[Image: A U.S. Predator drone, photographed by Lt. Col. Leslie Pratt, courtesy of the U.S. Air Force via Wikipedia].

[Image: A U.S. Predator drone, photographed by Lt. Col. Leslie Pratt, courtesy of the U.S. Air Force via Wikipedia].

The Send Equipment for National Defense Act, sponsored by Texas Representative Ted Poe, would “require that 10 percent of certain equipment returned from Iraq—like Humvees, night-vision equipment and unmanned aerial surveillance craft—be made available to state and local agencies for border-security operations.”

Poe denies that this would militarize the border, as reported by the New York Times; but John Cook, mayor of the border city of El Paso, strongly disagrees, suggesting that only “a whole lot of ignorance” could inspire the plan. Cook points out that “moving war zone equipment to the border would send the wrong signal to Mexico and potentially damage the robust symbiotic economic relationship between the two countries.”

This comes at the same time that Miller-McCune warns that “armed police drones”—or weaponized UAVs—might soon be flying through a sky near you. While Miller-McCune focuses specifically on the sheriff of Montgomery County, Texas, it’s worth pointing out that so-called Leptron Avengers—”battery-operated helicopters designed to take high-resolution video and photos and that can be equipped with night-vision cameras or thermal-imaging equipment”—have also been requested by the Texas city of Arlington, perhaps making Texas—alongside such places as Syria, North Korea, and China—the go-to site today for witnessing civilian adaptations of military surveillance technology.

[Image: The ShadowHawk unmanned police helicopter by Vanguard Defense Industries, via Miller-McCune].

[Image: The ShadowHawk unmanned police helicopter by Vanguard Defense Industries, via Miller-McCune].

The current version of this equipment, called the ShadowHawk, “won’t carry weapons,” we’re told, but “the drone’s manufacturer, Vanguard Defense Industries, boasts that it’s strong enough to carry a shotgun or even a grenade launcher.” The firm itself adds that the “ShadowHawk can maintain aerial surveillance of an area (i.e. house, vehicle, person, etc.) at 700 feet without being heard or seen unlike full sized aircraft. Imagine the advantage provided to an entry team in the following scenarios: high risk warrant, hostage rescue, domestic violence, etc.”

Mechanized urban surveillance is hardly news. Indeed, the currently existing network of CCTV cameras already installed in cities all over the world is equally “unmanned,” in an exactly comparable sense; they are fixed-point drones. One could thus make an argument that the ShadowHawk is simply a camera with wings: you have a camera outside CVS or Tesco, ergo you have a camera in the sky above the city. It’s easy to see how “mission creep,” as Miller-McCune calls it, could occur.

Or compare this, for instance, to plans aflight in the UK, where police “are planning to use unmanned spy drones, controversially deployed in Afghanistan, for the ‘routine’ monitoring of antisocial motorists, protesters, agricultural thieves and fly-tippers, in a significant expansion of covert state surveillance.” This will take the form of unmanned airships hovering over the English capital, as if simulating the barrage balloons of World War II.

[Image: Barrage balloons above London, courtesy of Wikipedia].

[Image: Barrage balloons above London, courtesy of Wikipedia].

The drones “are programmed to take off and land on their own, stay airborne for up to 15 hours and reach heights of 20,000ft, making them invisible from the ground,” and they will be launched “in time for the 2012 Olympics.” (An Afghanistan-based version of this program is described as follows: “This fall, there’ll be a new supercomputer in Afghanistan. It’ll be floating 20,000 feet above the warzone, aboard a giant spy blimp that watches and listens to everything for miles around.”)

[Images: From an October 2009 presentation by Major General Blair Hansen to the U.S. Strategic Command and Defense Intelligence Agency].

[Images: From an October 2009 presentation by Major General Blair Hansen to the U.S. Strategic Command and Defense Intelligence Agency].

Briefly, I’m reminded of the opening scene from Christopher Dickey’s book Securing the City, in which a helicopter that falls somewhere between aerial war machine and advanced Hollywood film equipment is breathlessly unveiled: “The winter air is cold and the light hard-edged as the unmarked New York City Police Department helicopter meanders through the winds above the five boroughs,” we read.

It is a state-of-the-art crime-fighting, terror-busting, order-keeping techno toy, with its enormous lens that can magnify any scene on the streets almost one thousand times, then double that digitally; that can watch a crime in progress from miles away, can look in windows, can sense the body heat of people on rooftops or running along sidewalks, can track beepers slipped under cars, can do so very many things that the man in the helmet watching the screens and moving the images with the joystick in his lap, NYPD Detective David Zschau, is often a little bit at a loss for words. “It really is an amazing tool,” he keeps saying.

This technology—whose unlimited vision seems so mind-boggling as to cause aphasia in those who encounter it—should inspire as much moral and political discomfort as an unmanned version of the same helicopter; in other words, we shouldn’t lose sight of the fact that this very kind of spy equipment already exists and has already been deployed. That is, the unnerving implication that we are being watched from above by undetectable robots should not let us forget that being watched from above by human pilots is just as invasive.

In any case, the ShadowHawk, described above, can also be put to use in fire and rescue situations, able to track down “heat sources and cut through the smoke and haze with it’s Forward Looking Infrared (FLIR) or SWIR”—short wave infrared—cameras. Indeed, the company points out that “the vast capabilities of the ShadowHawk are ideal for mitigating and handling disasters whether natural or manmade. From locating victims, serving as an airborne communications relay point or conducting damage assessment, the ShadowHawk will significantly expand response capabilities.” In light of this, it is foolish to reject, universally and in principle, the very idea of unmanned systems operating in non-military environments; but it’s equally foolish to welcome them without a simultaneous demand for strong regulation and oversight.

To be honest, though, it seems only a matter of time before armed police drones are a reality in the United States, and it would thus be great to see a long discussion of the legality—or, at the very least, the societal implications—of such equipment, before we are faced with a scenario none of us adequately understand. For instance, is there a law course somewhere examining the rights and implications of autonomous urban police technologies? Combine this with a look at repurposed military hardware used in patrolling national borders, and the syllabus from such a course would be well worth exploring in detail.

(In addition to the London example, cited above, another rebuke to the moral self-congratulation of the Miller-McCune piece comes from Northern Ireland, where the use of unmanned aerial systems in urban policing might soon take the form of “mini drones” used “to combat crime and the dissident republican threat”—in other words, autonomous police drones are by no means limited to cities in the United States).

[Image: Window by Susanna Battin, courtesy of the artist].

[Image: Window by Susanna Battin, courtesy of the artist].

[Images: From

[Images: From

[Images: From

[Images: From

[Images: From

[Images: From

[Images: From

[Images: From

[Images: From

[Images: From

[Image: From “

[Image: From “ [Image: From “

[Image: From “

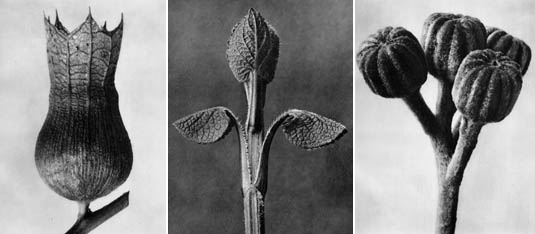

[Images: Botanical photogravures by

[Images: Botanical photogravures by  [Images: More extraordinary photogravures by

[Images: More extraordinary photogravures by  [Image:

[Image:

[Image: A U.S. Predator drone, photographed by Lt. Col. Leslie Pratt, courtesy of the U.S. Air Force via

[Image: A U.S. Predator drone, photographed by Lt. Col. Leslie Pratt, courtesy of the U.S. Air Force via  [Image: The

[Image: The  [Image: Barrage balloons above London, courtesy of

[Image: Barrage balloons above London, courtesy of

[Images: From an October 2009 presentation by Major General Blair Hansen to the

[Images: From an October 2009 presentation by Major General Blair Hansen to the

[Image: Men of Good Fortune, North Kivu, Eastern Congo, by

[Image: Men of Good Fortune, North Kivu, Eastern Congo, by  [Image: Lava Floe, North Kivu, Eastern Congo, by

[Image: Lava Floe, North Kivu, Eastern Congo, by

[Images: (top to bottom) Flower of the Mountain, House Of Cards V, and Come Out (1966) II, all by

[Images: (top to bottom) Flower of the Mountain, House Of Cards V, and Come Out (1966) II, all by

[Images: (top) Nowhere To Run, South Kivu, Eastern Congo (2010); (bottom) Taking Tiger Mountain, North Kivu, Eastern Congo (2011), by

[Images: (top) Nowhere To Run, South Kivu, Eastern Congo (2010); (bottom) Taking Tiger Mountain, North Kivu, Eastern Congo (2011), by  [Image: Blue Mask, Lake Kivu, Eastern Congo (2010) by

[Image: Blue Mask, Lake Kivu, Eastern Congo (2010) by

[Image: Photo by

[Image: Photo by

[Image: “L.A. Ice” by Victor Hadjikyriacou, produced for Unit 11 at the Bartlett School of Architecture, part of last year’s

[Image: “L.A. Ice” by Victor Hadjikyriacou, produced for Unit 11 at the Bartlett School of Architecture, part of last year’s  [Image: “A water truck passes over the ice road spreading a thin layer of water to thicken the ice so it can support heavy equipment transport”; photo courtesy of the

[Image: “A water truck passes over the ice road spreading a thin layer of water to thicken the ice so it can support heavy equipment transport”; photo courtesy of the  [Image: “Soldiers from the 6th Engineer Battalion, Fort Richardson, Alaska, clear water lines during construction of an ice bridge at the U.S. Army Cold Regions Test Center at Fort Greely, Alaska, Jan. 12, 2011.” Photo by

[Image: “Soldiers from the 6th Engineer Battalion, Fort Richardson, Alaska, clear water lines during construction of an ice bridge at the U.S. Army Cold Regions Test Center at Fort Greely, Alaska, Jan. 12, 2011.” Photo by

[Image: Liam Young flying self-illuminated drone quadcopters in Holland for a celebratory nighttime crowd].

[Image: Liam Young flying self-illuminated drone quadcopters in Holland for a celebratory nighttime crowd].

[Image: Via

[Image: Via  [Image: Via

[Image: Via  [Image: An artificial meteorology hovers over China; via

[Image: An artificial meteorology hovers over China; via