[Images: Two glimpses of “Museums of the City” by David Gissen (renderings by Victor Hadjikyriacou), commissioned by the Nevada Museum of Art for Landscape Futures: Instruments, Devices and Architectural Inventions; the title of this post comes from David Gissen].

[Images: Two glimpses of “Museums of the City” by David Gissen (renderings by Victor Hadjikyriacou), commissioned by the Nevada Museum of Art for Landscape Futures: Instruments, Devices and Architectural Inventions; the title of this post comes from David Gissen].

Category: BLDGBLOG

Layerscape

[Image: Milled terrain from “The Active Layer/Next North” by Lateral Office & InfraNet Lab, part of Landscape Futures: Instruments, Devices and Architectural Inventions at the Nevada Museum of Art].

[Image: Milled terrain from “The Active Layer/Next North” by Lateral Office & InfraNet Lab, part of Landscape Futures: Instruments, Devices and Architectural Inventions at the Nevada Museum of Art].

Island of Darwinian Machines

[Images: Liam Young constructs a robot Galapagos for “Specimens of Unnatural History,” part of Landscape Futures: Instruments, Devices and Architectural Inventions at the Nevada Museum of Art].

[Images: Liam Young constructs a robot Galapagos for “Specimens of Unnatural History,” part of Landscape Futures: Instruments, Devices and Architectural Inventions at the Nevada Museum of Art].

Switch

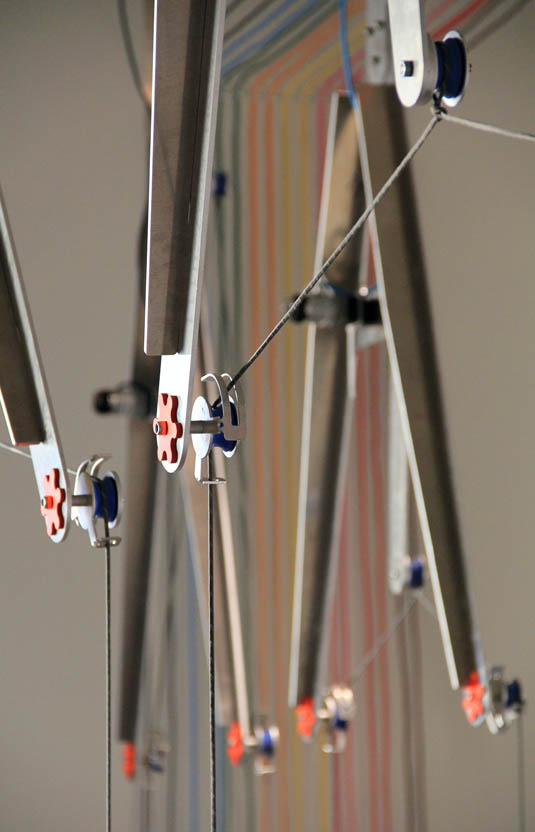

[Images: Marble run details from “Surface Tension” by Smout Allen, commissioned by the Nevada Museum of Art for Landscape Futures: Instruments, Devices and Architectural Inventions].

[Images: Marble run details from “Surface Tension” by Smout Allen, commissioned by the Nevada Museum of Art for Landscape Futures: Instruments, Devices and Architectural Inventions].

Installment Plan

[Image: A mechanical cloud of A-frames from “Surface Tension” by Smout Allen].

[Image: A mechanical cloud of A-frames from “Surface Tension” by Smout Allen].

I’ll be posting some photos taken last week during the installation process for Landscape Futures: Instruments, Devices and Architectural Inventions, at the Nevada Museum of Art in Reno. The exhibition opens this Saturday, August 13, and will be up until February 12, 2012.

[Image: Landscape Futures, “to be enlarged a lot”].

[Image: Landscape Futures, “to be enlarged a lot”].

These are photos I took myself, so they are not professional installation shots; but they should give at least some sense of how the exhibition is taking shape and what you can expect to see in the galleries. See forthcoming posts for more.

Landscape Futures is generously supported by the Graham Foundation for Advanced Studies in the Fine Arts, the Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts and the National Endowment for the Arts.

The New Robot Domesticity

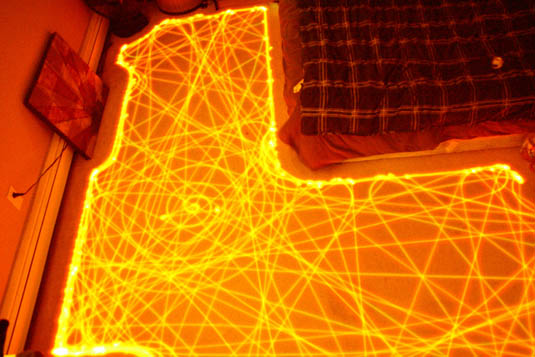

[Image: Optically tagged “robot-friendly bed sheets” from With Robots by Diego Trujillo-Pisanty].

[Image: Optically tagged “robot-friendly bed sheets” from With Robots by Diego Trujillo-Pisanty].

Diego Trujillo-Pisanty, currently a student in the Design Interactions department at the Royal College of Art in London, has looked ahead at how future homes might be redesigned to accommodate domestic robots.

Rather than build entire new forms of architecture, however, Diego suggests that we’ll first begin quite simply: retrofitting our interior environments, in often deceptively small ways, for optical navigation by autonomous mobile home systems. This will primarily take the form of peripheral additions to everyday objects, as well as a new range of optical tags that will allow certain tasks—folding blankets, for instance, or setting the dinner table—to be accomplished much easier by machines.

These tags will define both physical limits and the spatial operations appropriate within them, coding the everyday home environment for the rise of machine intelligence.

[Image: From With Robots by Diego Trujillo-Pisanty].

[Image: From With Robots by Diego Trujillo-Pisanty].

Homeowners will even help their robots learn through computational games—like Fröbel blocks for machines.

“Every living space is different,” the project description explains, “not only in the architectural layout, but also in the tasks that the tenants require robots to do. For this reason, robots ship only partially programmed so that through a learning algorithm they might adapt to the home they operate in. To accelerate the learning process, special learning tools have been designed to help the robot integrate to a 3D environment.” The photograph seen below “shows a living room after a robot self-training session. We can see it has now mastered the physics of equilibrium. It is also evident that it has mistaken one of the house’s dinner plates which it has broken with robotic precision to complete its piece.”

[Image: From With Robots by Diego Trujillo-Pisanty].

[Image: From With Robots by Diego Trujillo-Pisanty].

“Robot-friendly” handles will also be added to coffee mugs, the project suggests—which then ripples outward, effecting other spatial dimensions of the domestic environment, including where those mugs are stored. Thus, we read, “the cupboards in which these cups rest have also been altered in order to accommodate the robot. Not only are there tags marking the position of objects, but the doors have also been removed as they were not fit for A.I.”

[Image: From With Robots by Diego Trujillo-Pisanty].

[Image: From With Robots by Diego Trujillo-Pisanty].

Cooking itself will also be altered; the next image seen here “shows how meat has been precisely cut into cubes without leaving any cut marks on the chopping board. The board itself has notches to facilitate robot interaction. In the background the meat package can be seen; it too has been labelled to suggest that the robots operate beyond a single house.”

[Image: From With Robots by Diego Trujillo-Pisanty].

[Image: From With Robots by Diego Trujillo-Pisanty].

In a recent, highly recommended TED Talk, games designer Kevin Slavin discusses how the design of the physical world is being increasingly optimized for algorithms—and one of his central examples is the Roomba self-guided home vacuum cleaner.

[Image: A Roomba reveals its algorithms in this photo by Signal Theorist, via IEEE Spectrum].

[Image: A Roomba reveals its algorithms in this photo by Signal Theorist, via IEEE Spectrum].

The Roomba, in this context, becomes emblematic of the rise of a new kind of device, one with direct spatial and optical effects on the architecture inside of which it functions.

In fact, it is not difficult to imagine, as both Diego Trujillo-Pisanty’s and Kevin Slavin‘s work suggest, a world in which everyday furniture has been subtly redesigned in order to fit the Roomba’s spiraling subroutines—and not the other way around—or even whole rooms peppered with strange, ankle-high optical tags on certain walls, doors, or objects, used to steer the Roomba this way or that at specific points in its room-cleaning operations.

Like a tomb from Egypt’s Valley of the Kings, our houses will be covered in hieroglyphs—machine-hieroglyphs, not legible as much as they are optically recognizable.

Now scale this up to the size of, say, Wall-E, and you get With Robots: a spatial environment slightly, almost invisibly, somehow off, idealized not for human beings at all, but for the spatial needs of intelligent objects.

Subterranean Machine Resurrections

[Image: Photo by Brian Harkin for The New York Times].

[Image: Photo by Brian Harkin for The New York Times].

There is clearly a machines-and-robots theme on the blog this morning. I was fascinated last week to read that New York will soon have “its own subterranean wonder: a 200-ton mechanical serpent’s head” buried “14 stories beneath the well-tended sidewalks of Park Avenue.” In other words, a “gargantuan drill that has been hollowing out tunnels for a train station under Grand Central Terminal” will soon become a permanent part of the city, locked forever in the region’s bedrock. It will be left underground—”entombed” in the words of Michael Grynbaum, writing for the New York Times— lying “dormant and decayed, within the rocky depths of Midtown Manhattan.”

The machine’s actual burial is like a Rachel Whiteread installation gone wrong: “In an official ceremony this week, the cutter will be sealed off by a concrete wall; the chamber will then be filled with concrete, encasing the cutter in a solid cast, Han Solo-style, so that it can serve as a support structure for the tunnel. A plaque will commemorate the site.”

“It’s like a Jules Verne story,” the head of construction for NY’s Metropolitan Transportation Authority endearingly remarked. And the machine itself is an alien wonder:

A recent visit to the cutter’s future crypt revealed a machine that evokes an alien life form that crashed to earth a millennia ago. Its steel gears, bolts and pistons, already oxidizing, appeared lifeless and fatigued. A wormlike fan, its exhaust pipe disappearing into the cutter’s maw, was still spinning, its drone not unlike a slumbering creature’s breath.

I’m tempted to write a short story about a cult of Aleister Crowley-obsessed tower dwellers on the Lower East Side, in the year 2025 A.D., intent on resurrecting this mechanical worm, like something out of Dune, goading it to re-arise, pharaonic and possessed, into the polluted summer air of the city. Grinding and belching its way to dark triumph amidst the buildings, now shattered, that once weighed it down, it is Gotham’s Conqueror Worm.

[Image: Promotional poster for the otherwise unrelated film Conqueror Worm, aka Witchfinder General].

[Image: Promotional poster for the otherwise unrelated film Conqueror Worm, aka Witchfinder General].

But that would be to rewrite something that, to some extent, already exists. In Jonathan Lethem’s recent novel Chronic City, a tunneling machine goes “a little out of control” beneath the surface of New York, resurfacing at night to wreak havoc amongst the boroughs. From the book:

“I guess the thing got lonely—”

“That’s why it destroys bodegas?” asked Perkus.

“At night sometimes it comes up from underneath and sort of, you know, ravages around.”

“You can’t stop it?” I asked.

“Sure, we could stop it, Chase, it we wanted to. But this city’s been waiting for a Second Avenue subway line for a long time, I’m sure you know. The thing’s mostly doing a good job with the tunnel, so they’ve been stalling, and I guess trying to negotiate to keep it underground. The degree of damage is really exaggerated.”

And soon the machine—known as the “tiger”—is spotted rooting around the city, sliding out of the subterranean topologies it helps create, weaving above and below, an autonomous underground object on the loose.

In any case, the entombed drill will presumably outlast the city it sleeps beneath; indeed, if it is ever seen again, it will be a much more geological resurrection. As Alex Trevi of Pruned suggested over email, the machine will be “left there, perhaps forever, and will only surface when NYC rises up in a new mountain range and starts eroding.”

(Thanks to Jessica Young for the reminder about Lethem’s tiger).

Nazca City

[Images: From Ciudad Nasca/Nazca City by Rodrigo Derteano].

[Images: From Ciudad Nasca/Nazca City by Rodrigo Derteano].

we make money not art has posted a short interview with artist Rodrigo Derteano, creator of a project called Ciudad Nasca/Nazca City—a reference to the famed Nazca Lines—in which a semi-autonomous robot tractor has carved a full-scale map of an imaginary city into the Peruvian desert. Watch the video:

The artist remarks that, while sometimes it can be quite melancholy watching the ephemeral geoglyphs of this make-believe robot city disappear a bit each day due to erosion, “most of the time,” he says, “I think it is OK for it to be slowly erased by the wind.”

Perhaps Derteano’s machine secretly built California City.

See more at the artist’s Nazca City blog.

Instruments, Devices and Architectural Inventions

[Image: From The Gray Rush, a new work by The Living, commissioned by the Nevada Museum of Art].

[Image: From The Gray Rush, a new work by The Living, commissioned by the Nevada Museum of Art].

I’m heading up to Reno for the next eight days to install Landscape Futures: Instruments, Devices and Architectural Inventions, an exhibition I’ve guest-curated for the Nevada Museum of Art. I hope to have installation process photos and other glimpses behind the scenes to post later this week.

The exhibition opens to the public on August 13, 2011—although, if you’d like to see the show with participating architects Mark Smout, Liam Young, and David Benjamin, among many others, including myself, consider attending the forthcoming Art + Environment Conference at the Museum, from September 29 to October 1.

Landscape Futures will be on view through February 12, 2012, and was made possible through generous support from the Graham Foundation, the Warhol Foundation, the National Endowment for the Arts, and, of course, through the heroic efforts of the Nevada Museum of Art staff.

Rebooting Massachusetts

[Image: From Redraw, Reboot by Ryan Sullivan].

[Image: From Redraw, Reboot by Ryan Sullivan].

Designer Ryan Sullivan recently got in touch with Redraw, Reboot, a series of new maps for the U.S. state of Massachusetts.

[Image: From Redraw, Reboot by Ryan Sullivan].

[Image: From Redraw, Reboot by Ryan Sullivan].

Sullivan’s maps “explore new boundaries for municipalities in the Commonwealth of Massachusetts,” he explained. “They range from a John Wesley Powell-inspired watershed map to a Voronoi-driven Dunkin’ Donuts township map.”

[Images: From Redraw, Reboot by Ryan Sullivan].

[Images: From Redraw, Reboot by Ryan Sullivan].

The project began with a series of questions: What if the official internal boundaries of Massachusetts were entirely erased? “How would we redraw them? And how could new municipal boundaries better align government with our needs today?”

Many of Massachusetts’ town lines were based on geographic features; forgotten disputes among parishes; long-dead landowners’ property lines; and, yes, craven political gamesmanship—this is, after all, the state that invented the gerrymander. Now, as the Commonwealth contends with the politics of congressional redistricting, we realize how arbitrary many of these designations are.

Of course, Sullivan’s suggested replacements are less serious political proposals than whimsical parameters for a surreal new state to come—its jurisdictions defined, for instance, by doughnut consumption—but if we are to redesign the political units through which contemporary governance functions, I suppose you have to start somewhere.

In any case, the images seen here are just a glimpse; they were all originally published in and commissioned by ArchitectureBoston.

Twisty little passages

Churchyards and private farmlands throughout the German state of Bavaria are perforated from below by “more than 700 curious tunnel networks” whose “purpose remains a mystery.”

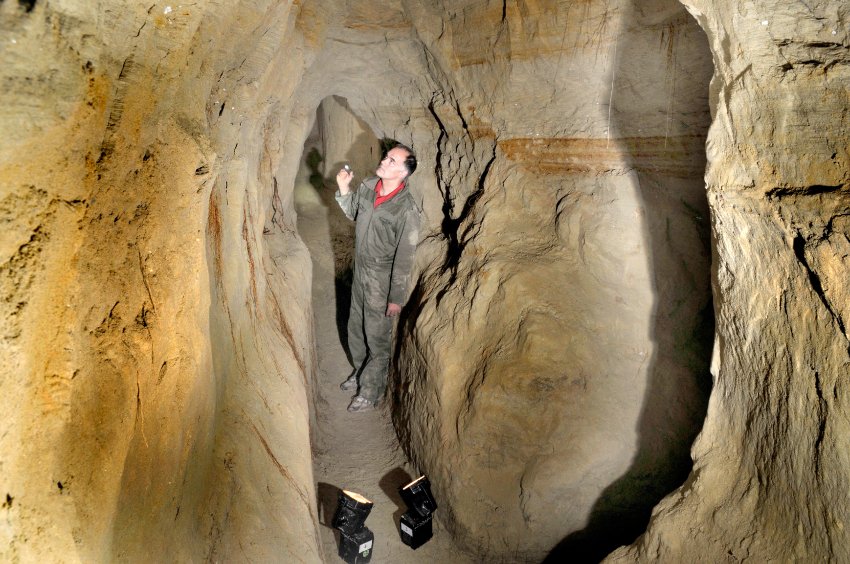

[Image: Photograph by Ben Behnke courtesy of Der Spiegel].

[Image: Photograph by Ben Behnke courtesy of Der Spiegel].

As Der Spiegel reports, “The tunnel entrances are sometimes located in the kitchens of old farmhouses, near churches and cemeteries or in the middle of a forest. The atmosphere inside is dark and oppressive, much as it would be inside an animal den.”

Although the subterranean networks are considered an “extremely unusual ancient phenomenon,” other “small underground labyrinths have been found across Europe, from Hungary to Spain, but no one knows why they were built.”

[Image: Diagram courtesy of Der Spiegel].

[Image: Diagram courtesy of Der Spiegel].

Small might actually understate the case: indeed, “the tunnels are often only 20 to 50 meters long. The larger passageways are big enough so that people can walk through them in a hunched position, but some tunnels are so small that explorers have to get down on all fours. The tiniest passageways, known as “Schlupfe” (“slips”), are barely 40 centimeters (16 inches) in diameter.”

[Image: Photographs by Ben Behnke courtesy of Der Spiegel].

[Image: Photographs by Ben Behnke courtesy of Der Spiegel].

I’m particularly fascinated by examples of these tunnels being found on what is now private property. For instance, a family named the Greithanners, “from the town of Glonn near Munich, are the owners of a strange subterranean landmark. A labyrinth of vaults known as an Erdstall runs underneath their property. It is at least 25 meters (82 feet) long and likely stems from the Middle Ages.” I’m genuinely curious what the legal status of such discoveries might be. If, for instance, you discover someday that your house sits atop hundreds of feet of artificially excavated underground space from the Middle Ages, do your property taxes go up—or down, due to the structural inconvenience of owning land hollowed out from below?

[Image: Reasons to be cheerful; photo by Ben Behnke, courtesy of Der Spiegel].

[Image: Reasons to be cheerful; photo by Ben Behnke, courtesy of Der Spiegel].

In any case, Der Spiegel goes on to explain how local archaeologists (who, in order to avoid underground suffocation, once “blew air into a tunnel with a ‘reversible vacuum cleaner'”) have teamed up with engineers to explore these spaces—including a man named Nikolaus Arndt, who earlier in his career helped to build the Great Man-Made River of Libya. For now, the tunnels’ original purpose still remains unclear:

The vaults could not have served a practical purpose, as dwellings or to store food, for example, if only because the tunnels are so inconveniently narrow in places. Besides, some fill up with water in the winter. Also, the lack of evidence of feces indicates that they were not used to house livestock.

There is not a single written record of the construction of an Erdstall dating from the medieval period. “The tunnels were completely hushed up,” says [Dieter Ahlborn, leader of the Working Group for Erdstall Research].

Archeologists have also been surprised to find that the tunnels are almost completely empty and appear to be swept clean, as if they were abodes for the spirits. One gallery contained an iron plowshare, while heavy millstones were found in three others. Virtually nothing else has turned up in the vaults.

The rest of the occasionally bizarre article—one of the locals, for instance, says that sitting alone inside an Erdstall makes him “feel like a Hopi Indian”—is worth reading, though any hope that these tunnels might someday be found to rival the discovery of Derinkuyu should, alas, be put aside. Read more at Der Spiegel.

(Thanks to Derek Upham for the tip!)