Building booms are a dime a dozen lately. The earth’s surface is being processed, ordered, stacked, shipped, registered and reconfigured into “architecture” elsewhere. Materials, mineral wealth, reserves.

Even in unexpected places and global blindspots, as Ürümqi now testifies. Ürümqi? It’s the capital of Xinjiang, China’s northwesternmost desert province. Recently, William Beeman wrote that Ürümqi “looks like lower Manhattan, with skyscrapers rising almost in front of one’s eyes.”

“The city, a century ago [sic: only a century?] a major stop on the Silk Road, is flourishing again with economic activity doubling every year. The city is becoming the mercantile trade capital of all Central Asia, and there is not an American in sight. In fact, aside from a few intrepid German tourists, there are no westerners to be seen anywhere.”

Ürümqi, Beeman writes, “is clean and bustling 24 hours a day. It is clearly a shopper’s paradise with huge bazaars everywhere. One ‘bazaar’ is nothing but a four-storey building full of small offices representing every possible Chinese manufacturer or distributor of consumer goods – from cashmere shawls to computer chips. Of U.S. companies, only Nike is present. All the signs in the complex are in Chinese, Russian and Uighur, a member of the Turkic family and the official language of Xinjiang.”

A brief biographical note here: I spent four months in Beijing in the summer of 1997, living with a Chinese student called Abraham. We watched fireworks explode over Tiananmen Square the night Hong Kong turned its back on Cornish pasties, the Spice Girls and Pret-a-Manger to become geographically Chinese once again. Our shared little breeze-block dorm room was only steps away, through the narrow between-space of an alley that twisted away from the high street, from what we called Uighurville. I’d buy large loaves of flatbread there and realized that, even in the middle of the capital of China, there were other people as foreign as I was, and it wasn’t because they were “foreigners” as such; it was their desert religion, and their social movements, and their noodle bowls, all, in effect, internally colonized. To live in a country does not mean that you are of that country.

In any case, Tajik entrepreneurs, Chinese tourists, Uighur college students, Russian dumplings – Ürümqi is “a booming economy operating outside of Western influence, combined with ethnic tensions that are already proving explosive”.

So while Ürümqi booms – and Shanghai, and Beijing itself, and the whole of Guangdong – what do you know but Moscow is also in on this, too: in the August 2005 Architectural Record, Paul Abelsky writes: “While the world focuses on Beijing and Shanghai as the new centers of building construction, Russia’s capital, Moscow, is undergoing a transformation unmatched since the massive overhaul of the Stalin era. The building boom has overtaken huge swathes of the city (…) [and] about 50 million square feet of housing were added. Public officials have spoken of building 38 high-rises of up to 45 stories in the next several years, with 22 more expected by 2015 as part of a program known as the New Ring of Moscow.”

“The planned series of towers and modern infrastructure promise an infusion of high-tech energy whose vertical extension will resemble Kuala Lumpur and Shanghai more than a European metropolis.”

Norman Foster, Zaha Hadid, Rem Koolhaas.

Then there’s the “Moscow-City” district (surely there’s a novel in that name! a whole series of something-or-other mystery/horror/spy thriller novels?), “a sector northwest of the city center that has been designated as the future administrative and financial nucleus.”

Recall Berlin in the 1990s. Of course, the new Economist City Guide newsletter about Berlin informs us that, today, “[t]he number of flats in Berlin has risen by 6% to an astonishing 1.88m over the past six years. That’s one flat for every 1.8 Berliners,” or “what gives Berlin its youthful buzz: 920,000 (or 27.6%) of the city’s residents are under the age of 27. They are growing used to having plenty of personal space, since the average flat in Berlin measures 70 square metres.” Another way of saying that, however, is that they built too much.

Bahrain, meanwhile, in forecasting the end of the oil economy, is setting itself up, through yet another building boom, to become a tourist attraction and offshore financial services hub. To do so, Bahrain has turned to “innovative offshore developments and land reclamation projects.”

Then there’s Baghdad, and “Bremer walls” (huge, ubiquitous, monolithic concrete blast shields –

– somewhere between Stonehenge and fortress urbanism, and named after the well-groomed Mr. Paul Bremer himself [a former reinsurance executive: this PDF is amazingly informative in that regard]), and this article about Lieutenant James Vandenberg’s tour of duty as a “combat architect” in that fabled city.

Finally, because I’m running out of steam: London. LNDN.bldg.

London now looks forward to “31 major new developments… all £100bn worth of them, including the 2012 Lea Valley Olympic Park.” That equates to “400,000 new homes, around 8m square feet of new offices (four Empire State Buildings’ worth),” as well as “so many secret, or simply obscure, developments” that the New London Architecture centre (aka NLA) was created at least partially to help make sense of it all.

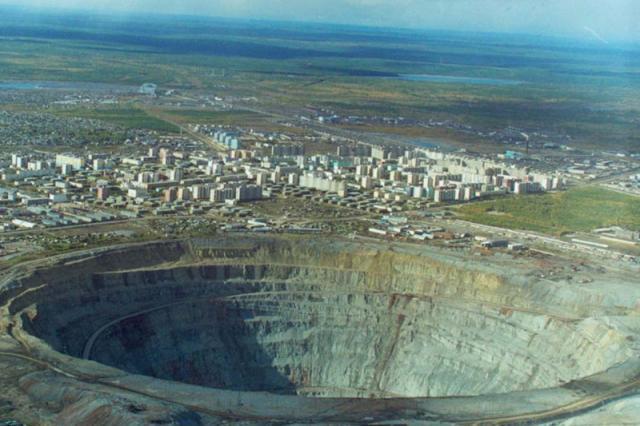

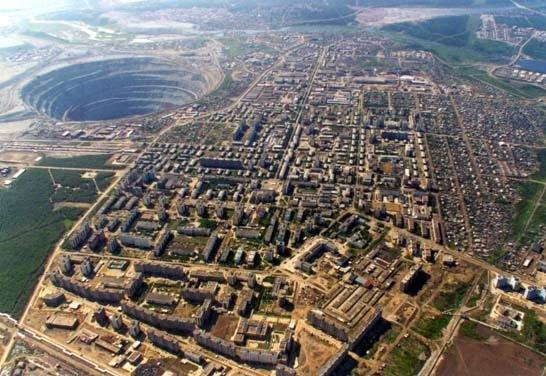

Brief questions: where is all this material coming from? I know new earth’s crust is continually being formed near the core/mantle boundary, for instance, and that superplumes of volcanic matter form massive geological features such as the Ontong-Java undersea Plateau, but you can only build so much architecture before you start to carve quite deeply into the planet. So: where are the negative spaces of these building booms? For every skyscraper in Ürümqi, is there a corresponding hole, quarry, or mine being dug or deepened somewhere in Kazakhstan? Or Montana? The Canadian arctic?

Like the urban geology walks mentioned in a recent BLDGBLOG post, could you do a geophysical tour of the earth’s voids, where huge quantities of mineral reserves and raw metals have been excavated, to say: this was Shanghai? Here is the hole that was transformed into Beijing?

The empty flats of Berlin, the New Ring of Moscow, New London Architecture – all rearrangements, transformations of the void, ever-deepening holes as we strip-mine the face of the planet.

[Image: The Mirny diamond mine; photographer unknown].

[Image: The Mirny diamond mine; photographer unknown].

[Images: Mirny diamond mine; photographers unknown].

[Images: Mirny diamond mine; photographers unknown]. [Image: The Mirny diamond mine; photographer unknown].

[Image: The Mirny diamond mine; photographer unknown].