[Image: The subterranean Flower Factory of Naples by Marco Zanuso; photograph by BLDGBLOG of an image from Rassegna].

[Image: The subterranean Flower Factory of Naples by Marco Zanuso; photograph by BLDGBLOG of an image from Rassegna].

I thought I’d kick off a series of posts looking at my time spent so far going through the “Underground Space Center Library” archives at the Canadian Centre for Architecture with a look at a summer 2007 issue of Rassegna magazine, its topic nothing other than underground architecture or architetture sotteranee. While the issue is not actually part of the “Underground Space Center Library” archives, it makes a convenient starting part for a few new posts.

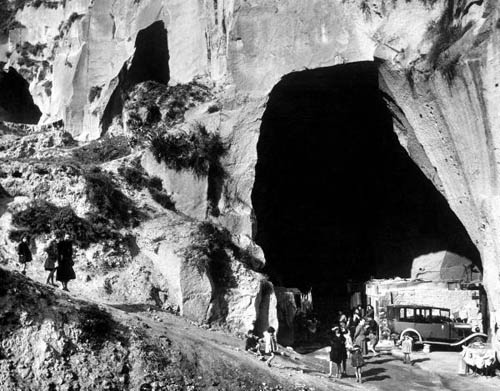

The city of Naples, as many readers will know, is built atop a series of caverns. These continue throughout the coastal region, extending down the coast for quite some time to form grottoes, harbors, and coves; they have been depicted throughout art history and used for everything from smuggling illicit goods (see Roberto Saviano’s Gomorrah, for instance) to sheltering the populace from bombing raids during World War II.

[Images: Joseph Wright of Derby, Cavern, near Naples (1774) and A Grotto in the Gulf of Salerno, Sunset (1780-81)].

[Images: Joseph Wright of Derby, Cavern, near Naples (1774) and A Grotto in the Gulf of Salerno, Sunset (1780-81)].

As the BBC reported a few years back, these caves “have been dug out over thousands of years and used for everything from aqueducts to air raid shelters.” Though “more than 900 have been discovered so far,” they add, “that is believed to be only a third of what actually lies below.” Approximately 2,700 caves, then: there is a whole other world beneath greater Naples.

Photographer Margaret Bourke-White was sent by LIFE magazine to document the wartime reuse of the city’s most prominent geological features; from children playing on gravel hillsides to teetering stacks of agricultural machinery waiting quietly in the darkness for the day they could be reactivated, every conceivable activity of everyday life was hosted underground.

[Images: All photos by Margaret Bourke-White, courtesy of LIFE magazine].

[Images: All photos by Margaret Bourke-White, courtesy of LIFE magazine].

But what sorts of sustained, economically pragmatic uses for these spaces might we develop today?

In 1988, an exhibition called Sottonapoli—Beneath Naples—explored possible architectural transformations of the caves.

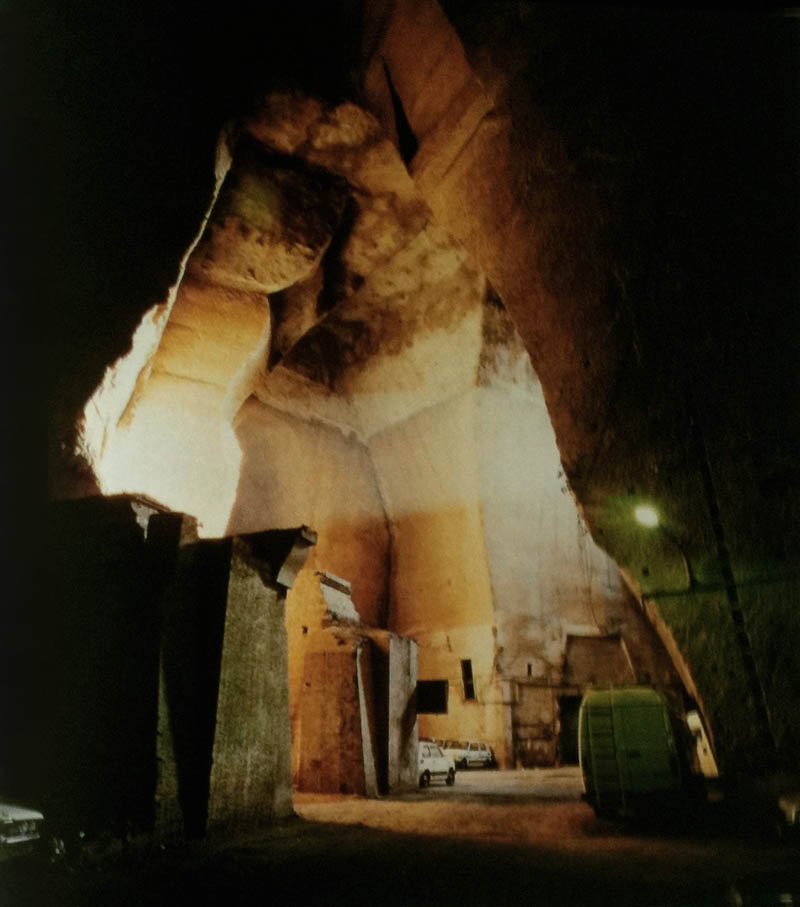

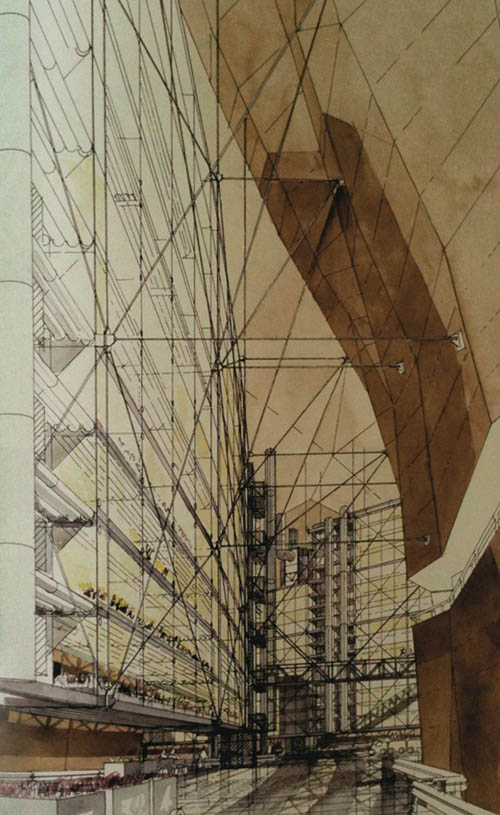

Amongst those projects was a proposal for an automated “Flower Factory” by Marco Zanuso.

[Image: Underneath Naples; photograph by BLDGBLOG of an image from Rassegna].

[Image: Underneath Naples; photograph by BLDGBLOG of an image from Rassegna].

As Francesco Trabucco, one of Zanuso’s collaborators on the project, wrote in Rassegna‘s underground issue, the project was for—and the parenthetical comments here are Trabucco’s own—”a large phytotron (a neologism referring to an accelerator of natural growth).” He continues:

The operating principle of the phytotron involves creating and monitoring the optimum microenvironment for plant growth: temperature, air humidity, lighting, photoperiodism and nutrition. At the same time, all negative factors tied to the natural environment are eliminated, i.e. climatic variation, the unpredictability of precipitation, variability in the length of the solar day, and—naturally—air and water pollution, and infestation by plants and animals. In the conditions created inside a phytotron, a plant grows at a pace that can be accelerated, with the complete absence of pollutants that are now widely present in plants grown ‘naturally,’ such as weed killers, insecticides, pesticides, acid rain, smog deposits and chemical fertilizers.

It’s basically an underground greenhouse, of course, but a fully automated one forming its own subterranean microclimate. Think of it as a buried version of VW’s legendary CarTowers in Wolfsburg, Germany, crossed with the indoor skyscraper farms so popular on architecture blogs back in 2007. The botanical results are not tomatoes, corn, wheat, or cucumbers, however, but prize flowers.

It’s a kind of pharaonic Keukenhof, or a cultivated series of entombed precision-microclimates powered by a surrogate sun.

[Image: The subterranean Flower Factory of Naples by Marco Zanuso; photograph by BLDGBLOG of an image from Rassegna].

[Image: The subterranean Flower Factory of Naples by Marco Zanuso; photograph by BLDGBLOG of an image from Rassegna].

Indeed, “A circular system of solar mirrors is designed to be installed on the ground level,” Trabucco explains, “thereby concentrating enormous amounts of thermal energy to a steam ball set on an upper level. The latter produces superheated steam to power the electric turbines.”

Nearby that is “a sterile laboratory, set up at the system entrance, in which plant cloning and micropropagation are conducted.” Successful shoots are then “placed in growth chambers until they are large enough to transplant to trays, which have holes that are sized and spaced according to the morphology of the individual plants.”

These aeroponic trays of engineered flowers are then placed, via automated relay, into a series of “maturation tunnels”—in many ways quite similar to the mushroom tunnel of Mittagong—”that are 1.8 meters wide and about 100 meters long. Tunnel height varies to cater to plant morphology; the number of overlaid tunnels or growth levels depends on the height of the gallery.”

From there, these flowers grown in such unique architectural circumstances would be harvested, pruned, crated, and shipped all over the world—and probably no one would know their actual origin.

[Image: The Flower Factory by Marco Zanuso; photograph by BLDGBLOG of an image from Rassegna].

[Image: The Flower Factory by Marco Zanuso; photograph by BLDGBLOG of an image from Rassegna].

In any case, the possible underground future of botanical cultivation, using specialty equipment and architectural design to transform caves into ornamental flower farms or large-scale plantations, is something I’ll mention again while exploring the archives of the “Underground Space Center Library” at the CCA.

(For more CCA-related posts, click here).

[Image: Diver Carlos Barrios is lowered into the sewers of Mexico City; Julio Cou Cámara can be seen on the right. Photo by Mary Jordan, courtesy of the

[Image: Diver Carlos Barrios is lowered into the sewers of Mexico City; Julio Cou Cámara can be seen on the right. Photo by Mary Jordan, courtesy of the

I think easily the most sobering thing I’ve read in a long time is that the BP Gulf oil spill

I think easily the most sobering thing I’ve read in a long time is that the BP Gulf oil spill

[Images: Multiple projects by

[Images: Multiple projects by  [Image: Service-installation by

[Image: Service-installation by  [Image: A military village by

[Image: A military village by  [Image: A military village by

[Image: A military village by

[Image: The “modular datacenter” of Sun’s

[Image: The “modular datacenter” of Sun’s  [Image: Mexico’s “Cavern of Crystal Giants” photographed by

[Image: Mexico’s “Cavern of Crystal Giants” photographed by

[Image: “Soldiers in the triumphal entry of Henri II into Rouen in 1550,” engraver unknown, from Mary Beard,

[Image: “Soldiers in the triumphal entry of Henri II into Rouen in 1550,” engraver unknown, from Mary Beard,

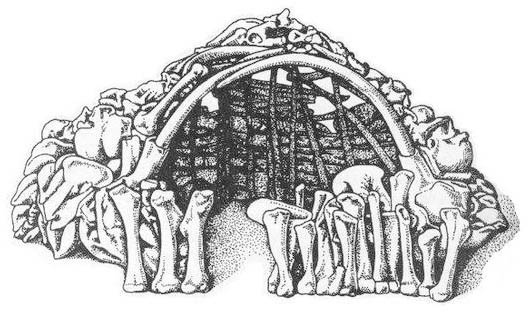

[Image: Mammoth bone hut; unknown illustrator].

[Image: Mammoth bone hut; unknown illustrator]. [Image: Alessandro Poli, Zeno-research of a self-sufficient culture (1979-80). ©Archivio Alessandro Poli. Photo: Antonio Quattrone. Courtesy of the

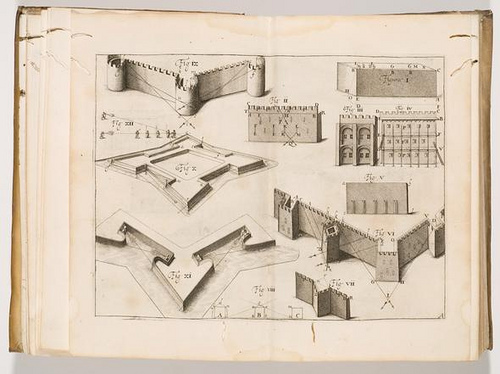

[Image: Alessandro Poli, Zeno-research of a self-sufficient culture (1979-80). ©Archivio Alessandro Poli. Photo: Antonio Quattrone. Courtesy of the  [Image: Unknown engraver, Series of views showing the development of the modern bastion system from its medieval origins, Matthias Dögen (1647), courtesy of the

[Image: Unknown engraver, Series of views showing the development of the modern bastion system from its medieval origins, Matthias Dögen (1647), courtesy of the

[Image:

[Image:  [Image:

[Image:

[Images:

[Images:

[Images:

[Images:

[Images:

[Images:

[Images:

[Images:

[Image: From

[Image: From  [Image: From Paul Slade, “

[Image: From Paul Slade, “ [Image: From Paul Slade, “

[Image: From Paul Slade, “

[Image: “

[Image: “

[Images: “

[Images: “

[Images: “

[Images: “

[Images: “

[Images: “

[Images: “

[Images: “

[Image: “

[Image: “ [Image: “

[Image: “ [Image: “

[Image: “