New Orleans is not the only city to be faced with a future of indefinite flooding – nor is it the only city in the world below sealevel.

The entire nation of the Netherlands, for instance, provides perhaps the most famous example of urbanized land reclaimed from the Atlantic seafloor. “Polders” is the Dutch name for such rigorously flood-controlled territory, and an exhibition literally even now being held at the Rotterdam-based Netherlands Architecture Institute explores the polders’ geotechnical creation.

The polders’ “rationally organized landscape is unique, but also vulnerable,” the NAI explains. Vulnerable to overdevelopment – as well as to catastrophic flooding.

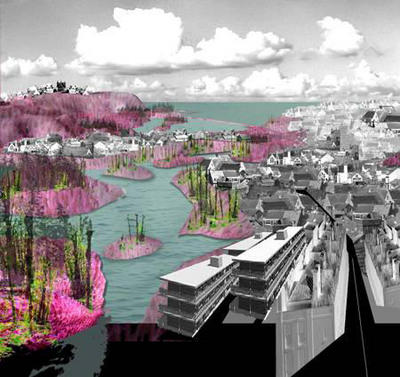

The 2005 Rotterdam International Architecture Biennale, in fact, takes nothing less than “The Flood” as its central, organizing theme – with one particular sub-focus being Water City*.

[Image: The metropolis, the flood, the boundaries of architectural design.]

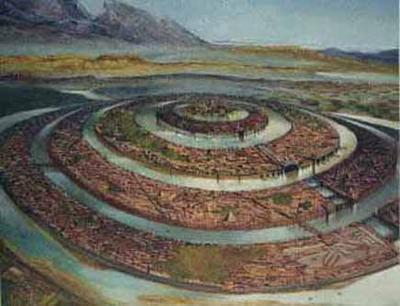

In April and May, 2005, The New Yorker ran a three-part article by Elizabeth Kolbert, called “The Climate of Man,” on the subject of human-induced climate change. The third part, published on 9 May 2005, ends with a description of how “one of the Netherlands’ largest construction firms, Dura Vermeer, [has] received permission to turn a former R.V. park into a development of ‘amphibious homes'” – a floating city. (The Guardian also has an article about this.)

“The amphibious homes all look alike,” Kolbert says. Floating on the River Meuse in Maasbommel, “they resemble a row of toasters. Each one is moored to a metal pole and sits on a set of hollow concrete pontoons. Assuming that all goes according to plan, when the Meuse floods the homes will bob up and then, when the water recedes, they will gently be deposited back on land. Dura Vermeer is also working to construct buoyant roads and floating greenhouses” – the entire human race gone hydroponic.

As Dura Vermeer’s environmental director says: “There is a flood market emerging.”

[Image: A floating house, moored to the earth, in Maasbommel.]

Further afield, the year 2005 has seen major flooding in Europe, India, and Bangladesh, to name but a few sites of major hydrological catastrophe.

In Mumbai, India, *The Economist* explains, the 2005 floods “uncovered long-term failures. Not enough had been done to maintain Mumbai’s ageing infrastructure, such as storm-drains and sewers. Worse, new building had weakened the city’s defences. Large areas of protective mangrove had been razed – in one notorious example, to make way for a golf course. Developers have built on wetlands, clogging natural drainage channels. River banks have been reclaimed and become slums.”

And then there is Bangladesh. “From the air,” we read, also in The Economist (most of their articles are for subscribers only, it’s really irritating), “Bangladesh looks less like a country than one vast lake, dotted with thousands of tiny islets, clumps of trees and houses. Few boats ruffle the placid floodwaters: there is nowhere to go.” And yet “[t]he great lake of Bangladesh is in reality a network of nearly 250 rivers.”

New Orleans, Rotterdam, Bangladesh, Mumbai: 2005 will be the year of flooded infrastructure and overwhelmed cities.

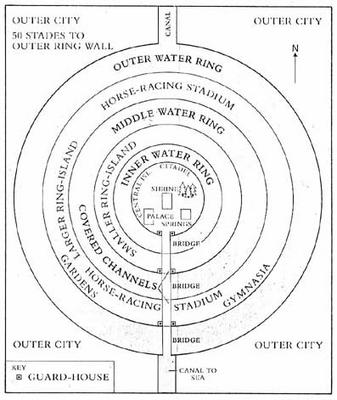

And so if Atlantis sets the gold standard for civilizations lost to floods – forget Noah – then it’s interesting that Atlantis, even before Katrina occurred, was back in the news this year (though I suppose it is every year). As already explored elsewhere on BLDGBLOG, Atlantis’s island home may (or may not) be in the Straits of Gibraltar.

The real issue, however, that the infrastructural possibility of Atlantis brings to the fore – or, rather, that Katrina brings to the fore, through the hydrological destruction of New Orleans – is revealed quite clearly in the following artist’s representations of what Atlantis might have looked like:

Atlantis, city of dikes and levees, city of canals and inland seas, city of water-smart urban design and hydrological planning – it, too, was swallowed by the oceans, and destroyed.

This thread continues in Katrina 1: Levee City (on military hydrology); and Katrina 3: Two anti-hurricane projects (on landscape climatology) – both on BLDGBLOG.