According to a newly published report in the Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America, New York City is more at risk from earthquakes than previously thought.

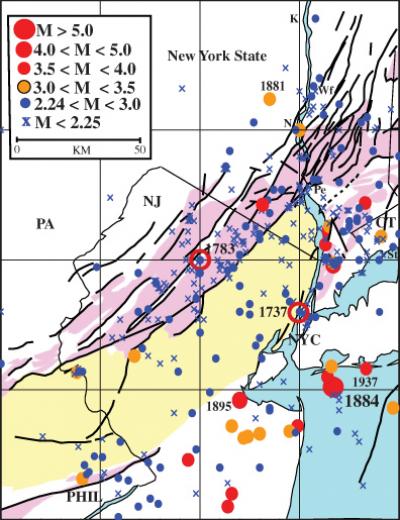

[Image: A seismic map of the mid-Atlantic, via PhysOrg.com].

[Image: A seismic map of the mid-Atlantic, via PhysOrg.com].

What’s interesting here, though, is not some disaster film scenario in which the city is shuddered into a rubble of broken bricks and glass, but the fact that the land around Manhattan is actually an “intricate labyrinth of old faults, sutures and zones of weakness caused by past collisions and rifting,” as PhysOrg.com describes it.

Amazingly, for anyone who has ever studied architecture, they even describe “unseen but potentially powerful structures whose layout and dynamics are only now coming clearer.” Gilles Deleuze must be rolling in his grave.

In a long excerpt, worth reading in full for its structural exploration of the land surrounding New York City, we read:

One major previously known feature, the Ramapo Seismic Zone, runs from eastern Pennsylvania to the mid-Hudson Valley, passing within a mile or two northwest of Indian Point. The researchers found that this system is not so much a single fracture as a braid of smaller ones, where quakes emanate from a set of still ill-defined faults. East and south of the Ramapo zone – and possibly more significant in terms of hazard – is a set of nearly parallel northwest-southeast faults. These include Manhattan’s 125th Street fault, which seems to have generated two small 1981 quakes, and could have been the source of the big 1737 quake; the Dyckman Street fault, which carried a magnitude 2 in 1989; the Mosholu Parkway fault; and the Dobbs Ferry fault in suburban Westchester, which generated the largest recent shock, a surprising magnitude 4.1, in 1985.

The 125th Street fault? The Dyckman Street fault? The Dobbs Ferry fault? It was already clear that the built geography of Manhattan has been thoroughly determined by tectonic prehistory, but what future faults might yet be discovered down there – an Empire State fault, a St. Mark’s Bookshop fault (with huge diagonal fissures extending infinitely down from the Critical Theory section), a Lower East Side fault whose all but imperceptible nighttime groaning gives new ideas to poets?

And shouldn’t these faults be added to Google Maps?

Some of these underground structures were actually discovered during excavation work for new subways and water tunnels beneath the city, when digging crews came across sudden breaks in the rock seeming to slice off to nowhere. But if these “ill-defined” interruptions, as PhysOrg.com describes them, in the foundational security of New York City lead anywhere, it is to a “braid of smaller [faults]” that filigrees throughout the area. The whole eastern seaboard around Manhattan becomes a puzzlework of forgotten microcontinents – and someday, again, that puzzle might start to move.

“Gilles Deleuze must be rolling in his grave.”

sigh. love the site, but these half-hearted philosophical namedrops aren’t adding much.

understandable, though: it’s much harder to actually work with that material than it is to make wannabe in-jokes…

roll in his grave he does.

Wow.

And the most pretentious comment on a blog oscar goes to…

Anonymous!

Hey, I live on Dyckman Street. Maybe this explains why the halal cart down the block seems to be getting farther away each day.

no, really, there is no reason why Deleuze should be invoked. The pretentiousness is all the author’s. Please don’t namedrop in such a facetious way, architecture is intellectually bankrupt as it is.

Murphy, if you think BLDGBLOG is pretentious, facetious, name-dropping, and intellectually bankrupt, why do you have a link to it on your site?

Anonymous, the funny thing is that I actually think the exact opposite of what you’ve written here: it is, in fact, unbelievably easy – in fact almost literally the easiest thing you could possibly do in architecture writing today – to take the exact same handful of quotations from Gilles Deleuze, from the exact same chapters of A Thousand Plateaus or Geophilosophy, and apply them more or less in the exact same way to questions of territoriality, nomadism, power, and so on. It takes little or no intellectual effort to use Deleuze quotations as a way to hide the fact that you have absolutely nothing to add to the architectural conversation. It’s politically expedient, sure – i.e. it’ll be easier to get a Ph.D. if you arbitrarily throw in some Deleuzian quotations about civil society – but it does nothing other than keep certain books in print at the expense of other (far more interesting) texts that aren’t trendy enough to survive a syllabus.

As it is, the fact that some random article about New York City seismology is more interesting than the collected works of Gilles Deleuze says an awful lot – both about seismology and certainly about Gilles Deleuze.

So if you don’t like unbelievably stupid – and blatantly unfunny – tossed-off jokes about dead philosophers, then you shouldn’t read this site. Because it’s going to happen again; I’m going to continue telling bad jokes. They won’t be even vaguely amusing, but they’ll allow me to feel like I’ve made a passing reference to something that was important to me at that moment.

Finally, if you want to hitch your car to the Deleuze citation-train then I’d suggest picking up literally any middle-of-the-road late 1990s/early 2000s architecture book – and then have a good time trying to find something interesting.

Geoff, touche, although;

I certainly don’t find you pretentious, facetious, name-dropping or intellectually bankrupt.

The aforementioned ‘tossed-off joke’ was some of those things, however…(!)

I’m just really touchy about bad deleuze, that’s all, for (roughly) the same reasons that you’ve just given above.

my apologies, do carry on…

I don’t know, I thought it was pretty funny.