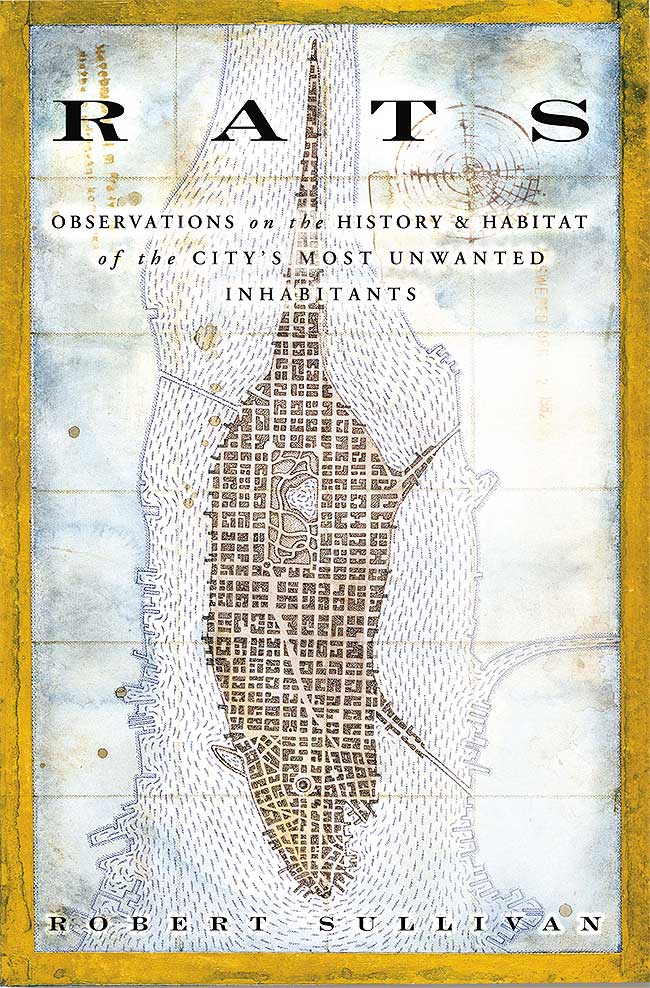

In his book Rats, Robert Sullivan—an author whose work we previously reviewed here—offers a glimpse of how the city is seen through the eyes of the pest-control industry.

[Image: Rats by Robert Sullivan].

[Image: Rats by Robert Sullivan].

Effective rodent control requires a very specific kind of spatial knowledge, Sullivan suggests, one that often eludes architects and city planners.

Sullivan quotes one rat-control professional, for instance, who “foresees a day when he will be hired to analyze a building’s weaknesses, vis-à-vis pests and rodents… ‘They design buildings to support pigeons and for infiltration by rodents because they don’t think about it. Grand Central Station, right? They just renovated it, right? Who knows what they spend on that, right? You know how much they spend on pest control? You know how much they budgeted? Nothing. I did all the extra work there, but they had to pay us out of the emergency budget.'”

Pest control here becomes an explicitly architectural problem, something you can design both for and against. Imagine an entire degree program in infestation-resistant urban design.

Sullivan points out that a massive, urban-scale architectural intervention, in the form of a quarantine wall fortifying all of New York City against rats, was once tentatively planned: “There was a time in New York, in the 1920s,” he writes, “when scientists proposed a great wall along the waterfront to shut out rats completely, to seal out rats and, thus, forever end rat fear. Eventually, though, the idea was deemed implausible and abandoned: rats will always get through.”

But it’s the particular subset of urban knowledge that has been actively cultivated within the pest control industry that fascinates me here. Sullivan spends a bit of time with a man named Larry Adams, a municipal rodent control expert. “If you hang around Larry long enough,” Sullivan says, “you realize that he sees the city in a way that most people don’t—in layers.” And what follows is well worth quoting in full:

He sees the parks and the streets and then he sees the subways and the sewers and even the old tunnels underneath the sewers. He sees the city that is on the maps and the city that was on the maps—the city’s past, the city of hidden speakeasies and ancient tunnels, the inklings of old streams and hills.

“People don’t realize the subterranean conditions out there,” he likes to say. “People don’t realize the levels. People don’t realize that we got things down there from the Revolution. A lot of people don’t realize that there’s just layers of settlers here, that things just get bricked off, covered up and all. They’re not accessible to people, but they are to rats. And they have rats down there that have maybe never seen the surface. If they did, then they’d run people out. Like in the movies. You see, we only see the tail end of it. And we only see the weak rats, the ones that get forced out to look for food.”

The book’s wealth of rat-catching anecdotes are often unbelievable. “More than anything,” Sullivan reflects, “I have learned from exterminators that history is crucial in effective rat analysis.”

In fact, history is everything when it comes to looking at rats—though it is not the history that you generally read; it is the unwritten history. Rats wind up in the disused vaults, in long underground tunnels that aren’t necessarily going anywhere; they wind up in places that are neglected and overlooked, places with a story that has been forgotten for one reason or another. And to find a rat, a lot of times you have to look at what a place was. One exterminator I know tells the story of a job on the Lower East Side in an old building where rats kept appearing, nesting, multiplying, no matter how many were killed. The exterminator searched and searched. At last, he found an old tunnel covered by floorboards, a passageway that headed toward the East River. The tunnel was full of rats. Later, he discovered that the building had housed a speakeasy during Prohibition.

Or this disconcerting image of an infested basement that was never fully demolished—it was simply forgotten, walled off beneath the surface of the city. Here, Sullivan visits an abandoned lot with a rat-catching expert named Isaac, writing that, “just before we drove off, two men walked by and stopped at the fence; they looked into the abandoned lot and spoke with Isaac in Spanish.”

They told Isaac that they remembered when the lot was the site of an old wooden house that had become abandoned and filled with rats. They remembered the house being demolished and partially buried—the basement was still there, they said. They pointed to the ground, saying that the old home was still beneath it, still rat-infested.

What a perfectly haunting line: They pointed to the ground, saying that the old home was still beneath it, still rat-infested. (And if anyone out there has read The Rats by James Herbert, you might remember that the novel begins with a vaguely similar urban image).

[Image: A “rat king,” via Wikimedia].

[Image: A “rat king,” via Wikimedia].

Speaking later with Mike, another rat-control expert, Sullivan learns how the stratigraphy of the city takes shape in the mind of the exterminator: “I was getting ready to leave—Mike was just too busy. But then Mike was reminded of an aspect of the nature of rats in the city, and as he put down the phone, he said, ‘You know, I heard there are three layers of sewer lines.’ He counted them off on his fingers. ‘There are the ones from the 1800s, the ones from the 1700s, and the ones they don’t have maps for anymore. Once in a while, they use that old line, when they’re doing construction or something, and you read in the papers that there are hundreds of rats coming up. Well, those rats that are in the third line, they haven’t even seen man before.’”

These stratigraphies of infestation are wonderfully horrifying—but also perfectly and immediately available to the architect and urban planner as practical design challenges. How does one deal with “what was on the maps,” as Sullivan phrases it, while at the same time designing a pest-unfriendly metropolis?

Taking as their design target rats and other “unwanted inhabitants” of the city, as Sullivan phrases it, what inspired collaborations could we develop amongst public health inspectors, urban ecologists, pesticide manufacturers, historical cartographers, city archivists, materials scientists (Sullivan writes, for instance, that Larry Adams, mentioned earlier, has actually developed his own special mix of rat-resistant concrete: “With his expertise, Larry has developed his own rat-eradication techniques, such as concrete mixed with broken glass to keep the rats from gnawing through the concrete. ‘Sometimes, they’ll still cut through before the concrete hardens. So sometimes, I use glass and industrial-strength steel wool and put it in with the concrete and make one big goop with it’”), and, of course, architects and planners? How realistic—let alone ethical—a design challenge is the rodent-free metropolis?

[Image: From

[Image: From  [Images:

[Images:  [Image: From

[Image: From  [Image: Bow-hunting amidst the reeds, from

[Image: Bow-hunting amidst the reeds, from  [Image: An awesomely sinister photo from

[Image: An awesomely sinister photo from