If everyone who used buildings were to form a union, how might they go on strike? They could demand faster escalators, better lobbies, wider halls – and they could boycott the buildings they work in. After all, if everyone got together and declared themselves the Building Users Union – We are the users of buildings, they say, and here is our list of demands – how might the built environment be forced to change? In other words, if architects can unionize – a big if – then why not the people who use their buildings?

Can an audience go on strike?

The users of buildings march on Washington – on Whitehall, on the UN – demanding action, and the strike goes on for years. People are soon camping in the streets, sleeping in makeshift tent cities, and refusing to enter architecture until their demands are met. The world of interiors is lost to them. Children are born in parks; schools are founded beside undammed rivers; religious services take place in wooded groves.

Architects are beside themselves. They live alone inside distant high-rises, opening windows here and there, wondering where everyone has gone.

Zoology

[Image: The future Zoo de Vincennes by TN PLUS Landscape Architects, with additional architecture by Beckmann N’Thepe].

[Image: The future Zoo de Vincennes by TN PLUS Landscape Architects, with additional architecture by Beckmann N’Thepe].

A few months ago we took a look at plans for a new zoo in Vincennes, France, being developed by landscape architects TN PLUS. I’ve since been in touch with the firm, who have sent in more images of the proposed landscape. I thought I’d post them here, then, even as I also refer everyone back to the earlier post.

[Image: The Zoo de Vincennes by TN PLUS Landscape Architects].

[Image: The Zoo de Vincennes by TN PLUS Landscape Architects].

I have to register my fascination again, however, with the idea that zoos actually represent a kind of spatial hieroglyphics through which humans communicate – or, more accurately, miscommunicate �– with other species.

That is, zoos are decoy environments that refer to absent landscapes elsewhere. If this act of reference is read, or interpreted correctly, by the non-human species for whom the landscape has been constructed, then you have a successful zoo. One could perhaps even argue here that there is a grammar – even a deep structure – to the landscape architecture of zoos.

Zoos, in this way of thinking, are at least partially subject to a rhetorical analysis: do they express what they are intended to communicate – and how has this meaning been produced?

Landscape architecture becomes an act not just of stylized geography, or aesthetically shaped terrain, but of communication across species lines.

[Images: The Zoo de Vincennes by TN PLUS Landscape Architects].

[Images: The Zoo de Vincennes by TN PLUS Landscape Architects].

Of course, this can also be inverted: are these landscapes really meant to be read, understood, and interpreted by what we broadly refer to as “animals,” or are these landscapes simply projections of our own inner fantasies of the wild? Or should I say The Wild?

While this latter scenario sounds much more likely to be the case – humans, like a broken cinema, always live inside their own projections – nonetheless, the non-human communicational possibilities of landscape architecture will continue to fascinate me.

[Image: The Zoo de Vincennes by TN PLUS Landscape Architects].

[Image: The Zoo de Vincennes by TN PLUS Landscape Architects].

In fact, briefly, I’m reminded of two things:

1) Fritz Haeg’s Animal Estates initiative, in which small homes for animals are constructed to house the native, pre-human population of urban landscapes around the world. Haeg explains that he “creates dwellings for animals,” and that these “prototype Animal Estates will be established in a variety of environments. (…) Each will be designed to attract and welcome a particular animal back into an environment that has been dominated by humans. The design for each estate will be developed with a local specialist on that particular animal.”

2) Temple Grandin, who could perhaps be described as an autistic animal theorist. Grandin has been campaigning for the re-design of slaughterhouse environments in order that they be less terrifying for animals; but what’s particularly interesting about her campaign is that – if I’ve understood this correctly – she has extrapolated from her own subjective experiences of autism in order to model how animals might experience slaughterhouse architecture. Human autism here becomes strangely elided with animal subjectivity. Grandin has thus developed an entire phenomenological architecture that takes advantage of natural animal behaviors – circling, herding, grouping, and so on – by spatializing these behaviors into the built environment. Animal movements trace out spatial parameters that the architecture itself later takes. The animals are thus doing what they would have been doing “naturally” as they enter the spinning blades…

In any case, I don’t at all mean to imply that zoos and slaughterhouses are somehow identical environments; I do mean to imply, however, that each environment, seen as a particular type of landscape, has been spatially organized around animal subjectivity and, more importantly – and, for me, substantially more interesting – around non-verbal communication with other species.

To put even more of an academic spin on this, zoos are speech acts.

[Image: The Zoo de Vincennes by TN PLUS Landscape Architects].

[Image: The Zoo de Vincennes by TN PLUS Landscape Architects].

But I’ve said much the same before; check out the earlier post for more.

Cinema City

[Image: From London After the Rain].

[Image: From London After the Rain].

onedotzero is hosting a film event this Saturday in London, promising “futuristic visions of London” and “surreal urban worlds.” Screenings will include Ben Marzys’s short film London After the Rain, produced for Nic Clear’s Unit 15 at The Bartlett, previously mentioned here.

The event costs £8.60, and things kick off around 8:45pm at Southbank.

Chinese Air Bars

In a short post on MadRegale, Wired correspondent Alexis Madrigal suggests that we should open a series of “Chinese air bars” so that people around the world can temporarily experience what it’s like to breathe the polluted city air of China.

[Image: The “air” in Beijing on June 20, 2008, with the summer Olympics less than two months away. Photo by James Fallows].

[Image: The “air” in Beijing on June 20, 2008, with the summer Olympics less than two months away. Photo by James Fallows].

China, home to some of the most polluted cities in the world, could thus capitalize on its newest export: vials of urban atmosphere. They’ll simply export the sky.

They do it already, in any case, with huge oily clouds of industrial particulates blowing halfway around the world to land as dust on the streets of California; this way they’d just make a little money from it. Athletes training for this summer’s Olympics could order it by the tankful.

It’d be like bottled water – or like Marcel Duchamp’s Paris Air, in which a 50cc phial of Paris air was exhibited as a readymade art object.

Take something; bottle it; bring it to market.

Leading me to wonder: if Marcel Duchamp had lived in a different historical era, would he perhaps have invented bottled water?

It’d be interesting, though, to open not only a Chinese air bar, but a Haitian air bar, and a Paris air bar, and an LA air bar – a whole series of air bars – or just one huge air bar in which all of these airs are served.

You could have even air flights: with a weird plastic mask attached to your face, staring deeply into the eyes of your date, you’d breathe in a succession of the rarest airs: Guangzhou followed by Cape Town followed by Rome is a particularly strong sequence. It brings out certain scents.

You could even wrap these up into complex, synesthetic packages – call it Café Synesthesia, and you’d appear on the evening news. While eating skirt steak you breathe packaged air from Sacramento. When you sip your wine, the air supply switches to a light southern Italian blend. Pasta dishes go well with air from the mountains of Colombia – and, in fifty years’ time, you can read Dave Eggers’s books while breathing air from San Francisco stored in 2008. It’s vintage. Stored under ideal conditions in steel tanks.

Or listen to Mozart while inhaling air from the streets of Vienna.

It’s the rise of the boutique air industry.

Cultural air archaeology.

Air harvesters – the preferred summer job for backpackers in 2050AD – are sent out to capture the sky in vast balloons. Air farms. The balloons are then kept in quarantine at international airports where stunned customs workers, earning minimum wage, look up at bulbous forms swaying inside hangars in semi-darkness.

The balloons are labeled: Singapore, Marrakech, São Paulo.

Next week your friends come round for a fish dinner – but it’s not complete till you seal off the room, twist a valve in the corner… and the air of central Tokyo wafts silently around you.

You’ve never eaten anything so good in your life.

Air rooms. Café Breathe.

Either way, Chinese air bars are just the start.

Agent of Change

Geoff Shearcroft, of The Agents of Change, will be coming round tomorrow at 11:30am to speak at the Storefront for Art and Architecture’s Pop Up branch here in London.

I first found Shearcroft’s work – and, thus, The Agents of Change – through a book called Fantasy Architecture: 1500-2036. There, Shearcroft’s image of a mouse with a suburban house growing out of its back – as if grafted there, or perhaps cloned – was a tongue in cheek glimpse of what Shearcroft called, in a 2001 paper for the Royal College of Art, “the new biology of architecture.”

[Image: “Grow Your Own” by Geoff Shearcroft].

[Image: “Grow Your Own” by Geoff Shearcroft].

The Agents of Change themselves have a huge array of noteworthy projects – including Monsanto New Garden City, in which it was asked: what would happen if global agri-business giant Monsanto were to purchase the London borough of Hackney…? What if they then turned it into an Agricultural Action Zone (AAZ)?

“Costly infrastructural components are replaced with a self-sufficient ecology of grass roads, localised rainwater collection, organic solar films and biological compost systems,” the architects suggest. The economically depressed borough would present “new growing opportunities,” thus “liberating the ground’s agricultural potential.”

There’s also a project known as Roof Divercity in which all the roofs of Croydon are activated as new social, economic, and agricultural spaces for the borough’s residents.

[Images: Roof Divercity by The Agents of Change].

[Images: Roof Divercity by The Agents of Change].

Meanwhile, the AOC’s recent proposal for the Birnbeck Island competition is also fantastic, involving a very colorful village and a sort of artificially amplified mountain form on a pier in the west of England.

It’s geology meets housing, offshore.

[Images: From the Birnbeck Island and Birnbeck Village proposals by The Agents of Change].

[Images: From the Birnbeck Island and Birnbeck Village proposals by The Agents of Change].

More germane to this year’s London Festival of Architecture, The Agents of Change also designed The Lift, a temporary pavilion which they describe as “a new Parliament.”

[Image: The Lift by The Agents of Change].

[Image: The Lift by The Agents of Change].

In any case, I could go on and on, uploading images of their work all day.

Shearcroft will be speaking at the Pop Up Storefront tomorrow at 11:30am – so come by to hear what he has to say.

Trainspotting

Another interviewee at tomorrow’s event is Simon Bradley, editor of the Pevsner Architectural Guides and author of St Pancras, one of the titles in Mary Beard’s ongoing Wonders of the World series.

[Image: Simon Bradley and St Pancras].

[Image: Simon Bradley and St Pancras].

The book is fantastically interesting, even for an American reader, like myself, who doesn’t have regular contact with the structure; the building, it turns out, is full of built-in eccentricities, and its existence as part of a much larger Victorian rail network is significant of remarkable social – and even dietary – changes elsewhere.

The internal spacing of the train shed, for instance, is based around a rather unique structural module: the dimensions of a barrel of Bass Ale. Bradley explains that William Henry Barlow, the 19th-century consulting engineer for Midland Railway,

dispensed with the normal mid-Victorian structural system of brick piers and arches in favour of even ranks of some eight hundred uniform cast-iron columns. These supported a grid of two thousand wrought-iron girders, which in turn underlay the iron plates on which the tracks and platforms rested. The spacing of the columns at centres just over 14 feet apart was calculated to match the plans of the beer warehouses of Burton-upon-Trent, where the same figure derived from a multiple of the standard local cask. And so, in Barlow’s words, ‘the length of a beer barrel became the unit of measure upon which all the arrangements of this floor were based’.

This, in turn, has structural implications at other points within St. Pancras, ramifying these Burtonian measurements throughout the station’s archways.

There are loads of other points to bring up here but I’ll have to resist, as 1) I’m working on a larger article about St. Pancras in which these other points will be explored, and 2) I’ll be speaking to Bradley tomorrow live at the Storefront for Art and Architecture in South Kensington, in a joint interview with Mary Beard, editor of the Wonders of the World series, at 10am.

Time Control

Tomorrow at 2pm I’ll be interviewing novelist Tom McCarthy at the Storefront for Art and Architecture here in London. McCarthy’s excellent book Remainder – which just last month won the fourth annual Believer Book Award – is about a man in London who is hit on the head by “something falling from the sky.”

He thus goes into a coma; he is involved in a lawsuit upon waking; he’s awarded £8.5 million in damages. This all takes place in the first few pages.

[Image: Tom McCarthy and Remainder].

[Image: Tom McCarthy and Remainder].

The rest of the book is about the narrator’s attempt to figure out what exactly to do with all that money – as well as how he can recreate, to a hilariously precise extent, a building in which he might (or might not) have once lived.

What happens is that he’s struck by a moment of déjà vu while in the bathroom at a friend’s party, and so he realizes, with a sense of overwhelming purpose bordering on religious epiphany, that he must use his new-found funds to reconstruct the exact circumstances of the moment to which that déjà vu referred. If he can’t remember everything about that déjà vu in its entirety, in other words – well, then, he’ll just physically recreate it. It’s a “forensic procedure.”

After all, he’s got £8.5 million. What else is he going to do?

To facilitate this projective act of mnemonic reconstruction, he first gets in touch with real estate agents. In Chapter 5 – a chapter which should be required material in certain architectural design courses – we read:

I spoke to three different estate agents. The first two didn’t understand what I was saying. They offered to show me flats – really nice flats, ones in converted warehouses beside the Thames, with open plans and mezzanines and spiral staircases and balconies and loading doors and old crane arms and other such unusual features.

“It’s not unusual features that I’m after,” I tried to explain. “It’s particular ones. I want a certain pattern on the staircase – a black pattern on white marble or imitation marble. And I need there to be a courtyard.”

“We can certainly try to accommodate these preferences,” this one said.

“These are not preferences,” I replied. “These are absolute requirements. (…) And it’s not one property I’m after,” I informed her. “It’s the whole lot. There must be certain neighbors, like this old woman who lives below me, and a pianist two floors below her, and…”

Getting nowhere with the agents of already-existing London real estate, he turns to the services of a firm called Time Control. Time Control can make things happen – very precise things.

He soon meets up with Nazrul Ram Vyas, a representative of the firm.

“I have a large project in mind,” I said, “and wanted to enlist your help.” “Enlist” was good. I felt pleased with myself.

“Okay,” said Naz. “What type of project?”

“I want to buy a building, a particular type of building, and decorate and furnish it in a particular way. I have precise requirements, right down to the smallest detail. I want to hire people to live in it, and perform tasks that I will designate. They need to perform these exactly as I say, and when I ask them to. I shall most probably require the building opposite as well, and most probably need it to be modified. Certain actions must take place at that location too, exactly as and when I shall require them to take place. I need the project to be set up, staffed and coordinated, and I’d like to start as soon as possible.”

“Excellent,” Naz said, straight off. He didn’t miss a single beat. I felt a surge inside my chest, a tingling.

They later discuss what some of these hired residents will do.

“What tasks would you like them to perform?”

“There’ll be an old woman downstairs, immediately below me,” I said. “Her main duty will be to cook liver. Constantly. Her kitchen must face outwards to the courtyard, the back courtyard onto which my own kitchen and bathroom will face too. The smell of liver must waft upwards. She’ll also be required to deposit a bin bag outside her door as I descend the staircase, and to exchange certain words with me which I’ll work out and assign to her.”

“Understood,” said Naz. “Who’s next?”

In any case, to make a long story short, the narrator goes on to audition actors – or re-enactors – and to become increasingly unhinged. Weird chains of events extending well outside the original architectural structure are acted out – including a robbery – and re-enactors are soon hired to re-enact earlier actions by the first group of re-enactors. The whole thing takes on the feel of a nomadic and vaguely schizophrenic opera troupe on the loose in Greater London, performing scenes from a life that never really happened, under the illusion that they’re helping an eccentric millionaire to get his lost memories back.

Three quick questions, then:

1) On the most basic level, how different are some of the narrator’s requests from the precise, arcane, and well-practiced moves of 19th-century butlers and other house attendants? In other words, what appears to be mania in a person hit on the head by an unidentified piece of technology falling from the sky is seen as tradition, class structure, and ritualistic social role in the lives of others.

2) What on earth would it have been like to work for someone like the legendarily eccentric Howard Hughes, who had not £8.5 million to spend on strange projects but literally billions? Or, more interestingly, from the standpoint of a novelist, what other, far more ambitious demands could Hughes have made of his staff? I’m tempted to pitch a novella in which Howard Hughes has sent a small team of actors deep into the Andes where they are required to build a house just like his own, to change their names to Howard for exactly one year, and to act out forgotten moments from his own past on a precisely worked out schedule. There are bells, alarms, and inspections. Until one of them gets fed up…

3) There was an interesting article in The New Yorker several months ago about the use of immersive, 3D simulations of war scenes from Iraq to help treat post-traumatic stress disorder in returning soldiers. The general idea was that, by confronting, over and over again, the very thing that once traumatized you, you could nullify its long-term psychological effects. But what if these immersive simulations didn’t have to take place on computer screens inside military labs? Perhaps a returning soldier – the son of a refrigeration billionaire – will take matters into his own hands on a large estate in South Dakota, building vast stage sets… Remainder 2: Return to Basra.

So I’ll be speaking with Tom McCarthy tomorrow, July 4th, at 2pm, in South Kensington. Feel free to stop by!

BLDGBLOG’s 4th of July Live Interview Marathon in London

I’m in London – in fact, I’m sitting at a table in the basement of the Building Centre – with some great things lined up for the week. One event, in particular, though, seems worthy of mention here.

This Friday, on the 4th of July, I will be moderating an all-day series of live interviews hosted at the Storefront for Art and Architecture’s Pop Up London venue in the Exhibition Road, South Kensington, as part of the London Festival of Architecture.

[Image: The Storefront for Art and Architecture’s Pop Up space in London].

[Image: The Storefront for Art and Architecture’s Pop Up space in London].

Surrounded by architectural models installed by the Bjarke Ingels Group, I will be in back-to-back conversations with:

10am: Mary Beard, Professor of Classics at Cambridge University and author of The Parthenon and The Roman Triumph, among many others, and Simon Bradley, Editor of the Pevsner Architectural Guides and author of St. Pancras

11:30am: Architect Geoff Shearcroft of the Agents of Change

2pm: Novelist Tom McCarthy, author of Remainder and Men in Space

3pm: Landscape architects Mark Smout and Laura Allen of Smout Allen, authors of Augmented Landscapes

4pm: Architect and theorist Alex Haw of atmos

5pm: Architectural gentlemen Sam Jacob, Sean Griffiths, and Charles Holland of FAT

I’m unbelievably excited about this, in fact, not least because I will finally be meeting in person so many people with whom I’ve long been in email contact – but also because I can hardly think of a better list of people with whom I’d rather spend the day here in London.

The interviews are live, free, and open to the public – but bear in mind that the space is quite small, and BIG‘s models are, yes, quite big, and so there will be very little room for a comfortable audience. We’re thus downplaying the live nature of these discussions, but we are videotaping all of them for later posting on the Storefront’s website. I also hope that these will be transcribed for later publication. I really can’t wait, actually.

So if you are in London, please feel free to stop by and introduce yourself, whether you’re a reader of BLDGBLOG or not. You’ll be able to ask your own questions of the interviewees – and, who knows, maybe even get them to autograph a book or two.

And I hope to be posting at an acceptable pace this week, as well.

Finally, here is a map.

Martian Garden

[Image: Courtesy of NASA/JPL-Caltech/University of Arizona].

[Image: Courtesy of NASA/JPL-Caltech/University of Arizona].

The soil chemistry on Mars is apparently just right for growing turnips. After digging up soil in a region of the Red Planet nicknamed Wonderland, the Phoenix rover “found trace levels of nutrients like magnesium, sodium, potassium and chloride,” which is “the same basic chemistry as garden soil.” These soil samples are also “fairly alkaline,” we read, “with a pH of 8 or 9. This level of alkalinity is common for many Earth soils, and myriad bacteria and plants, including vegetables like asparagus and turnips, can thrive at such a pH.”

So could we develop Mars gardens in our landscape architecture classes – pre-emptive landscape grafts that we’ll export off-world for future planting?

London is swimming

[Image: Photo by Gigi Cifali; view larger].

[Image: Photo by Gigi Cifali; view larger].

There was an interesting overlap the other week between Time Out London‘s cover story, “Swim City,” about London’s “best pools, ponds and lidos,” and Polar Inertia‘s newest issue featuring beautiful photographs of abandoned swimming pools throughout the greater London area.

[Image: Photo by Gigi Cifali; view larger].

[Image: Photo by Gigi Cifali; view larger].

“Great pools?” Time Out asked. “From marble-clad baths dripping in history to modern leisure centres echoing with lifeguards’ whistles, London is swimming in them.”

Except, of course, many of its pools are also drained and forgotten.

[Image: Photo by Gigi Cifali; view larger].

[Image: Photo by Gigi Cifali; view larger].

The photos here are all by Gigi Cifali, who originally trained as a topographer, from a series called “Absence of Water.” The images document the disused pools of London – and there are many more of these photos to be seen over at Polar Inertia or on Cifali’s own website.

[Images: Photos by Gigi Cifali; view larger: top and bottom].

[Images: Photos by Gigi Cifali; view larger: top and bottom].

I’m reminded, though, of a great line from J.G. Ballard’s novel Empire of the Sun:

Jim watched Mr. Maxted sway along the tiled verge of the empty swimming pool, curious to see if he would fall in. If Mr. Maxted was always accidentally falling into swimming pools, as indeed he always was, why did he only fall into them when they were filled with water?

Why, indeed.

(All photos by Gigi Cifali).

For whom the bell tolls

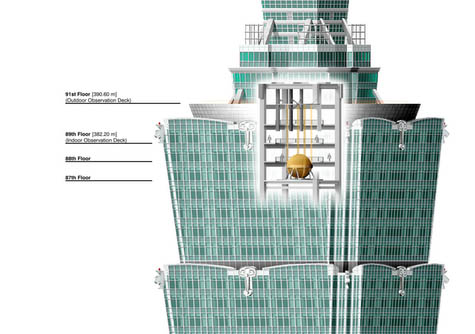

[Image: Diagram of Taipei 101’s earthquake ball via the Long Now Foundation].

[Image: Diagram of Taipei 101’s earthquake ball via the Long Now Foundation].

Earlier this week, the Long Now Foundation looked at earthquake dampers inside skyscrapers, focusing specifically on Taipei 101—a building whose unanticipated seismic side-effects (the building’s construction might have reopened an ancient tectonic fault) are quite close to my heart.

As it happens, Taipei 101 includes a 728-ton sphere locked in a net of thick steel cables hung way up toward the top of the building. This secret Piranesian moment of inner geometry effectively acts as a pendulum or counterweight—a damper—for the motions of earthquakes.

[Image: The 728-ton damper in Taipei 101, photographed by ~Wei~].

[Image: The 728-ton damper in Taipei 101, photographed by ~Wei~].

As earthquake waves pass up through the structure, the ball remains all but stationary; its inertia helps to counteract the movements of the building around it, thus “dampening” the earthquake.

It is a mobile center, loose amidst the grid that contains it.

[Image: Animated GIF via Wikipedia].

[Image: Animated GIF via Wikipedia].

However, there’s something about discovering a gigantic pendulum inside a skyscraper that makes my imagination reel. It’s as if the whole structure is a grandfather clock, or some kind of avant-garde metronome for a musical form that hasn’t been invented yet. As if, down there in the bedrock, or perhaps a few miles out at sea inside a submarine, every few seconds you hear the tolling of a massive church bell – but it’s not a bell, it’s the 728-ton spherical damper inside Taipei 101 knocking loose against its structure.

Or it’s like an alternate plot for Ghostbusters: instead of finding out that Sigourney Weaver’s New York high-rise is literally an antenna for the supernatural, they realize that it’s some strange form of architectural clock, with a massive pendulum inside—a great damper—its cables hidden behind closet walls and elevator shafts covered in dust; but, at three minutes to midnight on the final Halloween of the millennium, a deep and terrifying bell inside the building starts to toll.

The city goes dark. The tolling gets louder. In all the region’s cemeteries, the soil starts to quake.

(Thanks to Kevin Wade Shaw for the link!)