Or Dubai after and before: it’s a somewhat jaw-dropping look at the Sheikh Zayed Road, prior to and after the recent building boom. Photographer and source unknown. (If you know, leave a comment).

Year: 2005

Wormholes

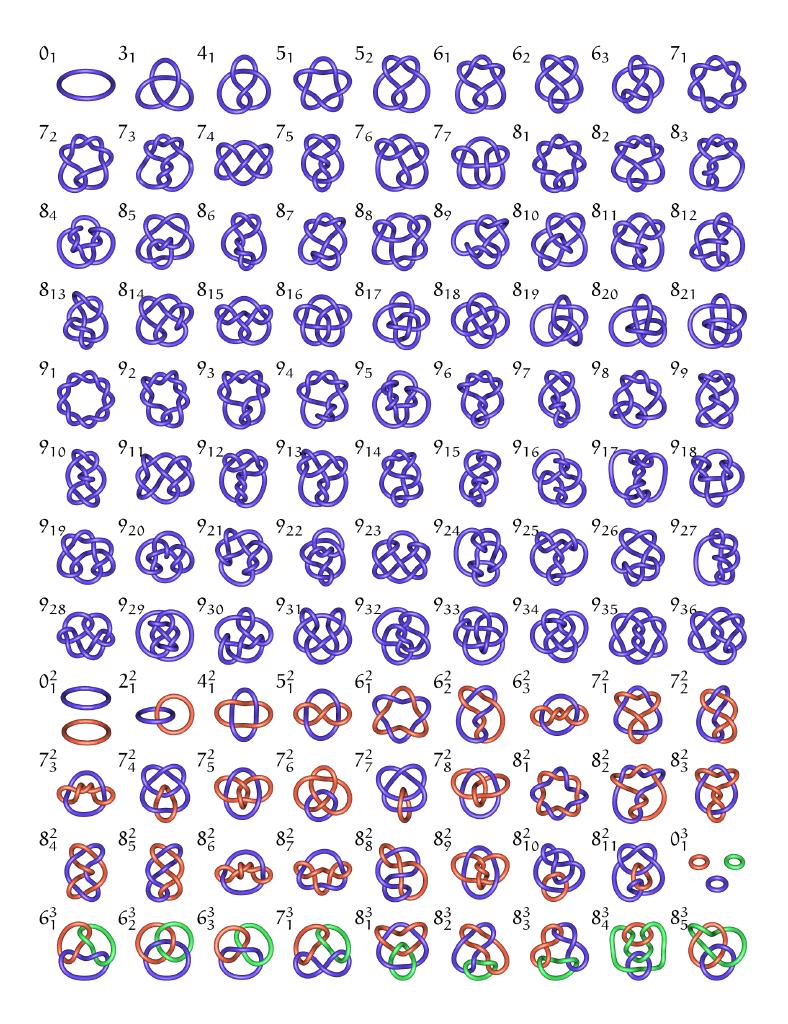

I was at a talk the other night listening to a nervous grad student present a paper about knots when, for whatever reason – I was thinking about Michael Heizer – wham!

I was at a talk the other night listening to a nervous grad student present a paper about knots when, for whatever reason – I was thinking about Michael Heizer – wham!

An idea came to me:

The eccentric son of a billionaire takes his share of the family fortune and moves to Utah. He buys loads and loads of land, tens of thousands of acres – and, with it, huge digging machines.

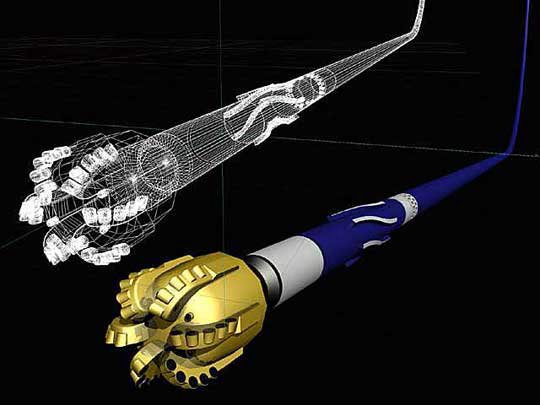

This includes state of the art tunnelers, taken straight from the oil industry.

[Image: Create 3D].

[Image: Create 3D].

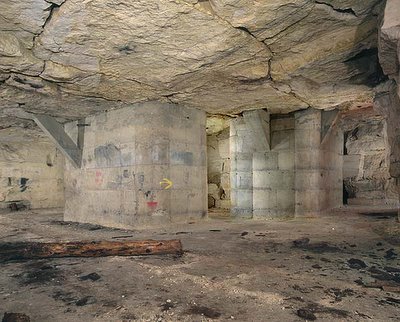

For the next forty years, one thousand feet below the surface of the earth, he carves every knot known to mathematics, straight through the Jurassic bedrock. They form tunnels, loops, topology; big enough to walk through.

The man makes his way down the list, one by one, carving, tunneling, blasting.

Smooth and toroidal, they are negative sculptures, a textbook in knot theory. They can be studied. Mathematics can be derived from their curves. In two hundred years they will be declared a National Park.

At night, when the man can’t sleep, he walks the knots, lonely, underground, sometimes humming.

The knots reverberate.

Churches of the void-grinder

In 1999, Swiss architect Mario Botta was commissioned to design a model of Francesco Borromini’s Church of San Carlo alle Quattro Fontane, in Rome.

In 1999, Swiss architect Mario Botta was commissioned to design a model of Francesco Borromini’s Church of San Carlo alle Quattro Fontane, in Rome.

Called San Carlino, Botta’s model – part building, part sculpture – was erected near Borromini’s own birthplace, on the shores of Lake Lugano, to celebrate the 400th anniversary of Borromini’s birth.

The work was dismantled in 2003.

The project was made using 35,000 wood boards, each of which was cut, milled, and sanded, then assembled with the rest to reproduce the exact internal volume of Borromini’s church.

Well, half of Borromini’s church.

The interior, in other words, was carved out of this colossus of wood; the space of the church was milled, excavated from the stacked material.

This virtual walk-through gives a nice, if badly lit, sense of the abrupt edge Botta designed for the model –

– because as you can see from Botta’s own sketch, below, he effectively cut the church in half; measured the internal volume down to the scale of centimeters; then reproduced that void using 35,000 specially cut boards.

Certain photographs I’ve seen are actually quite astonishing; the freshly cut boards in the earliest photographs all but glow compared to the coal-black exterior, and the blue skies of Lugano add a surreal backdrop to the unexpected sight of the semi-sacred hollow.

I have to admit, however, that when I first saw those photographs I did not understand what I was looking at. My first reaction was fairly predictable, I suppose, and that was to picture a huge milling-machine, built to the exact volume and measurements of Borromini’s church – a kind of void-grinder several stories high, whirring with precise blades and abraders, like some massive (perhaps consecrated) mining machine.

That would, of course, be ridiculous; but it got me thinking.

I wondered if you could precisely measure the interior space of Notre-Dame, for instance, then build or program an industrial-scale grinding machine to those exact specifications. A kind of inside-out abrader. A void-grinder. You could then park that thing in front of a mountain and lo! Three hours later the exact internal dimensions of Notre-Dame – the hollows and side-chapels, the soaring interior of cross-vaults – have been carved, in real size, into the granite surface of the Teton Range.

You can walk into that hollow, light a candle, and be damned if it doesn’t look exactly like the real thing…

In fact, you could do this for any cathedral on the planet. Measure its exact interior volume, using lasers perhaps, and then use those measurements to fabricate a grinding-machine. Then choose your target: the interior of Chartres, for instance, could be carved into the quartz-belted strata of the Canadian Rockies. The interior of St. Paul’s whirred and abraded into the mountains of Bamiyan, where the Buddhas once stood.

You could even map out, to the millimeter, the internal volume of every cathedral, mosque, and temple in the world, and then program that into a robotic rock-milling machine. You then send that machine to the moon where, over the course of two generations, it carves the exact, to-scale internal voids of beautiful sacred architecture into the lunar surface.

From the earth it looks as if small caves are appearing on the moon, like sink-holes or new craters – but you take out your telescope, walk into the backyard with your friends, look up, and, there, hollowed out, void-black on the moon, are hollow reproductions of Chartres Cathedral, Salisbury, Hagia Sophia, Angkor Wat.

Future lunar expeditions go torchlit through those caves, re-breathing tanked oxygen: what were these things…? What built them…?

Silicon Gardens

Pruned has been posting some great things lately, but yesterday’s feature just blew me away: it’s a tropical garden by artist Marc Quinn, whose flowers “are immersed in twenty-five tons of liquid silicon kept at a constant temperature of -80˚ Celsius.” (Though that should read silicone – the same material used in breast implants…)

The silicone has the effect of freezing time: the flowers, though dead, will never decay. (Till someone turns the refrigerator off).

They’ve been mummified. An entire landscape has been mummified.

As Quinn himself explains, using all lowercase and some interesting punctuation: “those who visited the installation found themselves, thanks to mirrors, in a garden of infinite beauty and immortality. an enviroment created by plants from various continents -asia, africa-europe- and from different seasons, beauty that doesn’t decay. a perfect image beyond botany itself. these flowers will last forever, but obviously they are dead. the installation in a 3,20 m x 12,70 m x 5,43 m stainless steel refrigerator (-20°C) is technically made of flowers frozen in a silicon oil. (which stays liquid to – 80°C and doesn’t chemically react with the flowers)”

The landscape has been embalmed.

The mind reels.

Could you embalm a riverbed, for instance, to freeze that hydrology in place, its weeds, and erosion, its gravel? Or – here’s the thing: could you go round embalming natural plantlife everywhere – say a developer is encroaching upon some (relatively) untouched hills in the Cotswolds, but here you come, carrying your silicon-embalming tools, hitching up your trousers, and you freeze 5’x5’x5′ cubes of the natural landscape. In place.

Museums of the remnant landscape.

Once all the houses are finally built and everyone moves in, kids find themselves playing beside cubes of mummified plantlife. Garden cubes. Landscape fossils. Embalmed landscapes.

Silicon gardens.

(The trick would be to do this for millions and millions of years, like a landscape time-capsule: here, for instance, outside the BLDGBLOG head office, would be small Jurassic shrubs frozen in liquid silicon; in the middle of the Sahara you’d find tropical orchids, locked in cubes, older than the Himalayas – remnant landscapes preserved…)

London Topological

[Image: Embankment, London, ©urban75].

[Image: Embankment, London, ©urban75].

As something of a sequel to BLDGBLOG’s earlier post, Britain of Drains, we re-enter the sub-Britannic topology of interlinked tunnels, drains, sewers, Tubes and bunkers that curve beneath London, Greater London, England and the whole UK, in rhizomic tangles of unmappable, self-intersecting whorls.

[Images: The Bunker Drain, Warrington; and the Motherload Complex, Bristol (River Frome Inlets); brought to you by the steroidally courageous and photographically excellent nutters at International Urban Glow].

[Images: The Bunker Drain, Warrington; and the Motherload Complex, Bristol (River Frome Inlets); brought to you by the steroidally courageous and photographically excellent nutters at International Urban Glow].

Whether worm-eaten by caves, weakened by sink-holes, rattled by the Tube or even sculpted from the inside-out by secret government bunkers – yes, secret government bunkers – the English earth is porous.

“The heart of modern London,” Antony Clayton writes, “contains a vast clandestine underworld of tunnels, telephone exchanges, nuclear bunkers and control centres… [s]ome of which are well documented, but the existence of others can be surmised only from careful scrutiny of government reports and accounts and occassional accidental disclosures reported in the news media.”

[Images: Down Street, London, by the impressively omnipresent Nick Catford, for Subterranea Britannica; I particularly love the multi-directional valve-like side-routes of the fourth photograph].

[Images: Down Street, London, by the impressively omnipresent Nick Catford, for Subterranea Britannica; I particularly love the multi-directional valve-like side-routes of the fourth photograph].

This unofficially real underground world pops up in some very unlikely places: according to Clayton, there is an electricity sub-station beneath Leicester Square which “is entered by a disguised trap door to the left of the Half Price Ticket Booth, a structure that also doubles as a ventilation shaft.”

This links onward to “a new 1 1/4 mile tunnel that connects it with another substation at Duke Street near Grosvenor Square.”

But that’s not the only disguised ventilation shaft: don’t forget the “dummy houses,” for instance, at 23-24 Leinster Gardens, London. Mere façades, they aren’t buildings at all, but vents for the underworld, disguised as faux-Georgian flats.

(This reminds me, of course, of a scene from Foucault’s Pendulum, where the narrator is told that, “People walk by and they don’t know the truth… That the house is a fake. It’s a façade, an enclosure with no room, no interior. It is really a chimney, a ventilation flue that serves to release the vapors of the regional Métro. And once you know this you feel you are standing at the mouth of the underworld…”).

[Image: The Motherload Complex, Bristol – again, by International Urban Glow].

[Image: The Motherload Complex, Bristol – again, by International Urban Glow].

There is also a utility subway – I love this one – accessed “through a door in the base of Boudicca’s statue near Westminster Bridge.” (!) The tunnel itself “runs all the way to Blackfriars and then to the Bank of England.”

Et cetera.

[Images: The Works Drain, Manchester; International Urban Glow].

[Images: The Works Drain, Manchester; International Urban Glow].

My personal favorite by far, however, is British investigative journalist Duncan Campbell’s December 1980 piece for the New Statesman, now something of a cult classic in Urban Exploration circles.

[Image: Motherload Complex, Bristol; International Urban Glow].

[Image: Motherload Complex, Bristol; International Urban Glow].

“Entering, without permission, from an access shaft situated on a traffic island in Bethnal Green Road he descended one hundred feet to meet a tunnel, designated L, stretching into the distance and strung with cables and lights.” He had, in other words, discovered a government bunker complex that stretched all the way to Whitehall.

On and on he went, all day, for hours, riding a folding bicycle through this concrete, looking-glass world of alphabetic cyphers and location codes, the subterranean military abstract: “From Tunnel G, Tunnel M leads to Fleet Street and P travels under Leicester Square to the then Post Office Tower, with Tunnel S crossing beneath the river to Waterloo.”

[Image: Like the final scene from a subterranean remake of Jacob’s Ladder (or a deleted scene from Creep [cheers, Timo]), it’s the Barnton Quarry, ROTOR Drain, Edinburgh; International Urban Glow].

[Image: Like the final scene from a subterranean remake of Jacob’s Ladder (or a deleted scene from Creep [cheers, Timo]), it’s the Barnton Quarry, ROTOR Drain, Edinburgh; International Urban Glow].

Here, giving evidence of Clayton’s “accidental disclosures reported in the news media,” we read that “when the IMAX cinema inside the roundabout outside Waterloo station was being constructed the contractor’s requests to deep-pile the foundations were refused, probably owing to the continued presence of [Tunnel S].”

[Image: Motherload, Bristol; International Urban Glow].

[Image: Motherload, Bristol; International Urban Glow].

But when your real estate is swiss-cheesed and under-torqued by an unreal world of remnant topologies, the lesson, I suppose, is you have to read between the lines.

A simple building permissions refusal might be something else entirely: “It was reported,” Clayton says, “that in the planning stage of the Jubilee Line Extension official resistance had been encountered, when several projected routes through Westminster were rejected without an explanation, although no potential subterranean obstructions were indicated on the planners’ maps. According to one source, ‘…the rumour is that there is a vast bunker down there, which the government has kept secret, which is the grandaddy of them all.'”

[Image: The Corsham Tunnels; see also BLDGBLOG].

[Image: The Corsham Tunnels; see also BLDGBLOG].

Continuing to read between the lines, Clayton describes how, in 1993, after “close scrutiny of the annual Defence Works Services budget the existence of the so-called Pindar Project was revealed, a plan for a nuclear bomb-proof bunker, that had cost £66 million to excavate.”

All of these places have insane names—Pindar, Cobra, Trawlerman, ICARUS, Kingsway, Paddock—and they are hidden in the most unlikely places. Referring to a government bunker hidden in the ground near Reading: “Inside, they tried another door on what looked like a cupboard. This was also unlocked, and swung open to reveal a steep staircase leading into an underground office complex.”

[Images: The freaky stairs and tunnels, encrusted with plaster stalactites, of King William Street].

[Images: The freaky stairs and tunnels, encrusted with plaster stalactites, of King William Street].

Everything leads to everything else; there are doorways everywhere. It’s like a version of London rebuilt to entertain quantum physicists, with a dizzying self-intersection of systems hitting systems as layers of the city collide.

[Image: Belsize Park, from the terrifically useful Underground History of Hywel Williams].

[Image: Belsize Park, from the terrifically useful Underground History of Hywel Williams].

There is always another direction to turn.

[Image: The Shorts Brothers Seaplane Factory and air raid shelter, Kent; photo by Underground Kent].

[Image: The Shorts Brothers Seaplane Factory and air raid shelter, Kent; photo by Underground Kent].

This really could go on and on; there are flood control complexes, buried archives, lost rivers sealed inside concrete viaducts – and all of this within the confines of Greater London.

[Images: London’s Camden catacombs – “built in the 19th Century as stables for horses… [t]heir route can be traced from the distinctive cast-iron grilles set at regular intervals into the road surface; originally the only source of light for the horses below” – as photographed by Nick Catford of Subterranea Brittanica].

[Images: London’s Camden catacombs – “built in the 19th Century as stables for horses… [t]heir route can be traced from the distinctive cast-iron grilles set at regular intervals into the road surface; originally the only source of light for the horses below” – as photographed by Nick Catford of Subterranea Brittanica].

Then there’s Bristol, Manchester, Edinburgh, Kent…

[Image: Main Junction, Bunker Drain, Warrington; International Urban Glow].

[Image: Main Junction, Bunker Drain, Warrington; International Urban Glow].

And for all of that, I haven’t even mentioned the so-called CTRL Project (the Channel Tunnel Rail Link); or Quatermass and the Pit, an old sci-fi film where deep tunnel Tube construction teams unearth a UFO; or the future possibilities such material all but demands.

[Image: Wapping Tunnel Vent, Liverpool, by International Urban Glow; a kind of subterranean Pantheon].

[Image: Wapping Tunnel Vent, Liverpool, by International Urban Glow; a kind of subterranean Pantheon].

Such as: BLDGBLOG: The Game, produced by LucasArts, set in the cross-linked passages of subterranean London, where it’s you, a torch, some kind of weapon, a shitty map and hordes of bird flu infected zombies coughing their way down the dripping passages – looking for you…

Floating islands gone wild

[Image: Photo by Jodi Hilton for the New York Times].

[Image: Photo by Jodi Hilton for the New York Times].

An ominous, mobile island in Massachusetts “has been floating for as long as anyone can remember, buoyed by a mat of sphagnum moss and gases from decomposing plants. It is a curiosity and sometimes a nuisance” – because it has quite a temper.

“‘Normally when it floats you can actually hear the roots rip – it sounds like ripping up carpet,’ said [Andrew] Renna, 51, a roofing and siding sales manager. ‘But this time, it didn’t make any noise.'”

“This time,” that is, it crept over, floating, silent but deadly, and it crushed Mr. Renna’s tomatoes.

“Sometimes it boings mischievously around,” the New York Times explains, “as if the pond were a pinball machine, sailing, for example, into Richard and Beverly Vears’s backyard just hours after they moved in.”

Thus began a whole new genre of practical joke: the terrestrial psych-out.

The island’s new position in the Vears’s backyard “gave a neighbor a perfect welcome gag: telling the Vearses he was a tax collector who would charge them for the extra property.”

[Image: Infographic courtesy of the New York Times].

[Image: Infographic courtesy of the New York Times].

This and other such “floating bogs” have been anchored, moored, tied-up, chained, even towed away by speedboats (giving Robert Smithson quite a run for his money) – but they just keep breaking free.

Sometimes their unstoppable urge for tectonic liberation calls for nothing less than “extreme island annihilation.”

[Image: Photo by Alex Quesada for the New York Times].

[Image: Photo by Alex Quesada for the New York Times].

Islands such as these “usually form in wetlands, where plants take root in peaty soil or sphagnum moss in a shallow lake or riverbed, said Dave Walker, a senior project manager with the St. Johns River Water Management District in Florida, where, he said, ‘you can get acres and acres of floating islands on a lake.'”

Fascinatingly, “[s]ome experts believe that floating islands are becoming more common or lasting longer in some places, especially where human encroachment has created reservoirs or where fertilizer use has made certain plants grow faster.”

In any case, you can actually buy these things, or have them made for you – this is referred to as “island deployment” – and you can get them customized, as well. Pimp My Floating Bog.

You are, in fact, urged to “Think about it. Dream about it. Experience it yourself” – leading one to wonder what “it” really is.

earth.mov

Who knew how fun the US government could be?

Because here they’ve given us a downloadable origami earth balloon that would make Buckminster Fuller faint out of sheer professional jealousy –

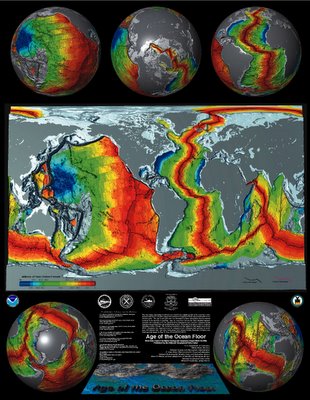

[Image: National Geophysical Data Center – also available as a dodecahedron].

– a rad little animation of the December 2004 tsunami, and this crazy-color poster that depicts the tectonic ages of the earth’s ocean crust –

[Image: National Geophysical Data Center].

– this last one available in a whopping 12.5MB poster.

Surely a whole book could be written about the United States government and its encounter with the earth? An oral history of the US Geological Survey. An ethnography of the Department of the Interior.

How the State manages its terrestrial other.

Law against Geology.

The coming of the mega-eco-engineer

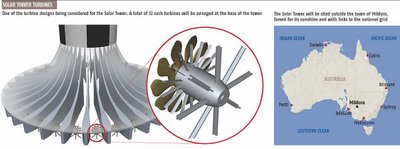

“If this concrete structure makes it off the drawing board,” the New Scientist says, “it will smash every record in the book. It will stand a staggering 1 kilometre tall, and its base will sit at the centre of a shimmering field of glass and plastic 7 kilometres across.”

So what is it?

If built, it will be “Australia’s biggest solar power plant,” a kind of chimney for hot light.

“Air heated by the sun will rise up the tower, where 32 turbines will generate about 650 gigawatt-hours of electricity a year, enough to meet the demands of 70,000 Australians.”

And if it sounds novel – it isn’t. “People have been harnessing the energy of rising columns of air for centuries,” we’re reminded.

As recently as the 1980s, for instance, a similar tower was constructed in Manzanares, Spain: “Rising 195 metres into the air and surrounded by an array of plastic sheeting 240 metres across, the Manzanares tower proved the concept worked. The plastic sunlight collector warmed the air underneath by up to 17°C, enough to draw it towards the central tower, where it created a strong enough updraught to drive a turbine and generate electricity. There were no fuel costs to pay, and no climate-damaging greenhouse-gas emissions.”

The efficiency of such a tower, we learn, “can be increased by using a larger collector to increase the air temperature at the base. And the taller the tower, the lower the ambient atmospheric pressure at the top.” This means that a “1000-metre tower will be five times as efficient as the 200-metre Manzanares tower.”

The taller the better.

Such a project is not without problems, however, “such as how to keep some 4000 hectares of greenhouse [at the foot of the tower, where the air is heated] clean enough to trap solar radiation in the first place. Legions of squeegee-wielding window cleaners will clearly not be the answer. And there are worries that the plastic sheets used to build the collector might deteriorate under the glare of the Australian sun, as they did in Manzanares.”

On the other hand, nothing is without its difficulties, and concerns of basically any kind at all are not holding back the scientists behind this and other so-called “mega-engineering” projects.

Global warming? We’ll just build huge mirrors, or use reflective balloons, to bounce all that extra solar energy back into space.

“Edward Teller,” for instance, “father of the hydrogen bomb… [once] proposed putting shards of metal or specially made ‘optical resonant scatterers’, which reflect light of particular wavelengths, into the stratosphere.”

Apparently all you’d need is “a million tonnes of tiny aluminium balloons, each around 4 millimetres across, filled with hydrogen and floated into the stratosphere… for as little as a billion dollars a year.” Not that tiny, metal balloons filled with hydrogen could interfere with wildlife, or fall into the oceans, but hey: just picture it – millions of little silver balloons floating through the stratosphere…

Installation art as climatic engineering. Or vice versa.

One wonders what else is under consideration.

How about the giant space-mirror?

Lowell Wood, at the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, wants to build “a giant diaphanous mirror in space a thousand kilometres across (!) and park it between the sun and the Earth to reflect solar radiation away from our atmosphere. Some 3000 tonnes of shield could compensate for a doubling of CO2 levels. The cost could run into hundreds of billions of dollars.”

3000 tonnes of shield – is not a phrase you read very often.

So what else could we do?

We could try “spreading billions of small reflecting objects, such as white golf balls, across the tropical oceans;” and if “golf balls and space mirrors prove to be too far-fetched, John Latham of the US government’s National Center for Atmospheric Research in Boulder, Colorado, has suggested a more down-to-earth option: making clouds whiter.”

Sounds down-to-earth to me.

But how does it work?

Latham, we read, “calculates that doubling the number of droplets in clouds over all the world’s oceans would shut down several decades of global warming. Ingeniously, he proposes doing this by deploying giant wind-powered machines” – one of which “looks rather like a giant egg whisk” – “to fling salt spray from the sea into the air.” (Incredibly, this machine was designed by a man named Salter).

“A full-size version would be 70 metres high, and hundreds of them across the oceans could whiten clouds across thousands of kilometres.”

Godzilla v. The Cloud-Salter.

Then there’s Klaus Lackner, recently featured in the Alanis Morissette-narrated “Global Warming” TV special. Lackner is a scientist at Columbia University, and he has proposed the construction of massive “forests” made from synthetic trees.

According to Lackner, each synthetic tree would look “like a goal post with Venetian blinds,” not like a tree at all.

[Image: Columbia University Earth Institute].

“But the synthetic tree would do the job of a real tree… It would draw carbon dioxide out of the air, as plants do during photosynthesis, but retain the carbon and not release oxygen.”

Each tree, as the BBC describes it, “would act like a filter. An absorbent coating, such as limewater, on its slats or ‘leaves’ would seize carbon dioxide and retain the carbon. Dr Lackner predicts that the biggest expense would be in recycling the absorber material.”

The catch is that you would need at least 250,000 of these “goal posts with Venetian blinds” studded all over the earth, located inside cities, standing like optical illusions receding over the horizon. (Smaller, domestic versions are under consideration).

In any case, all of these eco-friendly (or almost) mega-projects are barely a fraction of the actual proposals out there, passing from one desk to the next, being sent via email from one mega-engineering firm after the other, getting filed away or submitted to venture capital firms.

Yet I’m tempted to issue a call of sorts here: that any BLDGBLOG reader who gets a kick out these ideas – building artificial, carbon-absorbant forests, for instance, or the giant space-mirror (I like the tiny balloons) – should perhaps scan the classified ads each week to see if war-profiteer/engineering firms like Halliburton, Anteon, Northrop-Grumman, and their ilk are hiring.

Then get a job there, work your way to the top, and pull out of the war industries altogether.

Start building solar towers, and absorbant forests, and, while you’re at it, pump millions of dollars into modular architecture and prefab housing, not for more military training villages, but to build refugee camps and post-disaster instant cities, realizing the goals of Archigram, Greenpeace, and Architecture for Humanity, all at once.

Just a thought.

(And if you have your own mega-eco-ideas… leave a comment, below).

Mirny Mine, pt. 2

Adding to BLDGBLOG’s earlier photographs of the Mirny Mine, here is one more – in a highly suspect color scheme – as pointed out to me by Anonymous.

A substantially larger version is available if you click on the image –

– which also reveals the rather astonishing difference in scale between the city and the hole itself, which, of course, is the world’s largest diamond mine.

The photograph, meanwhile, reminded me of something my friend Dan once told me, that an American scientist had devised a plan to use, yes, nuclear bombs to open up a hole in the earth’s crust. Nuclear bombs.

Turns out, it’s Caltech’s David Stevenson, whose plan “involves creating a crack in the Earth’s crust either by detonating a nuclear warhead or by using something which would release a similar amount of energy.”

[Image: BBC].

[Image: BBC].

As Stevenson himself explained to the BBC: “You fill that crack quickly with liquid iron and with a small, solid probe immersed in that liquid iron. The probe would be perhaps the size of a grapefruit. The iron being heavier than the surrounding rock causes the crack to keep propagating down and closing up behind as it does so. It goes down to the Earth’s core at quite high speed, on a timescale of days. As it reaches the core, the probe will send back, using seismic signals, information about what the Earth is made of.”

Surely, then, it would be worth nuking a self-propagating crack into the earth’s crust? What could possibly go wrong?

Turns out he’s kidding – sort of. (See PDF).

Embrace the meatscape

[Image: Sunset with Hamhocks; this and all images below by Nicolas Lampert].

More foodscaping, this time huge piles of meat collaged into the background of 1960s-era postcard-like landscapes by artist Nicolas Lampert:

[Image: Meatscape #2].

[Image: Meatscape].

[Image: Public Meat Art].

[Image: Meat Square].

And any struggling, culinarily-inspired collagists out there who want to produce a series of BLDGBLOG foodscapes… let us know.

(Via Boing Boing).

Subterranean bunker-cities

[Image: A map of Wiltshire’s Ridge quarry/bunker system; see below].

An article I’ve not only forwarded to several people but planned whole screenplays around, frankly, reveals that there is a sprawling complex of tunnels located beneath Belgrade.

There, a recent police investigation “into the mysterious shooting of two soldiers has revealed the existence beneath the Serbian capital of a secret communist-era network of tunnels and bunkers that could have served as recent hideouts for some of the world’s most-wanted war crimes suspects. The 2-square-mile complex – dubbed a ‘concrete underground city’ by the local media – was built deep inside a rocky hill in a residential area of Belgrade in the 1960s on the orders of communist strongman Josip Broz Tito. Until recently its existence was known only to senior military commanders and politicians.”

So how big is this concrete underground city?

“Tunnels stretching for hundreds of yards link palaces, bunkers and safe houses. Rooms are separated by steel vault doors 10 feet high and a foot thick. The complex has its own power supply and ventilation.”

But hundreds of yards? That’s nothing.

A secret, 240-acre underground bunker-city has recently come onto the UK housing market.

With 60 miles of tunnels, located 120 feet underground, the whole complex is worth about 5 million quid.

The complex was constructed “in a former mine near Corsham in Wiltshire where stone was once excavated… for the fine houses of Bath.”

This subterranean city, as the Times tells us, “was a munitions dump and a factory for military aircraft engines. It was equipped with what was then the second largest telephone exchange in Britain and a BBC studio from where the prime minister could make broadcasts to what remained of the nation.”

Radio broadcasts echoing across a landscape of craters.

[A note on these images: these are all photographs – by the very talented and highly prolific Nick Catford – of the Ridge Quarry, in Corsham, Wiltshire, which geographically matches with the Times description, above. That said, the description of the Ridge Quarry provided by Subterranea Britannica does not seem to indicate that we are, in fact, looking at the same mine/quarry/bunker system. (There is a discrepancy in the amount of acreage, for instance). Anyone out there with info, thoughts, or other et ceteras, please feel free to comment… Either way, however, they’re cool images, and Subterranea Britannica is always worth a visit now and again].