[Image: “Glowing, silvery blue clouds that have been spreading around the world and brightening mysteriously in recent years will soon be studied in unprecedented detail by a NASA spacecraft.” New Scientist].

Some unrelated items of atmospheric news…

First, the phenomenon of “noctilucent clouds” is under investigation. These are clouds “which glow at night, form in the upper atmosphere, at an altitude of about 80 kilometres, and their glow can be seen just after sunset or just before sunrise. ‘Even though the Sun’s gone down and you’re in darkness, the clouds are so high up, the Sun is still illuminating them.'”

However, could a city deliberately build upward curving traps of air, thermally concentrating moisture in huge, rising chimneys, giving its citizens a kind of Air TV – abstract films of silvery blue clouds coiling across the sky, mercurial and noctilucent? Gone would be Seasonal Affective Disorder; in its place you’d have this fairy tale gossamer light, glowing metallic on the edges of all things. Add to that the microscopic sounds of water crystallizing inside distant clouds – amplified throughout the canyons of the city – and you’d have a kind of climatopia.

Meanwhile, “many of the skyscrapers in Shanghai could become quite dangerous” due to the high winds they’re now producing. This effect is seemingly parodied in Mission Impossible III when Tom Cruise parachutes out of a Shanghai skyscraper – only to find that his chute fails to open due to the torque of neon whirlwinds lashing him about between corporate bank towers. (Yes, I’ve seen Mission Impossible III).

In an inadvertant moment of architectural criticism, “the Shanghai municipal government identified skyscrapers as one of the biggest potential threats to the city.”

Ages ago, in a no doubt now embarrassing BLDGBLOG post, the idea of urban wind-guns was explored, wondering, simultaneously, what impact surburban tract housing might have on the storms that eventually blow through a city. Fences, back porches, forests cut down or left to grow: how do these affect the speed of regional wind systems?

[Image: By krisstr, from the Shanghai Flickr group].

Shanghai city authorities have more or less answered that question, suggesting that “more trees can be planted to block part of the winds,” and that “the walls of the buildings should be fortified while notice signs are put up to signal potentially dangerous areas.” Pockets of atmospheric turbulence within the city. (How do skyscrapers affect the flight-paths of airplanes?)

Finally, air wells, tropospheric rivers, and electromagnetic weather control all meet in this surprisingly long but very interesting article.

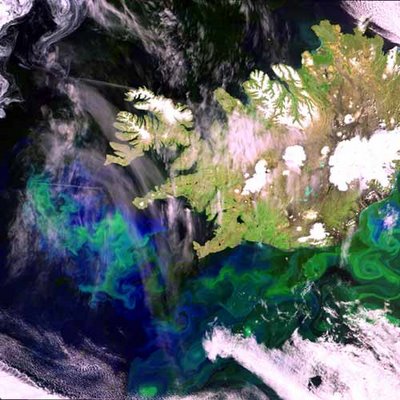

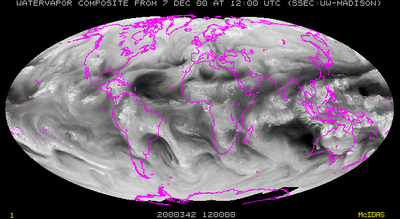

There, we discover that “huge filamentary structures” in the sky act as “preferable pathways of water vapor movement in the troposphere (the lower 10-20 km of the atmosphere) with flow rates of about 165 million kilograms of water per second. These ‘atmospheric rivers’ are bands from 200 to 480 miles wide and up to 4,800 miles long, between 1-2 kilometers above the earth. They transport about 70% of the fresh water from the equator to the midlatitudes, are of great importance in determining the location and amount of winter rainfall on coastlines.”

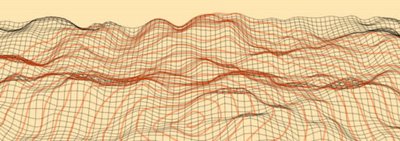

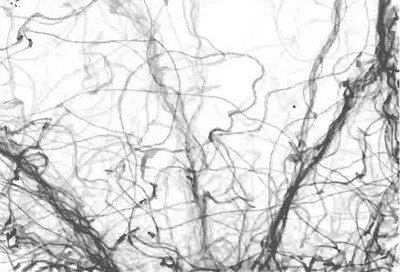

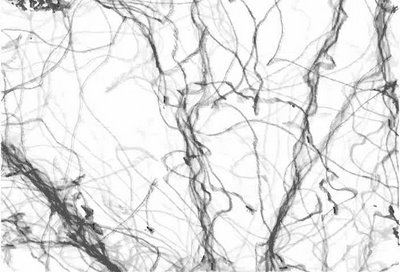

[Image: The aforementioned tropospheric rivers, a kind of fluted cobwebbing of intercontinental air pressure].

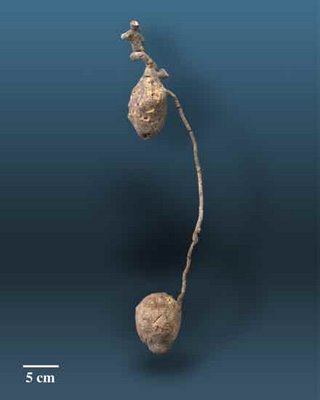

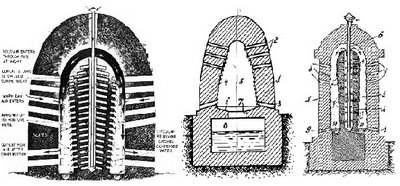

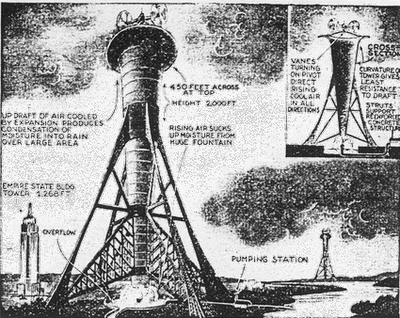

The following devices – towers, air wells, etc. – were all designed to help tap into these rivers, turning the sky itself into an aquatic reservoir.

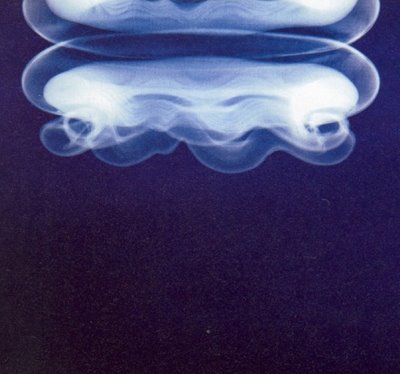

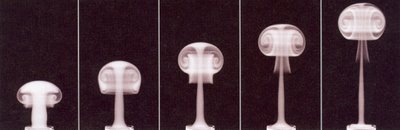

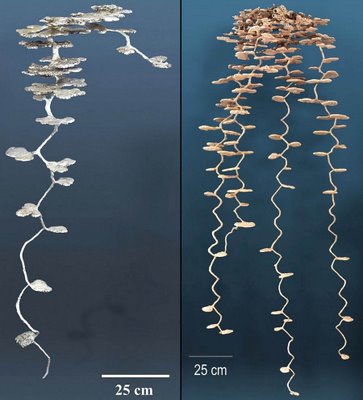

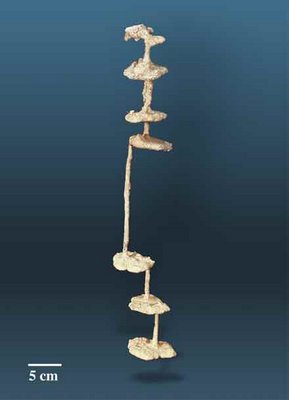

You basically build one of those things at a geo-atmospherically strategic location; you make youself a cup of tea; their height and geometry trigger downdrafts; then the internal chambers cause condensation of vapor from air. Thus, an air well. The end of drought through tropospheric riverways.

Here’s a diagram of one of the machines working:

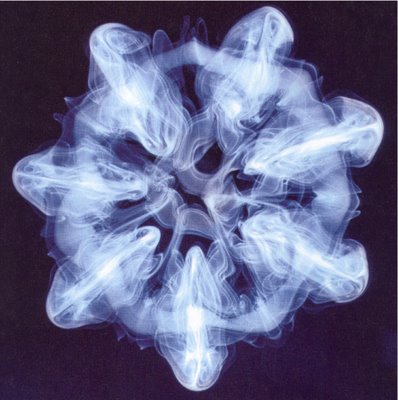

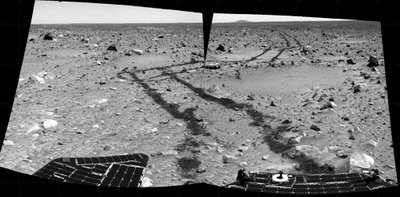

The article, of course, also discusses electromagnetic weather control, such as the notorius HAARP Project, pictured here –

– but there’s a (very little) bit more on that in an earlier post.

(Thanks to Scott Webel for the air wells article; and to the incomparable things magazine for the link about Shanghai).