[Image: “Crane Rooms and Keg Apartments” by Aristide Antonas].

[Image: “Crane Rooms and Keg Apartments” by Aristide Antonas].

Architect Aristide Antonas will be speaking tonight, Tuesday, June 8, at the Bauhaus–Universität in Weimar, Germany. Antonas’s Flickr set has long been a favorite of mine, as it thoroughly documents his work, which radically reuses existing structures and pieces of mobile industrial equipment, such as cranes, trucks, and buses. In fact, you might recognize his “Crane Rooms” project from ArchDaily.

His “Bus Hotel,” for instance, is a double-decker bus transformed into a mobile, 7-bed hotel.

[Images: “Bus Hotel” by Aristide Antonas].

[Images: “Bus Hotel” by Aristide Antonas].

The “Keg Apartment,” designed in collaboration with Katerina Koutsogianni, continues what Antonas calls his “stable vehicle” series. There, “existing transportation wagons of different types… form rooms that can still move or can function again as movable. They can be used as holiday rooms or as small office places.”

[Images: “Keg Apartment” by Aristide Antonas and Katerina Koutsogianni].

[Images: “Keg Apartment” by Aristide Antonas and Katerina Koutsogianni].

His “Crane Rooms,” mentioned earlier, deserve a look here—

[Images: “Crane Rooms” by Aristide Antonas and Katerina Koutsogianni].

[Images: “Crane Rooms” by Aristide Antonas and Katerina Koutsogianni].

—about which Antonas writes:

Simple concrete foundations and elementary water pools are proposed to be installed in non hospitable beaches or arid hills nearby the sea. The room units form independent cells, they can be covered by tissues during the day; they provide a quality connection to the Internet. The private or public character of each room is regulated by the chosen high of every unit. The high control system is located inside every room. Platforms go up and down following the will of every provisional inhabitant. A bigger screen, related to the bed, serves as a home cinema structure; a small office, a wardrobe and a shower are placed in the same moving platform. A common underground kitchen serves the needs of all the complex; a reverse osmosis desalination plant provides drinkable water to the invisible kitchen and to the units (the water pipes follow the length of the crane).

He also proposes the construction of a “Crane Room Hotel” in which a network of individual units “moving up and down provide summer shelters with changing views.”

[Images: “Screen Wall House” by Aristide Antonas, including a map of possible sites and locations].

[Images: “Screen Wall House” by Aristide Antonas, including a map of possible sites and locations].

I’m more or less just randomly sampling his Flickr page, but “Screen Wall House” also deserves a quick look. Here, from what I can gather, a roofless island camping structure has the ability to expand indefinitely with the addition of further walls. “The walls that form this house are made out of screens,” Antonas writes. “These thin walls arrive by boat and are maintained by the desert place company, which is something similar to a camping set with particular rules. The screens can be added to existing concrete bases. A power engine provides the electricity that is needed for each unit.” The architecture, then, is dependent on the concrete floor plan laid out in advance by the “desert place company”—but one can easily imagine an alternative wall-structure that brings its modular floor plates along with it, thus allowing these flexi-mazes of temporary screens to encompass unprecedented interior spaces without a need for prior planning.

In any case, Antonas will be presenting his work at the Bauhaus-Universität in only a matter of hours; say hello to him if you happen to be there tonight.

[Image: “

[Image: “ [Image: “

[Image: “ [Image: “

[Image: “ [Image: “Stonehenge at Night” (1944) by Harold Edgerton].

[Image: “Stonehenge at Night” (1944) by Harold Edgerton].

[Image: “A 1566 rendering of ‘terrible and curious’ quake damage” in Istanbul; courtesy of the

[Image: “A 1566 rendering of ‘terrible and curious’ quake damage” in Istanbul; courtesy of the

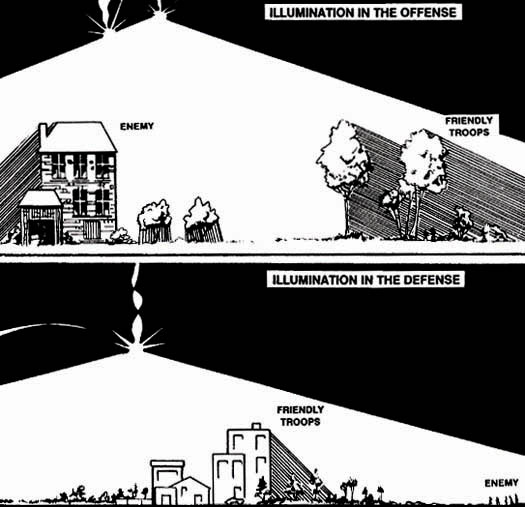

[Image: “Trip flares, flares, illumination from mortars and artillery, and spotlights (visible light or infrared) can be used to blind [the] enemy… or to artificially illuminate the battlefield,” from

[Image: “Trip flares, flares, illumination from mortars and artillery, and spotlights (visible light or infrared) can be used to blind [the] enemy… or to artificially illuminate the battlefield,” from  [Image: The Duplicative Forest—17,000 acres of identical trees—awaits; photo courtesy of

[Image: The Duplicative Forest—17,000 acres of identical trees—awaits; photo courtesy of  [Image: Archaeologists work at

[Image: Archaeologists work at

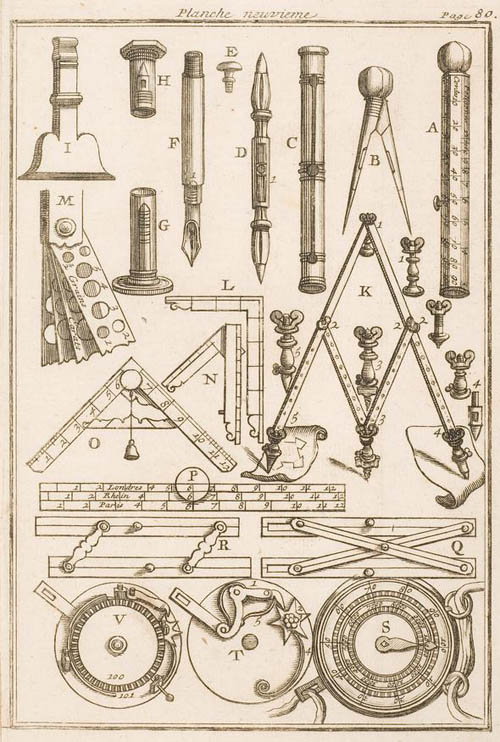

[Image: From the

[Image: From the  [Image: “Unknown photographer.

[Image: “Unknown photographer.  [Image: From

[Image: From  [Image: “

[Image: “ [Image: A

[Image: A  [Image: A

[Image: A  [Image: Photo by

[Image: Photo by  [Image: Photo by

[Image: Photo by  [Image: Photo by

[Image: Photo by  [Image: Photo by

[Image: Photo by  [Image: Photo by

[Image: Photo by  [Image: Photo by

[Image: Photo by  [Image: Photo by

[Image: Photo by  [Image: Photo by

[Image: Photo by  [Image: Photo by

[Image: Photo by  [Image: From

[Image: From  [Image: From

[Image: From

[Images: From

[Images: From  [Image:

[Image:  [Image: Berthier’s Door—near 1 Rue Chapon—visible on

[Image: Berthier’s Door—near 1 Rue Chapon—visible on