[Image: Ruins of the City Walls (1625-1627) by Bartholomeus Breenbergh].

[Image: Ruins of the City Walls (1625-1627) by Bartholomeus Breenbergh].

In The Destruction of Memory: Architecture at War, Robert Bevan describes, in almost numbing detail, how specific buildings – indeed, whole cities – have been targeted, damaged, or otherwise destroyed by war.

He writes of the “violent destruction of buildings for other than pragmatic reasons,” claiming that “there has always been [a] war against architecture.” This war is fought through the deliberate “eradication” of an enemy’s built environment – that is, “the active and often systematic destruction of particular building types or architectural traditions.”

Some of Bevan’s examples, however, sound less like warfare than a kind of highly complex – and extremely violent – architectural ritual, played out over centuries between rival governments and religions. This is the “repeated demolition or adaptation of each other’s buildings,” and retaliation can sometimes take generations.

For instance, Bevan writes about the site of the cathedral, in Córdoba, Spain, which “started out as a Roman temple” before being destroyed by Christian Visigoths:

A subsequent church on the site was replaced by a mosque following the Arab conquest of the early eighth century. Some seventy years later this was itself demolished to create the first stage of a massive new mosque. The Christian recaptured Córdoba in 1236 and consecrated the building as a cathedral. (…) It is said that the mosque’s lamps were melted down to make new bells for the cathedral of Santiago de Compostela, 800 km to the north. This probably seemed only fair, since the lamps had themselves been made from Santiago’s original bells: when the Moors had conquered the city in 997 they had dragged the bells to Córdoba and melted them down into lamps.

Tit for tat.

Bevan also describes how the Bastille, having been stormed in 1789, was reduced to a heap of stones – but these stones were then “broken up and sold as souvenirs,” in a “commodification process repeated with the fragments of the Berlin Wall 200 years later.”

In any case, Bevan goes on to discuss mosques bulldozed in the Balkans, synagogues burnt to the ground in both Poland and Germany, Armenian monasteries reduced to foundation stones as, even today, they are dismantled and reused to build houses in eastern Turkey, the dynamiting of Loyalist mansions by Irish Republican militias, the destruction of the World Trade Center, and even archaeological sites fatally disturbed during the invasion of Iraq – among many, many other such examples, all found throughout Bevan’s book.

These are all, he says, “crimes against architecture.”

More to the point here, when Bevan points out that “the bulldozed remains of the Aladza mosque” were “dumped” by Serbian troops into a nearby river – the ruins were only “identified by the mosque’s distinctive stone columns” – it occurred to me that fragments like these must be numerous enough that you could use them to reassemble complete buildings elsewhere.

More to the point here, when Bevan points out that “the bulldozed remains of the Aladza mosque” were “dumped” by Serbian troops into a nearby river – the ruins were only “identified by the mosque’s distinctive stone columns” – it occurred to me that fragments like these must be numerous enough that you could use them to reassemble complete buildings elsewhere.

You could construct a whole city from fragments of buildings destroyed by war.

For instance, all the gravel, dirt, and foundation stones from ruined buildings and cities around the world could be dropped into shallow waters off the western coast of Greece – forming the base of an artificial island, as large as Manhattan, on which to build your memorial to cities and spaces killed by war…

For instance, all the gravel, dirt, and foundation stones from ruined buildings and cities around the world could be dropped into shallow waters off the western coast of Greece – forming the base of an artificial island, as large as Manhattan, on which to build your memorial to cities and spaces killed by war…

You draw up plans with a local architecture school, plotting a whole new island metropolis constructed from nothing but pre-existing pieces of annihilated architecture – fitting arches with arches and floors with floors.

Within a decade you’ve covered the island in a maze of Chicago tenement housing, Russian churches, Indian temples, and Chinese hutongs; there are Aztec walls and pillars standing inside reconstructed Romanian state houses – before most of pre-WWII Europe begins to appear, together with shattered castles, north African villages, and the weathered masonry of pre-Columbian South America, all the buildings merging one into one another, indistinct, with Mayan rocks and Kurdish roofing joined together atop bricks from Köln and Dresden.

Another decade later and the island-city is complete. There are no cars and no electricity – in fact, no one lives there at all. It sits alone in the waters, covered in wild herbs and home to songbirds, casting shadows on itself, eroding a bit in the occasional rainstorm.

Documentaries about it soon appear on CNN and the BBC.

Only 10 people are allowed on the island at any given time; most of them just take photographs or make sketches, or write letters to loved ones, as they wander, awe-struck, through the narrow streets of this barely remembered desolation, stumbling upon extinct building types and lost statuary – towers of churches destroyed by bombs – hardly even able to conceive how all these places could have been destroyed by human conflict.

They then brush the dust of structures off their shoes as they board the boat to go home, silent, looking back at this island, the sun setting a brilliant orange behind its almost pitch-black silhouette.

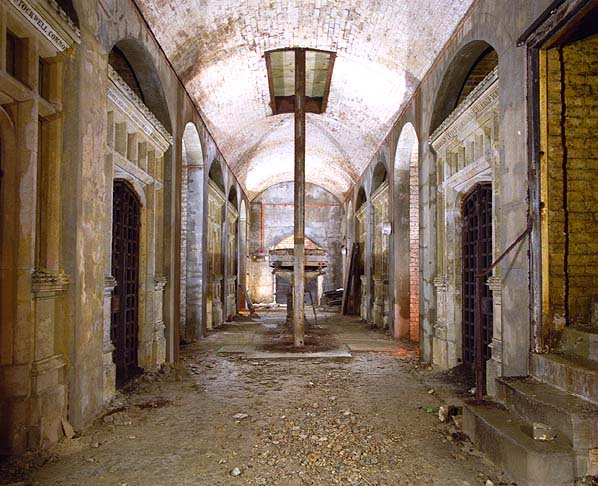

[Image: A scene from Peter Kidger’s The Berlin Infection, produced as part of Kidger’s work with the Bartlett School of Architecture’s Unit 15 in London].

[Image: A scene from Peter Kidger’s The Berlin Infection, produced as part of Kidger’s work with the Bartlett School of Architecture’s Unit 15 in London]. [Image: Outside the wind tunnel – a building rehabbed by Daly Genik. More info about it here].

[Image: Outside the wind tunnel – a building rehabbed by Daly Genik. More info about it here]. [Image: An underground “coffin lift or ‘catafalque’,” from London’s

[Image: An underground “coffin lift or ‘catafalque’,” from London’s  [Images: Photos by Neil Burns capture the destruction; via the

[Images: Photos by Neil Burns capture the destruction; via the

[Images: Photos by Andrew Turner and John Smith; via the

[Images: Photos by Andrew Turner and John Smith; via the  [Images: Via

[Images: Via  And so I was thinking today that you could go around Manhattan with a microphone, asking people who have had that dream to describe it, recording all this, live, for the radio – or you ask people who have never had that dream simply to ad lib about what it might be like to discover another room, and you ask them to think about what kind of room they would most like to discover, tucked away inside a closet somewhere in their apartment.

And so I was thinking today that you could go around Manhattan with a microphone, asking people who have had that dream to describe it, recording all this, live, for the radio – or you ask people who have never had that dream simply to ad lib about what it might be like to discover another room, and you ask them to think about what kind of room they would most like to discover, tucked away inside a closet somewhere in their apartment. [Image: From the series

[Image: From the series  [Image: From the series

[Image: From the series  [Image: From the series

[Image: From the series  [Image: From the series

[Image: From the series  According to the BBC, Indian officials have concluded that a “

According to the BBC, Indian officials have concluded that a “ A poster for

A poster for  [Image: Courtesy of

[Image: Courtesy of  A bachelor is alone, after all, which means that “so much the smaller a space is considered sufficient for him.”

A bachelor is alone, after all, which means that “so much the smaller a space is considered sufficient for him.” [Image:

[Image:  More to the point here, when Bevan points out that “the bulldozed remains of the

More to the point here, when Bevan points out that “the bulldozed remains of the  For instance, all the gravel, dirt, and foundation stones from ruined buildings and cities around the world could be dropped into shallow waters off the western coast of Greece – forming the base of an artificial island, as large as Manhattan, on which to build your memorial to cities and spaces killed by war…

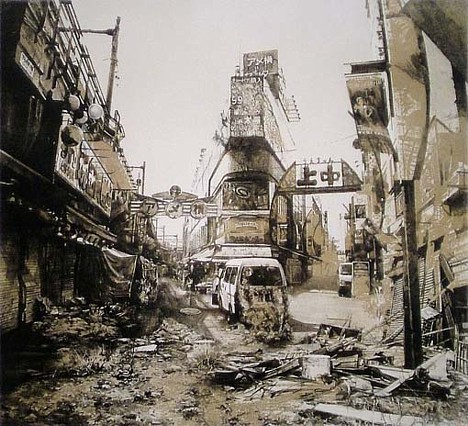

For instance, all the gravel, dirt, and foundation stones from ruined buildings and cities around the world could be dropped into shallow waters off the western coast of Greece – forming the base of an artificial island, as large as Manhattan, on which to build your memorial to cities and spaces killed by war…  [Image: Ameyoko by

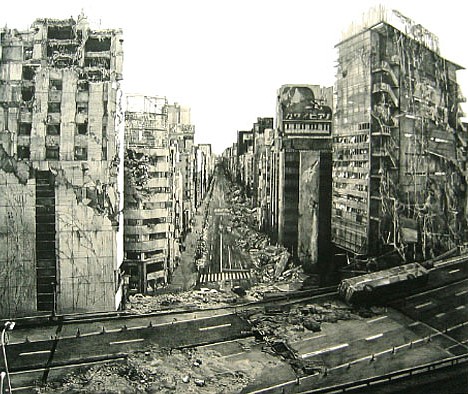

[Image: Ameyoko by  [Image: Ginza Chuo Dori by

[Image: Ginza Chuo Dori by

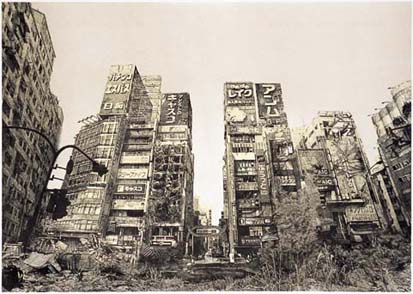

[Images: Kabukicho, Shibuya Center Town, and Electric City by

[Images: Kabukicho, Shibuya Center Town, and Electric City by  [Image: Hashima by

[Image: Hashima by