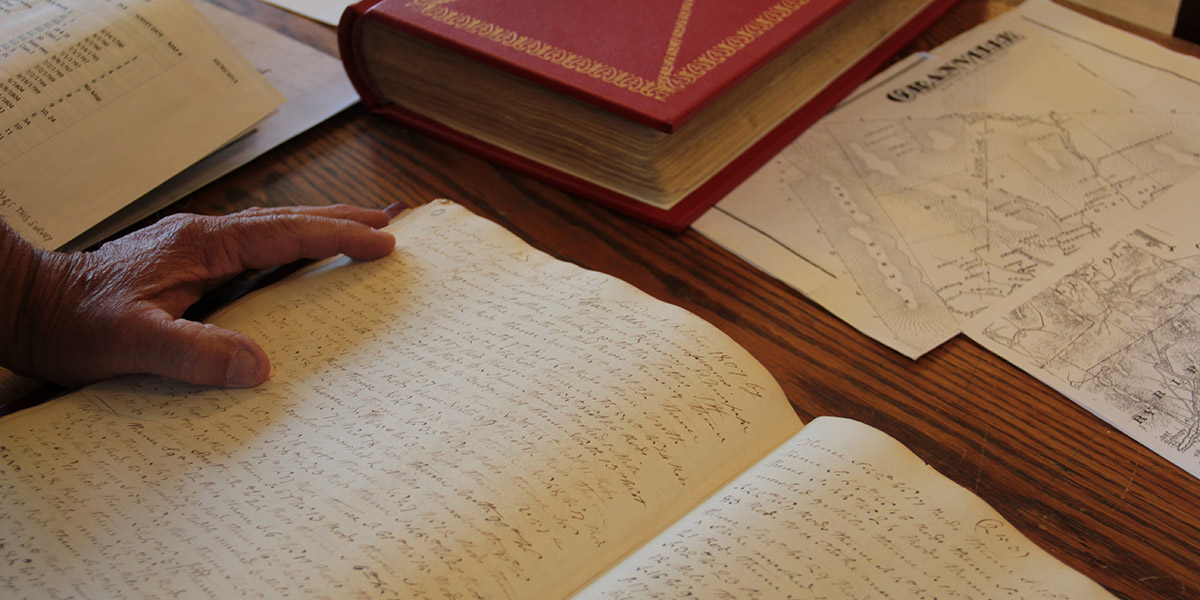

[Image: Reviewing old property deeds and land surveys; photo by Geoff Manaugh].

[Image: Reviewing old property deeds and land surveys; photo by Geoff Manaugh].

A story I’ve been obsessed with since first learning about it back in 2008 is the problem of “ancient roads” in Vermont.

Vermont is unusual in that, if a road has been officially surveyed and, thus, added to town record books—even if that road was never physically constructed—it will remain legally recognized unless it has been explicitly discontinued.

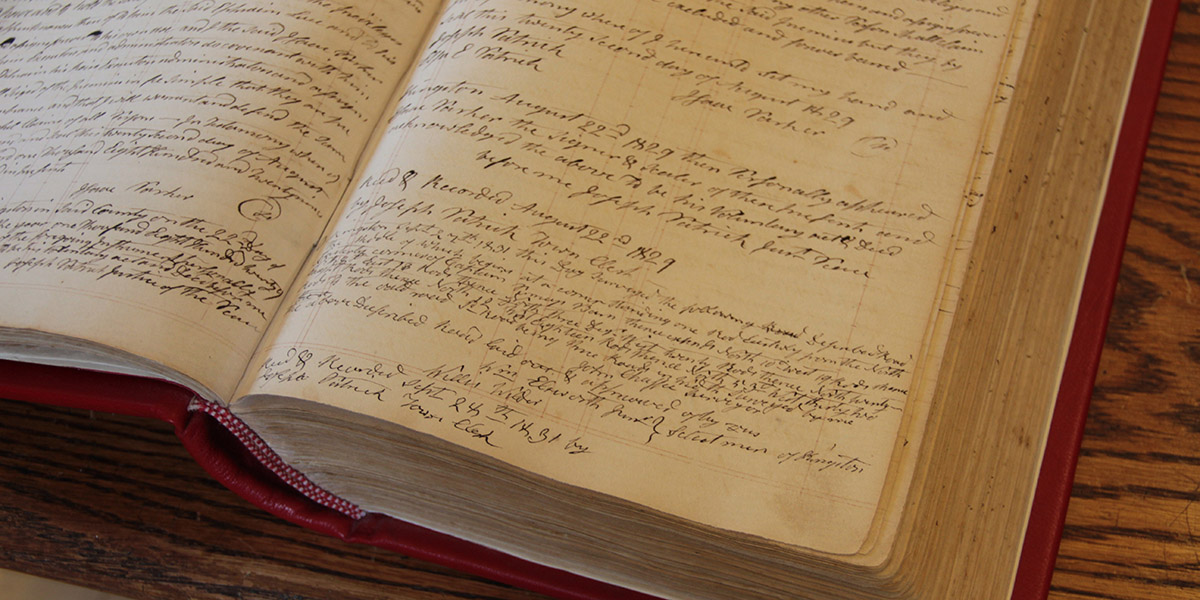

[Image: More Granville property deeds; photo by Geoff Manaugh].

[Image: More Granville property deeds; photo by Geoff Manaugh].

This means that roads surveyed as far back as the 1790s remain present in the landscape as legal rights of way—with the effect that, even if you cannot see this ancient road cutting across your property, it nonetheless persists, undercutting your claims to private ownership (the public, after all, has the right to use the road) and making it difficult, if not impossible, to obtain title insurance.

Faced with a rising number of legal disputes from homeowners, Vermont passed Act 178 back in 2006. Act 178 was the state’s attempt to scrub Vermont’s geography of these dead roads.

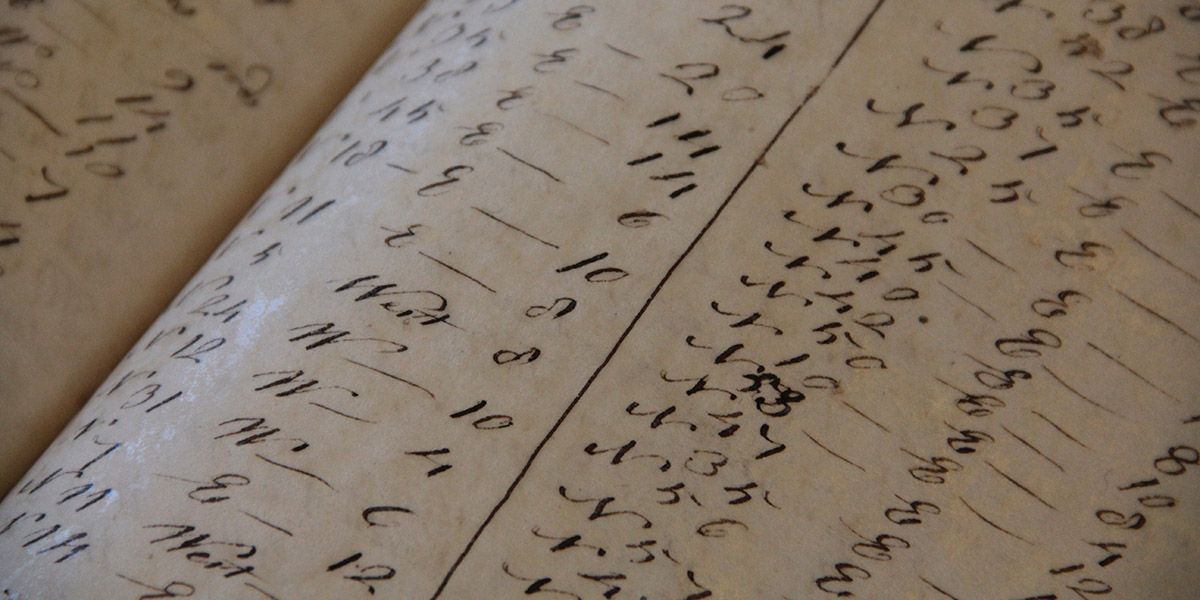

[Image: Geographic coordinates for lost roadways; photo by Geoff Manaugh].

[Image: Geographic coordinates for lost roadways; photo by Geoff Manaugh].

The Act’s immediate effects, however, were to kick off a rush of new research into the state’s lost roadways.

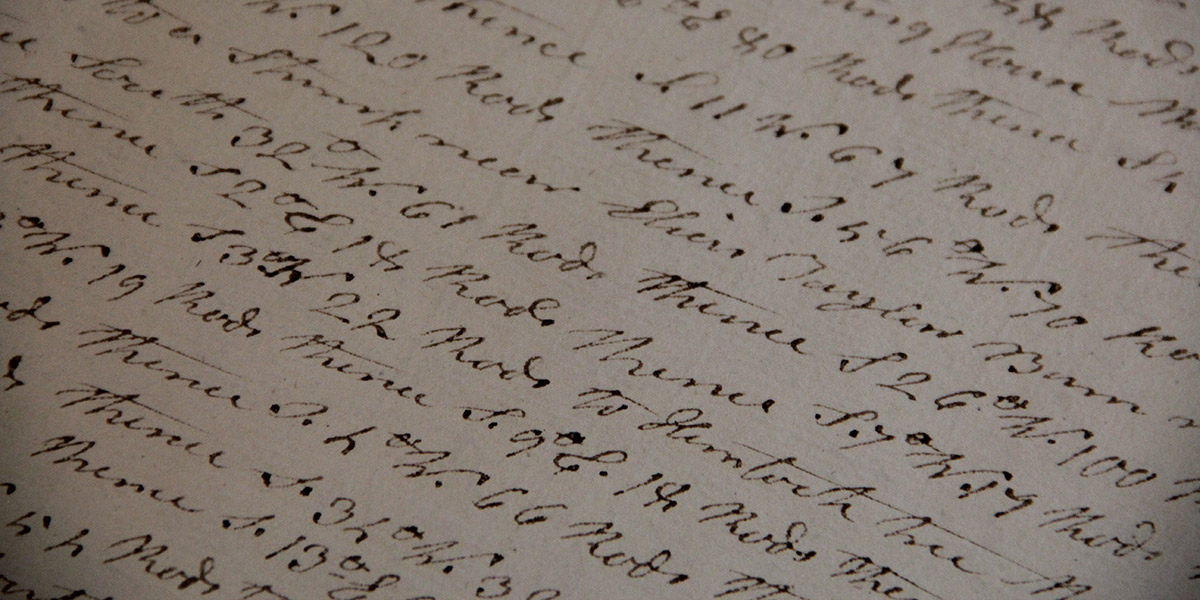

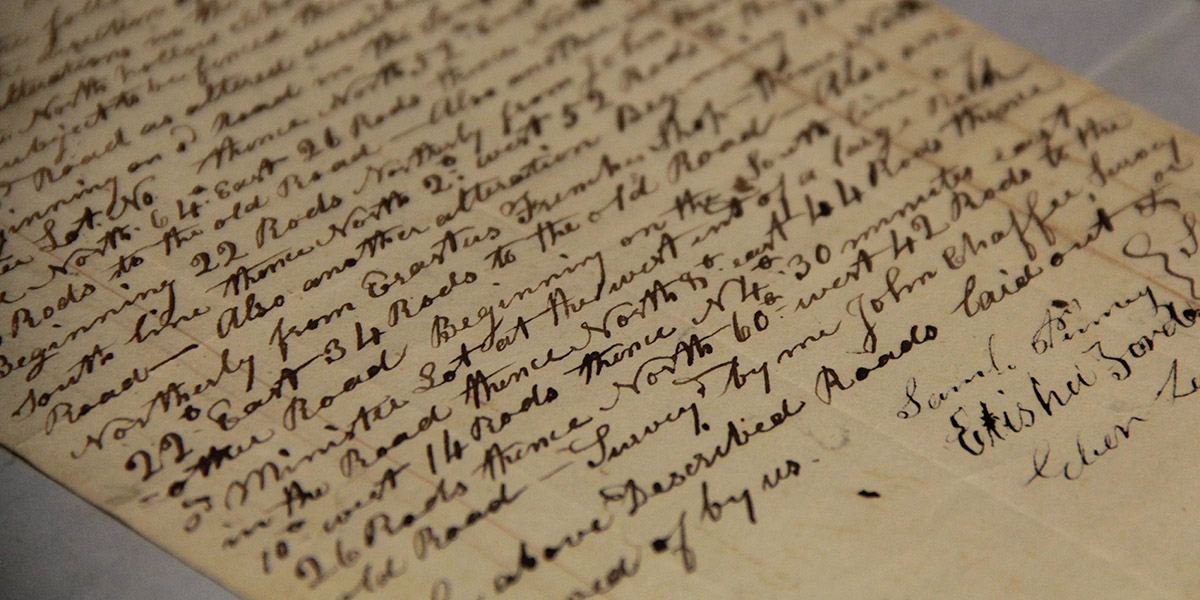

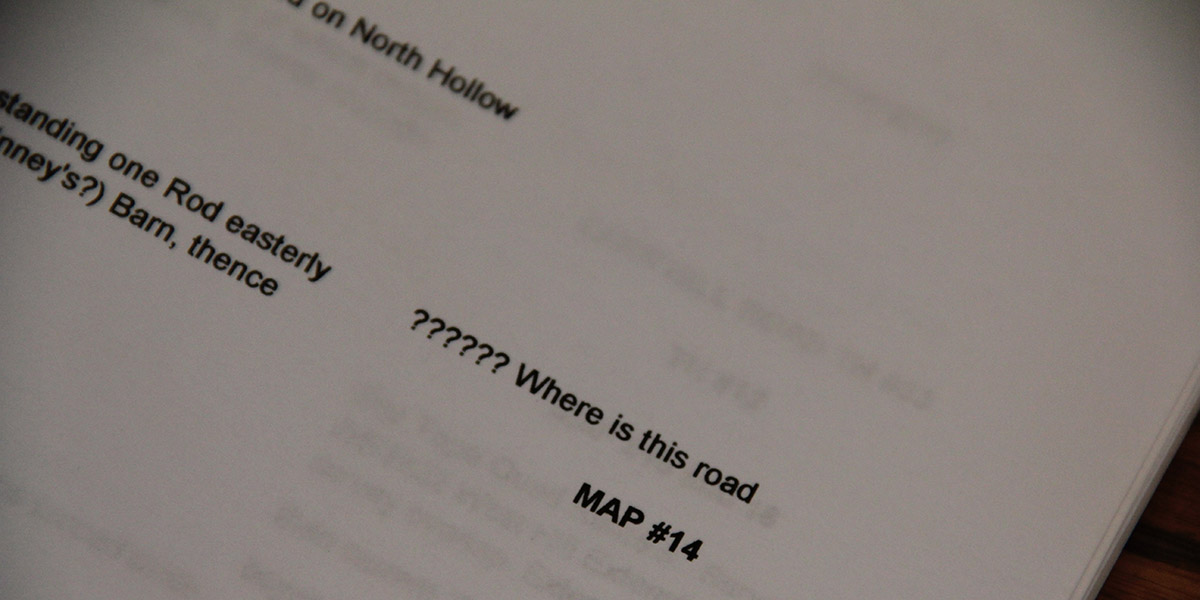

This meant going back through property deeds and mortgage records, dating back to the late 18th-century, deciphering old handwriting, making sense of otherwise location-less survey coordinates, and then reconciling all this with on-the-ground geologic features or local landmarks.

[Image: Zooming into survey descriptions of rods and chains; photo by Geoff Manaugh].

[Image: Zooming into survey descriptions of rods and chains; photo by Geoff Manaugh].

Not every town was enthusiastic about finding them, hoping instead that the old roads would simply disappear.

Other towns—and specific townspeople—responded with far more enthusiasm, as if finding an excuse to rediscover their own histories, the region’s past, and the lives of the other families or settlers who once lived there.

Anything they found and officially submitted for inclusion on Vermont’s state highway map would continue to exist as a state-recognized throughway; anything left undocumented, or specifically called out for discontinuance, would disappear, losings its status as a road and becoming mere landscape.

July 1, 2015, was the deadline, after which anything left undiscovered is meant to remain undiscovered.

[Image: Ancient road descriptions; photo by Geoff Manaugh].

[Image: Ancient road descriptions; photo by Geoff Manaugh].

I had an amazing opportunity to visit the tiny town of Granville, Vermont, ten days ago, where I met with a retired forester and self-enlisted local historian named Norman Arseneault.

Arseneault became so involved in the search for Granville’s ancient roads that he is not only self-publishing an entire book documenting his quest, but he was also pointed out to me as an exemplar of rigor and organization by Johnathan Croft, chief of the Mapping Section at the Vermont Agency of Transportation (where there is an entire page dedicated to “Ancient Roads“).

His hunt for old roads seems to fall somewhere between Robert Macfarlane’s recent work and the old Western trail research of Glenn R. Scott.

[Image: “?????? Where is this road”; photo by Geoff Manaugh].

[Image: “?????? Where is this road”; photo by Geoff Manaugh].

While I was there in Granville, Arseneault took me into the town vault, flipping back through nearly 225 years of local property deeds. We then hit the old forest roads in his pick-up truck, to hike many of the “ancient roads” his research had uncovered.

I wrote up the whole experience for The New Yorker, and I have to say it was one of the more interesting article research processes I’ve ever been involved with; check it out, if any of this sounds of interest.

It’s worth pointing out, meanwhile, that the problem of “ancient roads” is not, in fact, likely to go away; the recent introduction of LiDAR data, on top of some confusingly written legal addenda, make it all but certain that other property owners will yet find long-forgotten public routes crossing their land, or that a future private development count still find its unbuilt plots placed squarely atop invisible roads made newly available to town use.

The hows and whys of this are, I hope, explained a bit more over at The New Yorker.

In Belgium the "Atlas van de Buurtwegen" dates back to 1841. (example of a province). This document still has force of law and even very recently a house technically had to be torn down because it was built on a forgotten footpath.

Not just LiDAR can help with this search, but Foliage Penetrating Radar has provided great assistance with archaeological work like this.