[Image: An example of gravitational lens effects, via Wikipedia.]

[Image: An example of gravitational lens effects, via Wikipedia.]

Over at WIRED, Daniel Oberhaus, author of the recent book Extraterrestrial Languages, takes a look at some proposals from NASA’s Innovative Advanced Concept (NIAC) program. “Among this year’s NIAC grants,” Oberhaus writes, “are proposals to turn a lunar crater into a giant radio dish, to develop an antimatter deceleration system, and to map the inside of an asteroid. But the most eye-popping concept of the bunch was advanced by Slava Turyshev, a physicist at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory who wants to photograph an exoplanet by using the sun as a giant camera lens.”

There is much more specific information in Oberhaus’s piece—about gravitational lensing, etc. etc.—but the following detail is killer. “Unlike a camera lens,” we read, “the sun doesn’t have a single focal point, but a focal line that starts around 50 billion miles away and extends infinitely into space. The image of an exoplanet can be imagined as a tube less than a mile in diameter centered on this focal line and located 60 billion miles away in the vast emptiness of interstellar space. The telescope must align itself perfectly within this tube so that you could draw an imaginary line from the center of the telescope through the center of the sun to a region on the exoplanet.”

Cameras in space, waiting to be discovered—or where astronomy and cinematography become the same pursuit.

Seen this way, the solar system is more like a maze of optical effects, a topology of entangled image-tubes and horizon lines, of gravitational mirages streamed from one side of the galaxy to the next, torqued, lensed, and ribboned into geometric shapes we then struggle to unknot with the right billion-dollar instrumentation.

Along those lines, recall this excellent post on Xenogothic following last year’s unprecedented “photo” taken of a black hole. According to Xenogothic, this curious anti-photo depicting the absence of light reveals “the true, formless nature of photography and our photographies-to-come… The further out into the imperceptible universe we reach, the quicker we must get used to seeing images which are ostensibly not-for-us.” Imaging black holes is art history by other means.

[Image: Black hole, via Xenogothic.]

[Image: Black hole, via Xenogothic.]

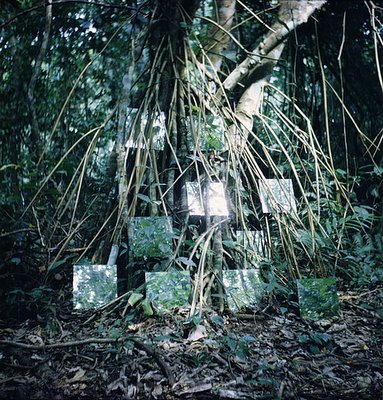

In fact, all of this reminds me of one of my favorite museums in the world, the National Museum of Cinema in Turin, Italy, which begins its history of cinema with a display of circular mirrors, anamorphic paintings, perspectival diagrams, and other optical tricks that, in the proper historical context, seem indistinguishable from magic. The birth of “cinema,” we might say, occurred when someone distorted light with mirrors; its origins are rooted in illusion and reflection, not projection and electricity.

In any case, imagine magicians of the near-future, performing for audiences aboard relativistic spacecraft, making stars disappear by manipulating image-tubes in the voids between planets. Gravitational lensing will pass from a niche science into popular spectacle.

And then, of course—the inevitable next step in a Christopher Priest novel—these magical effects of stellar camouflage, Xenogothic’s “photographies-to-come,” will become weaponized, militarized, transformed into tools for catastrophically redirecting light through space and extinguishing distant worlds.

From an optical effect in the prehistory of cinema to relativistic gravitational lensing in the abstracts of NASA to future galactic conquerors casually folding closed their image-tubes and making entire planets disappear.

[Image: Ningbo, China, via

[Image: Ningbo, China, via  [Image: Guangzhou, China, via

[Image: Guangzhou, China, via  [Image: Beijing, China, via

[Image: Beijing, China, via