[Image: Illustration by Holl Liou, courtesy of Wired].

[Image: Illustration by Holl Liou, courtesy of Wired].

Wired reports on “a small team of Silicon Valley millionaires” who hope to develop “a new option for global citizenship: A permanent, quasi-sovereign nation floating in international waters.”

They call this practice seasteading.

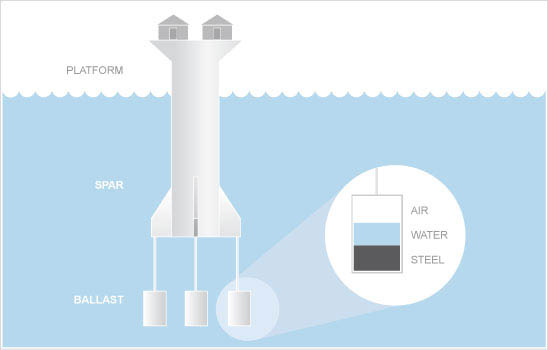

The seasteaders want to build their first prototype for a few million dollars, by scaling down and modifying an existing off-shore oil rig design known as a “spar platform.” In essence, the seastead would consist of a reinforced concrete tube with external ballasts at the bottom that could be filled with air or water to raise or lower the living platform on top. The spar design helps offshore platforms better withstand the onslaught of powerful ocean waves by minimizing the amount of structure that is exposed to their energy.

Build enough of these spar platforms and you’ve got yourself a “deep-water city-state.”

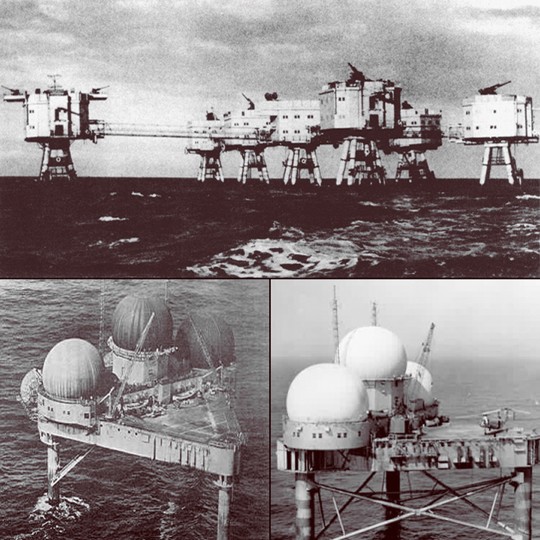

The group’s 300-page book on the managerial practicalities of running “modular seastead groups” references everything from Sealand, the offshore micronation, to the Texas Tower, to houseboats, to the dangers of tropical storms.

[Images: The Maunsell Towers (top), unmentioned by the libertarian seasteaders, and the Texas Tower (bottom)].

[Images: The Maunsell Towers (top), unmentioned by the libertarian seasteaders, and the Texas Tower (bottom)].

They touch on the political and economic circumstances involved in steading the high seas, including SOLAS, the International Convention for the Safety of Life at Sea, and UNLOS, the United Nations Law of the Sea. They mention the process of buying a Flag of Convenience, in which hopeful microsovereigns can “shop around for a country that has the least objectionable laws and rates, and count on the seller’s apathy to minimize restrictions. A seastead is potentially high-profile, and if it proves a serious embarrassment to a registrar it may lose its flag.”

The seastead’s power storage needs are then discussed in terms of electrochemical batteries, gravity batteries, and supercapacitors, and the production of this power will, the authors presume, come from wind and solar systems, and even one or two fuel-powered generators. Of course, there’s also the power of the sea to consider – and the authors’ “favorite” method for harvesting “wave power” is something called Isaac’s Wave Pump.

[Image: Tapping into oceanic motion with BioPower Systems].

[Image: Tapping into oceanic motion with BioPower Systems].

In any case, one can fantasize forever about endless small changes in the construction of a functioning seastead. (Note to Chronicle Books: publish an architectural guide to seasteading; it’ll be a huge hit on Father’s Day).

What interests me here, aside from the architectural challenge of erecting a durable, ocean-going metropolis, is the fact that this act of construction – this act of building something – has constitutional implications. That is, architecture here proactively expands the political bounds of recognized sovereignty; architecture becomes declarative.

The stakes for design have gone up, in other words. It’s not just a question of producing better loft apartments, for which you can charge an extra $300,000, or of perfecting the art of luxury kitchen space; it’s a question of designing architecture for extreme conditions and, should your architecture survive, thus opening up room for a new form of what might be called post-terrestrial sovereignty, i.e. governance freed from landed terrain.

Which is not to be confused with advocacy of the project; I just like discussing its political side-effects: architecture becomes wed with, indeed inseparable from, a political project. It is construction in the service of constitutionality (and vice versa).

Wed with oceanic mobility, the architecture of seasteading doesn’t just aesthetically augment a natural landscape; it actually encases, or gives physical shape to, a political community. It is architecture as political space in the most literal sense.

[Images:

[Images:  [Images: Three examples of maps displayed on

[Images: Three examples of maps displayed on

[Image: From the series

[Image: From the series

[Image: “

[Image: “ [Image: A map of the

[Image: A map of the  [Image: Vertical House by

[Image: Vertical House by  [Image: Vertical House by

[Image: Vertical House by  [Image: From an article by

[Image: From an article by  [Image: Another spread from

[Image: Another spread from  [Image: The

[Image: The  [Image: The

[Image: The

[Images: Two spreads from

[Images: Two spreads from  [Image: Spatial City by Yona Friedman: “The framework was to be erected first, and the residences conceived and built by the inhabitants inserted into the voids of the structure.” Courtesy of the

[Image: Spatial City by Yona Friedman: “The framework was to be erected first, and the residences conceived and built by the inhabitants inserted into the voids of the structure.” Courtesy of the  [Image: From

[Image: From  [Image: Felix Hess assembles similar sound machines, next to a photo of an unrelated concert hall].

[Image: Felix Hess assembles similar sound machines, next to a photo of an unrelated concert hall].

[Image: Ice in Cranberry Lake, Ontario, photographed by Michael Runtz; via

[Image: Ice in Cranberry Lake, Ontario, photographed by Michael Runtz; via

[Image: From

[Image: From

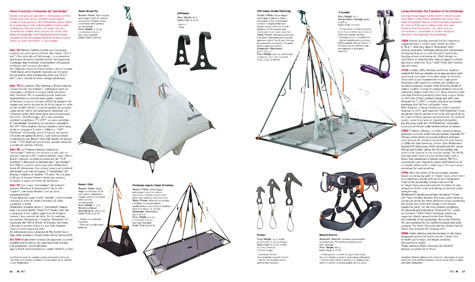

[Images: From

[Images: From

[Images: From

[Images: From

[Image: From

[Image: From  I’ve been going through old magazines to find articles that I hope to read, re-read, or even incorporate into the final edits of the BLDGBLOG Book – and so tonight I came across the January 2007 issue of

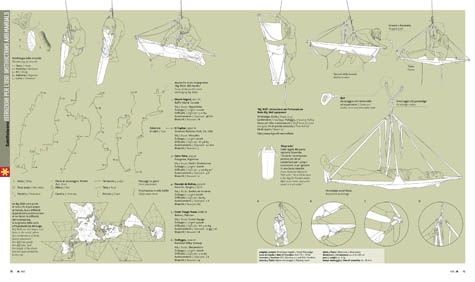

I’ve been going through old magazines to find articles that I hope to read, re-read, or even incorporate into the final edits of the BLDGBLOG Book – and so tonight I came across the January 2007 issue of