The Third & The Seventh, a short film by Alex Roman uploaded to Vimeo just last month and already viewed more than half a million times, is an entirely computer-generated, exquisitely rendered, photorealistic tour of architectural space.

While Frank Gehry’s Disney Concert Hall unfortunately makes an appearance, the remainder of the film tours some pavilions, museums, wind farms, and other urban icons, from both inside and out, that you will no doubt recognize.

There’s no plot as such, but the imagery is of such ridiculously high quality—although I could skip the soundtrack—that this seems much more visually promising to me then, say, the much hyped, half-a-billion dollar technologies used in Avatar; I would rather watch the opening two or three minutes of Roman’s film stretched out to feature length and threaded through with some narrative cues than revisit James Cameron’s badly rendered blue giants.

[Images: A Calatravian still from Alex Roman’s The Third and the Seventh].

[Images: A Calatravian still from Alex Roman’s The Third and the Seventh].

This also seems to be yet more evidence that architecture students are literally just on the cusp of expertise in several different industries, and that even the briefest of collaborations with interested writers could push many student projects instantly over into fully realized narrative films. While I’m aware that many architecture students couldn’t care less about this—they didn’t, after all, apply to film school—I think it is nonetheless a strategically interesting option to consider when it comes to developing, presenting, and recontextualizing spatial ideas: a slight tweak here and there, a presentation of the most bare-bones scenario imaginable, and you’ve gone from student thesis project to La Jetée after one late night and some 5 Hour Energy drinks…

[Images: Stills from Alex Roman’s The Third and the Seventh].

[Images: Stills from Alex Roman’s The Third and the Seventh].

In any case, Roman’s website includes galleries of some gorgeous film stills, including these details, these lighting effects, a few examples of “man-made vs. nature,” and multiple glimpses of classic furniture.

[Image: From Alex Roman’s The Third and the Seventh].

[Image: From Alex Roman’s The Third and the Seventh].

However, Vimeo seems to be loading quite slowly at the moment, so I’ve included a few stills here.

[Image: Alex Roman, The Third and the Seventh].

[Image: Alex Roman, The Third and the Seventh].

Here’s hoping Roman gets the attention he deserves for this, and that we someday see his work popping up in more venues. The film was created using 3ds Max, V-Ray, After Effects and Premiere.

(Thanks to Jim Rossignol and Ilari Lehtinen for the tip!)

[Image: Lebbeus Woods, from

[Image: Lebbeus Woods, from  [Image: Ahmadinejad emerges from a highway tunnel; photo by Henghameh Fahimi for the Agence France-Presse, via the

[Image: Ahmadinejad emerges from a highway tunnel; photo by Henghameh Fahimi for the Agence France-Presse, via the  [Images: A civilization beneath the trees; images via

[Images: A civilization beneath the trees; images via  [Image: Piles of road salt outside Toronto. Photo by Flickr-user

[Image: Piles of road salt outside Toronto. Photo by Flickr-user  [Image: The Pelican Nebula, photographed by Charles Shahar at the

[Image: The Pelican Nebula, photographed by Charles Shahar at the  [Image: John Constable, Seascape Study with Rain Cloud (1827); originally spotted at

[Image: John Constable, Seascape Study with Rain Cloud (1827); originally spotted at

[Images: (top) The bewilderingly beautiful Cat’s Paw Nebula, photographed by T.A. Rector at the University of Alaska, Anchorage; (middle) The Witch Head Nebula, photographed by Davide De Martin at the Palomar Observatory; (bottom) The Rosette Nebula, photographed by J.C. Cuillandre (Canada France Hawaii Telescope) and Giovanni Anselmi (Coelum Astronomia)].

[Images: (top) The bewilderingly beautiful Cat’s Paw Nebula, photographed by T.A. Rector at the University of Alaska, Anchorage; (middle) The Witch Head Nebula, photographed by Davide De Martin at the Palomar Observatory; (bottom) The Rosette Nebula, photographed by J.C. Cuillandre (Canada France Hawaii Telescope) and Giovanni Anselmi (Coelum Astronomia)]. [Image: “

[Image: “ [Image:

[Image:  [Image: Greg Lynn’s

[Image: Greg Lynn’s  [Image: From

[Image: From

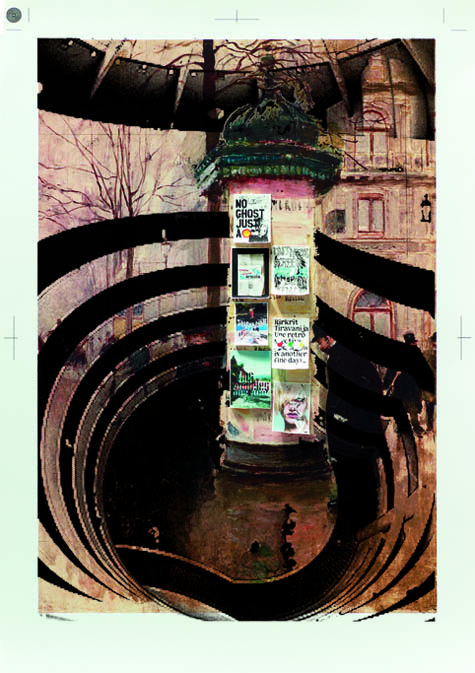

[Images: From

[Images: From  [Image: From

[Image: From  [Images: From

[Images: From  [Image: From

[Image: From  [Image: Flow Show by

[Image: Flow Show by  [Image: Untitled by

[Image: Untitled by

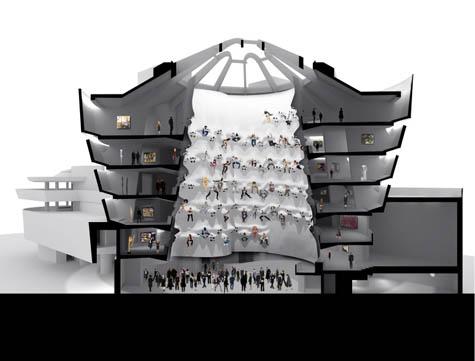

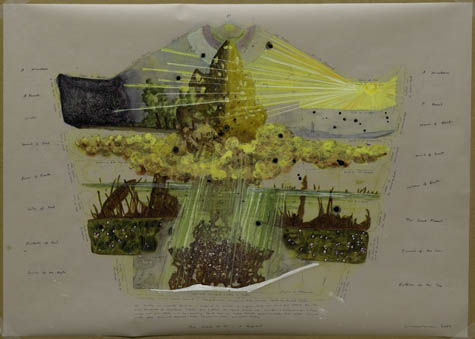

[Images: (top) Let’s Jump! by

[Images: (top) Let’s Jump! by

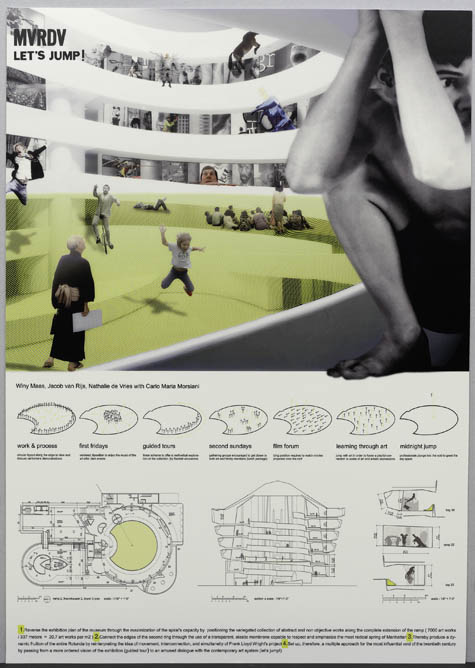

[Images: (top) Morris in Guggenheim by

[Images: (top) Morris in Guggenheim by  [Image: State Fair Guggenheim by

[Image: State Fair Guggenheim by  [Image: Untitled by

[Image: Untitled by  [Image: A poster for

[Image: A poster for  [Image: Photo by Flickr-user

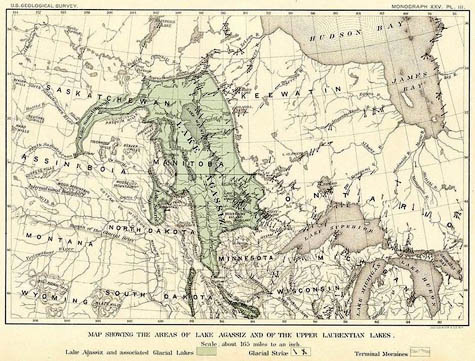

[Image: Photo by Flickr-user  [Image: A map of glacial

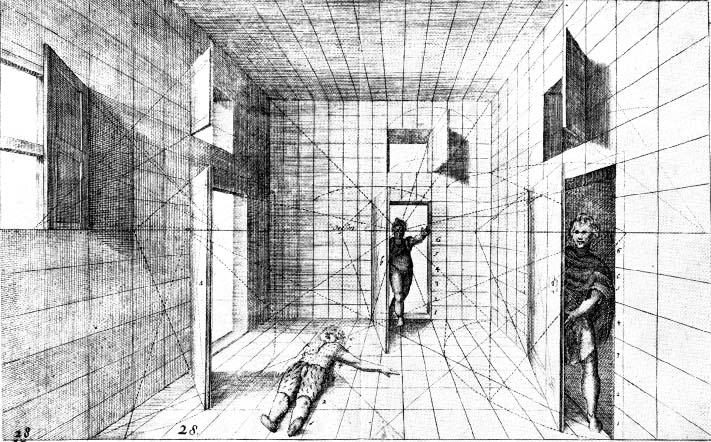

[Image: A map of glacial  [Image: Perspective by

[Image: Perspective by  [Images: Two diagrams stitched together showing acoustics of bat echolocation at

[Images: Two diagrams stitched together showing acoustics of bat echolocation at  [Images: All images courtesy of

[Images: All images courtesy of