[Image: “Laser Cut Record” by Amanda Ghassaei].

[Image: “Laser Cut Record” by Amanda Ghassaei].

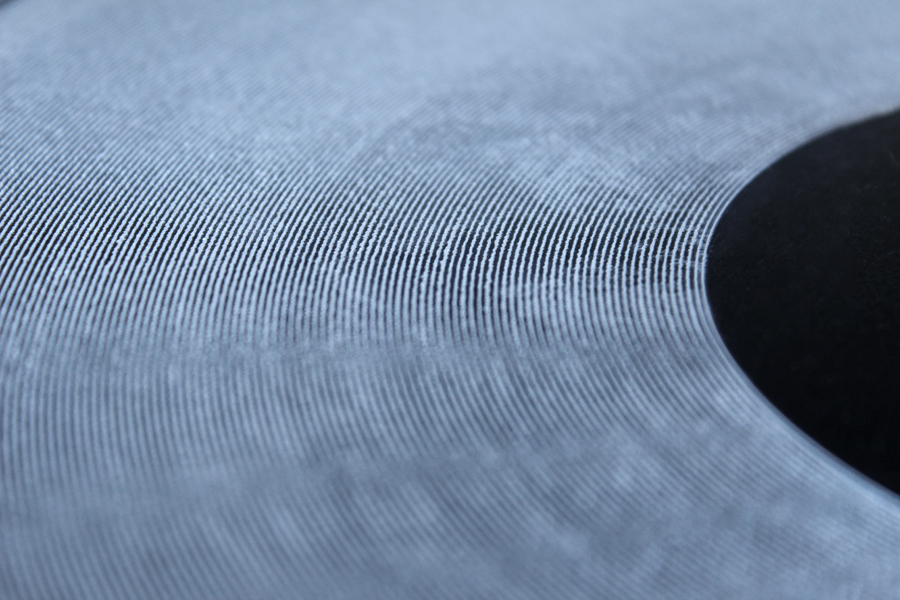

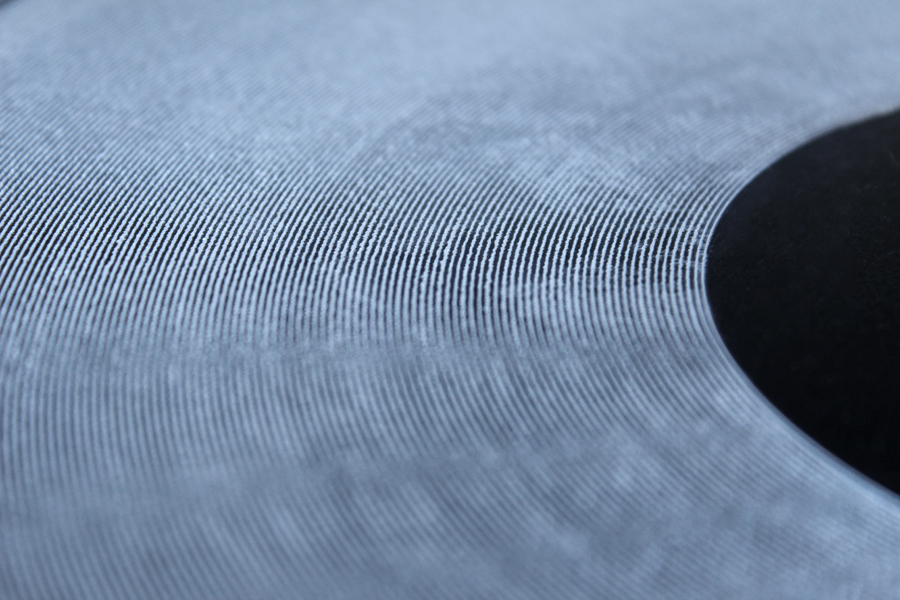

An incredible example of what can be done with laser-cutting, Amanda Ghassaei’s project “Laser Cut Record” features music inscribed directly into cut discs of maple wood, acrylic, and paper, resulting in lo-fi but playable records.

For what they are, the otherwise scratchy and off-kilter audio quality is actually quite amazing, and the sounds themselves are made all the more haunting and strange by the crackling noise and resonance of the material that hosts them.

[Image: “Laser Cut Record” by Amanda Ghassaei].

[Image: “Laser Cut Record” by Amanda Ghassaei].

Some technical details are available at Ghassaei’s Instructables page, and you can see the laser-cutting itself at work in the following video.

I’m reminded of a short letter called “Acoustic Recordings from Antiquity,” written to the Proceedings of the IEEE in August 1969 by a man named Richard G. Woodbridge III. The somewhat eccentric Mr. Woodbridge explains that he has been researching accidental recording of sounds found, after careful analysis, on the surfaces of physical objects rescued from antiquity—in particular, pieces of pottery originally shaped on potters’ wheels (seen here as a kind of primordial record platter).

Woodbridge even claims some sounds have been “recorded” as re-playable waves in the slowly drying shapes of oil paintings.

To listen to these lost recordings, the letter suggests, you simply hold a record cartridge near the work of pottery in question, such that the needle of the phonograph can “be positioned against a revolving pot mounted on a phono turntable (adjustable speed) ‘stroked’ along a paint stroke, etc.” When this was done properly, he claimed, a “low-frequency chatter sound could be heard in the earphones.”

That is, the voices of people present in the room during the making of the pot could be re-played from the surface of the pot itself.

[Image: “Laser Cut Record” by Amanda Ghassaei].

[Image: “Laser Cut Record” by Amanda Ghassaei].

Woodbridge suggests that this might have alternative applications: “This is of particular interest as it introduces the possibility of actually recalling and hearing the voices and words of eminent personages as recorded in the paint of their portraits or of famous artists in their pictures.” So an experiment was orchestrated:

With an artist’s brush, paint strokes were applied to the surface of the canvas using “oil” paints involving a variety of plasticities, thicknesses, layers, etc., while martial music was played on the nearby phonograph. Visual examination at low magnification showed that certain strokes had the expected transverse striated appearance. When such strokes, after drying, were gently stroked by the “needle” (small, wooden, spade-like) of the crystal cartridge, at as close to the original stroke speed as possible, short snatches of the original music could be identified.

Through this technique, the overlooked—overlistened?—acoustic qualities of various objects, beyond high-brow pottery and oil paintings, can thus be revealed:

Many situations leading to the possibility of adventitious acoustic recording in past times have been given consideration. These, for example, might consist of scratches, markings, engravings, grooves, chasings, smears, etc., on or in “plastic” materials encompassing metal, wax, wood, bone, mud, paint, crystal, and many others. Artifacts could include objects of personal adornment, sword blades, arrow shafts, pots, engraving plates, paintings, and various items of calligraphic interest.

Woodbridge calls the pursuit and revelation of these sounds “acoustic archaeology.”

[Image: Like the rings of Saturn, from “Laser Cut Record” by Amanda Ghassaei; in fact, perhaps the rings of Saturn are an unread recording…].

[Image: Like the rings of Saturn, from “Laser Cut Record” by Amanda Ghassaei; in fact, perhaps the rings of Saturn are an unread recording…].

But why stop at sounds?

Perhaps in two years’ time, we’ll watch as Amanda Ghassaei cuts DVDs—”the data on a DVD is encoded in the form of small pits and bumps in the track of the disc“—with a combined and simultaneous laser-cutter/3D printer ensemble, coating inscribed “small pits and bumps” with reflective metals.

Suddenly, wood, rock, metal, even exposed geology in situ can host visual content. Indeed, perhaps it already does, but we haven’t invented—or we simply haven’t applied—the right technologies for decoding it. In other words, we have DVD players; we just haven’t, learning from Richard G. Woodbridge III, used them to “read” other materials.

In August 2015, you and some friends hike up to a rock wall in the middle of Utah, and there are DVDs printed all over the surface of the hillside, full-length albums laser-burned into White Rim sandstone, and audio-visual pilgrims carrying deconstructed laser-lens systems, scanning for hidden film fests and warbling soundtracks, swarm every surface all around them.

It’s the rise of geomedia.

[Image: Painting of a lyrebird by John Gould, courtesy archive.org.]

[Image: Painting of a lyrebird by John Gould, courtesy archive.org.]

[Image: “

[Image: “ [Image: “

[Image: “ [Image: “

[Image: “ [Image: Like the rings of Saturn, from “

[Image: Like the rings of Saturn, from “