[Images: Sze Tsung Leong, Seine I (2006), Baogang, Inner Mongolia (2003), and Jersey City (2002) from his Horizons Series, exhibited at the Yossi Milo Gallery earlier this year; discovered via Artkrush. The gallery’s accompanying press release gives some background on Sze Tsung Leong’s photos, but it concentrates entirely on his work from China. For more images, see The Built Environment].

[Images: Sze Tsung Leong, Seine I (2006), Baogang, Inner Mongolia (2003), and Jersey City (2002) from his Horizons Series, exhibited at the Yossi Milo Gallery earlier this year; discovered via Artkrush. The gallery’s accompanying press release gives some background on Sze Tsung Leong’s photos, but it concentrates entirely on his work from China. For more images, see The Built Environment].

Category: BLDGBLOG

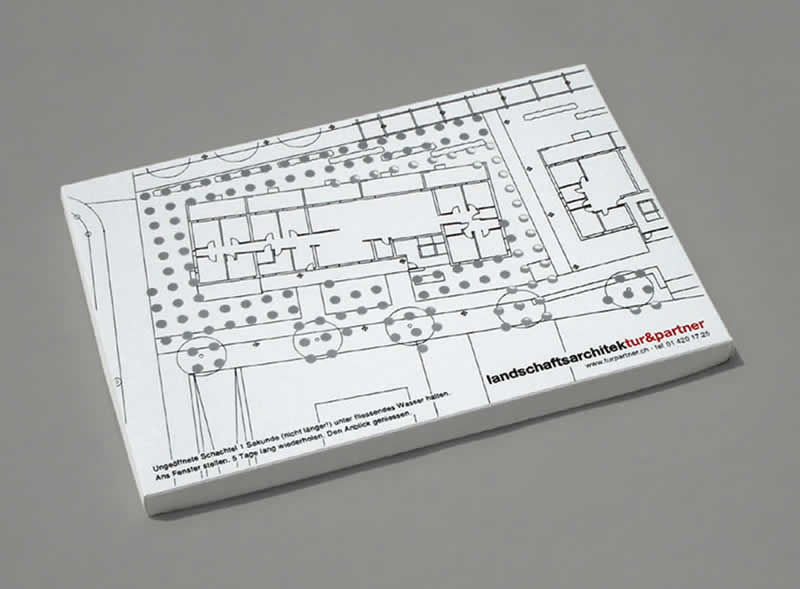

The business card and the garden smuggler

The Dirt introduces us to this business card slash micro-terrain by Tur & Partner, landscape architects. It’s a portable garden: impregnated with seeds, in the photosynthetic presence of sunlight and water, the paper eventually sprouts.

The Dirt introduces us to this business card slash micro-terrain by Tur & Partner, landscape architects. It’s a portable garden: impregnated with seeds, in the photosynthetic presence of sunlight and water, the paper eventually sprouts.

Which reminds me of a birthday card my brother once bought: if you buried the card and watered it, small seeds incorporated into the cardstock’s fibers would germinate. Which, in turn, makes me wonder if you could use this exact same method to smuggle rare plants out of totalitarian regimes intent on crushing botany within their borders… whether or not such regimes actually exist.

Or future trans-botanical geneticists, fleeing persecution, will hide their greatest seeds inside the pages of fake landscape guides, woven into the actual paper; they then bury their libraries in the soil of distant hillsides, and cloned roses and hybrid flowers soon grow.

(Card also featured at anArchitecture, among other places).

Earth Instrument

Artist Florian Dombois‘s Auditory Seismology project plays you the sound of earthquakes.

Artist Florian Dombois‘s Auditory Seismology project plays you the sound of earthquakes.

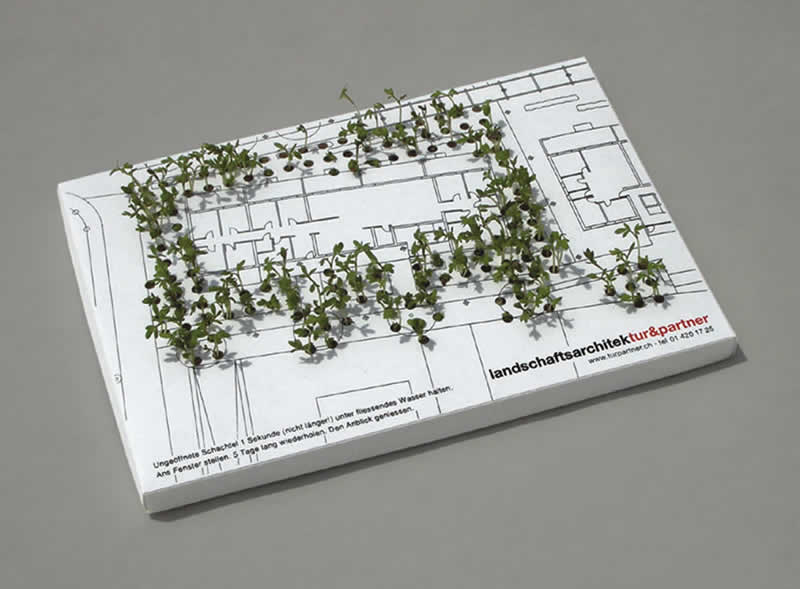

Using time-compression to accelerate the vibrational waves of global seismic activity, Dombois makes landscape events audible to human ears. Specifically, he writes, “if one compresses the time axis of a seismogram by about 2000 times and plays it on a speaker (so called ‘audification‘), the seismometric record becomes hearable and can be studied by the ear and [by] acoustic criteria.”

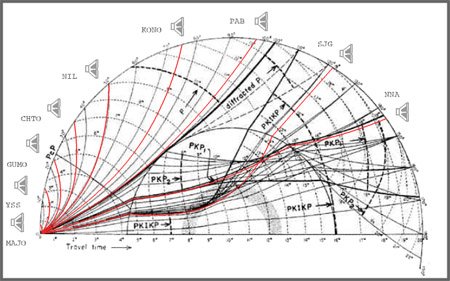

In this map of global tectonics, for instance, you can listen to the weird, rubbery snapping of plate boundaries.

In this map of global tectonics, for instance, you can listen to the weird, rubbery snapping of plate boundaries.

Dombois: “The sound of earthquakes at spreading zones differs much from earthquakes at subduction zones. Whereas earthquakes produced by plates that are drifting against each other appear as sharp and hard beats, an earthquake from a parting mid ocean ridge sounds more like a plop.”

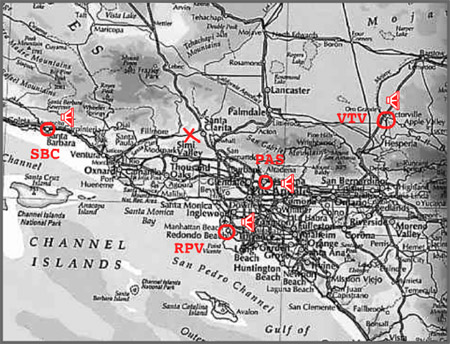

Meanwhile, Dombois also introduces us to the sonic seismicity of southern California, where the aftershocks of 1994’s Northridge quake sound like loose bits of metal banging against the side of a speeding bus. Then we go to Japan, whose plentiful subterranean dislocations come out like snaps of a drum. Finally, of course, we confront distance (the graph, featuring Earth’s surface, mantle, and core, that appears at the top of this post). Clicking on the seismic stations listed round that graph, you get short ambient works that weave together to form endless varieties of terrestrial drones.

Meanwhile, Dombois also introduces us to the sonic seismicity of southern California, where the aftershocks of 1994’s Northridge quake sound like loose bits of metal banging against the side of a speeding bus. Then we go to Japan, whose plentiful subterranean dislocations come out like snaps of a drum. Finally, of course, we confront distance (the graph, featuring Earth’s surface, mantle, and core, that appears at the top of this post). Clicking on the seismic stations listed round that graph, you get short ambient works that weave together to form endless varieties of terrestrial drones.

Click on more than one at the same time, and you can waste whole minutes of your life tuning faultlines and making dissonant chords of plates; the earth becomes your instrument.

Dombois’s exhibition of Auditory Seismology closes November 18th, at the galerie rachel haferkamp in Cologne.

(Thanks, Alex! Earlier: Fault Whispers, Dolby Earth, resonator.bldg, Sound dunes, and, to some extent, Podcasting the sun).

The Fountain

[Image: Resembling the birth, or perhaps death, of the universe under studio lights – or a black & white alternate ending to The Fountain – this is a sculpture by Michel Blazy from 5 Billion Years Later, at the Palais de Tokyo, Paris, photographed by booce. The image is best seen in its original size].

[Image: Resembling the birth, or perhaps death, of the universe under studio lights – or a black & white alternate ending to The Fountain – this is a sculpture by Michel Blazy from 5 Billion Years Later, at the Palais de Tokyo, Paris, photographed by booce. The image is best seen in its original size].

Payphone Warriors

Going on right now in a New York City near you is Payphone Warriors: “You and your teammates must dash across the blocks around Washington Square Park in a bid [to] control as many payphones as possible. You simply make a call from a payphone to the game system and enter your team number to capture a phone. For each minute your team controls that phone the team scores one point. Grab more phones for more points.”

Going on right now in a New York City near you is Payphone Warriors: “You and your teammates must dash across the blocks around Washington Square Park in a bid [to] control as many payphones as possible. You simply make a call from a payphone to the game system and enter your team number to capture a phone. For each minute your team controls that phone the team scores one point. Grab more phones for more points.”

And if someone complains that they actually need to use that phone… you know what to do.

And if someone complains that they actually need to use that phone… you know what to do.

(Brought to you by Abe Burmeister of Abstract Dynamics).

A lesson in abysses

[Image: The surface of the earth peeled away to reveal rock and fissures – a perfect excuse for one of my favorite quotations: “Look down well!” Jules Verne once wrote. “You must take a lesson in abysses.” Image produced by R.C. McDowell, G.J. Grabowski, and S.L. Moore for the U.S. Geological Survey; this is Kentucky. An alternative map, by A.C. Noger, is no less topo-optically extraordinary].

[Image: The surface of the earth peeled away to reveal rock and fissures – a perfect excuse for one of my favorite quotations: “Look down well!” Jules Verne once wrote. “You must take a lesson in abysses.” Image produced by R.C. McDowell, G.J. Grabowski, and S.L. Moore for the U.S. Geological Survey; this is Kentucky. An alternative map, by A.C. Noger, is no less topo-optically extraordinary].

(Earlier: BLDGBLOG’s Topographic Map Circus – although most of the links in that post are now broken).

Tativille

[Image: Tativille; a scene from Playtime. As Jacques Tati later explained, “there were no stars in the film, or rather, the set was the star, at least at the beginning of the film. So I opted for the buildings, facades that were modern but of high quality because it’s not my business to criticise modern architecture” – it was only his job to film it].

[Image: Tativille; a scene from Playtime. As Jacques Tati later explained, “there were no stars in the film, or rather, the set was the star, at least at the beginning of the film. So I opted for the buildings, facades that were modern but of high quality because it’s not my business to criticise modern architecture” – it was only his job to film it].

The idea that an abandoned film set could be archaeologically mistaken for a real city, ten, twenty, even a thousand years in the future, has popped up on BLDGLBOG before.

However, it turns out that there’s an equally interesting story to be found in Tativille, the instant city and film set built for Jacques Tati‘s now legendary Playtime. “Tativille came into existence,” we read in this PDF, “on the ‘Ile de France’ on a huge stretch of waste ground [in Paris]”:

Conceived by Jacques Tati and designed by Eugene Roman, it was strictly a cinema town, born of the needs of the film: big blocks of dwellings, buildings of steel and glass, offices, tarmacked roads, carpark, airport and escalators. About 100 workers laboured ceaselessly for 5 months to construct this revolutionary studio with transparent partitions, which extended over 15,000 square metres. Each building was centrally heated by oil. Two electricity generators guaranteed the maintenance of artificial light on a permanent basis.

During pre-production, “Tati visited many factories and airports throughout Europe before his cinematographer Jean Badal came to the conclusion that he needed to build his own skyscraper. Which is exactly what he did.”

In fact, he built Tativille: an entire city inhabited by no one but actors – who left after each day of filming.

One estimate puts the total mass of built space and material at “11,700 square feet of glass, 38,700 square feet of plastic, 31,500 square feet of timber, and 486,000 square feet of concrete. Tativille had its own power plant and approach road, and building number one had its own working escalator.”

Those hoping to visit the set’s cinematically Romantic remains are out of luck: “I would like to have seen it retained – for the sake of young filmmakers,” Tati claimed, “but it was razed to the ground. Not a brick remains.”

[Image: Tativille; from Playtime].

[Image: Tativille; from Playtime].

Notes for future screenwriters (who credit BLDGBLOG): in the summer of 2009 a delightful Ph.D. candidate from Columbia University, studying architectural history and writing her thesis on the lost sets of mid-20th century French cinema, will fly to Paris for three months. There, she rents a flat near the Seine, sketches buildings in blue ink on cafe napkins, reads Manfredo Tafuri, then sets up her most important interviews – but all is not well. She has strange dreams at night; she thinks she’s being followed; she has a mysterious run-in at the Musée D’Orsay; and she begins to suspect, upon deeper research, that Tativille wasn’t destroyed after all… Till, one day, in a beautifully shot scene at the French National Library – all weird angles and reflective glass walls – our heroine discovers that a small note has been slipped into her jacket pocket.

The note is actually a map, however, with directions addressed solely to her.

For, outside the city, in an arson-plagued banlieue, an old cluster of import warehouses silently waits.

She takes the train – and a small pocket-knife.

Then, standing alone inside one of those warehouses, torch in hand, she finds –

(Thanks, Nicky, for the tip! Of earlier interest: City of the Pharaoh).

Architecture is killing us all

A bunch of new Archinect t-shirts arrived this week. The three pictured above are my personal favorites – but check ’em out for yourself. Then buy ten thousand. Clothe an army with them. Wear one to bed. Run marathons in it. Wash cold.

A bunch of new Archinect t-shirts arrived this week. The three pictured above are my personal favorites – but check ’em out for yourself. Then buy ten thousand. Clothe an army with them. Wear one to bed. Run marathons in it. Wash cold.

(Note: Title is a reference to this post).

The Politics of Enthusiasm

[Image: Emiliano Granado, Night 1].

[Image: Emiliano Granado, Night 1].

Two months ago, Ballardian interviewed J.G. Ballard – something previously linked and summarized here – but now, insanely, BLDGBLOG has the wildly flattering privilege of being interviewed itself – joining Ballard, Bruce Sterling, and Iain Sinclair, among others.

Over the course of the interview, Simon Sellars and I talk about J.G. Ballard’s novels, from Concrete Island to Super-Cannes, The Drowned World to Crash – not to mention High-Rise – and we get there via a look at corporate office parks, Richard Meier, science fiction, Le Corbusier, the Paris riots, Archigram, Norman Foster, Sigmund Freud, sexual deviance, Daniel Craig, gated communities, the Taliban, Victor Gruen, future flooded Londons in the era of nonlinear climate change, Steven Spielberg, sports-car dealerships, Margaret Thatcher’s son, public surveillance, Rem Koolhaas…

[Image: Emiliano Granado, Environments 2].

[Image: Emiliano Granado, Environments 2].

Etc.

Read how speculative architectural treatises are actually “an extremely exciting, if totally unacknowledged, branch of the literary arts. Look at Thomas More’s Utopia. Or China Miéville. Or, for that matter, J.G. Ballard.” Discover how “the buildings and cities and landscapes in Ballard’s novels are more like psychological traps built by management consultants – not architects – who then fly overhead in private jets, looking down, checking whether their complicated theories of human cognition have survived the test. Where ‘the test’ is the world you and I now live in.” Learn how “perhaps manufacturing AK-47s is the only way to liven things up.” Argue whether or not “the problem with architecture is that it’s still there in the morning; you can’t turn it off.”

While you’re at it, gaze upon the fantastically Ballardian photography of Emiliano Granado, whose work both accompanies the interview and appears here.

[Image: Emiliano Granado, Environments 11].

[Image: Emiliano Granado, Environments 11].

Then join commenter #1, at the end of the interview, in disagreeing already with what I have to say… And have fun.

(Earlier, J.G. Ballard-inspired posts on BLDGBLOG: Concrete Island, Bunker Archaeology, 10 Mile Spiral, Silt, The Great Man-Made River, White men shining lights into the sky, Cities of Amorphous Carbonia – and so on).

Offshore (again)

Thanks to a perceptive reader, the Statoil ads that originally inspired BLDGBLOG’s Offshore post have been located.

Thanks to a perceptive reader, the Statoil ads that originally inspired BLDGBLOG’s Offshore post have been located.

So here they are…

You’re looking at offshore, utopo-stilted versions of Russia, Rome, New York, Baku, and the Sahara. Design enough of these and you could probably get an M.Arch. degree…

You’re looking at offshore, utopo-stilted versions of Russia, Rome, New York, Baku, and the Sahara. Design enough of these and you could probably get an M.Arch. degree…

All images by McCann.

(Via elisabethsblog – with huge thanks to Joakim Skajaa. And don’t miss Offshore).

Parking bands

The Economist reports today that the SW London borough of Richmond “is taking radical steps to curb greenhouse-gas emissions”:

The Economist reports today that the SW London borough of Richmond “is taking radical steps to curb greenhouse-gas emissions”:

In October its Liberal Democrat council announced a plan to price parking permits according to the amount of carbon dioxide emitted by residents’ vehicles. If the council passe[d] the proposal in a vote [that happened yesterday], the cost of an annual permit for cars in Band G – the worst polluters, such as SUVs, Renault Espaces and Jaguar X-Types – will triple to £300 ($568) from January 2007. Band A electric vehicles would be allowed to park for nothing; Band B cars, such as the hybrid Toyota Prius, would get a 50% reduction. Residents owning more than one vehicle would have to pay another 50% for each extra car. Thus a household with two Band G cars would see its annual parking bill rise from £200 to £750.

The article is quick to add that “Richmond residents emit more carbon dioxide per head than any other Londoners.”

(Earlier: Drive Britannia).