For his final student project presented last month at Rice University, Viktor Ramos produced The Continuous Enclave: Strategies in Bypass Urbanism.

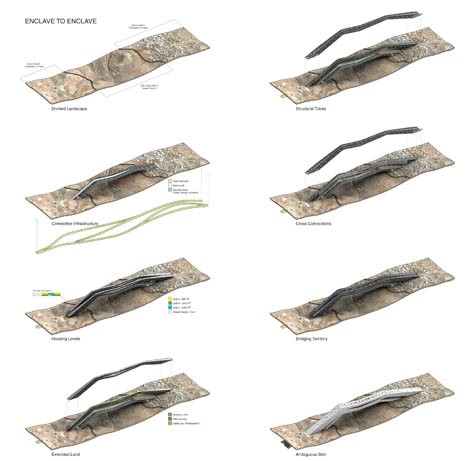

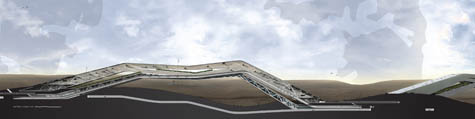

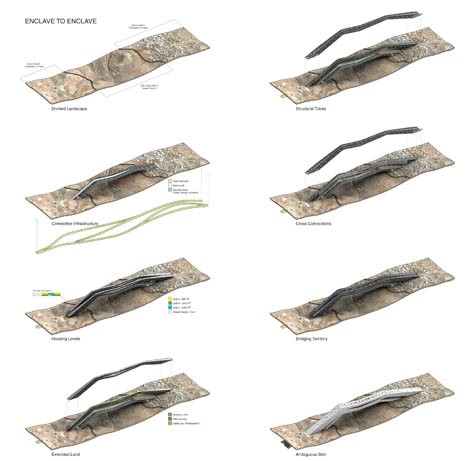

[Image: From The Continuous Enclave: Strategies in Bypass Urbanism by Viktor Ramos; view larger].

[Image: From The Continuous Enclave: Strategies in Bypass Urbanism by Viktor Ramos; view larger].

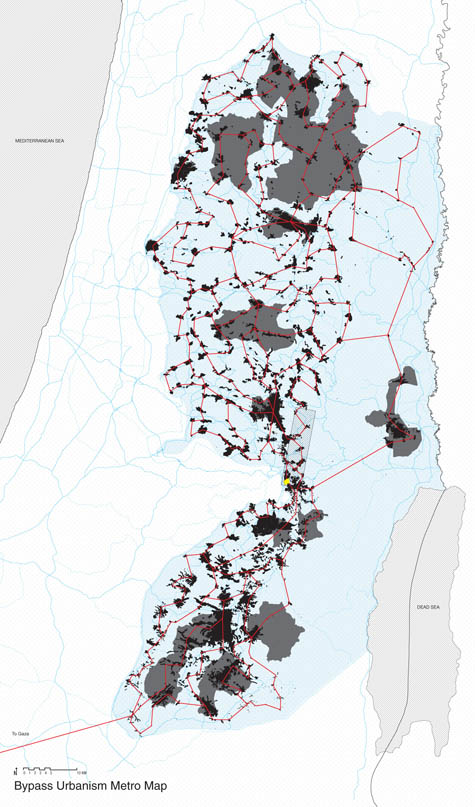

The project explores how new forms of habitable infrastructure might be extrapolated from a geopolitical agreement – in this case, materializing architectural form from the legal interstices of the Oslo Accords.

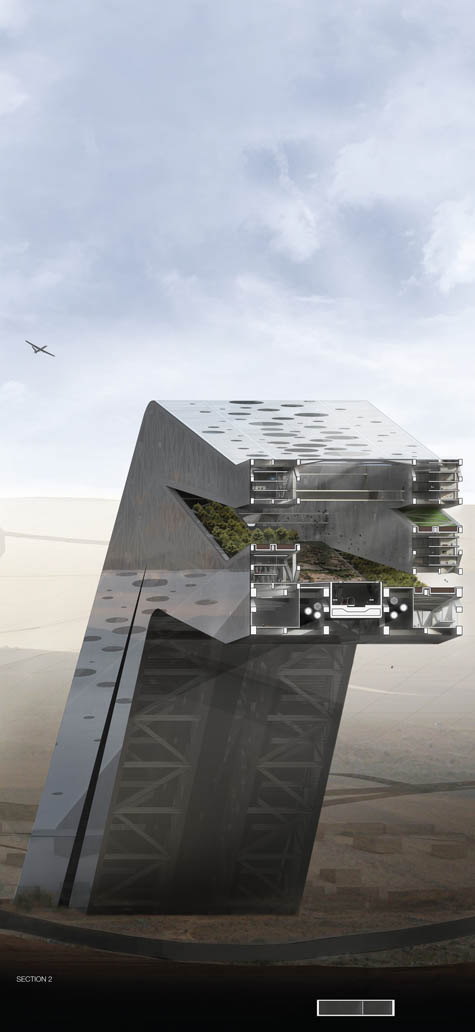

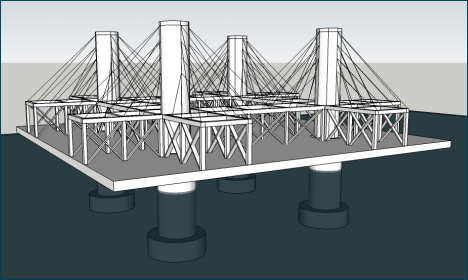

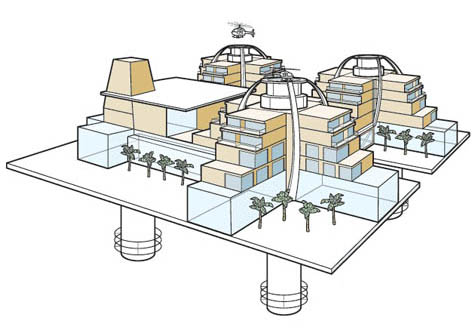

The result is a fantastic example of architectural speculation: genuinely massive – and impossibly cantilevered – bridges used as transport links, aerial housing, and skyborne agricultural complexes, all in one.

[Image: From The Continuous Enclave: Strategies in Bypass Urbanism by Viktor Ramos].

[Image: From The Continuous Enclave: Strategies in Bypass Urbanism by Viktor Ramos].

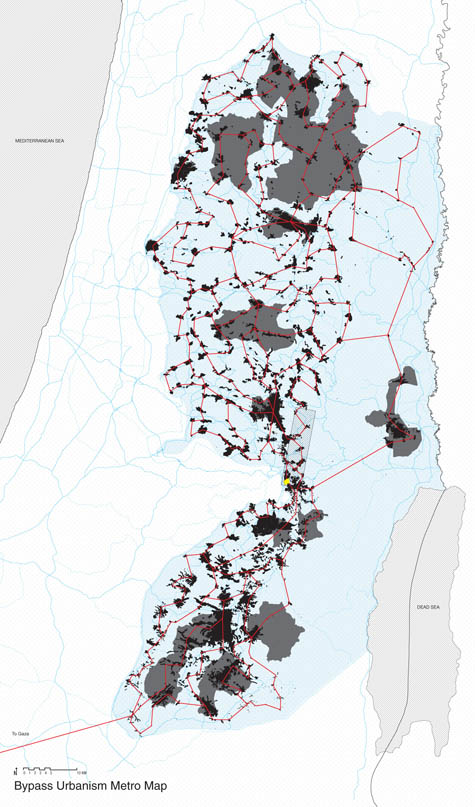

While clearly defying security protocols, as the “continuous enclave” and its network of bridges cross through sovereign Israeli airspace, these structures would link the dispersed islands of infrastructurally underserved territory now under Palestinian control.

From Ramos’s own project description:

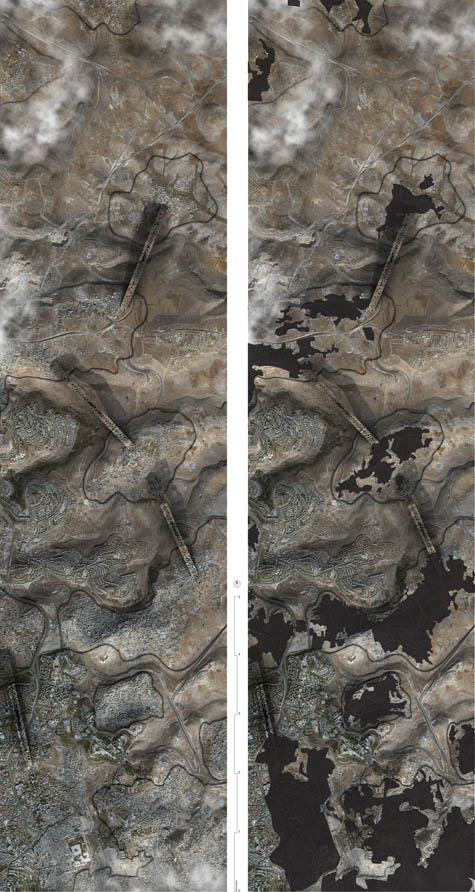

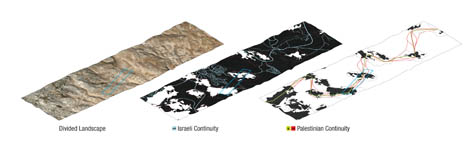

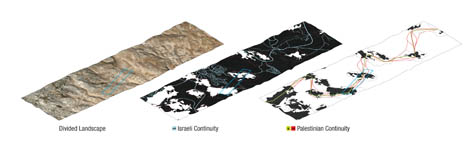

This thesis takes a formal approach to understanding the Israeli-Palestinian conflict by studying mechanisms of control within the West Bank. The occupation of the West Bank has had tremendous effects on the urban fabric of the region because it operates spatially. Through the conflict, new ways of imagining territory have been needed to multiply a single sovereign territory into many. It is only through the overlapping of two separate political geographies that they are able to inhabit the same landscape.

One might say that these bridges present us with the staple as geopolitical form.

[Image: From The Continuous Enclave: Strategies in Bypass Urbanism by Viktor Ramos; view poster-sized].

[Image: From The Continuous Enclave: Strategies in Bypass Urbanism by Viktor Ramos; view poster-sized].

“The Oslo Accords,” Ramos continues, “have been integral to this process of division.”

By defining various control regimes, the Accords have created a fragmented landscape of isolated Palestinian enclaves and Israeli settlements. The intertwined nature of these fragments makes it impossible to divide the two states easily. By connecting the fragments through a series of under- and overpasses, the border between the two states has shifted vertically.

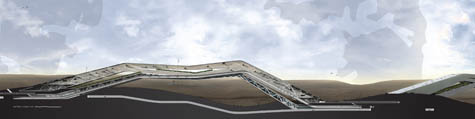

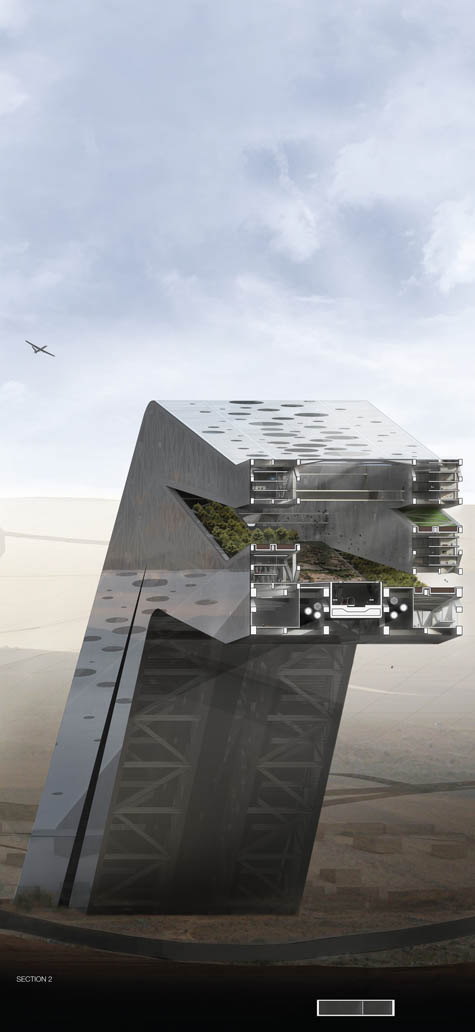

In the following cross-section, you can see the internal stacking of the space – an inhabited borderzone that weaves through the lower atmosphere.

[Image: From The Continuous Enclave: Strategies in Bypass Urbanism by Viktor Ramos; view larger].

[Image: From The Continuous Enclave: Strategies in Bypass Urbanism by Viktor Ramos; view larger].

To my mind, the project avoids the most obvious and expected pitfall of such an approach – which would be to suggest, naively, that architecture can, in and of itself, lead to a more thorough and lasting peace in the region, as if the entirety of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict would be eradicated if only they had better architecture.

Ramos instead uses the Oslo Accords as a kind of spatial source-code from which unanticipated structural forms might be extracted.

For those of you who have read Delirious New York, it’s as if the Oslo Accords have been turned into a geopolitically active 1916 Zoning Law. That law, of course, established spatial guidelines – for instance, enforcing setbacks for buildings, leading to an era in which skyscrapers rose up like ever-narrowing ziggurats – from which the buildings of Manhattan would then be shaped.

As Koolhaas himself writes, in the wake of the Zoning Law architects would “have to carve the final Manhattan archetype from the invisible rock of its zoning envelope in a campaign of specification.”

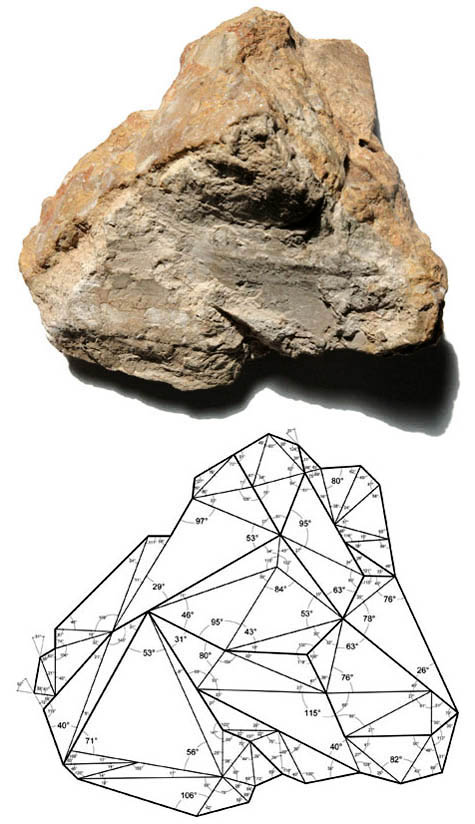

In Ramos’s project, that “invisible rock” consists of disputed territorial claims hovering virtually over the geography of the West Bank. The distinct new form of spatiality “carved” from that rock is the bypass.

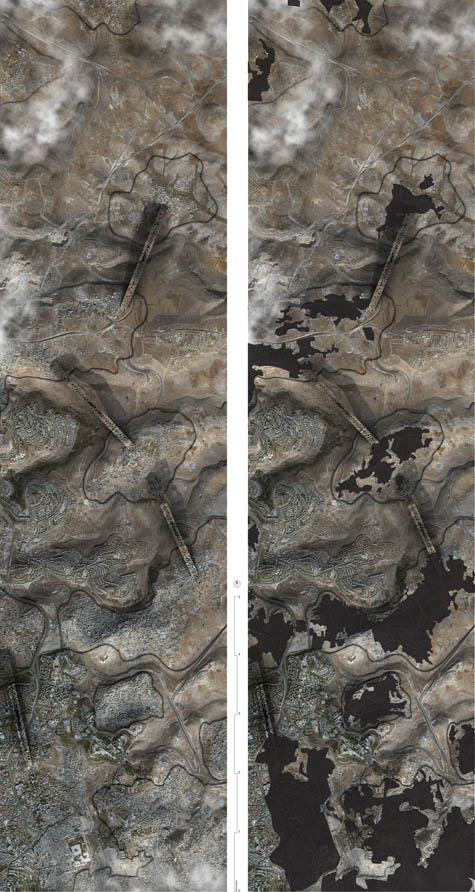

[Image: From The Continuous Enclave: Strategies in Bypass Urbanism by Viktor Ramos; definitely view larger].

[Image: From The Continuous Enclave: Strategies in Bypass Urbanism by Viktor Ramos; definitely view larger].

Again, from the project description:

One feature of the Oslo Accords is the bypass road which links Israeli settlements to Israel, bypassing Palestinian areas in the process. These are essential to the freedom of movement for the settlers within the Occupied Territories. Extrapolating on the bypass, this thesis explores the ramifications of a continuous infrastructural network linking the fragmented landscape of Palestinian enclaves. In the process, a continuous form of urbanization has been developed to allow for the growth and expansion of the Palestinian state. Ultimately, this thesis questions the potential absurdity of partition strategies within the West Bank and Gaza Strip by attempting to realize them.

Thus creating what Ramos calls bypass urbanism, or a self-connected maze of new territories in the sky.

[Image: From The Continuous Enclave: Strategies in Bypass Urbanism by Viktor Ramos; view much larger: top, bottom].

[Image: From The Continuous Enclave: Strategies in Bypass Urbanism by Viktor Ramos; view much larger: top, bottom].

There are any number of other directions such a project could go, but I’m particularly excited by the idea of applying this same sort of analysis to other conflict zones, elsewhere, all over the world.

Of course, the precedents for this are many. After all, what is the Berlin Wall but a piece of architecture pulled from the dreamscape of international legal infrastructure?

In fact, I’m reminded here of Rupert Thomson’s under-appreciated recent novel Divided Kingdom – especially because the basic premise of that book was at least partially inspired by Rem Koolhaas’s own student thesis project, Exodus, or The Voluntary Prisoners of Architecture. As Koolhaas wrote:

Once, a city was divided in two parts. One part became the Good Half, the other part the Bad Half. The inhabitants of the Bad Half began to flock to the good part of the divided city, rapidly swelling into an urban exodus. If this situation had been allowed to continue forever, the population of the Good Half would have doubled, while the Bad Half would have turned into a ghost town. After all attempts to interrupt this undesirable migration had failed, the authorities of the bad part made desperate and savage use of architecture: they built a wall around the good part of the city, making it completely inaccessible to their subjects.

The Wall was a masterpiece.

The U.S.–Mexico border would seem an obvious place for any investigation of “bypass urbanism” to begin; just today, the New York Times looked at the decaying after-effects of the Dayton Accords and their spatio-sovereign impact on the future of Bosnia; and Lebbeus Woods has long explored the architectural effects of political separation, from Paris and Berlin to Israel and Sarajevo, seeking out those fissures wherein geopolitics exhibits its own peculiar form of spatial tectonics.

But what new kinds of space might we yet extract from territorial agreements between, say, India and Pakistan over Kashmir, or Turkey and Greece over Nicosia – or, for that matter, what strange infrastructures might we build in Baarle-Hertog, what pavilions inspired by the Akwizgran Discrepancy, and how might most interestingly extract architecture from the international date line?

[Image: From The Continuous Enclave: Strategies in Bypass Urbanism by Viktor Ramos].

[Image: From The Continuous Enclave: Strategies in Bypass Urbanism by Viktor Ramos].

Even with so many precedents, it would seem, such studies have still barely begun.

You can see much, much larger versions of all of these images in this Flickr set: The Continuous Enclave: Strategies in Bypass Urbanism. They are incredibly detailed and well worth exploring in full!

(Viktor Ramos’s Continuous Enclave was produced at Rice University. It was advised by Troy Schaum under the direction of Fares el-Dahdah and Eva Franch, with additional input from John Casbarian and Albert Pope).

[Image: The basic platform; design your seastead atop this and win $1000].

[Image: The basic platform; design your seastead atop this and win $1000]. [Image: The sample design].

[Image: The sample design]. [Image: An illustrated variation of the sample design, from Wired magazine].

[Image: An illustrated variation of the sample design, from Wired magazine]. [Image: From

[Image: From

[Image: From

[Image: From  [Image: From

[Image: From  [Image: From

[Image: From  [Image: From

[Image: From

[Image: From

[Image: From  [Image: From

[Image: From  BLDGBLOG has unexpectedly popped up on a list of

BLDGBLOG has unexpectedly popped up on a list of  [Image: The finished “

[Image: The finished “

[Images: The “

[Images: The “ [Images: One the finished benches, via

[Images: One the finished benches, via

[Images: Testing out the landscape, via

[Images: Testing out the landscape, via  [Images: Via

[Images: Via  [Images: A handbook to spatial learning, via

[Images: A handbook to spatial learning, via  [Images: A Froebelian garden for kids – that is, a kindergarten – brings spatial education to Los Angeles in this archival image, courtesy of the

[Images: A Froebelian garden for kids – that is, a kindergarten – brings spatial education to Los Angeles in this archival image, courtesy of the  [Image: Two Structures, Death Valley, California, 2007, by

[Image: Two Structures, Death Valley, California, 2007, by  If you could design a bridge across the Bering Strait, connecting the U.S. to Russia, what would it look like? Come up with something good and you could win as much as $80,000 ($20,000, if you’re a student).

If you could design a bridge across the Bering Strait, connecting the U.S. to Russia, what would it look like? Come up with something good and you could win as much as $80,000 ($20,000, if you’re a student).  [Image: The “

[Image: The “ Benjamin Bratton of

Benjamin Bratton of  [Image: Courtesy of

[Image: Courtesy of  [Image: Courtesy of

[Image: Courtesy of

[Images: The rooms arrive by ship – before sliding open to form individual cabinettes. Courtesy of

[Images: The rooms arrive by ship – before sliding open to form individual cabinettes. Courtesy of  [Image: Courtesy of

[Image: Courtesy of  [Image: Courtesy of

[Image: Courtesy of  [Image: Courtesy of

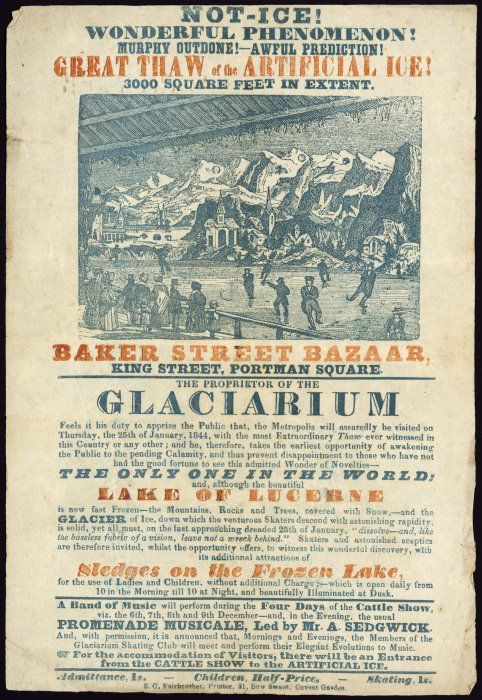

[Image: Courtesy of  [Image: “Not-ice! Wonderful phenomenon!” A flyer by the Proprietor of the London Glaciarium, 1844, from the

[Image: “Not-ice! Wonderful phenomenon!” A flyer by the Proprietor of the London Glaciarium, 1844, from the  [Image: The

[Image: The