[Image: Yucca Mountain, Nevada; courtesy of the U.S. Department of Energy].

[Image: Yucca Mountain, Nevada; courtesy of the U.S. Department of Energy].

Abraham Van Luik is a geoscientist with the U.S. Department of Energy; he is currently based at the nuclear waste-entombment site proposed for Yucca Mountain, Nevada. Yucca Mountain, a massive landform created by an extinct supervolcano inside what is now Nellis Air Force Base’s Nevada Test and Training Range, 90 miles northwest of Las Vegas, is the controversial site chosen by Congress for the storage of nuclear waste. Its political fate remains uncertain. Although the Obama Administration has stated that Yucca Mountain is “no longer… an option for storing nuclear waste,” Congress has since voted to continue funding the project—albeit only with enough funds to allow the licensing process to continue.

[Image: Resembling some new breed of Stargate emerging from the Earth, the tunnel-boring machine at Yucca Mountain reaches daylight; view larger! Courtesy of the Department of Energy].

[Image: Resembling some new breed of Stargate emerging from the Earth, the tunnel-boring machine at Yucca Mountain reaches daylight; view larger! Courtesy of the Department of Energy].

As part of our ongoing series of quarantine-themed interviews, Nicola Twilley of Edible Geography and I spoke to Van Luik about the technical nature of nuclear waste storage and what it means, on the level of geological engineering, to quarantine a hazardous material for more than one million years.

• • •BLDGBLOG: How did you start designing a project like Yucca Mountain, when you’re dealing with such enormous timescales and geological complexity?

Abraham Van Luik: You start with a question: how do you perceive the need to isolate a material from the environment?

I think most people would begin to answer that by looking at the nature of the material. Wherever that material is currently, we make sure that there is either a thick wall or a deep layer of water to protect the people working around it. That’s what’s being done at a reactor: when spent fuel comes out of a reactor, it’s taken out remotely with no one present, and put into a water basin that’s deep enough that there is no radioactive shine from the spent fuel escaping out of that water. If the pool is getting full, after five years or so of cooling, then the utility company will take the material out of the pool—remotely manipulated from behind leaded-glass windows—and put it into dry storage. Dry storage uses very thick steel and concrete. And there it will sit until someone disposes of it, or until it’s reprocessed.

Now, in most countries, what they have done next is asked: What geology would be very good for isolating this material from the environment? And what geologies are available in our country? The Swedes have gone to their granites, because their whole country is basically underlain by granites. The French looked at granites, salts, and clay, and decided to go with clay. The Belgians and Dutch are looking at clay and salts; and the Germans are looking at salts right now, but also at granites and clay. The Swiss are looking at clay, mostly, although they did look at crystalline rock—meaning rock with large crystals, like granite, gabbros, and that kind of thing. But they decided that, in their particular instance—since the Alps are still growing and slopes are not all that stable over hundreds of thousands of years—to look instead at their deep basins of clays close to the Rhine River as a repository location. We’re all looking to isolate this material for about a million years.

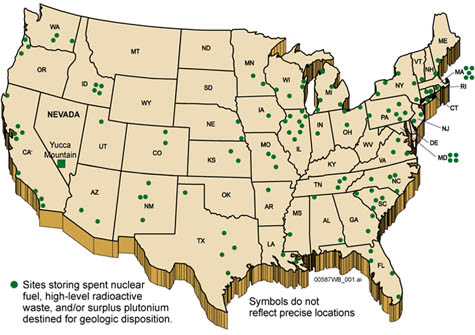

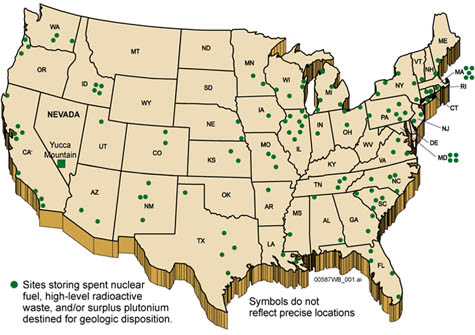

In the U.S. we did a sweep of the country, looked at all the available geologies, and we decided that we had many possible sites. We investigated some, which basically involved looking at what we knew from geological surveys of the states, and then we made a recommendation to go look at three of the possibilities in greater detail. There was then a decision process: it went from nine sites, to five, to three.

At that point, Congress stepped in. They started looking at the huge bills associated with site-specific studies—excavation is not cheap—and they said: let’s just do one site and see if it’s suitable. If it is not, then we’ll go back and see what else we can do.

So that’s how Yucca Mountain, basically, was selected. It was a cost-saving measure over the other two that were in the running for a repository. Those were a bedded salt site in Texas and a basalt site—a deep volcanic rock site—in Washington State.

But all three were looked at, and all three were judged to be equally safe for the first 10,000 years—which, at that time, was the regulation. Since the selection of Yucca Mountain, the regulation has been bumped up to a million years, which is pretty much where the rest of the world is looking: a million years of isolation.

[Images: Views inside the tunnels of Yucca Mountain; top photo by Rick Gunn for the Associated Press].

[Images: Views inside the tunnels of Yucca Mountain; top photo by Rick Gunn for the Associated Press].

Now, the reason that you want to isolate this material for a million years is that the spent fuel—meaning fuel that no longer supports the chain reaction that keeps reactors making electricity—contains actinides. These are metal elements, from 90 to 103 on the Periodic Table, most of which are heavier than uranium (which is 92). Actinides are generally very slow to radioactively decay into smaller atoms—which then decay more rapidly—and some of the actinides actually do remain hazardous for a million years and beyond. The trick is to isolate them for that length of time.

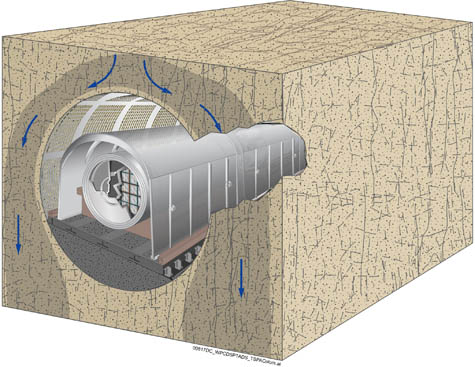

At Yucca Mountain we took the attitude that, since we basically have a dry mountain in a dry area with very little rainfall, we would use a material that can stand up to oxygen being present. The material we selected was a metal alloy called Alloy 22. Our design involves basically wrapping the stainless steel packages, in which we would receive the spent fuel, in Alloy 22 and sticking them inside this mountain with a layer of air over the top. What we know is that when water moves through rock or fractured materials, it tends to stay in the rock rather than fall—unless that rock is saturated. Yucca Mountain is unsaturated, so water ought not be a major issue for us at Yucca Mountain—yet it is.

We have to worry about future climates, because, right now in Nevada, we are in a nine year drought—and, basically since the last Ice Age, we have been in a 10,000-year drought. 80% of the time, if we look a million years into the past, we have, on average, twice the precipitation we have now. Most of the past is—and the future will be—wetter and cooler. Which is nice for Nevada! [laughs]

In any case, we tried to take advantage of the natural setting, as well as take advantage of a metal that stands up very well to oxidizing conditions. That is how, in our safety analyses, we showed that we are basically safe for well beyond a million years—if we do exactly what we said we would do in that analysis.

[Image: An engineer stands inside one of the tunnels in Yucca Mountain; courtesy of the Department of Energy].

[Image: An engineer stands inside one of the tunnels in Yucca Mountain; courtesy of the Department of Energy].

Other countries have decided not to go in a similar direction to us. The only other country that’s contemplating a similar repository to ours is Mexico. All the other countries in the world are looking at constructing something that is very deep—and under the water table. If you go under the water table deep enough, there is no oxygen in the water, and if there is no oxygen than the solubility of a sizable number of the radionuclides is a non-problem. Many are just not soluble unless there is oxygen in the water.

Going that deep then allows those countries to use a different set of materials, ones that last a long time when there is no oxygen present. For example, the Swedes are using granite—so are the Finns, by the way, and the Canadians, though the Canadians might decide to go for clays. With the granites, the older they are, the more fractured they are, and they can’t predict a million years into the future where the fracture zones are going to be. So they have chosen a copper container for their spent fuel; copper is thermodynamically stable in granite. In fact, copper deposits naturally occur in granite. They then wrap a very thick layer of bentonite clay around the container, which they put in dry. When that clay gets wet, as it will do eventually, it expands. When there is a fracture zone that is created by nature, the clay will basically decompress itself a little bit, fill the fracture zone, and you will still have a lot of protection from that clay layer. It’s a similar set up with salt or clay repositories, they eventually close up against the waste packages. Nothing moves through clay or salt very rapidly.

Those are basically the three rock types that the whole world is looking at in terms of repositories.

So you can rely more on the engineered system or more on the natural system. Either way, it’s the combination of the two systems that allows you to predict, with relative security, that you’re going to isolate a material for well over a million years. By that time, the natural decay of the material that you’ve hidden away has pretty much taken care of most of the risk. In fact, by about half a million years, most of the spent fuel is less radioactive than the ore from which it was created. That’s a wonderful argument—but the spent fuel still isn’t safe at that point. You still need to continue to isolate it, just as you don’t want to live on top of uranium ore, either. It’s a dangerous material.

In a nutshell, that’s our philosophy of containment.

[Image: Yucca Mountain diagrammed; courtesy of the Department of Energy].

[Image: Yucca Mountain diagrammed; courtesy of the Department of Energy].

BLDGBLOG: I’m interested in how you go about testing these sorts of designs. Do you actually build scale models, like the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers’ hydrological models, or do you rely on lab tests and computer simulations, given the timescale and complexity?

Van Luik: What we do is safety assessments that project safety out to a million years. What I used to say to my troops, when I was a manager of this activity, was: “Safety assessment without any underlying science is like a confession in church without a sin: without the one, you have nothing to say in the other.”

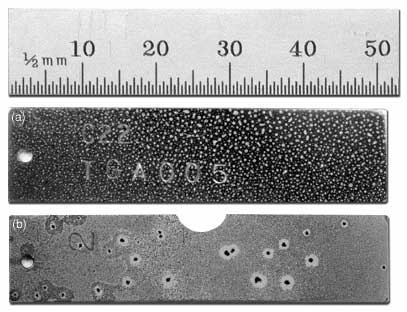

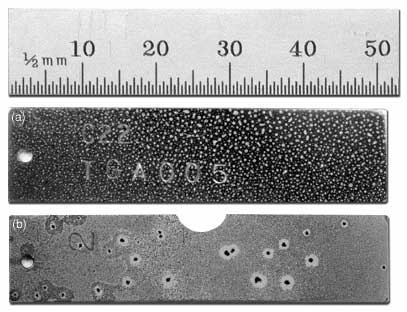

To collect the science needed to make credible projections of system safety, we have dug several miles of tunnels under this mountain; we’ve done lots of testing of how water can move through this mountain, if there was more water; and we’ve done testing of coupons of the materials that we want to use. These tests were performed using solutions, temperature ranges, and oxygen concentrations that we think are representative over the whole range of what can be reasonably expected at Yucca Mountain. Those kinds of physical tests we have done.

We have also utilized information from people who have taken spent fuel apart in some of our national laboratories and subjected it to leaching tests to see how it dissolves, how fast it dissolves, and what dissolves out of it. We have done all of that kind of testing, and that’s what forms the basis for our computer modeling.

One thing we have not done, and can’t do, is a mock-up of Yucca Mountain. It just doesn’t work that way. It’s too complicated, too large, and too long a time-scale.

[Image: Yucca Mountain, courtesy of Wikipedia].

[Image: Yucca Mountain, courtesy of Wikipedia].

In compensation for that spatial- and time-scale difficulty, what we have done is looked for similar localities with uranium deposits in them, like Peña Blanca, Mexico, just north of Chihuahua City. There, we have rock very similar to Yucca Mountain’s rock, and we have probably a 30-million year old uranium deposit—quite a rich one—that was going to be mined until the price of uranium dropped considerably. We’ve studied that piece of real estate—it has roughly similar rock, sitting under similar conditions except for more summer rainfall—and we’ve looked at the movement of radioactivity from that ore body. From that we’ve gained confidence that our computer modeling can pretty much mimic what was seen at that uranium site.

We’ve looked for natural analogues of other possible conditions—for example, the climate at Yucca Mountain during an ice age. We’ve studied six or seven sites that mimic what we would see during a climate change here.

And, in terms of materials, there are some naturally occurring materials that have a passive coating on them. We’ve studied metals found in nature that are similar in the way they act to the metals that we are using for our waste packages.

So we have gone basically all through nature looking for analogous processes—but none are exact matches for Yucca Mountain. It’s going to need something more unique than that. I think the same is true for every other repository being contemplated.

We have worked in cooperation with fourteen other countries through the European Commission’s Research Directorate in Brussels, and the Nuclear Energy Agency in Paris, to compare notes on natural analogues and discuss what is useful and what is not for which concept. All these countries are doing the same kind of thing: looking at natural occurrences that are hundreds of thousands, if not hundreds of millions, of years old.

In some cases, the natural analogues we’ve studied are billions of years old. We’ve looked at the Oklo mining district in Gabon, Africa. We studied several occurrences in that mining district where, for the last few million years, ore bodies have been subjected to oxidizing conditions, because uplift of the land brought them above the water table. We’ve looked at these natural reactor zones, which were active two billion years ago when the earth was much more radioactive than it is now, to see what we could learn about the movement of radioactivity in an oxidizing zone. We can use that data for corroborating the modeling of Yucca Mountain.

On top of all that, we have the problem of unlikely volcanic events, as well as strong earth motions from equally unlikely seismic events, at Yucca Mountain. These are problems you won’t have at most of the other repository sites being considered in the world. To study that, we brought in expert groups with their own insights and models to evaluate what the chances are, from a risk perspective, of a volcanic event actually interrupting or disrupting the repository. They also looked at the possibility of a very large ground motion adding stress and causing eventual failure of one or more of the waste packages. Although volcanic events are highly unlikely—as are very large ground-motion events—they must be factored into our analyses, based on the likelihood of their occurring over a one-million year time span.

We have basically done all safety-evaluation analyses from the perspective of the things that could happen, given the nature of this geologic setting. Looking at analogues for processes in nature has given us confidence that what we expect to see at Yucca Mountain is what we have seen nature produce elsewhere. These are indirect lines of evidence that support us—but we have also made a lot of direct measurements and observations, as well as testing in laboratories of materials and processes, to make sure that we’re on the right track.

The National Academy of Sciences has reviewed our research and our situation, and they’ve agreed that we have predictability for about a million years. That judgment influenced the EPA, who then gave us a standard for a million years.

[Image: “Coupons” of metal tested for their long-term weathering and resilience; courtesy of the Department of Energy].

[Image: “Coupons” of metal tested for their long-term weathering and resilience; courtesy of the Department of Energy].

BLDGBLOG: Could you discuss the material selection process in more detail? I’d like to hear how you found Alloy 22, for example. Also, when my wife and I visited Yucca Mountain a few years ago, we were given a black glass bead at the information center—what role does that glass play in the containment design? Finally, are the materials you’ve chosen specifically engineered for the nuclear industry, or are these simply pre-existing materials that happen to have the requisite properties for nuclear containment?

Van Luik: No, the materials are not specifically engineered for the purpose of nuclear containment.

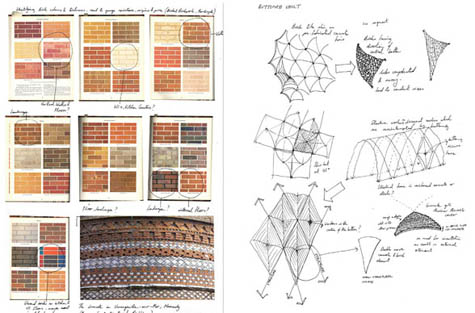

Let’s look at Alloy 22 first. We looked at the whole range of what is commercially available, in terms of pure metals and metal alloys. We also looked at things like ceramic coatings. There are some very, very hard ceramic coatings that, for example, are used on bearings for locomotives. There are also ceramics that the military uses on projectiles to penetrate buildings. There are some very good ceramic materials out there, but we had a problem with the predictability of very, very long-term behavior in ceramics. That’s why we decided to go with a metal; a metal will fail by several different corrosion mechanisms, but not by the breakage that is typical of ceramics.

One of the things that the metals industry has been doing—for the paper-pulp industry, for example, which creates the worst possible chemical environment you can imagine—is that they have been developing more and more corrosion-resistant materials. One of the top of the line of these corrosion-resistant materials was Alloy 22. We tested it alongside about six other candidates in experiments where we dripped water on them, we soaked them in water, and we had them half in and out of water, with varying solutions that we tailored for what we would expect in the mountain over time. The one that stood out—the most reliable in all of these tests—was Alloy 22.

The black glass that you saw is not something that the waste is wrapped in. This material will be made at Hanford and maybe at Idaho, too—and at Savannah River they are making that black material right now. It’s an imitation volcanic glass—a borosilicate glass—in which radioactive materials are dispersed. Material would be released from that if the waste package breaks, and if the material is touched by water or even water vapor. It would then start to alter, and as it alters it would start to release the radioactivity inside. So what you and your wife were looking at was basically a glass waste-form. We don’t make it here—that’s how radioactive waste will be delivered to us from the Defense Department and Department of Energy. We will receive it in huge containers, not as beads.

We also have little pellets of imitation spent fuel, similar to pencil lead in color, to show visitors what the fuel rods look like inside of a reactor. The fuel rods are ceramic, coated on the outside with an alloy.

[Image: Nuclear fuel rods].

[Image: Nuclear fuel rods].

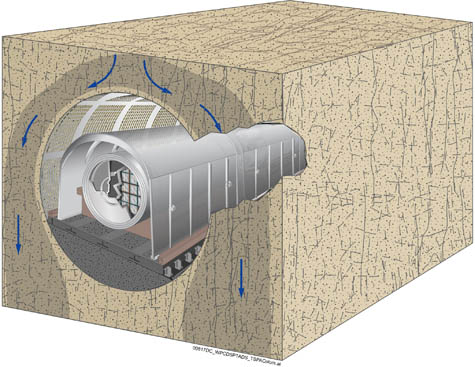

Edible Geography: Could you walk us through the planned process of loading the waste into the mountain, all the way up to the day you close the outer door?

Van Luik: Sure. The process, depending on whether Yucca Mountain ever goes through, politically speaking, will be as follows.

From the cooling pools or dry storage at the reactor, we’ve asked the nuclear utility companies to put their spent fuel—or waste—into containers that we have designed and that we will supply to them. The waste will be remotely taken out of whatever container it is in now, put into our containers, which are certified for shipping as well as disposal, and then we would slide those containers onto trains. We want to use mostly trains—we try to avoid truck use.

Rail shipping containers currently in use are massive—some approaching two-hundred tons fully loaded. The trains would bring the containers to us and then we would up-end them remotely and take the material out in a large open bay—all done remotely, again. If it comes in the shipping cask that we have provided, we will be able to put it directly into the Alloy 22 and stainless steel waste package and weld it shut. Then, with a transporter vehicle that’s also remotely operated, we would take it underground and place it end-on-end, lying down in our repository drifts. That’s what we call the tunnels; tunnels without an opening are called drifts. We would basically fill the drifts until we get to the entrance, put a door on, and then move on to the next one. That’s the basic scheme of how this would be done. Everything is shielded, of course, so that people are not exposed to radiation; workers are protected, as well as the public.

[Image: The “drifts” inside Yucca Mountain; view larger. Courtesy of the Department of Energy].

[Image: The “drifts” inside Yucca Mountain; view larger. Courtesy of the Department of Energy].

Edible Geography: How many containers could you fit inside a single drift, and how many drifts do you actually have in the mountain?

Van Luik: The drifts are each about 600 to 800 meters long. They vary a little bit, depending on where they are in the mountain. We will have 91 emplacement drifts—with an average of about 120 waste packages, set end-to-end, in each drift—to take care of the 70,000 metric tons that we are authorized to have. If we receive authorization to have more than 70,000 metric tonnes, then we’re prepared to go up to 125,000 metric tonnes of heavy metal. That metric tonnage figure doesn’t represent the total weight that goes into the mountain, by the way—it means that the containers have the equivalent of that many tonnes of uranium in them. In other words, 70,000 metric tons is about 11,000 containers that weigh about ten metric tons each, so it’s a huge amount of weight. Each container contributes a significant amount of weight in itself: the steel and the Alloy 22 are very heavy.

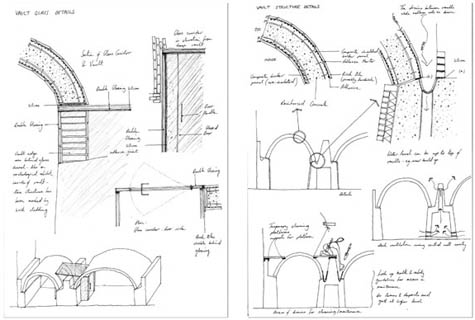

In terms of what the repository would look like, if built, it would be a series of open tunnels, one after the other, with a bridging tunnel that allows the freight to be brought in on rail. Everything is done remotely. The 40km of tunnels would all be filled up at some point, and then we would seal up the larger openings to the exterior, but leave everything else inside the mountain unsealed.

This is very different, by the way, from every other repository in the world, which would tightly compact material around the waste packages. We want to leave air around the waste packages, because of our situation. We have unsaturated water flow, rather than saturated flow, and as I’ve mentioned, water does not like to fall into air out of rock—it would rather stay in the rock, unless it’s saturated and under some degree of pressure (such as from the weight of water above it). So if we put something like bentonite clay around our packages, that would actually wick the water from the rock toward the waste packages—which is a silly thing to do if you’re trying to take advantage of an unsaturated condition.

[Image: An engineer uses ultraviolet light to analyze water-movement through rocks; courtesy of the Department of Energy].

[Image: An engineer uses ultraviolet light to analyze water-movement through rocks; courtesy of the Department of Energy].

Edible Geography: What process have you designed for sealing the exterior door? Does that also require a uniquely secure set of material and formal choices?

Van Luik: Sealing the repository wouldn’t happen for at least 100 years, so what we have done at this point is basically left that decision for the future. We have done a preliminary design, which uses a heavy concrete mixture—as well as rock rubble for a certain portion—to seal the exits from the main tunnel that goes around and feeds all the smaller tunnels.

The idea is that these openings have nothing to do with how the mountain itself functions, because the mountain is a vertical-flow system. Coming in from the sides, as we are, has nothing to do with how the water behaves in the repository, or with the containment system we’ve designed. So we just want to block the side exits and make it very difficult for someone to reenter the mountain—to the point where they would basically be much better off reentering it by drilling a whole new entryway beside one of the old ones that’s filled in.

Then there are going to be about seven vertical shafts for ventilation that will be sealed at the time of final closure. Those will be filled to mimic the hydrological properties of the rock around them; we don’t want them to become preferred pathways of water, because those will point directly into the repository.

So there are two different closure schemes for the two different types of openings: three large entryways that will be completely sealed off to prevent reentry, and seven ventilation shafts that will be filled with materials that have been engineered to mimic the hydrological properties of the rock around it.

[Image: A diagram of hypothetical water-movement around the waste packages at Yucca Mountain; courtesy of the Department of Energy].

[Image: A diagram of hypothetical water-movement around the waste packages at Yucca Mountain; courtesy of the Department of Energy].

Edible Geography: And the ventilation shafts are required because the material is so hot?

Van Luik: Yes. Once we put the waste in, we want to blow air over it by drawing in air from the bottom and blowing it out the top to take heat away until we shut off the vents for final closure. The idea is to take enough heat out of the system so that, when we close it, it doesn’t exceed our tolerances for temperature.

Edible Geography: Is there any chance that having such a large amount of heavy material at Yucca Mountain could actually pose a seismic risk for the region?

Van Luik: When we selected this particular location, we looked very carefully at faults. But you’re right: if you get beyond a certain amount of weight, as under a growing mountain range, you do start shifting things in the ground. If you build something right on a fault line you can probably change the frequency of vibration at that location, and maybe aggravate the earthquake that’s eventually going to happen.

However, even if we fill this repository to 125,000 metric tons, that is only something like .01% of the weight of the mountain itself. Plus, we are surrounded by two major faults, on both sides of the mountain, and even though there’s movement occasionally on those faults, the block in the middle—where Yucca Mountain sits—is like a boat, riding very steadily. It’s been like that for the past twelve million years, so we don’t see that it’s going to change in the future.

That said, we are in an area that’s moving all the time. The entire area now is moving slowly to the northwest, and the basin and range here is still growing—the distance between Salt Lake and Sacramento is already twice what it was twelve million years ago, and they will continue to be pulled apart. We’re well aware of the consequences of basin and range growth, and the possibility that the faults Yucca Mountain is sitting next to could be active again in the future. We factored that in. In fact, it’s those earthquakes that might actually lead to failures in the system that would allow something to come out before a million years—otherwise nothing would come out until beyond a million years.

But you can’t put enough weight in that mountain to change the tectonic regime in the area.

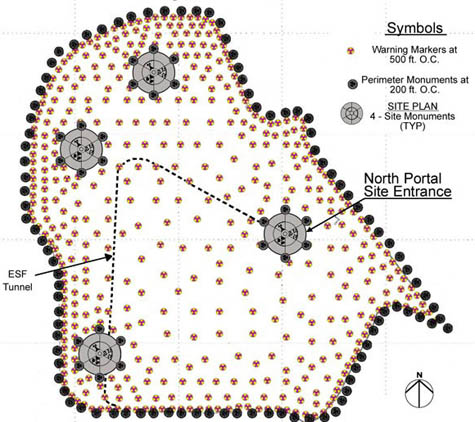

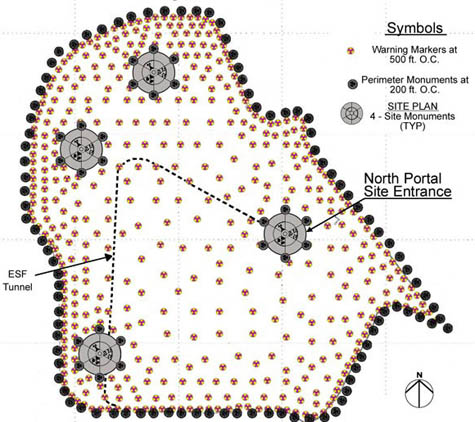

[Image: Future warning signs scattered across the Yucca Mountain site, part of “the monumental task of warning future generations“; courtesy of the Department of Energy].

[Image: Future warning signs scattered across the Yucca Mountain site, part of “the monumental task of warning future generations“; courtesy of the Department of Energy].

BLDGBLOG: Of course, once you have sealed the site, you face the challenge of keeping it away from future human contact. How does one mark this location as a place precisely not to come to, for very distant future generations?

Van Luik: We have looked very closely at what WIPP is doing—the Waste Isolation Pilot Plant in New Mexico. They did a study with futurists and other people—sociologists and language specialists. They decided to come up with markers in seven languages, basically like a Rosetta Stone, with the idea that there will always be someone in the world who studies ancient languages, even 10,000 years from now, someone who will be able to resurrect what the meanings of these stelae are. They will basically say, “This is not a place of honor, don’t dig here, this is not good material,” etc.

What we have done is adapt that scheme to Yucca Mountain—but we have a different configuration. WIPP is on a flat surface, and their repository is very deep underground; we’re basically inside a mountain with no resources that anybody would want to go after. We will build large marker monuments, and also engrave these same types of warnings onto smaller pieces of rock and metal, and spread them around the area. When people pick them up, they will think, “Oh—let’s not go underground here.”

Now if people see these things and decide to go underground anyway, that becomes advertent, not inadvertent, intrusion—and we can’t protect against that, because there’s no way to control the future. All we’re worried about is warning people so that, if they do take some action that’s not in their best interest, they do so in the full knowledge of what they’re getting into. The markers that we’re trying to make will be massive, and they will be made of materials that will last a long time—but they’re just at the preliminary stage right now.

What I have been lobbying for with the international agencies, like the International Atomic Energy Agency and the Nuclear Energy Agency is that before anybody builds a repository, let’s have world agreement on the basics of a marker system for everybody. Whoever runs the future, tens of thousands of years from now, shouldn’t have to dig up one repository and see a completely different marker system somewhere else and then dig that up, too. They should be able to learn from one not to go to the others.

Of course, there’s also a little bit of fun involved here: what is the dominant species going to be in 10,000 years? And can you really mark something for a million years?

What we have looked at, basically, is marking things for at least 10,000 years—and hopefully it will last even longer. And if this information is important to whatever societies are around at that time, if they have any intelligence at all, they will renew these monuments.

[Image: Aerial view of Yucca Mountain; courtesy of the Department of Energy].

[Image: Aerial view of Yucca Mountain; courtesy of the Department of Energy].

BLDGBLOG: What kinds of projects might you work on after Yucca Mountain? In other words, could you apply your skills and a similar design process to different containment projects, such as carbon sequestration?

Van Luik: I think so—if we ever get serious about carbon sequestration. I don’t know if you know this, but we laid off a lot of people here because there were budget cuts, and many of those people, because of the experience they had with modeling underground processes, are now working on carbon sequestration schemes for the energy sector and the Department of Energy.

No matter what happens to Yucca Mountain—whether it goes through or not—dealing with spent fuel and other nuclear waste will still be a problem, and that’s the charter that was given to our office. What I’m hoping is that, as soon as Yucca Mountain gets completely killed or gets the go-ahead, I can go back to what I loved doing in the past, which was to look at selecting sites for future repositories.

One repository won’t be enough for all time; it will be enough for maybe a hundred years, at the very most. You have to plan ahead. As long as you create the nuclear waste, you need to have a place to put it. Even if you reprocess it—even if you build fast reactors and basically burn the actinides into fission products so that they only have to be isolated for 500 years rather than a million—you still have to have a place to put that material. Even if we can build repositories less and less frequently, we will still be creating waste that needs to be isolated from the environment.

BLDGBLOG: You mentioned that your favorite pastime was looking for repository sites. If you had the pick of the earth, is there a location that you genuinely think is perfect for these types of repositories, and where might that location be?

Van Luik: My ideal repository location has changed over time. When I worked on crystalline rock, like granites, I thought crystalline rock was the cat’s meow. When I worked for a short time in salt, I thought salt was the perfect medium. Now that I have worked with the European countries and Japan for the past twenty-five years, learning of their studies of various repository locations, I’m beginning to think that claystone is probably the ideal medium.

In the U.S., I would go either to North or South Dakota and look for the Pierre Shale, where it grades into clay: there, you get the best of both worlds. I have been quoted by MSNBC, much to the chagrin of my bosses, saying that, if I were to get the pick of where we go next, that’s where I would go. They really didn’t like that—I was supposed to praise the Yucca Mountain site. But let’s get real: Yucca Mountain was chosen by Congress. We have shown that it’s safe, if we do what we say in terms of the engineered system. But it was not chosen to be the most optimal of all optimal sites, the site-comparison approach was taken off the table by Congress. As long as a chosen site and its system are safe, however, that is good enough.

Our predicted performance for Yucca Mountain, lined up to what the French are projecting for their repository in clay, and next to what the Swedes are projecting for their repository in granite, shows about the same outcome, over a million years, in terms of potential doses to a hypothetical individual. We’re safe as anybody can be—which is what our charter requires. We told Congress in 2002 that, yes, it can it be done safely here—but it’s going to cost you, and that cost is in Alloy 22 and stainless steel. Congress said OK and it became public law.

[Image: Map of repository sites across the United States; courtesy of the Department of Energy].

[Image: Map of repository sites across the United States; courtesy of the Department of Energy].

Edible Geography: Are any countries actually using their repositories yet?

Van Luik: They’re getting very close to licensing in Finland and Sweden. Those are going to be the first two. We have a firm site selection in France, which means that they’ll be going into licensing soon. Licensing takes several years in every country. In fact, we’re in licensing now, except we had a change of administration and they’ve decided that they really don’t want to do Yucca Mountain anymore. They want to do something else. They have every right to make those kind of policy decisions—so here we are.

No one is actually loading high-level waste or spent nuclear fuel into a repository yet. We have our own repository working with transuranic waste from the Defense program, in New Mexico, and both the Swedes and the Finns have medium-level waste sites, which are basically geological disposal sites, that have been active for over a decade.

The Swedes and Finns have a lot of experience building repositories underground, and their situation is interesting. The Swedes are building a repository under the Baltic Sea, but in granites that they can get to from dry land. When there is a future climate change, however, there’s going to be a period when the repository area will be farmable; it will be former ocean-bottom that is now on the surface. Their scenario is that, at the end of the next ice age, you might actually get a farmer who drills a water-well right above the repository.

The Finns actually have a very pragmatic attitude to this. They have regulations that basically cover the entire future span, out to a very long time period—but they also say that, once the ice has built up again and covered Finland, it won’t be Finland. No one will live there. But it doesn’t matter whether anyone lives there or not: you still have to provide a system that’s safe for whoever’s going to be there when the ice retreats.

We—as in the whole world—need to take these future scenarios quite seriously. And these are very interesting things to think about—things that, in normal industrial practice, you never even consider.

The repository program in England, meanwhile, went belly-up—because of regulatory issues, mostly—but it’s coming back, and it’s probably going to come back to exactly the same place as it was before. That’s a sedimentary-metamorphosed hard-rock rock site at Sellafield, right by the production facility. No transportation will be involved, to speak of. That’s not a bad idea, but they had to prove that the rock was good. The planning authority rejected their proposal the first time, so they dissolved the whole waste management company and now the government is going to take over the project; it’s not going to be private anymore. In the end, the government takes over this kind of stuff in most places because the long-term implications go way beyond the lifetime of one corporation.

If there’s any country that’s setting a good example for waste disposal, it’s Germany. They’re the only country I know of who have the same kind of regulations for hazardous waste and chemical waste as they do for nuclear waste. There are two or three working geological repositories for chemical waste in Germany, and they have been working for a very long time. They’re the only ones in the world. The chemical industry in the U.S. has basically said, no, no, don’t go there! [laughs]

[Images: Like a scene from Poe’s “Cask of Amontillado“—as rewritten by the international chemical industry—hazardous materials undergo geological entombment].

[Images: Like a scene from Poe’s “Cask of Amontillado“—as rewritten by the international chemical industry—hazardous materials undergo geological entombment].

But I think Germany is right: if one thing needs to be isolated because it’s dangerous, then the other thing—that never decays and is also dangerous—needs to be treated in the same way. The EPA does have a standard for deep-well injection of hazardous waste—they have a 10,000-year requirement for no return to the surface. That was comparable to what we had here, until the standard for Yucca Mountain got bumped up to a million years by Congress. But with some chemicals, regulations only require a few hundred years of isolation—that’s all. Those things don’t decay, so that doesn’t make sense to me.

Anyway, I applaud Germany for their gumption—and they’re very dependent on their chemical industry for income. It’s not like they’re trying to torpedo their industry. They’re just saying: you have to do this right.

• • •This autumn in New York City,

Edible Geography and BLDGBLOG have teamed up to lead an 8-week

design studio focusing on the spatial implications of quarantine; you can read more about it

here. For our studio participants, we have been assembling a coursepack full of original content and interviews—but we decided that we should make this material available to everyone so that even those people who are not in New York City, and not enrolled in the quarantine studio, can follow along, offer commentary, and even be inspired to pursue projects of their own.

For other interviews in our quarantine series, check out Isolation or Quarantine: An Interview with Dr. Georges Benjamin, Extraordinary Engineering Controls: An Interview with Jonathan Richmond, On the Other Side of Arrival: An Interview with David Barnes, The Last Town on Earth: An Interview with Thomas Mullen, and Biology at the Border: An Interview with Alison Bashford.

More interviews are forthcoming.

[Image: The Sutro Cliff House, San Francisco].

[Image: The Sutro Cliff House, San Francisco]. [Image:

[Image:  [Image: Resembling some new breed of

[Image: Resembling some new breed of  [Images: Views inside the tunnels of

[Images: Views inside the tunnels of  [Image: An engineer stands inside one of the tunnels in Yucca Mountain; courtesy of the

[Image: An engineer stands inside one of the tunnels in Yucca Mountain; courtesy of the  [Image: Yucca Mountain diagrammed; courtesy of the

[Image: Yucca Mountain diagrammed; courtesy of the  [Image:

[Image:  [Image: “Coupons” of metal tested for their long-term weathering and resilience; courtesy of the

[Image: “Coupons” of metal tested for their long-term weathering and resilience; courtesy of the  [Image: Nuclear fuel rods].

[Image: Nuclear fuel rods]. [Image: The “drifts” inside Yucca Mountain;

[Image: The “drifts” inside Yucca Mountain;  [Image: An engineer uses ultraviolet light to analyze water-movement through rocks; courtesy of the

[Image: An engineer uses ultraviolet light to analyze water-movement through rocks; courtesy of the  [Image: A diagram of hypothetical water-movement around the waste packages at Yucca Mountain; courtesy of the

[Image: A diagram of hypothetical water-movement around the waste packages at Yucca Mountain; courtesy of the  [Image: Future warning signs scattered across the Yucca Mountain site, part of “the

[Image: Future warning signs scattered across the Yucca Mountain site, part of “the  [Image: Aerial view of

[Image: Aerial view of  [Image: Map of repository sites across the United States; courtesy of the

[Image: Map of repository sites across the United States; courtesy of the  [Images: Like a scene from Poe’s “

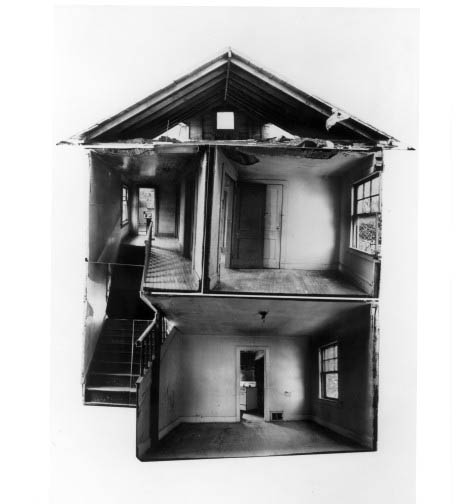

[Images: Like a scene from Poe’s “ [Image: A photo-collage from Splitting by Gordon Matta-Clark].

[Image: A photo-collage from Splitting by Gordon Matta-Clark]. [Image: “Moravian Mount” from

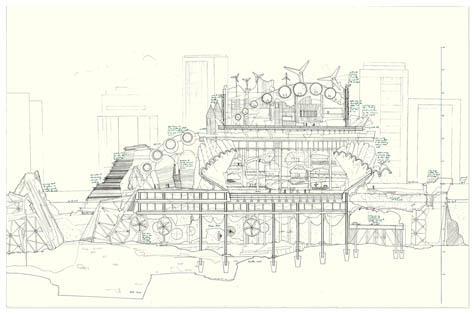

[Image: “Moravian Mount” from

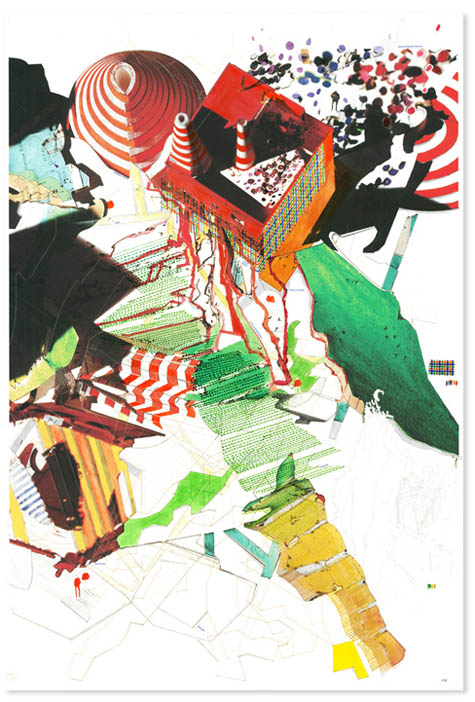

[Images: From

[Images: From  [Image: From

[Image: From

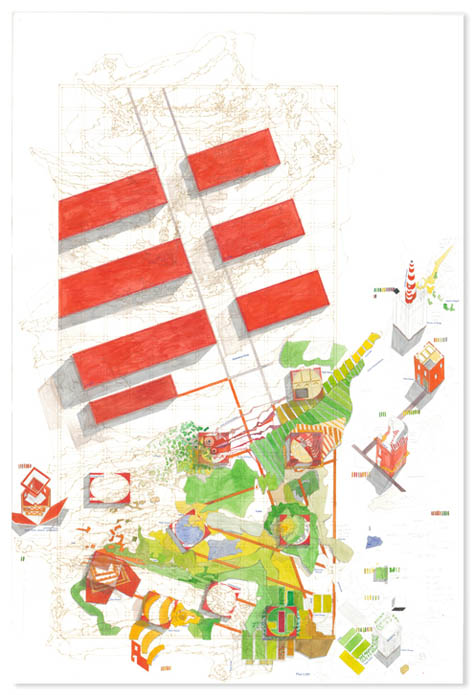

[Images: From

[Images: From

[Images: “House of Drink,” “Greenhouse,” and town plan from

[Images: “House of Drink,” “Greenhouse,” and town plan from

[Image: From

[Image: From

[Images: From

[Images: From

[Images: From

[Images: From  [Image: Michael Light, Bingham Pit photograph mounted and on display].

[Image: Michael Light, Bingham Pit photograph mounted and on display]. [Image: Two photos from

[Image: Two photos from  [Image: Michael Light, “Garfield Stack, Oquirrh Mountains and Ancient Beach of Great Salt Lake” (2006)].

[Image: Michael Light, “Garfield Stack, Oquirrh Mountains and Ancient Beach of Great Salt Lake” (2006)]. [Image: “Oops” by

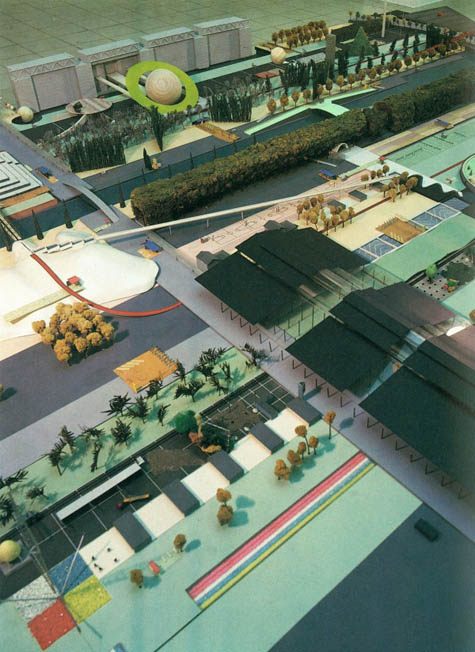

[Image: “Oops” by  [Image: From Rem Koolhaas’s unbuilt proposal for the Parc de la Villette in Paris, via

[Image: From Rem Koolhaas’s unbuilt proposal for the Parc de la Villette in Paris, via  [Image: From a project by

[Image: From a project by  [Image: An emergency hospital ward in Kansas during the 1918 flu].

[Image: An emergency hospital ward in Kansas during the 1918 flu]. [Image:

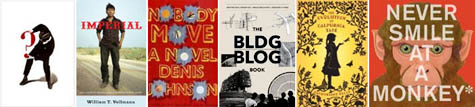

[Image:  [Image: Sample covers of the

[Image: Sample covers of the  [Images: Hong Kong’s entire Metro Park Hotel was put under quarantine for seven days after an H1N1-positive Mexican tourist stayed there in May 2009; “psychologists were on standby,” we read. All photos courtesy of the

[Images: Hong Kong’s entire Metro Park Hotel was put under quarantine for seven days after an H1N1-positive Mexican tourist stayed there in May 2009; “psychologists were on standby,” we read. All photos courtesy of the  [Images: (left) Reporter

[Images: (left) Reporter  [Images: Shuhei Endo’s “tennis dome/emergency center” (left), photographed by Kenichi Amano, next to the New Orleans Superdome, post-Katrina].

[Images: Shuhei Endo’s “tennis dome/emergency center” (left), photographed by Kenichi Amano, next to the New Orleans Superdome, post-Katrina]. [Image:

[Image:  [Image: Six of Amazon.com’s

[Image: Six of Amazon.com’s  [Image: The cooling towers of the

[Image: The cooling towers of the