[Image: A parking spiral, originally published in Concrete Quarterly, as documented by The Sesquipedalist].

[Image: A parking spiral, originally published in Concrete Quarterly, as documented by The Sesquipedalist].

Category: BLDGBLOG

A Traffic Jam is a Collection of Rooms

[Images: The micro-culture of the motorway; images courtesy Associated Press/Wall Street Journal].

[Images: The micro-culture of the motorway; images courtesy Associated Press/Wall Street Journal].

It was hard to miss the story last month that a 62-mile long traffic jam had formed in China, becoming a near-permanent feature of that nation’s roadway system. It lasted nine full days, in a state of almost perfect gridlock. NPR reported that drivers simply turned off their cars and slept for 8 hours at a time.

A temporary micro-culture of the motorway soon emerged: “Villagers along Highway 110 took advantage of the jam,” the Wall Street Journal reported, “selling drivers packets of instant noodles from roadside stands and, when traffic was at a standstill, moving between trucks and cars to hawk their wares. Truck drivers, when they weren’t complaining about the vendors overcharging for the food, kept busy playing card games.”

[Images: The traffic jam as scene from Dante; images courtesy Associated Press/Wall Street Journal].

[Images: The traffic jam as scene from Dante; images courtesy Associated Press/Wall Street Journal].

But what if another such traffic jam were to form again? Where role might there be for architecture? Clip-on awnings, zip-up tent walls, velcro-connected halls and corridors spanning car-to-car and truck door to truck door, even crawlable tunnels for kids, with mobile parks on flatbed trucks, whole canopies held down by duct tape, antennas repurposed as anchors for tarps and makeshift roofs. Outdoor cinemas are formed. Social cliques develop.

The spatial infrastructure of the permanent traffic jam kicks in: guerrilla, unfoldable, pack-into-a-backpack-able, made from lightweight materials—ripstop fabrics and military-grade rope—a city takes shape on the highway, with every car, bus, truck, and motorcycle a luxury room or repurposed piece of home furniture.

[Image: Courtesy of Newscom and the Christian Science Monitor].

[Image: Courtesy of Newscom and the Christian Science Monitor].

Lock this in place a few years and give it a postcode. Children are born there. Like Dan Hill‘s quip that “There are 500000 people airborne at any one time. A drifting airborne city, the size of Helsinki, a few meters tall, threaded around [the] globe,” this city-on-the-road would be named, memorialized, revisited. New highways would simply thread around it, abandoning the vehicles to their stationary fate as their tires drain of air and engines stall forever.

Generations later, the fact that, down in the mud and dust beneath your metropolis, you can find abandoned frames and chassis from the city’s founding traffic jam, will be impossible to believe—a run-of-the-mill urban legend. Archaeologists will argue over the best sites to excavate to find truck doors and ancient oil spills down there in the formerly mobile foundations of the city.

Even David Greene of Archigram once wrote that “a traffic jam is a collection of rooms.”

[Image: From Archigram].

[Image: From Archigram].

“We also know that a traffic jam is a collection of rooms,” Greene wrote in a short text called “Gardener’s notebook,” and “so is a car park—they are really instantly formed and constantly changing communities. A drive-in restaurant ceases to exist when the cars are gone (except for cooking hardware). A motorized environment is a collection of service points.”

On the level of architecture, then, what could we do to prepare for the impending return of the near-permanent Chinese traffic jam? What prosthetic walls, floors, ceilings, and corridors—what new families of clip-on architectural forms—could we explore?

Traffic Walls™—an instant city brought to you by North Face and the GA Tech School of Architecture. Easily deployed. Houses up to 10,000 people. Machine-washable.

Of networked buildings and architectural neurology

[Image: A glimpse of Honda’s brain-interface technology].

[Image: A glimpse of Honda’s brain-interface technology].

I thought I’d jump into the ongoing conversation swirling around Tim Maly’s Cyborg Month—of which you can read more here—with some loose thoughts about what an architectural cyborg might be.

There have already been some significant stabs made in this direction over the past few weeks, including a brief look at “architecture machines”—that is, “evolving systems that worked in ‘symbiosis’ with designer and resident,” promising to “turn the design process into a dialogue that would alter the traditional human-machine dynamic” and thus opening up the possibility of cyborg architecture.

But my interests here are both more speculative and more neurological—specifically, looking at the wiring together of buildings and nervous systems, and the strange possibilities that might result. As such, I’ll be revisiting/rewriting some older posts here, tailoring them specifically for the context of Maly’s Cyborg Month.

[Image: Earthly extensions crawl on Mars; courtesy of NASA/JPL-Caltech].

[Image: Earthly extensions crawl on Mars; courtesy of NASA/JPL-Caltech].

1) A few years ago, two unrelated bits of news accidentally merged for me, their headlines crossing to surreal effect. First, we learned that monkeys were able to move a robotic arm “merely by thinking.” The arm, which included “working shoulder and elbow joints and a clawlike ‘hand’,” was controllable after “probes the width of a human hair were inserted into the neuronal pathways of the monkeys’ motor cortex.” This field of research is referred to as “mind-controlled robotic prosthetics”—but the mind in control here is not human.

Second, the New York Times reported that “NASA’s Phoenix Mars lander has successfully lifted its robotic arm” up there on the surface of another planet. “Testing the arm will take a few days,” we read, “and the first scoops of Martian soil are to be dug up next week.”

And while I know that these stories are in no way connected, putting them together is like something from the pages of Mike Mignola: monkeys locked in a room somewhere, controlling the arms of machines on other planets.

As if we might discover, at the end of the day, that NASA wasn’t a human organization at all—it was a bunch of rhesus monkeys locked in a lab somewhere, enthroned amidst wires and brain-caps, like some new sign of the Tarot, lost in private visions of machines on alien worlds. An experiment gone awry.

Their “dreams” at night are actually video feeds from probes moving through outer darkness.

[Image: A “Demon” unmanned aerial drone by BAE Systems, courtesy of Popular Science].

[Image: A “Demon” unmanned aerial drone by BAE Systems, courtesy of Popular Science].

2) Among many other things in P.W. Singer’s highly recommended book Wired for War: The Robotics Revolution and Conflict in the Twenty-First Century is a brief comment about military research into the treatment of paralysis.

In a subsection called “All Jacked Up,” Singer refers to “a young man from South Weymouth, Massachusetts,” who was “paralyzed from the neck down in 2001.” After nearly giving up hope for recovery, “a computer chip was implanted into his head.”

The goal was to isolate the signals leaving [his] brain whenever he thought about moving his arms or legs, even if the pathways to those limbs were now broken. The hope was that [his] intent to move could be enough; his brain’s signals could be captured and translated into a computer’s software code.

The man’s doctors thus hook him up to a computer mouse and then to a TV remote control, and the wounded man was soon able not only to surf the web but to watch HBO.

What I can’t stop thinking about, however, is where this research “opens up some wild new possibilities for war,” as Singer writes.

In other words, the military has asked, why hook this guy up to a remote control TV when you could hook him up to an armed drone aircraft flying somewhere above Afghanistan? The soldier could simply pilot the plane with his thoughts.

This vision—of paralyzed soldiers thinking unmanned planes through distant theaters of war—is both terrible and stunning.

Singer goes on to describe DARPA‘s “Brain-Interface Project,” which hoped to teach paralyzed patients how to control machines via thought—and to do so in the service of the U.S. military.

Later in the book, Singer describes research into advanced, often robotic prostheses; “these devices are also being wired directly into the patient’s nerves,” he writes.

This allows the solder to control their artificial limbs via thought as well as have signals wired back into their peripheral nervous system. Their limbs might be robotic, but they can “feel” a temperature change or vibration.

When this is put into the context of the rest of Singer’s book—where we read, for instance, that “at least 45 percent of [the U.S. Air Force’s] future large bomber fleet [will be] able to operate without humans aboard,” with other “long-endurance” military drones soon “able to stay aloft for as long as five years,” and if you consider that, as Singer writes, the Los Angeles Police Department “is already planning to use drones that would circle over certain high-crime neighborhoods, recording all that happens”—you get into some very heady terrain, indeed. After all, the idea that those drone aircraft circling over Los Angeles in the year 2015 are actually someone’s else literal daydream both terrifies and blows me away.

On the other hand, if you can directly link the brain of a paralyzed soldier to a computer mouse—and then onward to a drone aircraft, and perhaps onward again to an entire fleet of armed drones circling over enemy territory—then surely you could also hook that brain up to, say, lawnmowers, remote-controlled tunneling machines, lunar landing modules, Mars rovers, strip-mining equipment, woodworking tools, and even 3D printers.

[Image: 3D printing, via Thinglab].

[Image: 3D printing, via Thinglab].

The idea of brain-controlled wireless digging machines, in particular, just astonishes me; at night you dream of tunnels—because you are actually in control of tunneling equipment as you sleep, operating somewhere beneath the surface of the planet.

A South African platinum mine begins to diverge wildly from known sites of mineral wealth, its excavations more and more abstract as time goes on—carving M.C. Escher-like knots and strange excursive whorls through ancient reefwork below ground—and it’s because the mining engineer, paralyzed in a car accident ten years ago and in control of the digging machines ever since, has become addicted to morphine.

Or perhaps this could even be used as a new and extremely avant-garde form of psychotherapy. For instance, a billionaire in Los Angeles hooks his depressed teenage son up to Herrenknecht tunneling equipment which has been shipped, at fantastic expense, to Antarctica. An unmappably complex labyrinth of subterranean voids is soon created; the boy literally acts out through tunnels. If rock is his paint, he is its Basquiat.

Instead of performing more traditional forms of Freudian analysis by interviewing the boy in person, a team of highly-specialized dream researchers is instead sent down into those artificial caverns, wearing North Face jackets and thick gloves, where they deduce human psychology from moments of curvature and angle of descent.

My dreams were a series of tunnels through Antarctica, the boy’s future headstone reads.

[Image: The hieroglyphic end of a Canadian potash mine; courtesy of AP/The Australian].

[Image: The hieroglyphic end of a Canadian potash mine; courtesy of AP/The Australian].

Returning to Singer, briefly, he writes that “Many robots are actually just vehicles that have been converted into unmanned systems”—so if we can robotize aircraft, digging machines, riding lawnmowers, and even heavy construction equipment, and if we can also directly interface the human brain to the controls of these now wireless robotic mechanisms, then the design possibilities seem limitless, surreal, and well worth exploring (albeit with great moral caution) in real life.

3) What, then, in this context, might an architectural cyborg be? While it’s tempting to outline a number of scenarios in which a human brain could be directly wired into, say, the elevator control room of a downtown high-rise, or into the traffic lights of a Chinese metropolis, this scenario could also be disturbingly reversed.

In other words, why have a building somehow controlled by a human brain, when a human brain could instead be controlled by a building?

Like something out of Michael Crichton’s Coma—or even the film Hannibal (NSFW and highly disturbing!)—future elevator banks in New York’s replacement World Trade Center cause wireless twitching in an otherwise bed-bound patient. That is, the patient moves because of the elevators, and not the other way around.

Imagine a zombie horror film, complete with stumbling hordes guided not by demonic hunger but by the malfunctioning HVAC system of a building outside town…

[Image: A circuit diagram].

[Image: A circuit diagram].

At this point, though, I’d rather step back from these morally uncomfortable images and suggest instead that buildings connected to other buildings might form their own ersatz neurology: like the hacked brain of a military paralytic, one building’s elevators would actually control the elevators in another building.

Networked examples of this are easy enough to invent: the computer system of one building is cross-wired into the circuitous guts of another structure, be it a skyscraper, an airplane, a geostationary satellite, a moving truck, or an interstellar probe built by NASA (and why stop at buildings—why not networked plants?). The changing speeds of a building’s escalators become more like graphs: responding to—and thus diagramming—signals from a rover on Mars.

They are pieces of equipment, we might say, neurologically interfering with one another.

In many ways, this just takes us back to the cybernetic designs mentioned earlier, but it also leads to a general question: are two buildings hooked up to each other, in the most intimate ways, their HVACs purring in perfect co-harmony, responding to and controlling one another, each incomplete without its cross-wired partner, actually cyborgs?

For more posts in Tim Maly’s ongoing series, check out 50 Posts About Cyborgs.

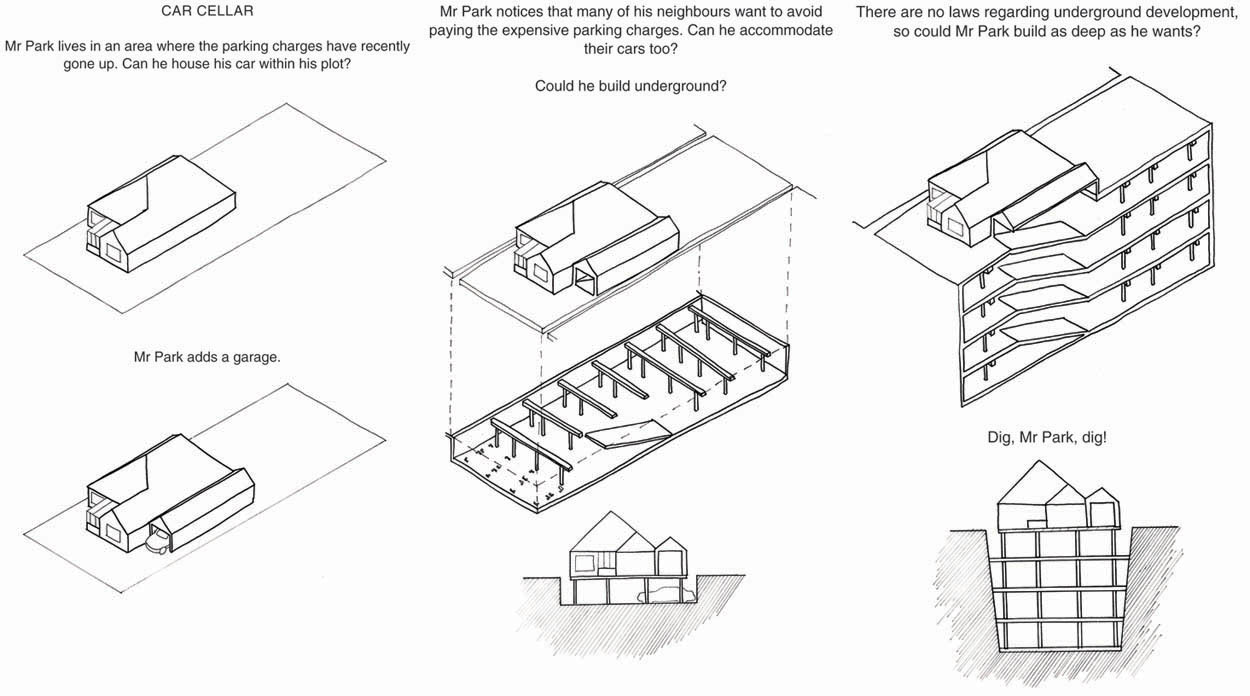

The Permission We Already Have

[Image: Courtesy of David Knight and Finn Williams].

[Image: Courtesy of David Knight and Finn Williams].

David Knight and Finn Williams have been investigating what they call “minor development” in the field of architecture and urban planning for several years now, and their discoveries are absolutely fascinating. Last year they published a book called SUB-PLAN: A Guide to Permitted Development, exploring the world of building extensions, temporary structures, outdoor spaces, and other minor acts of home construction that fly beneath the radar of official town planning.

“How far does planning control what we build? And what can we build without planning?” the authors ask. “SUB-PLAN explores the legal possibilities of building outside the limits of legislation.”

The UK planning system has been swamped by minor applications for household extensions and outbuildings that cause a backlog of bureaucracy and dominate the limited resources of local planning authorities. On 1 October 2008 the government introduced changes to the General Permitted Development Order 2 to reduce the number of minor applications by expanding the definition of what can be built without planning permission.

But, they add, “are the implications of minor development more significant than planners imagine?”

[Images: Courtesy of David Knight and Finn Williams].

[Images: Courtesy of David Knight and Finn Williams].

Knight and Williams will be participating in a public conversation next week in London, sponsored by the Architecture Foundation; called Permitted Development: The Planning Permission We Already Have, it will be an example of what we might call legislative forensics, looking into the law books—and the urban planning guidelines—to see what architectural possibilities already exist in the present day for residents to explore.

In that previous sentence, I almost wrote “for residents and homeowners to explore”—but I wonder if you really need to be a homeowner to take advantage of these unpublicized zones of building permission? Is simply being a citizen enough, or must you own property to participate in the realm of minor architecture? Or is there even an unacknowledged world of building practices legally open to construction by non-citizens—by people who, legally speaking, reside nowhere?

In the intersection between architecture and permission, what spaces are possible and who has the right to realize them? What are the possibilities for architectural insurrection—or, at the very least, aesthetic experimentation?

[Image: An awesome glimpse of “the permission we already have,” courtesy of SUB-PLAN by David Knight and Finn Williams; view larger].

[Image: An awesome glimpse of “the permission we already have,” courtesy of SUB-PLAN by David Knight and Finn Williams; view larger].

In Sweden, for instance, there is a type of small garden shed known as the friggebod, named after Birgit Friggebo, Sweden’s former housing minister. “The term is a wordplay based on the common term bod: (tool) shed; shack,” Wiktionary explains. “The friggebod reform implied that anyone could build a shed of maximum 10 square meters on their premises without obtaining a construction permit from the municipality. In Sweden, the reform became a widely popular symbol of liberalization. From the onset of 2008, the area was increased to 15 square meters.”

These autonomous planning zones, so to speak, open up architectural production to non-architects in a possibly quite radical way. So how do we take advantage of them?

[Images: Another mind-bending example of “the permission we already have,” courtesy of SUB-PLAN by David Knight and Finn Williams].

[Images: Another mind-bending example of “the permission we already have,” courtesy of SUB-PLAN by David Knight and Finn Williams].

Next week’s event in London bills itself as follows:

Though apparently at the humble end of the planning system, recent changes to Permitted Development rights are a treasure trove of architectural potential. The new breed of lean-tos, loft conversions, sheds and summerhouses they allow could have far-reaching and surprising consequences for UK towns and countryside. Finn Williams and David Knight will present recent projects which explore and exploit Permitted Development rules.

I’d love to hear how this goes, in case anyone there can report back. To be honest, I think this type of research is both jaw-dropping and urgently needed elsewhere. What unknown architectural permissions exist for the residents of Manhattan, LA, Beijing, São Paulo…?

What future DIY architectures have yet to arise around us—and when will we set about constructing them?

Geometric Sociology

[Image: A prison in the desert soutwest; photo by, and courtesy of, Christoph Gielen].

[Image: A prison in the desert soutwest; photo by, and courtesy of, Christoph Gielen].

I’ve got a short text in the New York Times this weekend about the aerial photographs of Christoph Gielen. His photos feature both prison complexes and retirement communities, shot from above via helicopter, in the desert southwest.

The geometries formed by these buildings and streets—boxes, whorls, circles, half-labyrinths, and interrupted circuitboards—give the sites a remarkable visual footprint. One of the developments has even become a unique aerial landmark for passing airplanes. A settled world that perhaps only makes sense from above.

The text itself starts off with a long quotation from Thomas Pynchon’s The Crying of Lot 49—but I’m indebted to architect Ed Keller for reminding me of that passage.

So check it out! And check out Gielen’s other work when you get a chance, as well.

LAX–ATL

[Images: Masonry beehives discovered in Scotland’s Rosslyn Chapel; photos courtesy of the Times. The “architecture of beehives,” from François Huber’s Nouvelles observations sur les abeilles, courtesy of Cabinet Magazine].

[Images: Masonry beehives discovered in Scotland’s Rosslyn Chapel; photos courtesy of the Times. The “architecture of beehives,” from François Huber’s Nouvelles observations sur les abeilles, courtesy of Cabinet Magazine].

For those of you in the Atlanta area, Nicola Twilley of Edible Geography and I will be presenting our blogs, our collaborative work, and our own solo projects at the Georgia Tech College of Architecture tomorrow night, Wednesday, September 15th.

Expect to hear about everything from the Foodprint Project to Landscapes of Quarantine, from sewer divers in Mexico City to the Mole Man of Hackney, and from a forthcoming exhibition at the Nevada Museum of Art called Landscape Futures to the 3D-printing potential of silkworms and bees. We’ll be in the Reinsch-Pierce Family Auditorium at Georgia Tech, kicking off at 6pm. It’s free and open to the public.

White Sun

[Image: “How to photograph an atomic bomb,” via the New York Times].

[Image: “How to photograph an atomic bomb,” via the New York Times].

The New York Times is featuring a powerful series of photographs documenting the work of a “secret corps” of “atomic moviemakers.”

Electrified wire ringed their headquarters in the Hollywood Hills. The inconspicuous building, on Wonderland Avenue in Laurel Canyon, had a sound stage, screening rooms, processing labs, animation gear, film vaults and a staff of more than 250 producers, directors and cameramen—all with top-secret clearances.

This cinematographic brotherhood “focused on nuclear test explosions in the Pacific and Nevada,” though their work is only now being seen by the general public. “In all, the atomic moviemakers fashioned 6,500 secret films,” the New York Times reports.

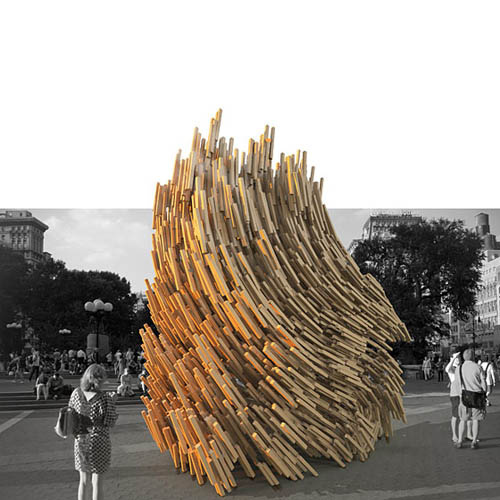

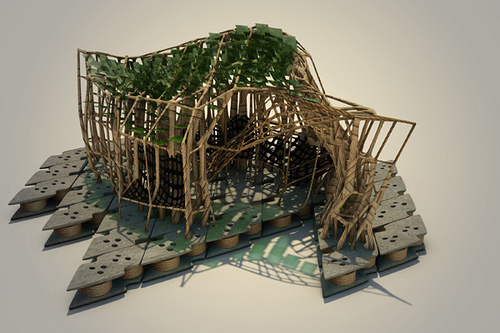

Sukkah City Approaches

[Image: The original graphic for Sukkah City].

[Image: The original graphic for Sukkah City].

All twelve winning designs for the Sukkah City competition have now been posted, along with an article in New York magazine giving an overview of what comes next. The actual construction of each of these temporary buildings is now underway, with all twelve soon to be standing in Manhattan’s Union Square.

The competition, as New York suggests, weds “religious tradition with architectural radicalism in the timely form of short-term shelter”—and the built results go up Sunday, September 19, through the evening of Monday, September 20.

[Image: P.YGROS.C—short for “Passive Hygroscopic Curls,” as if Autechre meets the Talmud—by THEVERYMANY of Brooklyn].

[Image: P.YGROS.C—short for “Passive Hygroscopic Curls,” as if Autechre meets the Talmud—by THEVERYMANY of Brooklyn].

I’ve included images of just four of those finalists—but, with 600 entries coming in from 43 countries, the full extent of the competition is well worth checking out over at the contest website.

[Image: Gathering by Dale Suttle, So Sugita, and Ginna Nguyen of New York City].

[Image: Gathering by Dale Suttle, So Sugita, and Ginna Nguyen of New York City].

It’s also worth recalling the actual design guidelines, which are taken straight from rabbinical interpretations of the original sukkah form and explain many of the formal gestures you see here.

New York points out a few specifics from this “thicket of rules”:

The Talmud demands that a sukkah have at least two and a half walls, a roof that allows indwellers to see the stars and feel the rain but nevertheless stay mostly in the shade. The roof must be made of uprooted organic material—twigs or fronds, say—but no food or utensils (no chopstick thatching allowed). Mystifyingly, the rabbis of yore explicitly permitted the carcass of an elephant to be used as one of the walls. (No contestants took advantage of that option, sensing perhaps that the Department of Buildings or PETA might not concur.)

These rules have been “accumulated as a historiographical record of debates and distinctions developed by generations of scholars and theologians, that, taken together, read like something between a civic zoning code and a beat prose poem,” as competition juror Thomas de Monchaux writes in a long piece for Design Observer.

[Images: (top) Fractured Bubble by Henry Grosman and Babak Bryan of Long Island City; (bottom) Shim Sukkah by tinder, tinker of Sagle, Idaho].

[Images: (top) Fractured Bubble by Henry Grosman and Babak Bryan of Long Island City; (bottom) Shim Sukkah by tinder, tinker of Sagle, Idaho].

Diving into the architectural mythology of the sukkah, de Monchaux shows how the almost whimsically restrictive limits of what constitutes a sukkah open up a hugely various, dynamic, and complex space for contemporary design.

And there are some great designs in there; one of my favorites—which turned out to have been co-designed by one of my former students at Columbia—didn’t make the final cut, but seems worth reproducing here: a sukkah held together through a superstructure of rope that then spools back down through the portable foundations of the sukkah itself, like some geometric cross between the terrestrial and the maritime. Where masts are walls, and the floor is the deck of a grounded vessel.

[Image: XNOT by Morgan Reynolds, Ravi Raj, and John Becker of New York City].

[Image: XNOT by Morgan Reynolds, Ravi Raj, and John Becker of New York City].

Regrettably, I will not be in NYC to see the actual installation, but I eagerly await seeing photos and videos of the results. Feel free to leave comments here, or to email me, with images.

And congratulations to the twelve finalists! It was an exciting competition, stimulating a huge range of reactions to almost every single project, and I was thrilled to be part of the judging process.

Finally, vote for the “People’s Choice Sukkah” over at New York magazine.

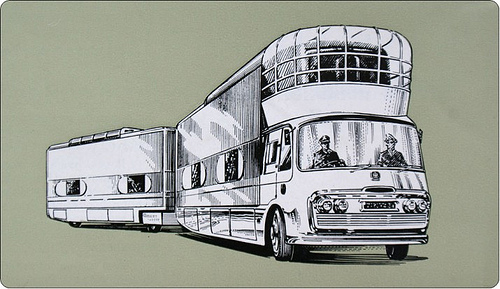

Vintage Mobile Cinema

[Image: The Vintage Mobile Cinema].

[Image: The Vintage Mobile Cinema].

This is great: a fully restored mobile cinema that’s been traveling the rural roads of Devon, England, since the beginning of the summer.

“A rare 1967 mobile cinema is being restored in North Devon,” the North Devon Gazette reported last year, “and will visit schools and communities across the county next year, showing historic films unseen for many years, including old footage of the area.”

[Image: One of the originally commissioned vans].

[Image: One of the originally commissioned vans].

Seven of these vans were originally commissioned by the UK’s Ministry of Technology; this one, a Bedford SB3, “is the only one of the original mobile cinemas to have survived. It was rescued by a previous owner after sitting in a field for 14 years.”

The ensuing restoration was performed by local Devonian Oliver Halls and a group of his friends.

[Images: Mobile cinemas commissioned by the UK Ministry of Technology].

[Images: Mobile cinemas commissioned by the UK Ministry of Technology].

If you’re in England now and hoping to check out a screening, you’ll find a schedule here, along with brief descriptions of some of the featured films.

It should not be a surprise to learn that the van has also got a Facebook page.

[Images: The Vintage Mobile Cinema].

[Images: The Vintage Mobile Cinema].

The interior itself is the cinema, meanwhile; you actually sit inside the van and watch films from the comfort of one of its 22 upholstered seats. The equipment, as listed by the blog Home Cinema Choice, includes:

Onkyo TX-NR807 receiver

Pioneer BDP-320 Blu-ray player

Mordaunt Short Aviano 6 floorstander speakers

Mordaunt Short Alumni 9 subwoofer speaker

Mordaunt Short Alumni 5 center speaker

Mordaunt Short Alumni 3 surround speakers (x4)

Epson EH-TW3500 LCD projector

The seats themselves date from the 1930s.

[Image: Inside the Vintage Mobile Cinema].

[Image: Inside the Vintage Mobile Cinema].

As you can see on the van’s Facebook page, the renovation process was both extensive and very impressive—the vehicle went from a genuine wreck to road-ready. It took more than just a quick coat of paint.

[Images: The van, awaiting renovation].

[Images: The van, awaiting renovation].

Here are some shots of other vans from the original commission, as archived by the Vintage Mobile Cinema project. These have all since disappeared, presumably sold and scrapped, pushing the whole lineage nearly to extinction. Or perhaps another one will pop up someday, found in an old barn somewhere out in Cornwall.

[Images: Vintage photos of the original cinema van series].

[Images: Vintage photos of the original cinema van series].

It’s such a cool vehicle, and an amazing project: bringing films to places where public cinema might not normally reach.

Even cooler, if you’re a filmmaker, you can actually see your work screened inside this thing:

We are looking for independent film-makers work at the moment, to screen aboard the Vintage Mobile Cinema as we tour different events across the country. This is an opportunity for film-makers to have their work screened in a unique environment; a one-of-a-kind 1967 Mobile Cinema, the last survivor from a fleet of seven. The vehicle is completely unique, featuring a retro-futuristic perspex dome above the cab, and it causes heads to turn whereever it goes!

While the call-for-films specifically referred to a festival that occurred at the end of August, it seems you still have a chance; there’s contact info, in case you want to inquire.

[Image: Graphics for the cinema van].

[Image: Graphics for the cinema van].

All in all, the renovation looks superb and this particular example of flexible infrastructure—the cinema gone mobile—is an inspiring one. Perhaps this might even qualify as a soft system, in the context of Bracket 2.

Mash House

[Image: Mash House by Andrew Maynard Architects; photo by Kevin Hui].

[Image: Mash House by Andrew Maynard Architects; photo by Kevin Hui].

The Mash House by Andrew Maynard Architects has taken shape on its site in Australia, and, minus a forthcoming regrowth of the immediate landscape, it looks great.

[Images: Mash House by Andrew Maynard Architects; photos by Kevin Hui].

[Images: Mash House by Andrew Maynard Architects; photos by Kevin Hui].

It’s more like a wooden object extruded from an industrial design seminar than what you might expect from a suburban home, and it’s also gloriously retro-colorful on the inside, with a lime green kitchen and pixellated red tiles in the bathroom.

Here are some photos.

[Images: Mash House by Andrew Maynard Architects; photos by Kevin Hui].

[Images: Mash House by Andrew Maynard Architects; photos by Kevin Hui].

The interior, as I mentioned, is a very Dwell-friendly throwback, complete with seamless expanses of color, rounded edges, sliding glass walls, and retro furnishings (brought in by the homeowners).

Very little project text is available online at the moment, however, so I’m basically just describing these photographs; I’m sure you can see for yourself how the interior has been styled.

[Images: Mash House by Andrew Maynard Architects; photos by Kevin Hui].

[Images: Mash House by Andrew Maynard Architects; photos by Kevin Hui].

And here are two shots of the bathroom, red tiles included.

[Images: Mash House by Andrew Maynard Architects; photos by Kevin Hui].

[Images: Mash House by Andrew Maynard Architects; photos by Kevin Hui].

Finally, these process-shots taken during construction show the house in a bit more of its context—which makes it look even more interesting as an experiment in suburban form.

[Images: Mash House by Andrew Maynard Architects; photos by Kevin Hui].

[Images: Mash House by Andrew Maynard Architects; photos by Kevin Hui].

I’d personally love to see more bookshelves—à la the Casa Kike or the interior of The Brain—but that’s probably only due to my own megaton collection of outdated paper-based texts…

See more at Andrew Maynard Architects.

Big Softy

Bracket 2 has been announced. This second issue of the annual design almanac seeks “critical articles and unpublished design projects that investigate physical and virtual soft systems, as they pertain to infrastructure, ecologies, landscapes, environments, and networks.”

[Image: Fabric urbanism: a “tent city,” via Bracket].

[Image: Fabric urbanism: a “tent city,” via Bracket].

If soft systems are, as the editors maintain, “a counterpoint to permanent, static and hard systems,” then what benefits do they bring, under what circumstances do they function best, and, of course, what do they look like (if they can be seen at all)?

While there is more information on Bracket‘s site, including some historical background on the emergence of soft systems in architectural planning and design, via figures such as Nicholas Negroponte and even Archigram, this issue of the journal is specifically looking for the following:

Bracket 2 seeks to critically position and define soft systems, in order to expand the scope and potential for new spatial networks, and new formats of architecture, urbanization and nature. From soft politics, soft power and soft spaces to fluid territories, software and soft programming, Bracket 2 questions the use and role of responsive, indeterminate, flexible, and immaterial systems in design. Bracket 2 invites designers, architects, theorists, ecologists, scientists, and landscape architects to position and leverage the role of soft systems and recuperate the development of the soft project.

For my own part, I’m increasingly interested in the design and implementation of what might be called soft medical infrastructure—or temporary, sometimes even inflatable, field hospitals and other on-demand medical facilities.

[Image: A “containerized” field hospital by the Red Cross and UN].

[Image: A “containerized” field hospital by the Red Cross and UN].

From a “modular air-transportable field camp” that has been “tested at the Arctic Circle” to first-responder architecture deployed on the scene of natural disasters, fires, acts of war, and terrorist attacks—and even by way of the somewhat ominous-sounding “systems for peacekeepers” devised by Kärcher Futuretech, down to the level of mobile catering units for use in remote landscapes and even inside warzones—how are architectural and infrastructural networks pushed into new design directions by extreme events?

[Image: Deployable Incident Command Post (ICP) by Reeves].

[Image: Deployable Incident Command Post (ICP) by Reeves].

Submissions are due before December 10, 2010, with a Fall 2011 publication date; the resulting book will be designed by Thumb and published by Actar.

Consider picking up a copy of Bracket 1: On Farming, meanwhile, to see how the journal works and what sorts of projects they might be looking for.