After participating in a roundtable discussion with architect Lorcan O’Herlihy yesterday at Dwell on Design, I decided to look into his work a bit more – and it’s been a great way to spend time. Lorcan has both a great sense of modernist architectural volume and a brilliant eye for color; the lime green he used on a multi-unit residence in West Hollywood, for instance, is extraordinary. I’ll see if I can dig up some photos of the finished building.

The following images, meanwhile, are just a random look at three or four of O’Herlihy’s most interesting projects. To start with, here is a recent building in Los Angeles, called Gardner 1050.

[Images: Gardner 1050, by Lorcan O’Herlihy].

[Images: Gardner 1050, by Lorcan O’Herlihy].

I’m a particular fan of the outdoor footbridges, as they criss-cross a shared entry courtyard in the all-pervading sunlight of LA.

O’Herlihy, you see, has a small thing for residential bridges: these next images feature the Fineman residence – a house with its own “enclosed glass-walled bridge.”

[Images: The Fineman house, by Lorcan O’Herlihy].

[Images: The Fineman house, by Lorcan O’Herlihy].

This next image gives us a bird’s-eye rendering of O’Herlihy’s proposal for a new dormitory and “Educational Facility” at CalArts – more information about which is available on O’Herlihy’s website.

[Image: Proposal for CalArts, by Lorcan O’Herlihy].

[Image: Proposal for CalArts, by Lorcan O’Herlihy].

In a nutshell, though, the circulation-friendly building complex uses a “shifted” east-west axis “to take full advantage of the complete spectrum of the optimal solar angle.” This not only “supports the passive ventilation system,” it means that “the need to artificially and mechanically condition an internal corridor year round can be eliminated resulting in a significant reduction in the net energy demand over the life of the building.”

Below, then, you see the architectural logic behind O’Herlihy’s Norton Avenue Lofts, going from a bare-bones diagram of abstract spatial volumes –

[Image: The Norton Avenue Lofts, by Lorcan O’Herlihy].

[Image: The Norton Avenue Lofts, by Lorcan O’Herlihy].

– to the final renderings of the project’s exterior.

[Images: The Norton Avenue Lofts, by Lorcan O’Herlihy].

[Images: The Norton Avenue Lofts, by Lorcan O’Herlihy].

In any case, I know I’m not exactly going into much detail with these projects – in fact, I’m just sort of whipping out a bunch of cool, unrelated images without offering any real or substantive analysis – but I still want to point out one more: O’Herlihy’s 12 Houses, an almost Bach-like study in formal variation.

[Image: 12 Houses by architect Lorcan O’Herlihy].

[Image: 12 Houses by architect Lorcan O’Herlihy].

The original idea behind 12 Houses, we read, was “to create individualized identities and experiences for each house using shared elements of design and construction.”

As a result, O’Herlihy generated “four prototypes”:

Starting from a simple main floor plan consisting of two adjoined rectangular bars, a second floor is created by pulling up or pushing down one bar – either in complement or contrast to the topography of each site. From these two formal gestures, four variations emerge: up, down, long, short. Further variation is produced by siting (for privacy and views), adjustment of each prototype in response to stringent building envelope limits, and a carefully-developed palette of exterior/interior materials.

I absolutely love the puzzle piece-like results.

[Image: 12 Houses by architect Lorcan O’Herlihy].

[Image: 12 Houses by architect Lorcan O’Herlihy].

But let me pre-empt some criticism right away: yes, this is simply another kind of suburban sprawl, destined to grace tasteless cul-de-sacs, surrounded by well-watered lawns and reachable only by private automobile – yet the houses are also beautifully devised and formally stimulating.

I also have an active soft spot for systems like this, and so I’m easily seduced by basic variations upon simple architectural plans – the same animating principal behind Palladianism, for instance. The mathematics of the ideal villa, indeed.

[Image: 12 Houses by architect Lorcan O’Herlihy].

[Image: 12 Houses by architect Lorcan O’Herlihy].

O’Herlihy’s 12 Houses are apparently slated for construction, too: they should be ready for inhabitation by Spring 2008.

For more projects by Lorcan O’Herlihy, book a visit to his firm’s website.

North Carolina-based architect

North Carolina-based architect  [Images: The

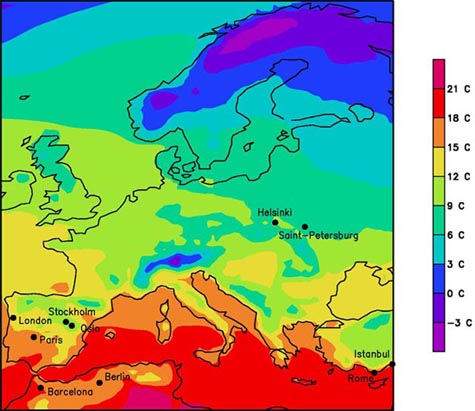

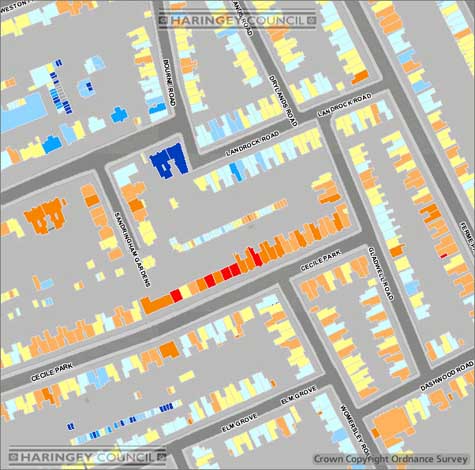

[Images: The  The map is initially quite confusing, but it shows that London will have the climate of Lisbon, Portugal; Berlin will have the climate of northern Algeria (!); and Oslo will feel like Barcelona (and so on).

The map is initially quite confusing, but it shows that London will have the climate of Lisbon, Portugal; Berlin will have the climate of northern Algeria (!); and Oslo will feel like Barcelona (and so on).  They had noticed, apparently, that some recent fires involving stately old Victorians occurred immediately after those houses’ residents had got divorced.

They had noticed, apparently, that some recent fires involving stately old Victorians occurred immediately after those houses’ residents had got divorced.  What really happened, the psychiatrist proposed, was that the houses themselves had been blamed, or scapegoated, for the interpersonal strife that once occurred within them – and those houses had thus been destroyed.

What really happened, the psychiatrist proposed, was that the houses themselves had been blamed, or scapegoated, for the interpersonal strife that once occurred within them – and those houses had thus been destroyed.  [Image: The

[Image: The

[Images: Michelle Kaufmann’s

[Images: Michelle Kaufmann’s  [Image: Another freakishly beautiful photograph by

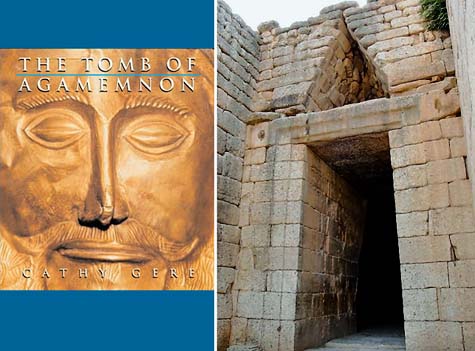

[Image: Another freakishly beautiful photograph by  In preparation for tomorrow’s interview, then, I’ll start with a quick look at the book that first hooked me:

In preparation for tomorrow’s interview, then, I’ll start with a quick look at the book that first hooked me:  The book is compulsively readable, and it’s also short: I started reading it one afternoon and had finished it by that evening.

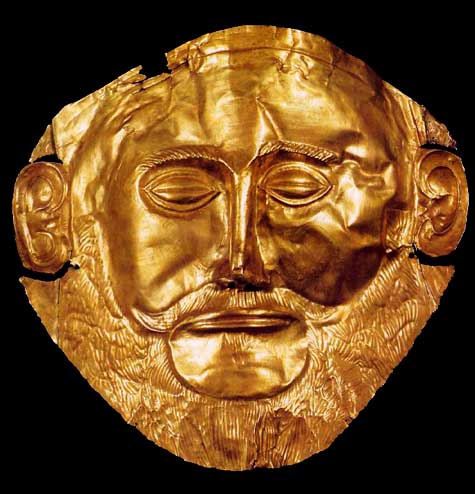

The book is compulsively readable, and it’s also short: I started reading it one afternoon and had finished it by that evening.  [Image: The “mask of Agamemnon”].

[Image: The “mask of Agamemnon”]. And it will probably horrify Gere to hear me say this – because this implies that I completely misread the whole book – but

And it will probably horrify Gere to hear me say this – because this implies that I completely misread the whole book – but  [Image: This Gloucestershire silk mill is

[Image: This Gloucestershire silk mill is  More specifically:

More specifically: The practice itself is referred to as “

The practice itself is referred to as “ [Image: Rome’s

[Image: Rome’s  [Image: A “short drop” in Toronto’s

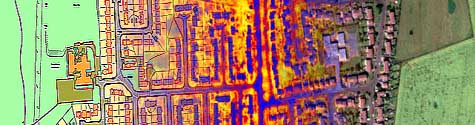

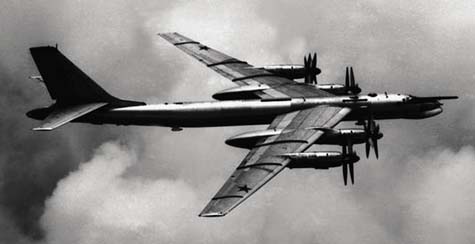

[Image: A “short drop” in Toronto’s  [Image: A Russian TU-95; the TU-95s were originally “designed as bombers but are now frequently used for maritime reconnaissance.” They have recently been intercepted in the north Atlantic].

[Image: A Russian TU-95; the TU-95s were originally “designed as bombers but are now frequently used for maritime reconnaissance.” They have recently been intercepted in the north Atlantic].  [Image: A model of the

[Image: A model of the  [Image: A model of the

[Image: A model of the

[Images: Models of

[Images: Models of