[Image: A pyramid at Giza, the earth archaeo-surgically opened at its base; courtesy of the Brooklyn Museum; for what it’s worth, this photo just knocks me out].

[Image: A pyramid at Giza, the earth archaeo-surgically opened at its base; courtesy of the Brooklyn Museum; for what it’s worth, this photo just knocks me out].

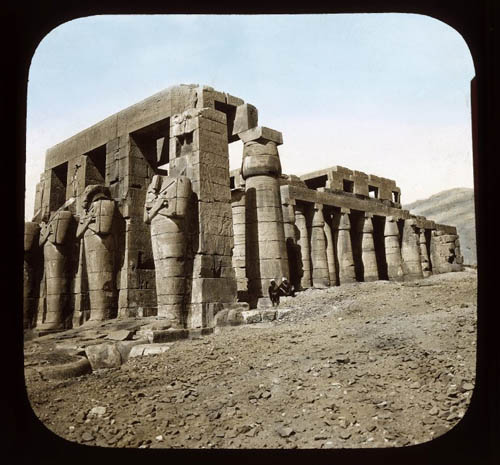

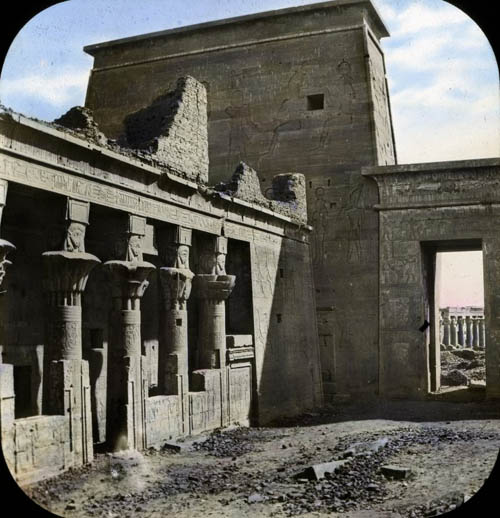

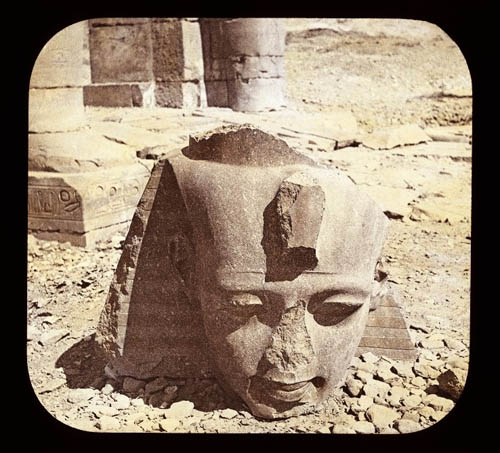

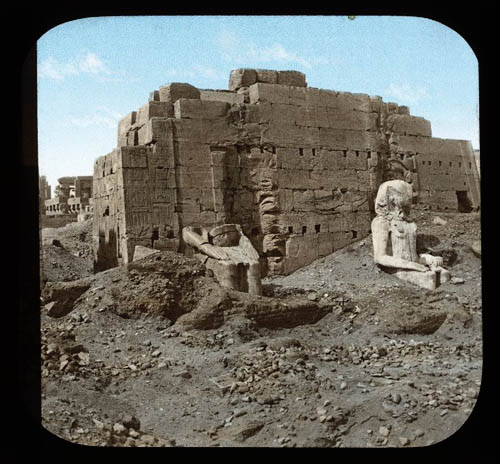

The Brooklyn Museum has an amazing collection of old lantern slides from Egypt, documenting that country’s archaeological history and monumental remains.

The shots above and immediately below, in which we see the pyramids at Giza, exude a stage-set quality: the diffuse and hand-colored light, the foreshortened perspective, and the cut-away glimpse into a world of subterranean vaults lending an air of surreality to the whole collection.

[Image: Giza, courtesy of the Brooklyn Museum; for what it’s worth, this photo just knocks me out].

[Image: Giza, courtesy of the Brooklyn Museum; for what it’s worth, this photo just knocks me out].

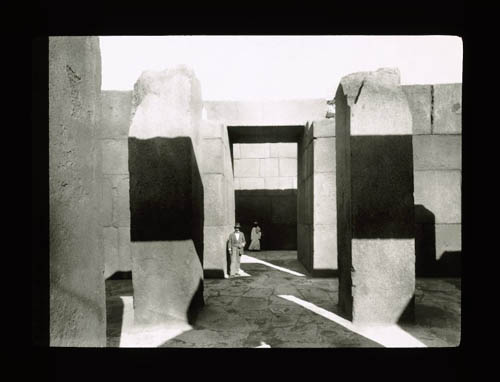

Overall, the architecture captured in these images is a mixture of deeply shaded, geometric minimalism—

[Images: Brutalism at Giza, circa 2,500 B.C.; courtesy of the Brooklyn Museum].

[Images: Brutalism at Giza, circa 2,500 B.C.; courtesy of the Brooklyn Museum].

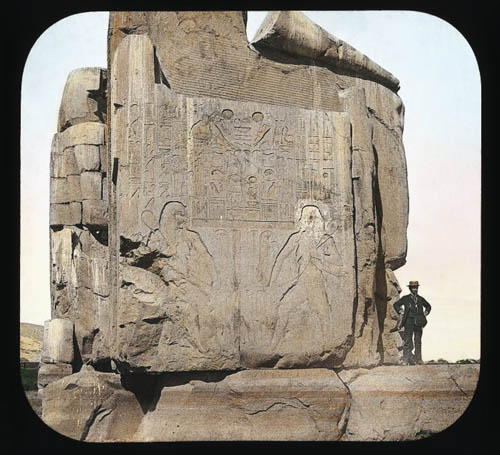

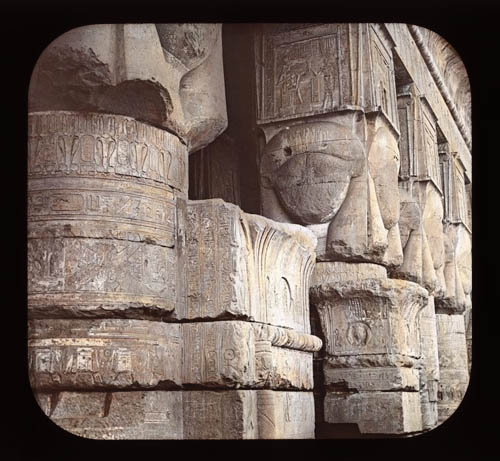

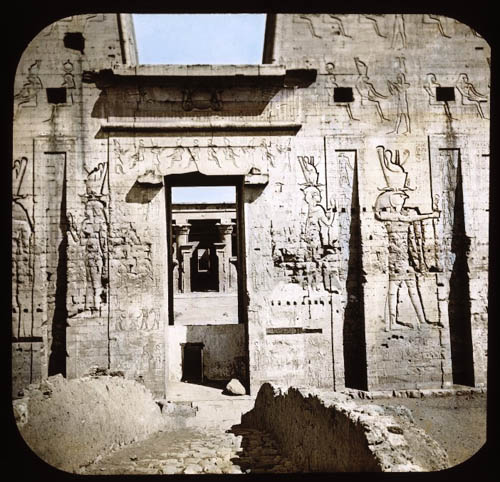

—wed with moments of ornamental grandeur, as hieroglyphic bas-reliefs, revealed by passing angles of sunlight, offer whole worlds of spatial detail. Stone inscriptions become less like something you might read, in other words, and more of a spatial experience in their own right.

[Image: Ruins in light, courtesy of the Brooklyn Museum].

[Image: Ruins in light, courtesy of the Brooklyn Museum].

I’m reminded here of one of my favorite stories of all time, which is that of physicist Luis Alvarez. In the September/October 2008 issue of Archaeology magazine, author Samir Patel explained how Alvarez used a device called a muon detector “to scan the inside of an ancient structure,” which, in this case, was Khafre’s pyramid at Giza.

“Working with Egyptian scientists in the late 1960s,” Patel explains, Alvarez “gained access to the Belzoni chamber, a humid vault deep under the pyramid.” There, “Alvarez’s team set up a muon detector called a spark chamber, which included 30 tons of iron sheeting, in the underground room.” This image—of foreign physicists building iron rooms beneath the pyramids in a search for secret chambers based on cosmic particles raining down from above—is one of the coolest things I have ever read in my life.

[Image: An illustrated depiction of the physicists’ sub-pyramidal adventures; view larger].

[Image: An illustrated depiction of the physicists’ sub-pyramidal adventures; view larger].

As it happens, Alvarez’s work was not without local controversy:

Suspicion of the research team ran high—here was a group of Americans with high-tech electronics beneath one of Egypt’s most cherished monuments. “We had flashing lights behind panels—it looked like a sci-fi thing from Star Trek,” says Lauren Yazolino, the engineer who designed the detector’s electronics.

Alvarez’s humid iron room beneath the pyramid—like a collaborative project by Lebbeus Woods and Mike Mignola—took one full year to perform its work. At that point, when the team finally took a long look through its gathered data, Yazolino “spotted an anomaly, a region of the pyramid that stopped fewer muons than expected, suggesting a void.”

There were still undiscovered rooms inside the structure.

[Image: Tombs at Abu Simbel, Egypt, courtesy of the Brooklyn Museum].

[Image: Tombs at Abu Simbel, Egypt, courtesy of the Brooklyn Museum].

In any case, you can find these and many more on the Brooklyn Museum’s website; just go to the Lantern Slide Collection (including this write-up of the Lantern Slide Collection’s history) or to this Flickr set. The specific images seen here come from subsidiary collections: Giza, Thebes, Karnak, Philae, Abu Simbel, Edfu, Denderah, and so on.

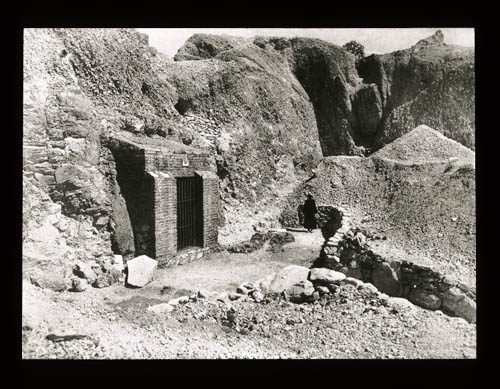

This final image, below, featuring a doorway embedded in the hills—perhaps leading down into iron rooms, and further into spark chambers, and beyond even those into unmapped humid vaults—is particularly fantastic.

[Image: The hollow hills of Egypt’s Middle Kingdom, courtesy of the Brooklyn Museum].

[Image: The hollow hills of Egypt’s Middle Kingdom, courtesy of the Brooklyn Museum].

(Via @stevesilberman).

[Image: Tree pollen map, brought to you by the

[Image: Tree pollen map, brought to you by the  [Image: Proposal for a new

[Image: Proposal for a new  [Image: Super Colossal’s competition-winning design for

[Image: Super Colossal’s competition-winning design for  [Image: “

[Image: “ [Image: Via

[Image: Via  [Image: A speculative future subway map by

[Image: A speculative future subway map by

[Images: Maps by

[Images: Maps by  [Image: By

[Image: By  [Image: The

[Image: The

[Images: From the

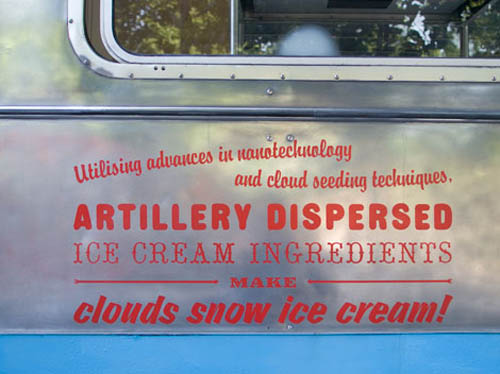

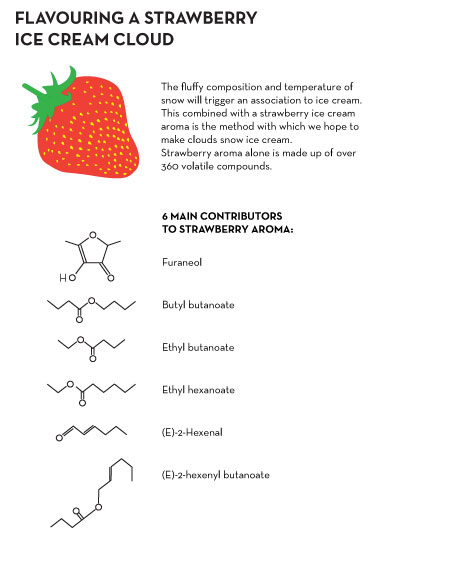

[Images: From the  [Image: A how-to guide for precipitating strawberry ice cream by Zoe Papadopoulou and Cathrine Kramer].

[Image: A how-to guide for precipitating strawberry ice cream by Zoe Papadopoulou and Cathrine Kramer]. [Image: O.T. (2006) by

[Image: O.T. (2006) by  [Image: Abstract thought is a warm puppy (2008) by

[Image: Abstract thought is a warm puppy (2008) by  [Image: From

[Image: From

[Images:

[Images:  [Image: From

[Image: From  [Image: From

[Image: From  [Image:

[Image:

[Images: From

[Images: From

[Images:

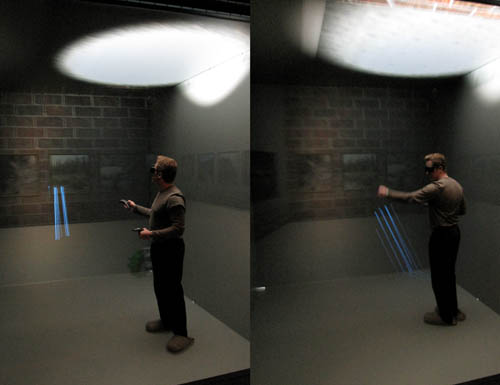

[Images:  [Image: The CAVE at the Desert Research Institute in Reno, now called the

[Image: The CAVE at the Desert Research Institute in Reno, now called the

[Image: Daniel Coming, Principle Investigator of the

[Image: Daniel Coming, Principle Investigator of the  [Image: Touring virtual light].

[Image: Touring virtual light].

[Image: Cthulhoid satellites appear in space before you, rotating three-dimensionally in silence].

[Image: Cthulhoid satellites appear in space before you, rotating three-dimensionally in silence].

[Images: Photos by BLDGBLOG and

[Images: Photos by BLDGBLOG and  [Image: The

[Image: The  [Image: Work by

[Image: Work by  [Image: Work by

[Image: Work by

[Images:

[Images:  [Image: By

[Image: By

[Images: All works by

[Images: All works by  [Image: By

[Image: By

[Images: All works by

[Images: All works by  [Image: Work by

[Image: Work by

[Images: By

[Images: By  [Image: Map via University of Maine

[Image: Map via University of Maine