, and public meetings—design charrettes, walking tours, all-day interviews, film fests, panel discussions, standalone lectures, slideshows, night schools, and more. To whet your appetite, our schedule is currently shaping up with a distributed film festival, exploring bank heists and prison breaks as architectural phenomena, co-organized with Filmmaker Magazine; a series of literary launches hosted in collaboration with GQ and Farrar, Straus and Giroux; live conversations with Benjamin Bratton, Luis Callejas, Christian Parenti, Janette Kim, Chris Woebken, and Bernard Tschumi, among many others, including ongoing collaborations with GSAPP’s own stellar faculty.

[Image: From Bridges].

[Image: From Bridges].

[Images: From Bridges].

[Images: From Bridges]. [Image: Album design by Gerco Hiddink for Bridges].

[Image: Album design by Gerco Hiddink for Bridges]. [Image: “Harmonic Bridge” by Bruce Odland and Sam Auinger, courtesy of MASS MoCA].

[Image: “Harmonic Bridge” by Bruce Odland and Sam Auinger, courtesy of MASS MoCA].

[Image: An unrelated photo by BLDGBLOG].

[Image: An unrelated photo by BLDGBLOG].

[Images: Spatial formats for events at Studio-X NYC, from

[Images: Spatial formats for events at Studio-X NYC, from

[Images: Liam Young installs “Specimens of Unnatural History” at the

[Images: Liam Young installs “Specimens of Unnatural History” at the

[Images: Spreads from

[Images: Spreads from

[Images: Salt maps by Meg Studer].

[Images: Salt maps by Meg Studer].

[Image: Via

[Image: Via

[Image: A satellite view of the corporate water feature become roadway hazard thanks to a landscaping crew in Blue Bell, Pennsylvania].

[Image: A satellite view of the corporate water feature become roadway hazard thanks to a landscaping crew in Blue Bell, Pennsylvania].

[Image: Photo by

[Image: Photo by  [Image: Photo by

[Image: Photo by  [Image: Photo by

[Image: Photo by

[Image: “

[Image: “ [Image: From “

[Image: From “ [Image: From “

[Image: From “ [Image: From “

[Image: From “

[Image: From “

[Image: From “

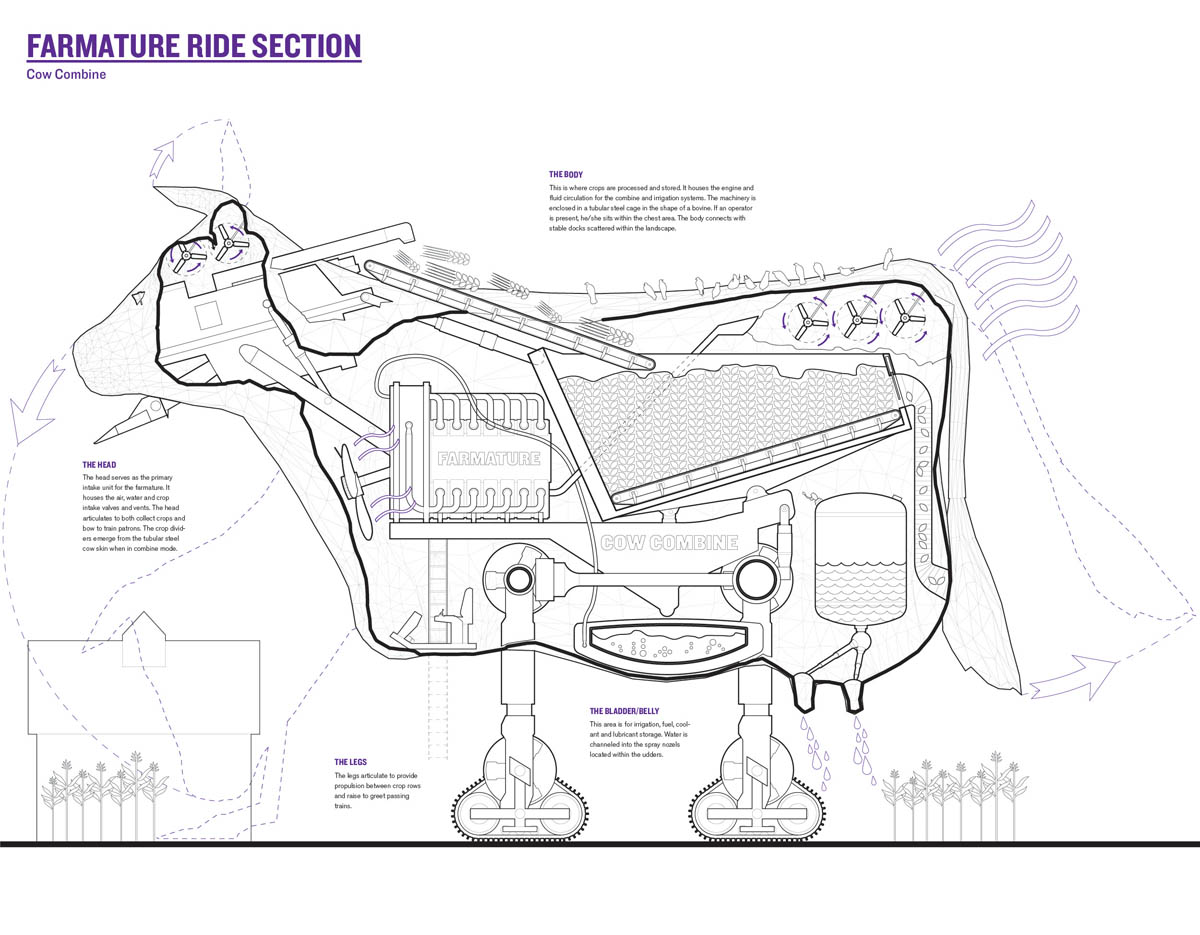

[Images: The robotic super-cows of “

[Images: The robotic super-cows of “ [Image: From “

[Image: From “

[Image: LEVEL 1 from “Theriomorphous Cyborg” by

[Image: LEVEL 1 from “Theriomorphous Cyborg” by  [Image: LEVEL 2 from “Theriomorphous Cyborg” by

[Image: LEVEL 2 from “Theriomorphous Cyborg” by  [Image: LEVELS 3-4 from “Theriomorphous Cyborg” by

[Image: LEVELS 3-4 from “Theriomorphous Cyborg” by

[Image: LEVELS 5, 6, and 7 from “Theriomorphous Cyborg” by

[Image: LEVELS 5, 6, and 7 from “Theriomorphous Cyborg” by

[Images: Two glimpses of “

[Images: Two glimpses of “

[Image: Milled terrain from “The Active Layer/Next North” by

[Image: Milled terrain from “The Active Layer/Next North” by

[Images:

[Images: