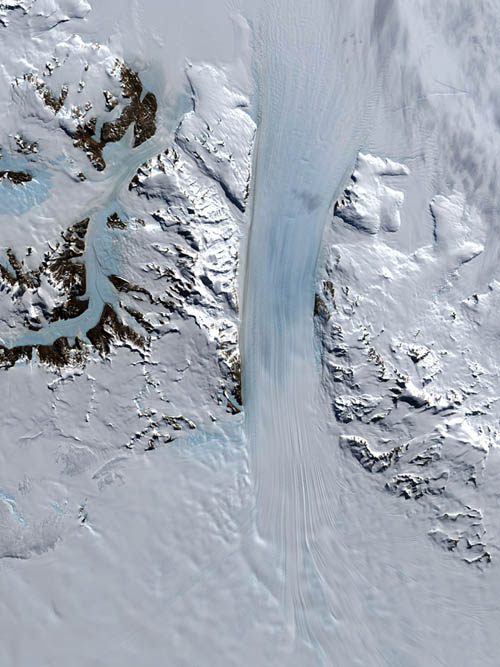

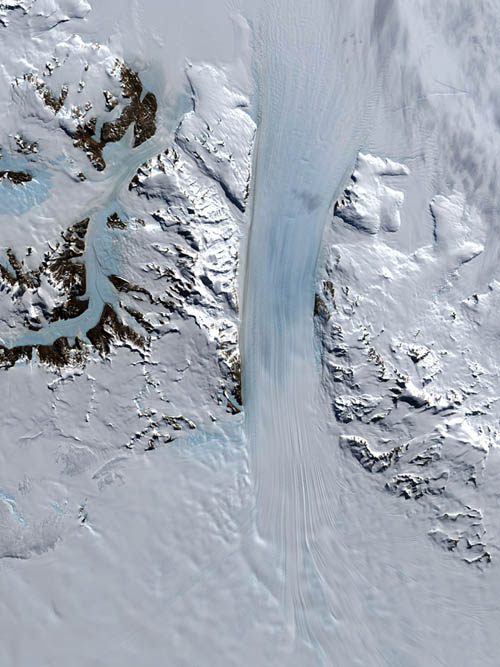

[Image: From Wired Science‘s photo gallery, “Stunning Views of Glaciers Seen From Space“].

[Image: From Wired Science‘s photo gallery, “Stunning Views of Glaciers Seen From Space“].

In light of this week’s ongoing conversation, I thought I’d take a quick look at how to build a glacier.

The “art of glacier growing,” as New Scientist calls it, is “also known as glacial grafting.” It has been “practiced for centuries in the mountains of the Hindu Kush and Karakorum ranges,” and it was never about science fiction: “It was developed as a way to improve water supplies to villages in valleys where glacial meltwater tended to run out before the end of the growing season.”

The artificial glacier, then, is simply a traditional landscape-architectural technique that manipulates and amplifies pre-existing natural processes. It is vernacular hydrology writ large.

[Image: From Wired Science‘s photo gallery, “Stunning Views of Glaciers Seen From Space“].

[Image: From Wired Science‘s photo gallery, “Stunning Views of Glaciers Seen From Space“].

So how do you build an artificial glacier?

First, you need a site, and that site should be mountainous; altitudes higher than 4,500 meters are thermally preferable. From New Scientist:

Once the site is selected, ice is brought to rocky areas where there are small boulders about 25 centimeters across. The rocks protect the ice from sunlight, and often have ice trapped in the gaps between them. This seems to be critical to a successful “planting.”

Also critical is the glacier’s “gender.” Yes, glaciers “have a gender”: “A ‘male’ glacier is one that is covered in stones and soil and moves slowly or not at all. A ‘female’ one is whiter, and grows more quickly, yielding more water.”

After [glacier-growing mountain villagers] have added female to the male ice (traditionally by importing 12 man-loads or about 300 kilograms of the stuff), they cover the area with charcoal, sawdust, wheat husk, nutshells or pieces of cloth to insulate it. Gourds of water placed among the ice and rocks are also critical to a glacier’s chances of forming, according to [artificial-glacier expert, Ingvar Tveiten]. As the glacier grows and squeezes the gourds, they burst, spreading water on the surrounding ice, which then freezes.

Awesomely, the glacier then exhibits complex internal ventilation:

Any snowmelt trapped in the budding glacier also freezes, adding more ice. Pockets of cold air moving between the rocks and ice keep the glacier cool. When the mass of rock and ice is heavy enough, it begins to creep downhill, forming a self-sustaining glacier within four years or so.

Of course, “what’s produced is hardly a glacier in the proper sense,” we’re reminded, “but growing and flowing areas of ice many tens of meters long have been reported at the sites of earlier grafts.”

Let me repeat that: to call these artificial glaciers is a poetic over-statement, as they are much more realistically described as artificially maintained deposits of snow—what I have elsewhere called non-electrical ice reserves. But the thermally self-sustaining nature of these deposits nonetheless makes them susceptible to glaciological analysis.

[Image: From Wired Science‘s photo gallery, “Stunning Views of Glaciers Seen From Space“].

[Image: From Wired Science‘s photo gallery, “Stunning Views of Glaciers Seen From Space“].

But there are also other, equally lo-fi techniques of glacier-growing.

Elsewhere, we read that “a good artificial glacier costs $50,000,” even though “the materials are simple: dirt, pipes, rocks—and runoff from real glaciers high above.” Importantly, then, but quite obviously, a controlled act of artificial glaciation can only be achieved in regions where there is already water available; you can’t simply snap your fingers and “build a glacier” in a Tucson parking lot.

In any case, this second technique “is remarkably simple”:

Water from an existing stream is diverted using iron pipes to a comparably shady part of the valley and here the water is allowed to flow out onto an inclined mountainside. At regular intervals along the slope of the mountain, small embankments of stone are made which impede the flow of water making shallow pools. At the start of winter, water is allowed to flow into this `masonry contraption’ and as the winter temperatures are constantly falling the water freezes forming a thick sheet of ice looking almost like a thin, long glacier.

All this is done before the onset of winter. During the winter, as temperatures fall steadily, the water collected in the small pools freezes. Once this cycle has been repeated over many weeks, a thick sheet of ice forms, resembling a long, thin glacier.

Again: resembling a long, thin glacier. We’re not talking about monumental, mountain-crushing tectonic formations (yet)—even if I do feel compelled to wax speculative here and suggest that, if these structures do indeed begin “to creep downhill, forming a self-sustaining glacier within four years or so,” then it is not at all unrealistic to assume that, given the right thermal circumstances and the necessary amount of snowfall, you could kick-start glaciation on a macro-scale. This might only mean on the scale of one valley—and not, say, the entire northern hemisphere—but it is an amazing idea that architects could set massive, self-sustaining, tectonically complex structures of ice into motion.

After all, glaciers are very long events, as mammoth memorably put it.

[Image: From Wired Science‘s photo gallery, “Stunning Views of Glaciers Seen From Space“].

[Image: From Wired Science‘s photo gallery, “Stunning Views of Glaciers Seen From Space“].

To reiterate the simplicity of this latter design process, I want to quote artificial-glacier expert Chawang Norphel, from an interview he did with the IPS:

Glacier melt at different altitudes is diverted to the shaded side of the hill, facing the north, where the winter sun is blocked by a ridge or a mountain slope. At the start of winter (November), the diverted water is made to flow onto the sloping hill face through appropriately designed distribution channels or outlets.

At regular intervals stone embankments are built, which impede the flow of water, making shallow pools. In the distributing chambers, 1.5-inch diameter G pipes are installed after every five feet for proper distribution of water.

Water flows in small quantities and at low velocity through the G pipes, and freezes instantly. The process of ice formation continues for three to four winter months and a huge reserve of ice accumulates on the mountain slope, aptly termed “artificial glacier.”

I emphasize this for two reasons: 1) It’s extraordinarily easy to dismiss the idea of building “artificial glaciers” simply on the basis of the phrase alone. That is, the very phrase “artificial glaciers” sounds pseudo-scientific, impossibly complex, and disastrously fossil-fuel dependent. However, it’s actually a remarkably straight-forward design process, involving thermal site-specificity and vernacular building materials. 2) The idea of “artificial glaciers” also reeks of space-operatic self-indulgence, but the fundamental purpose of these structures is to create a reliable freshwater reservoir (or ice reserve) for rural communities.

We’re not talking about nuclear-powered snow-blowers built and operated by Darth Vader, in other words; we’re talking about rural Himalayan villagers who have learned to reorganize their region’s existing snowpack so as to make it thermally self-sustaining.

Or, as Norphel himself phrases it, “Apart from solving the irrigation problem, the artificial glaciers help in the recharging of ground water and rejuvenation of springs. They enable farmers to harvest two crops in a year, help in developing pastures for cattle rearing and reducing water sharing disputes among the farmers.”

[Image: From Wired Science‘s photo gallery, “Stunning Views of Glaciers Seen From Space“].

[Image: From Wired Science‘s photo gallery, “Stunning Views of Glaciers Seen From Space“].

Having said that, the design possibilities become truly amazing when you scale this up, from a vernacular aid project to the level of carefully-maintained industrial infrastructure, and when you consider a wide range of alternative reasons for stockpiling ice (and, of course, things go bonkers if you let yourself consider genuinely and deliberately sci-fi-inflected ideas, such as maintaining artificial glaciers at the lunar south pole or using artificial glaciation as a Martian terraforming technique).

In any and all cases here, this makes artificial glaciers a fascinating topic for an architectural design studio—at least in my opinion—and the resulting conversations (and even open disagreements) about this topic have been very much worth the time already.

#glacierislandstorm

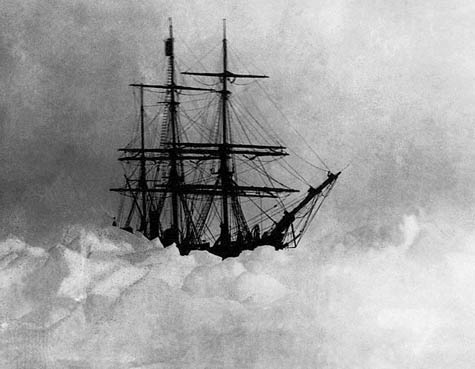

[Image: Trapped in ice].

[Image: Trapped in ice]. [Images: Photos via Jules Verne Adventures].

[Images: Photos via Jules Verne Adventures]. [Image: Map of the Arctic ice routes that brought ships across the sea, courtesy of New Scientist].

[Image: Map of the Arctic ice routes that brought ships across the sea, courtesy of New Scientist]. [Image:

[Image:

[Images:

[Images:

[Image:

[Image:  [Image: From Wired Science‘s photo gallery, “

[Image: From Wired Science‘s photo gallery, “ [Image: From Wired Science‘s photo gallery, “

[Image: From Wired Science‘s photo gallery, “

[Image: From Wired Science‘s photo gallery, “

[Image: From Wired Science‘s photo gallery, “ [Image: From Wired Science‘s photo gallery, “

[Image: From Wired Science‘s photo gallery, “ [Image: From Wired Science‘s photo gallery, “

[Image: From Wired Science‘s photo gallery, “

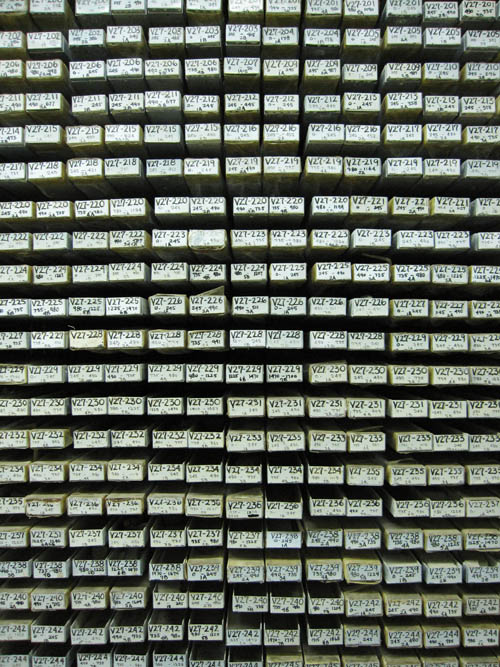

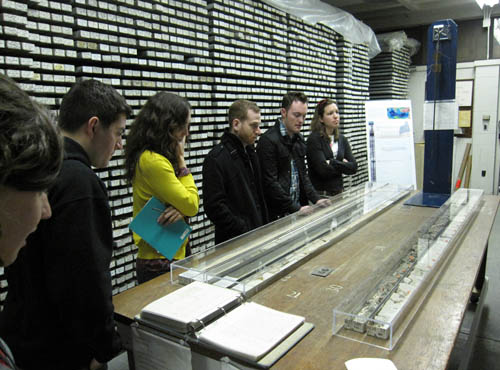

[Images: Inside the

[Images: Inside the  [Image: Drift Station Bravo postage cancellation mark, via

[Image: Drift Station Bravo postage cancellation mark, via  [Image: Letters postmarked from Drift Station Bravo, via

[Image: Letters postmarked from Drift Station Bravo, via  [Image: A postal marking from Drift Station Bravo, via

[Image: A postal marking from Drift Station Bravo, via  [Image: A letter from Drift Station Bravo, via

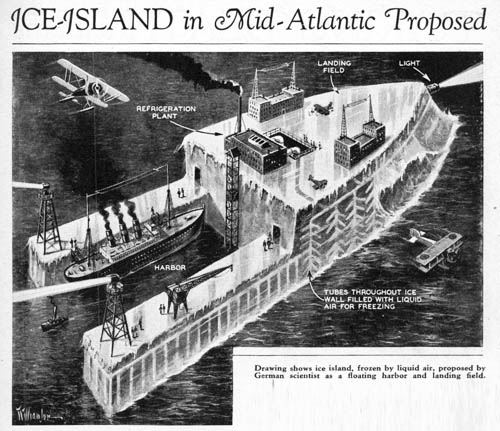

[Image: A letter from Drift Station Bravo, via  [Image: “Drawing shows ice island, frozen by liquid air, proposed by German scientist as a floating harbor and landing field”; via

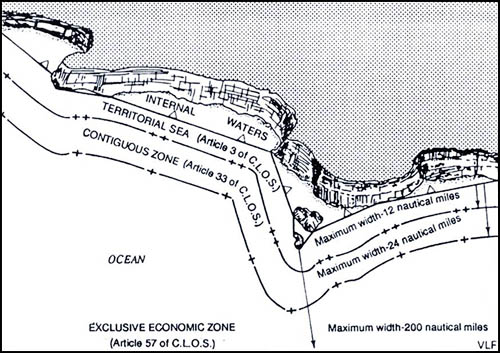

[Image: “Drawing shows ice island, frozen by liquid air, proposed by German scientist as a floating harbor and landing field”; via  [Image: Map showing a straight baseline separating internal waters from zones of maritime jurisdiction; via

[Image: Map showing a straight baseline separating internal waters from zones of maritime jurisdiction; via  [Image: Photo by Andy Marshall of

[Image: Photo by Andy Marshall of  [Image: Perseids Meteor Shower, August 11, 1999; photo by Wally Pacholka, courtesy of

[Image: Perseids Meteor Shower, August 11, 1999; photo by Wally Pacholka, courtesy of  [Image: Halley’s Comet—upper right—passes through the

[Image: Halley’s Comet—upper right—passes through the  [Image: Rock art possibly depicting a supernova. Photo by John Barentine, Apache Point Observatory, courtesy of

[Image: Rock art possibly depicting a supernova. Photo by John Barentine, Apache Point Observatory, courtesy of  [Image: Courtesy of Flickr-user

[Image: Courtesy of Flickr-user  [Image:

[Image:  [Image:

[Image:  [Image: The Okinotori Islands—or

[Image: The Okinotori Islands—or  [Image: Map of

[Image: Map of  [Image: Photo by

[Image: Photo by

[Images: Photos by

[Images: Photos by