I’m immensely pleased to announce BLDGBLOG’s first event, on January 13th in Los Angeles, to be hosted by the Center for Land Use Interpretation.

I’m immensely pleased to announce BLDGBLOG’s first event, on January 13th in Los Angeles, to be hosted by the Center for Land Use Interpretation.

The event is meant as a way to mark BLDGBLOG’s recent move to Los Angeles; to kick-start the new year in a conversationally exciting way; to celebrate being one of Yahoo’s top 25 web picks of 2006; and to meet a few of the one million readers who have now clicked through to read BLDGBLOG (some much-needed statistical caveats about that statement appear below) – and, thus, an event seemed like a good idea. It also just sounds fun.

So this Saturday, January 13th, from 3pm-5pm, at the Center for Land Use Interpretation in Culver City, Los Angeles, I’ll be introducing five speakers: Matthew Coolidge, Mary-Ann Ray, Robert Sumrell, Christine Wertheim, and Margaret Wertheim, who will speak for 15-20 minutes each.

Matthew Coolidge is Director of CLUI; as such, he’s one of the larger influences on BLDGBLOG, up there with J.G. Ballard, John McPhee, and Piranesi – so it’s immensely exciting for me to have him as a participant, and equally exciting that he and the CLUI staff are willing to host this event in their space. If you’re curious about CLUI’s work, consider purchasing their new book: Overlook: Exploring the Internal Fringes of America With the Center for Land Use Interpretation, or just stop by the Center at some point and say hello.

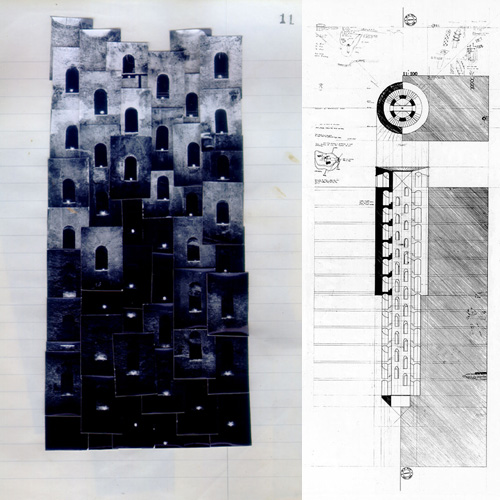

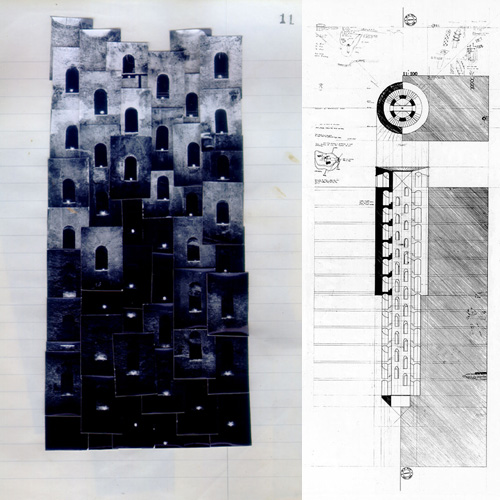

Back in 1997, then, I found myself in Rotterdam where I went to the Netherlands Architecture Institute several days in a row to use their architecture library; the NAi’s exhibit at the time was about Daniel Libeskind. While this proves that I’m possibly the world’s lamest backpacker, it also resulted in my stumbling across a copy of Mary-Ann Ray’s Seven Partly Underground Rooms and Buildings for Water, Ice, and Midgets, a book I highly recommend to just about anyone – and a book that may or may not even be responsible for my current interest in architecture.

Back in 1997, then, I found myself in Rotterdam where I went to the Netherlands Architecture Institute several days in a row to use their architecture library; the NAi’s exhibit at the time was about Daniel Libeskind. While this proves that I’m possibly the world’s lamest backpacker, it also resulted in my stumbling across a copy of Mary-Ann Ray’s Seven Partly Underground Rooms and Buildings for Water, Ice, and Midgets, a book I highly recommend to just about anyone – and a book that may or may not even be responsible for my current interest in architecture.

So when I saw last week that Mary-Ann still lives in LA, and that her firm had actually worked on the facade of the Museum of Jurassic Technology – located right next door to the Center for Land Use Interpretation – I immediately gave her a call; and now she’s a speaker at the event.

[Image: Mary-Ann Ray, from Seven Partly Underground Rooms and Buildings for Water, Ice, and Midgets].

[Image: Mary-Ann Ray, from Seven Partly Underground Rooms and Buildings for Water, Ice, and Midgets].

Robert Sumrell, meanwhile, is co-director of AUDC. AUDC’s work explores the fields of diffuse urbanism and network geography, whether that means analyzing Muzak as a form of spatial augmentation or photo-documenting the town of Quartzsite, Arizona.

Interestingly, Sumrell also works as a production designer for elaborate fashion shoots and other high-gloss, celebrity spectacles. If you’re a fan of Usher, for instance, don’t miss Sumrell’s Portfolio 2; if you like topless women surrounded by veils of smoke, see his Portfolio 1. I like Portfolio 1.

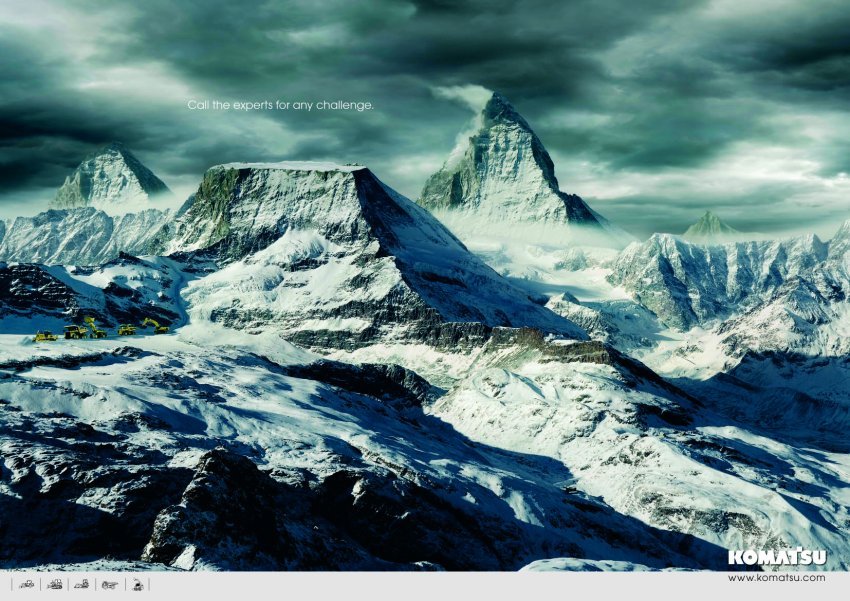

[Image: From Robert Sumrell’s Portfolio 4].

[Image: From Robert Sumrell’s Portfolio 4].

Then we come to Christine and Margaret Wertheim, co-directors of the Institute for Figuring, here in Los Angeles.

“The Institute’s interests,” they explain, “are twofold: the manifestation of figures in the world around us and the figurative technologies that humans have developed through the ages. From the physics of snowflakes and the hyperbolic geometry of sea slugs, to the mathematics of paper folding, the tiling patterns of Islamic mosaics and graphical models of the human mind, the Institute takes as its purview a complex ecology of figuring.”

Margaret will be presenting a hand-crocheted hyperbolic reef, “a woolly celebration of the intersection of higher geometry and feminine handicraft.” The reef is part craft object, part mathematical model in colored wool.

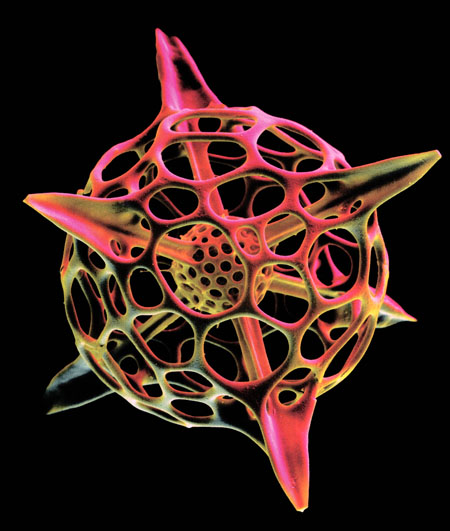

[Image: An example of “mega coral,” crocheted by Christine Wertheim].

[Image: An example of “mega coral,” crocheted by Christine Wertheim].

Margaret is also an ace interviewer; don’t miss her conversation with Nicholas Gessler, for instance, collector of analogue computers. While you’re at it, don’t miss her “history of space from Dante to the internet”.

Meanwhile, Christine’s interests lie more in the realm of logic and its spatial representations. Christine has curated an upcoming show at the Museum of Jurassic Technology around the work of Shea Zellweger, an “outsider logician” and former hotel switchboard operator who developed a three-dimensional, internally rigorous representational system for logical processes.

Christine will thus be speaking on what could be called an illustrated spatial history of logic.

[Image: Part of Shea Zellweger’s logical alphabet; image courtesy of Shea Zellweger, via the Institute for Figuring].

[Image: Part of Shea Zellweger’s logical alphabet; image courtesy of Shea Zellweger, via the Institute for Figuring].

Finally, the statistical caveats I mentioned above.

While it is true that my Sitemeter is now above one million – recording visitors to the site – it is also true that if you come to BLDGBLOG four times a week for a year, then you will be counted as 208 different people… So the accounting is a bit off.

Also, it is inarguably the case that at least 350,000 of those 1,000,000 visitors only visited one of the five following posts, which, thanks to Fark, Digg, MetaFilter, Boing Boing, etc., are overwhelmingly the most popular posts here: World’s largest diamond mine, Scientological Circles, “The city as an avatar of itself”, Transformer Houses, and Gazprom City.

Possible runners-up for that list – though those five really do take the cake – include, and I apologize for this blatantly self-indulgent yet strangely irresistible nostalgia trip: the interview with Simon Sellars, the interview with Simon Norfolk, the Aeneid-inspired look at offshore oil derricks, Chinese death vans, how to buy your own concrete utopia, Architectural Criticism, Where cathedrals go to die, the story of Joe Kittinger, London Topological, and L.A.’s high-tech world of traffic control. Actually, this one had a lot of readers, and the mud mosques were also quite popular…

But now I’ve wasted twenty minutes, assembling those links.

So I’ll link to others, instead. BLDGBLOG would still only be read by myself, my wife, and possibly two or three others if it hadn’t been for the early and/or ongoing enthusiasm of other websites who link in – including, but by no means limited to: Pruned, gravestmor, Archinect, things magazine, Inhabitat, Gridskipper, Boing Boing, Design Observer, Coudal, Artkrush, we make money not art, Subtopia, Ballardian, The Dirt, Apartment Therapy, Curbed LA and Curbed SF, City of Sound, Future Feeder, Archidose, Brand Avenue, Tropolism, hippoblog, Land+Living, Abstract Dynamics, Worldchanging, Warren Ellis, The Nonist, The Kircher Society, Conscientious, Centripetal Notion, and whoever it is that occasionally puts links to BLDGBLOG up on MetaFilter.

In any case, my final point is just to be honest and say that a million visitors is more like “a million visitors” – i.e. not quite a million visitors – and that, on top of that, many of those people only came through to see five or six particular posts in the first place. And that’s not even to mention the fact that many websites have more than a million visitors per month, and so the whole thing is not exactly awe-inspiring.

But who cares. If you’re in LA this weekend, consider dropping by; it’ll be a fun and casual event, not an academic conference, and you can tell me in person whether cone beats sphere.

(There’s also a full-size version of the event poster available).

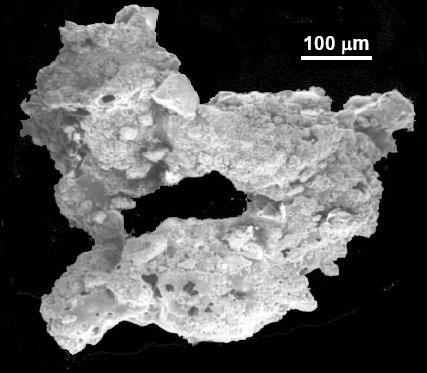

[Image: Via New Scientist].

[Image: Via New Scientist]. [Image: Jeff Shea/

[Image: Jeff Shea/ [Image: Map of Greenland, courtesy of the

[Image: Map of Greenland, courtesy of the  [Image: The mountains of eastern Greenland: a future archipelago. Via

[Image: The mountains of eastern Greenland: a future archipelago. Via  [Image: Greenland’s thawing landscape; photo by Jeff Shea/

[Image: Greenland’s thawing landscape; photo by Jeff Shea/ [Image: From Keith Kin Yan’s

[Image: From Keith Kin Yan’s  [Images: Two shots of Copenacre Quarry, via Nick McCamley’s

[Images: Two shots of Copenacre Quarry, via Nick McCamley’s  [Images: Two more shots of Copenacre Quarry, via Nick McCamley’s

[Images: Two more shots of Copenacre Quarry, via Nick McCamley’s  Just a quick note of thanks to everyone who came out

Just a quick note of thanks to everyone who came out  If you’re in LA and you’re reading this before 3pm, Saturday, January 13th, consider stopping by the

If you’re in LA and you’re reading this before 3pm, Saturday, January 13th, consider stopping by the

And there they are, driving away in yellow earth-moving equipment –

And there they are, driving away in yellow earth-moving equipment –  [Image:

[Image:  [Image: From

[Image: From  [Image: Circle Line Pinhole 16, from

[Image: Circle Line Pinhole 16, from  [Image:

[Image:  [Image:

[Image:  I’m immensely pleased to announce BLDGBLOG’s first event, on January 13th in Los Angeles, to be hosted by the

I’m immensely pleased to announce BLDGBLOG’s first event, on January 13th in Los Angeles, to be hosted by the  Back in 1997, then, I found myself in Rotterdam where I went to the

Back in 1997, then, I found myself in Rotterdam where I went to the  [Image: Mary-Ann Ray, from

[Image: Mary-Ann Ray, from  [Image: From Robert Sumrell’s

[Image: From Robert Sumrell’s  [Image: An example of “

[Image: An example of “ [Image: Part of Shea Zellweger’s logical alphabet; image courtesy of Shea Zellweger, via the

[Image: Part of Shea Zellweger’s logical alphabet; image courtesy of Shea Zellweger, via the  [Image: Mr. Housing Bubble; via

[Image: Mr. Housing Bubble; via  [Image: Photo by Manfred Cage, via

[Image: Photo by Manfred Cage, via  [Image:

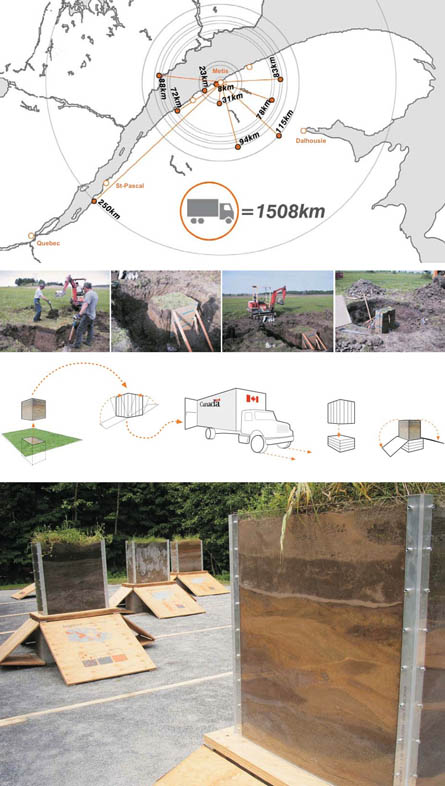

[Image:  [Image: From Soil Horizon, 2005, by Mason White and Lola Shepherd of

[Image: From Soil Horizon, 2005, by Mason White and Lola Shepherd of  [Image: Polar auroras on Saturn, via

[Image: Polar auroras on Saturn, via  [Image: A 19th-century

[Image: A 19th-century  [Image: The Prism 200, courtesy of

[Image: The Prism 200, courtesy of  [Image: An example of “neighborhood intensification,” or building smaller houses on smaller lots. Photo by John Morefield, courtesy of David Sarti, via

[Image: An example of “neighborhood intensification,” or building smaller houses on smaller lots. Photo by John Morefield, courtesy of David Sarti, via

[Images: Building by

[Images: Building by  [Image: Building by

[Image: Building by  In the arches of bridges, turbines.

In the arches of bridges, turbines.