[Image: “Stonehenge at Night” (1944) by Harold Edgerton].

[Image: “Stonehenge at Night” (1944) by Harold Edgerton].

In 1944, Harold Edgerton, one of the forefathers of stroboscopic photography, produced an extraordinary image of Stonehenge. According to the authors of Stopping Time, that image was commissioned specifically as part of a larger military/optical experiment:

Illuminated by a 50,000 watt-second flash in the bay of a night-flying airplane 1500 feet above the ancient monoliths, Edgerton’s pictures of Stonehenge served as a demonstration to the Allied commanders of the potential for nighttime reconaissance photography. Edgerton was on the ground with a folding pocket camera braced on a fence post as the plane flew overhead. Simultaneously, the monument was recorded in perfect detail by a camera in the plane. The target was chosen because it was remote enough to allow the equipment to be tested without arousing unwanted interest.

Edgerton’s photograph was pointed out to me recently by architect Nat Chard after he read an earlier post here about the illuminative possibilities of aerial weaponry—or military chiaroscuro.

But the idea of a stroboscopic light-bay opening up in the base of an aircraft and illuminating scenes of human prehistory from above is breathtaking—as if dropping illuminative ordnance into a world of darkness, far below. Indeed, as a photographic technique, pinpoint-flashes of high-powered aerial lighting would also be something well worth exploring in other archaeo-architectural contexts, from Angkor Wat to the Spiro Mounds. Light-bomb archaeology.

(Thanks, Nat!)

[Image: “A 1566 rendering of ‘terrible and curious’ quake damage” in Istanbul; courtesy of the

[Image: “A 1566 rendering of ‘terrible and curious’ quake damage” in Istanbul; courtesy of the

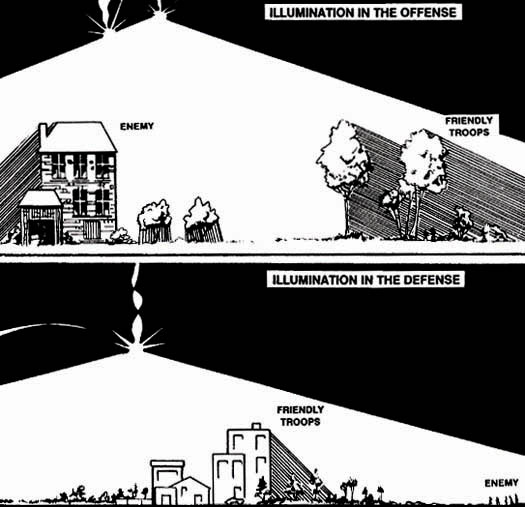

[Image: “Trip flares, flares, illumination from mortars and artillery, and spotlights (visible light or infrared) can be used to blind [the] enemy… or to artificially illuminate the battlefield,” from

[Image: “Trip flares, flares, illumination from mortars and artillery, and spotlights (visible light or infrared) can be used to blind [the] enemy… or to artificially illuminate the battlefield,” from  [Image: The Duplicative Forest—17,000 acres of identical trees—awaits; photo courtesy of

[Image: The Duplicative Forest—17,000 acres of identical trees—awaits; photo courtesy of  [Image: Archaeologists work at

[Image: Archaeologists work at