The work of novelist China Miéville is well-known—and increasingly celebrated—for its urban and architectural imagery.

In his 2000 novel Perdido Street Station, for instance, an old industrial scrapyard on the underside of the city, full of discarded machine parts and used electronic equipment, suddenly bootstraps itself into artificial intelligence, self-rearranging into a tentacular and sentient system. In The Scar, a floating city travels the oceans, lashed together from the hulls of captured ships:

In his 2000 novel Perdido Street Station, for instance, an old industrial scrapyard on the underside of the city, full of discarded machine parts and used electronic equipment, suddenly bootstraps itself into artificial intelligence, self-rearranging into a tentacular and sentient system. In The Scar, a floating city travels the oceans, lashed together from the hulls of captured ships:

They were built up, topped with structure, styles and materials shoved together from a hundred histories and aesthetics into a compound architecture. Centuries-old pagodas tottered on the decks of ancient oarships, and cement monoliths rose like extra smokestacks on paddlers stolen from southern seas. The streets between the buildings were tight. They passed over the converted vessels on bridges, between mazes and plazas, and what might have been mansions. Parklands crawled across clippers, above armories in deeply hidden decks. Decktop houses were cracked and strained from the boats’ constant motion.

In his story “The Rope of the World,” originally published in Icon, a failed space elevator becomes the next Tintern Abbey, an awe-inspiring Romantic ruin in the sky. In “Reports Of Certain Events In London,” from the collection Looking for Jake, Miéville describes how constellations of temporary roads flash in and out through nighttime London, a shifting vascular geography of trap streets, only cataloged by the most fantastical maps.

And in his 2004 novel Iron Council, Miéville imagines something called “slow sculpture,” a geologically sublime new artform by which huge blocks of sandstone are “carefully prepared: shafts drilled precisely, caustic agents dripped in, for a slight and so-slow dissolution of rock in exact planes, so that over years of weathering, slabs would fall in layers, coming off with the rain, and at very last disclosing their long-planned shapes. Slow-sculptors never disclosed what they had prepared, and their art revealed itself only long after their deaths.”

BLDGBLOG has always been interested in learning how novelists see the city—how spatial descriptions of things like architecture and landscape can have compelling effects, augmenting both plot and emotion in ways that other devices, such as characterization, sometimes cannot. In earlier interviews with such writers as Patrick McGrath, Kim Stanley Robinson, Zachary Mason, Jeff VanderMeer, Tom McCarthy, and Mike Mignola, we have looked at everything from the literary appeal and narrative usefulness of specific buildings and building types to the descriptive influence of classical landscape painting, and we have entertained the idea that the demands of telling a good story often give novelists a more subtle and urgent sense of space even than architects and urban planners.

Over the course of the following long interview, China Miéville discusses the conceptual origins of the divided city featured in his recent, award-winning novel The City and The City; he points out the interpretive limitations of allegory, in a craft better served by metaphor; we take a look at the “squid cults” of Kraken (which arrives in paperback later this month) and maritime science fiction, more broadly; the seductive yet politically misleading appeal of psychogeography; J.G. Ballard and the clichés of suburban perversity; the invigorating necessities of urban travel; and much more.

[Image: China Miéville, photographed by Andrew Testa, courtesy of the New York Times].

[Image: China Miéville, photographed by Andrew Testa, courtesy of the New York Times].

• • •BLDGBLOG: I’d like to start with

The City and The City. What was your initial attraction to the idea of a divided city, and how did you devise the specific way in which the city would be split?

China Miéville: I first thought of the divided city as a development from an earlier idea I had for a fantasy story. That idea was more to do with different groups of people who live side-by-side but, because they are different species, relate to the physical environment very, very differently, having different kinds of homes and so on. It was essentially an exaggeration of the way humans and rats live in London, or something similar. But, quite quickly, that shifted, and I began to think about making it simply human.

For a long time, I couldn’t get the narrative. I had the setting reasonably clear in my head and, then, once I got that, a lot of things followed. For example, I knew that I didn’t want to make it narrowly, allegorically reductive, in any kind of lumpen way. I didn’t want to make one city heavy-handedly Eastern and one Western, or one capitalist and one communist, or any kind of nonsense like that. I wanted to make them both feel combined and uneven and real and full-blooded. I spent a long time working on the cities and trying to make them feel plausible and half-remembered, as if they were uneasily not quite familiar rather than radically strange.

I auditioned various narrative shapes for the book and, eventually, after a few months, partly as a present to my Mum, who was a big crime reader, and partly because I was reading a lot of crime at the time and thinking about crime, I started realizing what was very obvious and should have been clear to me much earlier. That’s the way that noir and hard-boiled and crime procedurals, in general, are a kind of mythic urbanology, in a way; they relate very directly to cities.

Once I’d thought of that, exaggerating the trope of the trans-jurisdictional police problem—the cops who end up having to be on each other’s beats—the rest of the novel just followed immediately. In fact, it was difficult to imagine that I hadn’t been able to work it out earlier. That was really the genesis.

I should say, also, that with the whole idea of a divided city there are analogies in the real world, as well as precursors within fantastic fiction. C. J. Cherryh wrote a book that had a divided city like that, in some ways, as did Jack Vance. Now I didn’t know this at the time, but I’m also not getting my knickers in a twist about it. If you think what you’re trying to do is come up with a really original idea—one that absolutely no one has ever had before—you’re just kidding yourself.

You’re inevitably going to tread the ground that the greats have trodden before, and that’s fine. It simply depends on what you’re able to do with it.

BLDGBLOG: Something that struck me very strongly about the book was that you manage to achieve the feel of a fantasy or science fiction story simply through the description of a very convoluted political scenario. The book doesn’t rely on monsters, non-humans, magical technologies, and so on; it’s basically a work of political science fiction.

BLDGBLOG: Something that struck me very strongly about the book was that you manage to achieve the feel of a fantasy or science fiction story simply through the description of a very convoluted political scenario. The book doesn’t rely on monsters, non-humans, magical technologies, and so on; it’s basically a work of political science fiction.

Miéville: This is impossible to talk about without getting into spoiler territory—which is fine, I don’t mind that—but we should flag that right now for anyone who hasn’t read it and does want to read it.

But, yes, the overtly fantastical element just ebbed and ebbed, becoming more suggestive and uncertain. Although it’s written in such a way that there is still ambiguity—and some readers are very insistent on focusing on that ambiguity and insisting on it—at the same time, I think it’s a book, like all of my books, for which, on the question of the fantastic, you might want to take a kind of Occam’s razor approach. It’s a book that has an almost contrary relation to the fantastic, in a certain sense.

[Image: The marbled intra-national sovereignties of Baarle-Hertog].

[Image: The marbled intra-national sovereignties of Baarle-Hertog].

BLDGBLOG: In some ways, it’s as if The City and The City simply describes an exaggerated real-life border condition, similar to how people live in Jerusalem or the West Bank, Cold War Berlin or contemporary Belfast—or even in a small town split by the U.S./Canada border, like Stanstead-Derby Line. In a sense, these settlements consist of next-door neighbors who otherwise have very complicated spatial and political relationships to one another. For instance, I think I sent you an email about a year ago about a town located both on and between the Dutch-Belgian border, called Baarle-Hertog.

Miéville: You did!

BLDGBLOG: I’m curious to what extent you were hoping to base your work on these sorts of real-life border conditions.

Miéville: The most extreme example of this was something I saw in an article in the Christian Science Monitor, where a couple of poli-sci guys from the State Department or something similar were proposing a solution to the Arab-Israeli conflict. In the case of Jerusalem, they were proposing basically exactly this kind of system, from The City and The City, in that you would have a single urban space in which different citizens are covered by completely different juridical relations and social relations, and in which you would have two overlapping authorities.

I was amazed when I saw this. I think, in a real world sense, it’s completely demented. I don’t think it would work at all, and I don’t think Israel has the slightest intention of trying it.

My intent with The City and The City was, as you say, to derive something hyperbolic and fictional through an exaggeration of the logic of borders, rather than to invent my own magical logic of how borders could be. It was an extrapolation of really quite everyday, quite quotidian, juridical and social aspects of nation-state borders: I combined that with a politicized social filtering, and extrapolated out and exaggerated further on a sociologically plausible basis, eventually taking it to a ridiculous extreme.

But I’m always slightly nervous when people make analogies to things like Palestine because I think there can be a danger of a kind of sympathetic magic: you see two things that are about divided cities and so you think that they must therefore be similar in some way. Whereas, in fact, in a lot of these situations, it seems to me that—and certainly in the question of Palestine—the problem is not one population being unseen, it’s one population being very, very aggressively seen by the armed wing of another population.

In fact, I put those words into Borlu’s mouth in the book, where he says, “This is nothing like Berlin, this is nothing like Jerusalem.” That’s partly just to disavow—because you don’t want to make the book too easy—but it’s also to make a serious point, which is that, obviously, the analogies will occur but sometimes they will obscure as much as they illuminate.

[Image: The international border between the U.S. and Canada passes through the center of a library; photo courtesy of the Center for Land Use Interpretation. “Technically, any time anyone crosses the international line, they are subject to having to report, in person, to a port of entry inspection station for the country they are entering,” CLUI explains. “Visiting someone on the other side of the line, even if the building is next door, means walking around to the inspection station first, or risk being an outlaw. Playing catch on Maple Street/Rue Ball would be an international event, and would break no laws presumably, so long as each time the ball was caught, the recipient marched over to customs to declare the ball.”].

[Image: The international border between the U.S. and Canada passes through the center of a library; photo courtesy of the Center for Land Use Interpretation. “Technically, any time anyone crosses the international line, they are subject to having to report, in person, to a port of entry inspection station for the country they are entering,” CLUI explains. “Visiting someone on the other side of the line, even if the building is next door, means walking around to the inspection station first, or risk being an outlaw. Playing catch on Maple Street/Rue Ball would be an international event, and would break no laws presumably, so long as each time the ball was caught, the recipient marched over to customs to declare the ball.”].

BLDGBLOG: Your books often lend themselves to political readings, on the other hand. Do you write with specific social or political allegories in mind, and, further, how do your settings—as in The City and The City—come to reflect political intentions, spatially?

Miéville: My short answer is that I dislike thinking in terms of allegory—quite a lot. I’ve disagreed with Tolkien about many things over the years, but one of the things I agree with him about is this lovely quote where he talks about having a cordial dislike for allegory.

The reason for that is partly something that Frederic Jameson has written about, which is the notion of having a master code that you can apply to a text and which, in some way, solves that text. At least in my mind, allegory implies a specifically correct reading—a kind of one-to-one reduction of the text.

It amazes me the extent to which this is still a model by which these things are talked about, particularly when it comes to poetry. This is not an original formulation, I know, but one still hears people talking about “what does the text mean?”—and I don’t think text means like that. Texts do things.

I’m always much happier talking in terms of metaphor, because it seems that metaphor is intrinsically more unstable. A metaphor fractures and kicks off more metaphors, which kick off more metaphors, and so on. In any fiction or art at all, but particularly in fantastic or imaginative work, there will inevitably be ramifications, amplifications, resonances, ideas, and riffs that throw out these other ideas. These may well be deliberate; you may well be deliberately trying to think about issues of crime and punishment, for example, or borders, or memory, or whatever it might be. Sometimes they won’t be deliberate.

But the point is, those riffs don’t reduce. There can be perfectly legitimate political readings and perfectly legitimate metaphoric resonances, but that doesn’t end the thing. That doesn’t foreclose it. The text is not in control. Certainly the writer is not in control of what the text can do—but neither, really, is the text itself.

So I’m very unhappy about the idea of allegoric reading, on the whole. Certainly I never intend my own stuff to be allegorical. Allegories, to me, are interesting more to the extent that they fail—to the extent that they spill out of their own bounds. Reading someone like George MacDonald—his books are extraordinary—or Charles Williams. But they’re extraordinary to the extent that they fail or exceed their own intended bounds as Christian allegory.

When Iron Council came out, people would say to me: “Is this book about the Gulf War? Is this book about the Iraq War? You’re making a point about the Iraq War, aren’t you?” And I was always very surprised. I was like, listen: if I want to make a point about the Iraq War, I’ll just say what I think about the Iraq War. I know this because I’ve done it. I write political articles. I’ve written a political book. But insisting on that does not mean for a second that I’m saying—in some kind of unconvincing, “cor-blimey, I’m just a story-teller, guvnor,” type-thing—that these books don’t riff off reality and don’t have things to say about it.

There’s this very strange notion that a writer needs to smuggle these other ideas into the text, but I simply don’t understand why anyone would think that that’s what fiction is for.

BLDGBLOG: There are also very basic historical and referential limits to how someone might interpret a text allegorically. If Iron Council had been written twenty years from now, for instance, during some future war between Taiwan and China, many readers would think it was a fictional exploration of that, and they’d forget about the Iraq War entirely.

Miéville: Sure. And you don’t want to disavow these readings. You may think, at this point in this particular book, I actually do want to make a genuine policy prescription. With my hand on my heart, I don’t think I have ever done that, but, especially if you write with a political texture, you certainly have to take readings like this on the chin.

So, when people say: are you really talking about this? My answer is generally not no—it’s generally yes, but… Or yes, and… Or yes… but not in the way that you mean.

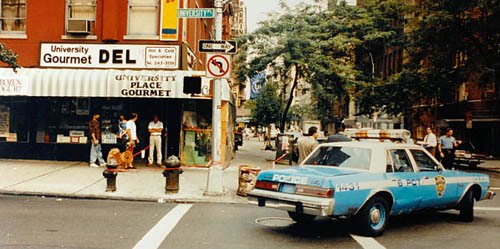

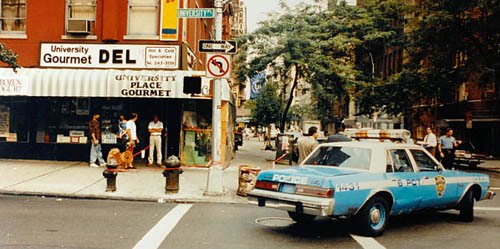

[Image: “The way a cop inhabits the city is doubtless a fascinating thing…” Photo courtesy of the NYPD].

[Image: “The way a cop inhabits the city is doubtless a fascinating thing…” Photo courtesy of the NYPD].

BLDGBLOG: Let’s go back to the idea of the police procedural. It’s intriguing to compare how a police officer and a novelist might look at the city—the sorts of details they both might notice or the narratives they both might pick up on. Broadly speaking, each engages in detection—a kind of hermeneutics of urban space. How did this idea of urban investigation—the “mythic urbanology” you mentioned earlier—shape your writing of The City and The City?

Miéville: On the question of the police procedural and detection, for me, the big touchstones here were detective fiction, not real police. Obviously they are related, but they’re related in a very convoluted, mediated way.

What I wanted to do was write something that had a great deal of fidelity—hopefully not camp fidelity, but absolute rigorous fidelity—to certain generic protocols of policing and criminology. That was the drive, much more than trying to find out how police really do their investigations. The way a cop inhabits the city is doubtless a fascinating thing, but what was much more important to me for this book was the way that the genre of crime, as an aesthetic field, relates to the city.

The whole notion of decoding the city—the notion that, in a crime drama, the city is a text of clues, in a kind of constant, quantum oscillation between possibilities, with the moment of the solution really being a collapse and, in a sense, a kind of tragedy—was really important to me.

Of course, I’m not one of those writers who says I don’t read reviews. I do read reviews. I know that some readers were very dissatisfied with the strict crime drama aspect of it. I can only hold up my hands. It was extremely strict. I don’t mean to do that kind of waffley, unconvincing, writerly, carte blanche, get-out-clause of “that was the whole point.” Because you can have something very particular in mind and still fuck it up.

But, for me, given the nature of the setting, it was very important to play it absolutely straight, so that, having conceived of this interweaving of the cities, the actual narrative itself would remain interesting, and page-turning, and so on and so forth. I wanted it to be a genuine who-dunnit. I wanted it to be a book that a crime reader could read and not have a sense that I had cheated.

By the way, I love that formulation of crime-readers: the idea that a book can cheat is just extraordinary.

BLDGBLOG: Can you explain what you mean, in this context, by being rigorous? You were rigorous specifically to what?

Miéville: The book walks through three different kinds of crime drama. In section one and section two, it goes from the world-weary boss with a young, chippy sidekick to the mismatched partners who end up with grudging respect for each other. Then, in part three, it’s a political conspiracy thriller. I quite consciously tried to inhabit these different iterations of crime writing, as a way to explore the city.

But this has all just been a long-winded way of saying that I would not pretend or presume any kind of real policing knowledge of the way cities work. I suspect, probably, like most things, actual genuine policing is considerably less interesting than it is in its fictionalized version—but I honestly don’t know.

[Images: New York City crime scene photographs].

[Images: New York City crime scene photographs].

BLDGBLOG: There’s a book that came out a few years ago called The Meadowlands, by Robert Sullivan. At one point, Sullivan tags along with a retired detective in New Jersey who reveals that, now that he’s retired, he no longer really knows what to do with all the information he’s accumulated about the city over the years. Being retired means he basically knows thousands of things about the region that no longer have any real use for him. He thus comes across as a very melancholy figure, almost as if all of it was supposed to lead up to some sort of narrative epiphany—where he would finally and absolutely understand the city—but then retirement came along and everything went back to being slightly pointless. It was an interpretive comedown, you might say.

Miéville: That kind of specialized knowledge, in any field, can be intoxicating. If you experience a space—say, a museum—with a plumber, you may well come out with a different sense of the strengths and weaknesses of that museum—considering the pipework, as well, of course, as the exhibits—than otherwise. This is one reason I love browsing specialist magazines in fields about which I know nothing.

Obviously, then, with something that is explicitly concerned with uncovering and solving, it makes perfect sense that seeing the city through the eyes of a police detective would give you a very self-conscious view of what’s happening out there.

In terms of fiction, though, I think, if anything, the drive is probably the opposite. Novelists have an endless drive to aestheticize and to complicate. I know there’s a very strong tradition—a tradition in which I write, myself—about the decoding of the city. Thomas de Quincey, Michael Moorcock, Alan Moore, Neil Gaiman, Iain Sinclair—that type-thing. The idea that, if you draw the right lines across the city, you’ll find its Kabbalistic heart and so on.

The thing about that is that it’s intoxicating—but it’s also bullshit. It’s bullshit and it’s paranoia—and it’s paranoia in a kind of literal sense, in that it’s a totalizing project. As long as you’re constantly aware of that, at an aesthetic level, then it’s not necessarily a problem; you’re part of a process of urban mythologization, just like James Joyce was, I suppose. But the sense that this notion of uncovering—of taking a scalpel to the city and uncovering the dark truth—is actually real, or that it actually solves anything, and is anything other than an aesthetic sleight of hand, can be quite misleading, and possibly even worse than that. To the extent that those texts do solve anything, they only solve mysteries that they created in the first place, which they scrawled over the map of a mucky contingent mess of history called the city. They scrawled a big question mark over it and then they solved it.

Arthur Machen does this as well. All the great weird fiction city writers do it. Machen explicitly talks about the strength of London, as opposed to Paris, in that London is more chaotic. Although he doesn’t put it in these words, I think what partly draws him to London is this notion that, in the absence of a kind of unifying vision, like Haussmann’s Boulevards, and in a city that’s become much more syncretic and messy over time, you have more room to insert your own aestheticizing vision.

As I say, it’s not in and of itself a sin, but to think of this as a real thing—that it’s a lived political reality or a new historical understanding of the city—is, I think, a misprision.

BLDGBLOG: You can see this, as well, in the rise of psychogeography—or, at least, some popular version of it—as a tool of urban analysis in architecture today. This popularity often fails to recognize that, no matter how fun or poetic an experience it genuinely might be, randomly wandering around Boston with an iPhone, for instance, is not guaranteed to produce useful urban insights.

Miéville: Some really interesting stuff has been done with psychogeography—I’m not going to say it’s without uses other than for making pretty maps. I mean, re-experiencing lived urban reality in ways other than how one is more conventionally supposed to do so can shine a new light on things—but that’s an act of political assertion and will. If you like, it’s a kind of deliberate—and, in certain contexts, radical—misunderstanding. Great, you know—good on you! You’ve productively misunderstood the city. But I think that the bombast of these particular—what are we in now? fourth or fifth generation?—psychogeographers is problematic.

Presumably at some point we’re going to get to a stage, probably reasonably soon, in which someone—maybe even one of the earlier generation of big psychogeographers—will write the great book against psychogeography. Not even that it’s been co-opted—it’s just wheel-spinning.

BLDGBLOG: In an interview with Ballardian, Iain Sinclair once joked that psychogeography, as a term, has effectively lost all meaning. Now, literally any act of walking through the city—walking to work in the morning, walking around your neighborhood, walking out to get a bagel—is referred to as “psychogeography.” It’s as if the experience of being a pedestrian in the city has become so unfamiliar to so many people, that they now think the very act of walking around makes them a kind of psychogeographic avant-garde.

Miéville: It’s no coincidence, presumably, that Sinclair started wandering out of the city and off into fields.

[Image: Art by Vincent Chong for the Subterranean Press edition of Kraken].

[Image: Art by Vincent Chong for the Subterranean Press edition of Kraken].

BLDGBLOG: This brings us to something I want to talk about from Kraken, which comes out in paperback here in the States next week. In that book, you describe a group of people called the Londonmancers. They’re basically psychogeographers with a very particular, almost parodically mystical understanding of the city. How does Kraken utilize this idea of an occult geography of greater London?

Miéville: Yes, this relates directly to what we were just saying. For various reasons, some cities refract, through aesthetics and through art, with a particular kind of flamboyancy. For whatever reason, London is one of them. I don’t mean to detract from all the other cities in the world that have their own sort of Gnosticism, but it is definitely the case that London has worked particularly well for this. There are a couple of moments in the book of great sentimentality, as well, written, I think, when I was feeling very, very well disposed toward London.

I think, in those terms, that I would locate myself completely in the tradition of London phantasmagoria. I see myself as very much doing that kind of thing. But, at the same time, as the previous answer showed, I’m also rather ambivalent to it and sort of impatient with it—probably with the self-hating zeal of someone who recognizes their own predilections!

Kraken, for me, in a relatively light-hearted and comedic form, is my attempt to have it both ways: to both be very much in that tradition and also to take the piss out of it. Reputedly, throughout Kraken, the very act of psychogeographic enunciation and urban uncovering is both potentially an important plot point and something that does uncover a genuine mystery; but it is also something that is ridiculous and silly, an act of misunderstanding. It’s all to do with what Thomas Pynchon, in Gravity’s Rainbow, called kute korrespondences: “hoping to zero in on the tremendous and secret Function whose name, like the permuted names of God, cannot be spoken.”

The London within Kraken feels, to me, much more dreamlike than the London of something like King Rat. That’s obviously a much earlier book, and I now write very differently; but King Rat, for all its flaws, is a book very much to do with its time. It’s not just to do with London; it’s to do with London in the mid-nineties. It’s a real, particular London, phantasmagorized.

But Kraken is also set in London—and I wanted to indulge all my usual Londonisms and take them to an absurd extreme. The idea, for example, as you say, of this cadre of mages called the Londonmancers: that’s both in homage to parts of that tradition, and also, hopefully, an extension of it to a kind of absurdity—the ne plus ultra, you know?

BLDGBLOG: Kraken also makes some very explicit maritime gestures—the squid, of course, which is very redolent of H.P. Lovecraft, but also details such as the pirate-like duo of Goss and Subby. This maritime thread pops up, as well, in The Scar, with its floating city of linked ships. My question is: how do your interests in urban arcana and myth continue into the sphere of the maritime, and what narrative or symbolic possibilities do maritime themes offer your work?

Miéville: Actually, I think I was very restrained about Lovecraft. I think the book mentions Cthulhu twice—which, for a 140,000 or 150,000-word novel about giant squid cults, is pretty restrained! That’s partly because, as you say, if you write a book about a tentacular monster with a strange cult associated with it, anyone who knows the field is going to be thinking immediately in terms of Lovecraft. And I’m very, very impressed by Lovecraft—he’s a big presence for me—but, partly for that very reason, I think Kraken is one of the least Lovecrafty things I’ve done.

As to the question of maritimism, like a lot of my interests, it’s more to do with how it has been filtered through fiction, rather than how it is in reality. In reality, I have no interest in sailing. I’ve done it, I think, once.

But maritime fiction, from Gulliver’s Travels onward, I absolutely love. I love that it has its own set of traditions; in some ways, it’s a kind of mini-canon. It has its own riffs. There are some lovely teasings of maritime fiction within Gulliver’s Travels where he gets into the pornography of maritime terminology: mainstays and capstans and mizzens and so on, which, again, feature quite prominently in The Scar.

[Image: “An Imaginary View of the Arsenale” by J.M.W. Turner, courtesy of the Tate].

[Image: “An Imaginary View of the Arsenale” by J.M.W. Turner, courtesy of the Tate].

BLDGBLOG: In the context of the maritime, I was speaking to Reza Negarestani recently and he mentioned a Russian novella from the 1970s called “The Crew Of The Mekong,” suggesting that I ask you about your interest in it. Reza, of course, wrote Cyclonopedia, which falls somewhere between, say, H.P. Lovecraft and ExxonMobil, and for which you supplied an enthusiastic endorsement.

Miéville: Yes, I was blown away by Reza’s book—partly just because of the excitement of something that seems genuinely unclassifiable. It really is pretty much impossible to say whether you’re reading a work of genre fiction or a philosophical textbook or both of the above. There’s also the slightly crazed pseudo-rigor of it, and the sense that this is philosophy as inspired by schlocky horror movies as much as by Alain Badiou.

There’s a phrase that Kim Newman uses: post-genre horror. It’s a really nice phrase for something which is clearly inflected in a horror way, and clearly emerges out of the generic tradition of horror, but is no longer reducible to it. I think that Reza’s work is a very, very good example of that. As such, Cyclonopedia is one of my favorite books of the last few years.

BLDGBLOG: So Reza pointed me to “The Crew of the Mekong,” a work of Russian maritime scifi. The authors describe it, somewhat baroquely, as “an account of the latest fantastic discoveries, happenings of the eighteenth century, mysteries of matter, and adventures on land and at sea.” What drew you to it?

Miéville: I can’t remember exactly what brought me to it, to be perfectly honest: it was in a secondhand bookshop and I bought it because it looked like an oddity.

It’s very odd in terms of the shape of its narrative; it sort of lurches, with a story within a story, including a long, extended flashback within the larger framing narrative, and it’s all wrapped up in this pulp shell. In terms of the story itself, if I recall, it was actually me who suggested it to Reza because it has loads of stuff in it about oil, plastic resins, and pipelines, and one of the characters works for an institute called the Institute of Surfaces, which deals with the weird physics and uncanny properties of surfaces and topology.

Some of the flashback scenes and some of the background I’ve seen described as proto-steampunk, which I think is highly anachronistic: it’s more of an elective affinity, that, if you like retro-futurity, you might also like this. At a bare minimum, it’s a book worth reading simply because it’s very odd; at a maximum, some of the things going on it are philosophically interesting, although in a bizarre way.

But foreign pulp always has that peculiar kind of feeling to it, because you have a distinct cultural remove. At its worst, that can lead to an awful kind of orientalism, but it’s undeniably fascinating as a reader.

BLDGBLOG: It’s interesting that depictions of maritime journeys can maintain such strong mythic and imaginative resonance, even across wildly different cultures, eras, genres, and artforms—whether it’s “The Crew of the Mekong” or The Scar, Valhalla Rising or Moby Dick.

Miéville: The maritime world in general is an over-determined symbol of pretty much anything you want it to be—just fill in the blank: yearning, manifest destiny, whatever. It’s a very fecund field. My own interest in it comes pretty much through fiction and, to a certain extent, art. I wish I had a bit more money, in fact, because I would buy a lot of those fairly cheap, timeless, uncredited, late 19th-century, early 20th-century seascapes that you see on sale in a lot of thrift shops.

You also mentioned Goss and Subby. Goss and Subby themselves I never thought of as pirates, in fact. They were my go at iterating the much-masticated trope of the freakishly monstrous duo, figures who are, in some way that I suspect is politically meaningful, and that one day I’ll try to parse, generally even worse than their boss. They often speak in a somewhat odd, stilted fashion, like Hazel and Cha-Cha, or Croup and Vandemar, or various others. The magisterial TV Tropes has a whole entry on such duos called “Those Two Bad Guys.” The tweak that I tried to add with Goss and Subby was to integrate an idea from a Serbian fairy-tale called—spoiler!—“BasCelik.” For anyone who knows that story, this is a big give-away.

Again, though, I think you have to ration your own predilections. I have always been very faithful to my own loves: I look at my notebooks or bits of paper from when I was four and, basically, my interests haven’t changed. Left to my own devices, I would probably write about octopuses, monsters, occasionally Tarzan, and that’s really it. From a fairly young age, the maritime yarn was one of those.

But you can’t just give into your own drives, or you simply end up writing the same book again and again.

[Image: Mapping old London].

[Image: Mapping old London].

BLDGBLOG: Along those lines, are there any settings or environments—or even particular cities—that would be a real challenge for you to work with? Put another way, can you imagine giving yourself a deliberate challenge to write a novel set out in the English suburbs, or even in a place like Los Angeles? How might that sort of unfamiliar, seemingly very un-Miéville-like landscape affect your plots and characters?

Miéville: That’s a very interesting question. I really like that approach, in terms of setting yourself challenges that don’t come naturally. It’s almost a kind of Oulipo approach. It’s tricky, though, because you have to find something that doesn’t come naturally, but, obviously, you don’t want to write about something that doesn’t interest you. It has to be something that interests you contradictorally, or contrarily.

To be honest, the suburbs don’t attract me, for a bunch of reasons. I think it’s been done to death. I think anyone who tried to do that after J. G. Ballard would be setting themselves up for failure. As I tried to say when I did my review of the Ballard collection for The Nation, one of the problems is that, with an awful lot of suburban art today, it is pitched as this tremendously outré and radical claim to say that the suburbs are actually hotbeds of perversity—whereas, in fact, that is completely the cliché now. If you wanted to do something interesting, you would have to write about terribly boring suburbs, which would loop all the way back round again, out of interesting, through meta-interesting, and back down again to boring. So I doubt I would do something set in the suburbs.

I am quite interested in wilderness. Iron Council has quite a bit of wilderness, and that was something that I really liked writing and that I’d like to try again.

But, to be honest, it’s different kinds of urban space that appeal to me. If you’re someone who can’t drive, like I can’t, you find a lot of American cities are not just difficult, but really quite strange. I spend a lot of time in Providence, Rhode Island, and it’s a nice town, but it just doesn’t operate like a British town. A lot of American towns don’t. The number of American cities where downtown is essentially dead after seven o’clock, or in which you have these strange little downtowns, and then these quite extensive, sprawling but not quite suburban surroundings that all call themselves separate cities, that segue into each other and often have their own laws—that sort of thing is a very, very strange urban political aesthetic to me.

I’ve been thinking about trying to write a story not just set, for example, in Providence, but in which Providence, or another city that operates in a very non-English—or non-my-English—fashion, is very much part of the structuring power of the story. I’d be interested in trying something like that.

But countries all around the world have their own specificities about the way their urban environments work. I was in India recently, for example. It was a very brief trip, and I’m sure some of this was just wish fulfillment or aesthetic speculation, but I became really obsessed with the way, the moment you touched down at a different airport, you got out and you breathed the air, Mumbai felt different to Delhi, felt different to Kolkata, felt different to Chennai.

Rather than syncretizing a lot of those elements, I’d like to try to be really, really faithful to one or another city, which is not my city, in the hopes that, being an outsider, I might notice certain aspects that otherwise one would not. There’s a certain type of ingenuous everyday inhabiting of a city, which is very pre-theoretical for something like psychogeography, but it brings its own insights, particularly when it doesn’t come naturally or when it goes wrong.

There’s a lovely phrase that I think Algernon Blackwood used to describe someone’s bewilderment: he describes him as being bewildered in the way a man is when he’s looking for a post box in a foreign city. It’s a completely everyday, quotidian thing, and he might walk past it ten times, but he doesn’t—he can’t—recognize it.

That kind of very, very low-level alienation—the uncertainty about how do you hail a taxi, how do you buy food in this place, if somebody yells something from their top window, why does everyone move away from this part of the street and not that part? It’s that kind of very low-level stuff, as opposed to the kind of more obvious, dramatic differences, and I think there might be a way of tapping into that knowledge, knowledge that the locals don’t even think to tell you, that might be an interesting way in.

To that extent, it would be cities that I like but in which I’m very much an outsider that I’d like to try to tap.

• • •Thanks to

China Miéville for finding time to have this conversation, including scheduling a phone call at midnight in order to wrap up the final questions. Thanks, as well, to

Nicola Twilley, who transcribed 95% of this interview and offered editorial feedback while it was in process, and to

Tim Maly who first told me about the towns of Derby Line–Stanstead.

Miéville’s newest book, Embassytown, comes out in the U.S. in May; show your support for speculative fiction and pre-order a copy soon. If you are new to Miéville’s work, meanwhile, I might suggest starting with The City and The City.

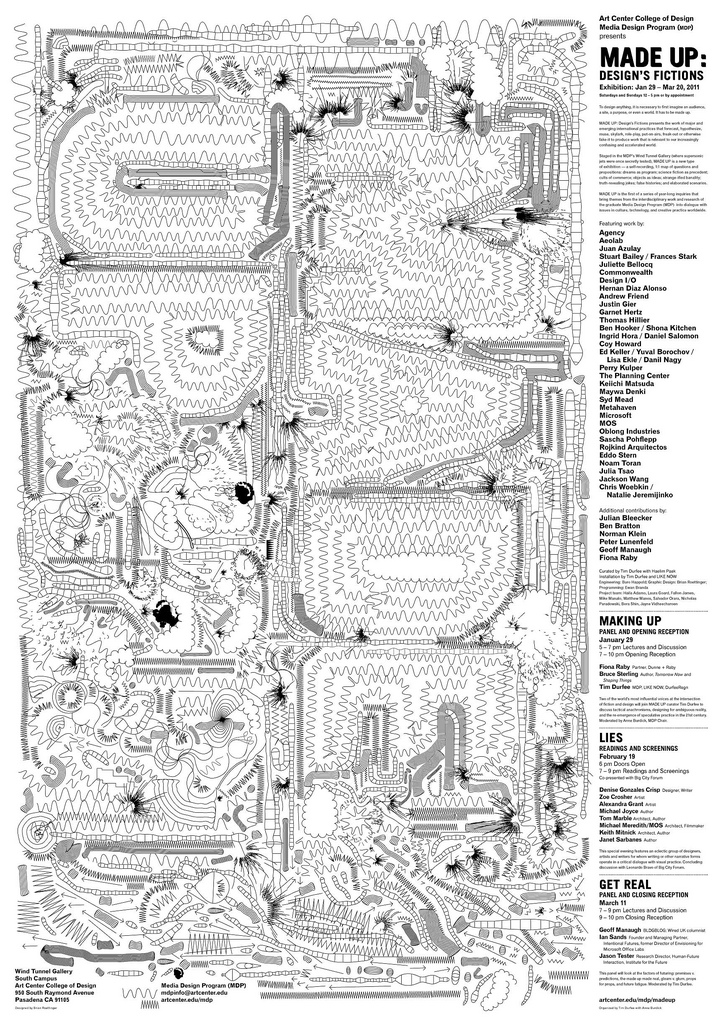

[Image: The poster, designed by Brian Roettinger, for MADE UP: Design’s Fictions; view larger].

[Image: The poster, designed by Brian Roettinger, for MADE UP: Design’s Fictions; view larger].

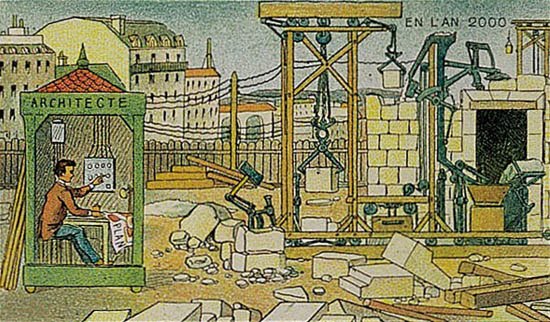

[Image: The architect and his construction robots by

[Image: The architect and his construction robots by  [Image: Courtesy of

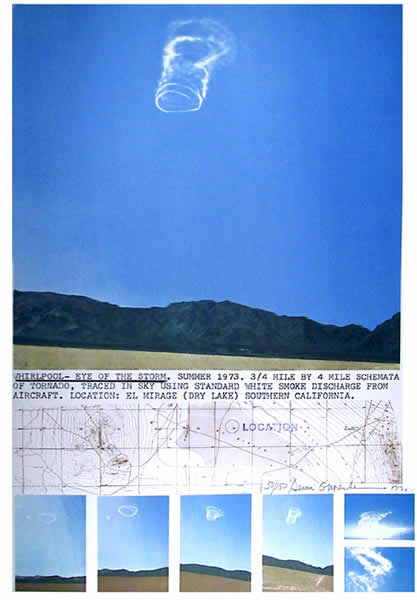

[Image: Courtesy of  [Image: “Pike Loop” (2009) by

[Image: “Pike Loop” (2009) by

[Image: “

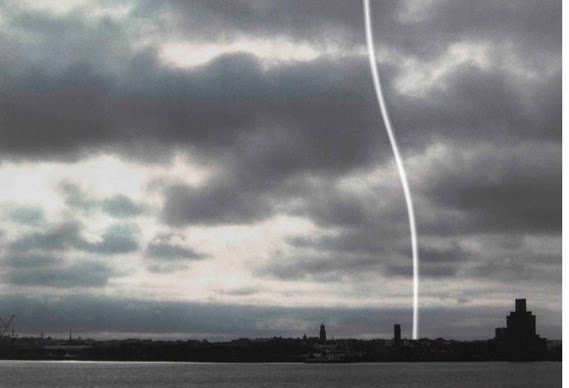

[Image: “ [Image: “Column” by Anthony McCall, courtesy of

[Image: “Column” by Anthony McCall, courtesy of

In his 2000 novel

In his 2000 novel  [Image: China Miéville, photographed by

[Image: China Miéville, photographed by  BLDGBLOG: Something that struck me very strongly about the book was that you manage to achieve the feel of a fantasy or science fiction story simply through the description of a very convoluted political scenario. The book doesn’t rely on monsters, non-humans, magical technologies, and so on; it’s basically a work of political science fiction.

BLDGBLOG: Something that struck me very strongly about the book was that you manage to achieve the feel of a fantasy or science fiction story simply through the description of a very convoluted political scenario. The book doesn’t rely on monsters, non-humans, magical technologies, and so on; it’s basically a work of political science fiction.  [Image: The marbled intra-national sovereignties of

[Image: The marbled intra-national sovereignties of  [Image: The international border between the U.S. and Canada passes through the center of a library; photo courtesy of the

[Image: The international border between the U.S. and Canada passes through the center of a library; photo courtesy of the  [Image: “The way a cop inhabits the city is doubtless a fascinating thing…” Photo courtesy of the

[Image: “The way a cop inhabits the city is doubtless a fascinating thing…” Photo courtesy of the

[Images: New York City crime scene photographs].

[Images: New York City crime scene photographs].  [Image: Art by Vincent Chong for the Subterranean Press edition of

[Image: Art by Vincent Chong for the Subterranean Press edition of  [Image: “An Imaginary View of the Arsenale” by J.M.W. Turner, courtesy of the

[Image: “An Imaginary View of the Arsenale” by J.M.W. Turner, courtesy of the  [Image: Mapping old London].

[Image: Mapping old London].

[Image: Constructing with BeadBricks by Rizal Muslimin, courtesy of

[Image: Constructing with BeadBricks by Rizal Muslimin, courtesy of

[Images: BeadBricks by Rizal Muslimin, courtesy of

[Images: BeadBricks by Rizal Muslimin, courtesy of  [Image: Constructing with BeadBricks by Rizal Muslimin, courtesy of

[Image: Constructing with BeadBricks by Rizal Muslimin, courtesy of  [Image: The EcoCeramic Masonry System by Kelly Winn and Jason Vollen, courtesy of

[Image: The EcoCeramic Masonry System by Kelly Winn and Jason Vollen, courtesy of

[Images: The EcoCeramic Masonry System by Kelly Winn and Jason Vollen, courtesy of

[Images: The EcoCeramic Masonry System by Kelly Winn and Jason Vollen, courtesy of

[Image: By

[Image: By  [Image: By

[Image: By

[Image: From the forthcoming

[Image: From the forthcoming  [Images: From the forthcoming

[Images: From the forthcoming  [Images: From the forthcoming

[Images: From the forthcoming  [Images: From the forthcoming

[Images: From the forthcoming

[Images: Derelict landscapes and optical devices scaled up to the size of megastructures, by

[Images: Derelict landscapes and optical devices scaled up to the size of megastructures, by  [Images: From the forthcoming

[Images: From the forthcoming

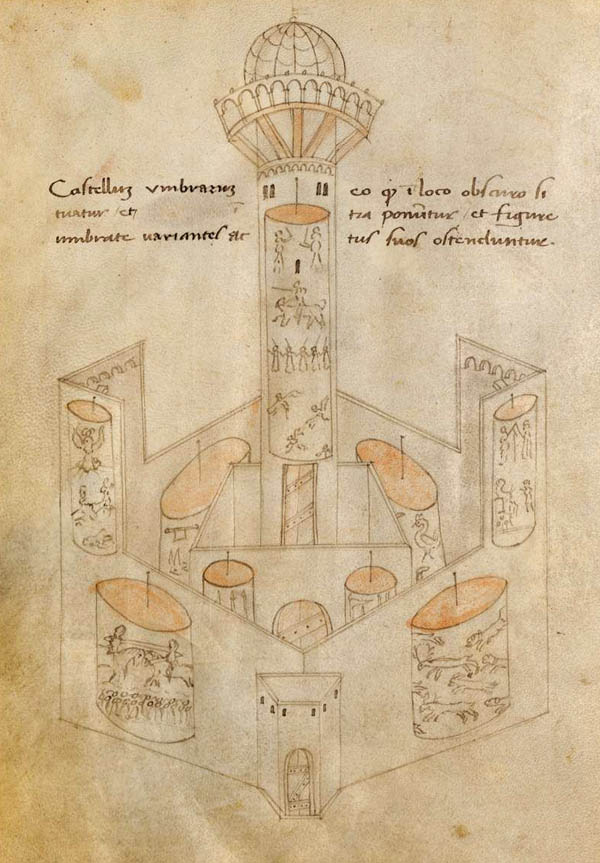

[Image: Giovanni Fontana’s 15th-century “castle of shadows,” from a paper by

[Image: Giovanni Fontana’s 15th-century “castle of shadows,” from a paper by

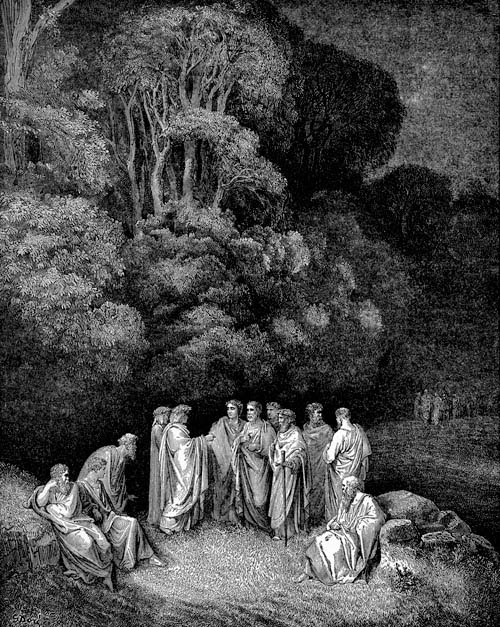

[Image: “

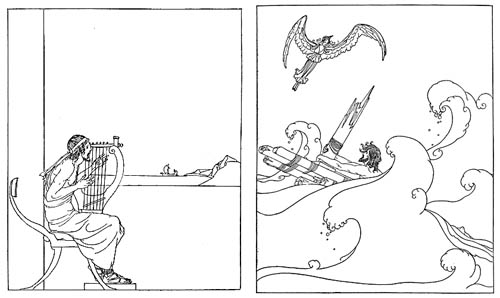

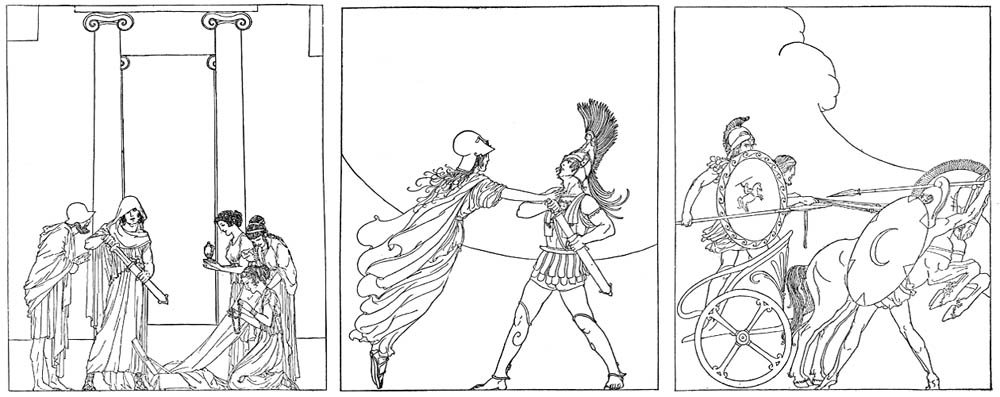

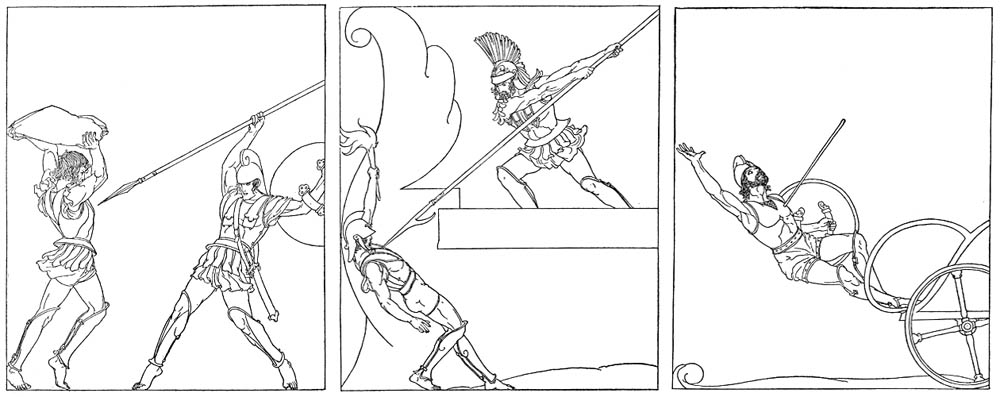

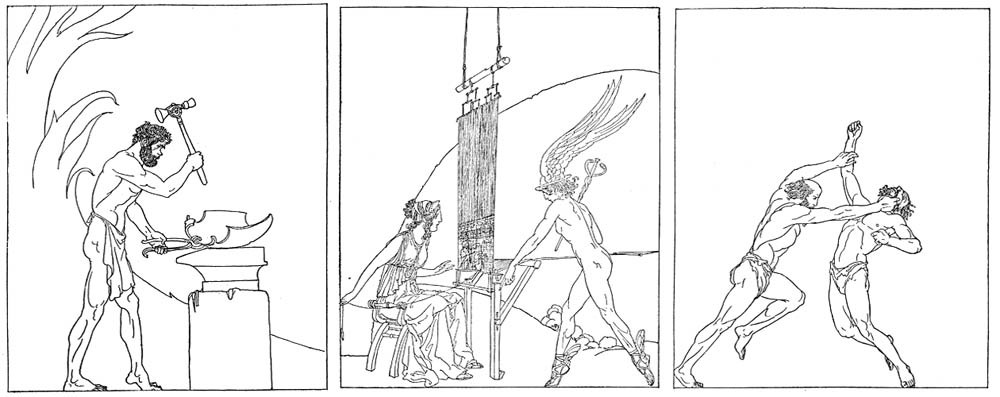

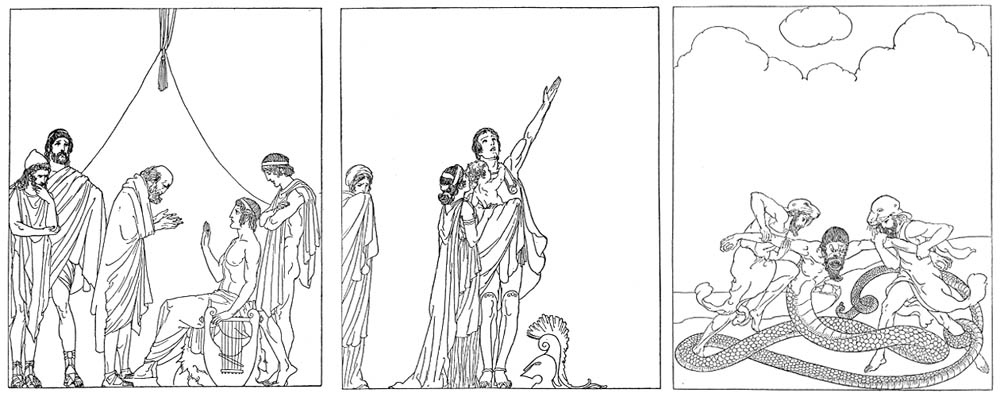

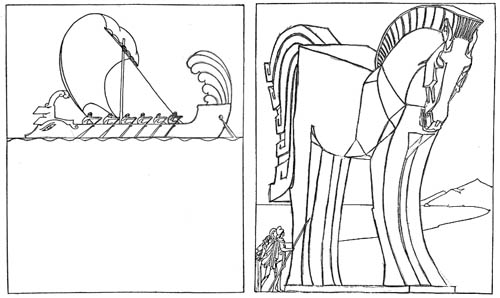

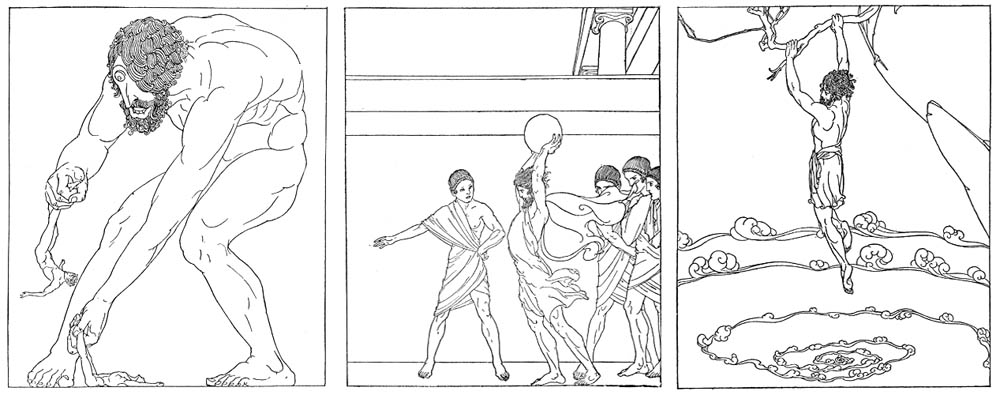

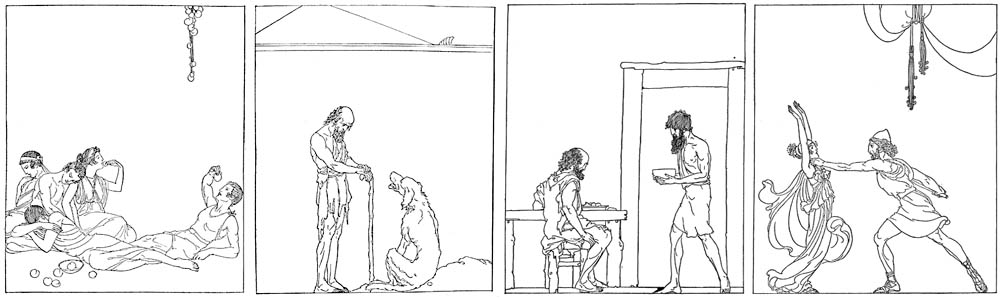

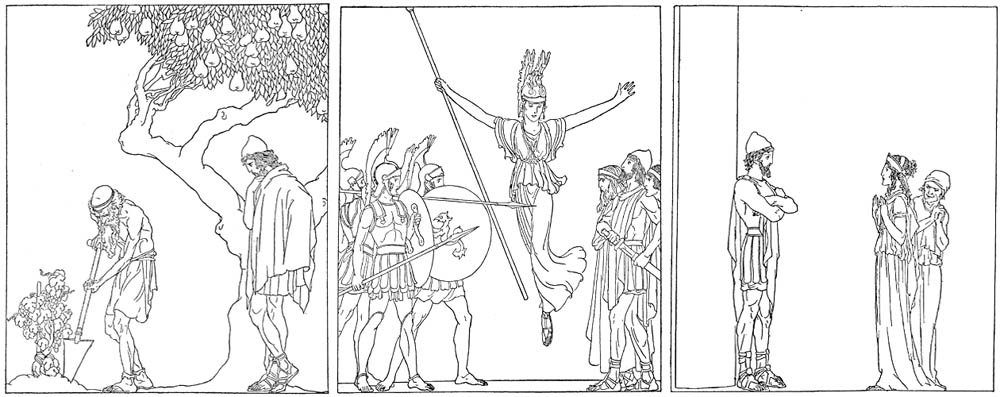

[Image: “ [Images: Illustrations by Willy Pogány for

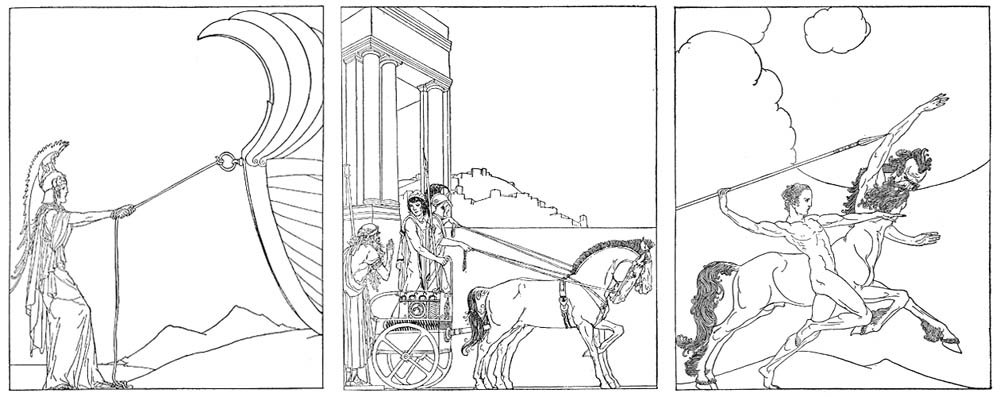

[Images: Illustrations by Willy Pogány for  [Images: Illustrations by Willy Pogány for

[Images: Illustrations by Willy Pogány for  [Images: Illustrations by Willy Pogány for

[Images: Illustrations by Willy Pogány for  [Images: Illustrations by Willy Pogány for

[Images: Illustrations by Willy Pogány for  [Images: Illustrations by Willy Pogány for

[Images: Illustrations by Willy Pogány for  [Images: Illustrations by Willy Pogány for

[Images: Illustrations by Willy Pogány for  [Images: Illustrations by Willy Pogány for

[Images: Illustrations by Willy Pogány for  [Images: Illustrations by Willy Pogány for

[Images: Illustrations by Willy Pogány for  [Images: Illustrations by Willy Pogány for

[Images: Illustrations by Willy Pogány for  [Images: Illustrations by Willy Pogány for

[Images: Illustrations by Willy Pogány for  1) The discussion series Humans, Robots and War continues at 4pm this afternoon with “

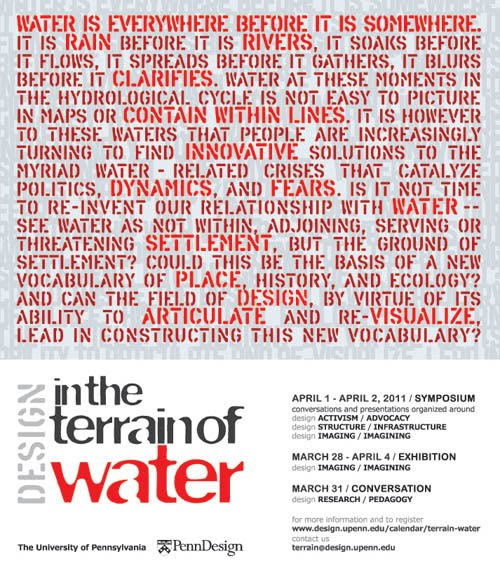

1) The discussion series Humans, Robots and War continues at 4pm this afternoon with “ 6) Speaking of water, meanwhile, on April 1-2, 2011, the University of Pennsylvania will be hosting a symposium called In the Terrain of Water: “Water is everywhere before it is somewhere. It is rain before it is rivers, it soaks before it flows, it spreads before it gathers, it blurs before it clarifies. Water at these moments in the hydrological cycle is not easy to picture in maps or contain within lines. It is however to these waters that people are increasingly turning to find innovative solutions to the myriad water-related crises that catalyze politics, dynamics, and fears. Is it not time to re-invent our relationship with water—see water as not within, adjoining, serving or threatening settlement, but the ground of settlement? Could this be the basis of a new vocabulary of place, history, and ecology? And can the field of design, by virtue of its ability to articulate and re-visualize, lead in constructing this new vocabulary?” Check out their site for

6) Speaking of water, meanwhile, on April 1-2, 2011, the University of Pennsylvania will be hosting a symposium called In the Terrain of Water: “Water is everywhere before it is somewhere. It is rain before it is rivers, it soaks before it flows, it spreads before it gathers, it blurs before it clarifies. Water at these moments in the hydrological cycle is not easy to picture in maps or contain within lines. It is however to these waters that people are increasingly turning to find innovative solutions to the myriad water-related crises that catalyze politics, dynamics, and fears. Is it not time to re-invent our relationship with water—see water as not within, adjoining, serving or threatening settlement, but the ground of settlement? Could this be the basis of a new vocabulary of place, history, and ecology? And can the field of design, by virtue of its ability to articulate and re-visualize, lead in constructing this new vocabulary?” Check out their site for