[Image: Castle Rushen, Castletown, Isle of Man, via Old UK Photos].

[Image: Castle Rushen, Castletown, Isle of Man, via Old UK Photos].

I was poking around for images this morning and I somehow ended up at a site called Old UK Photos. They collect old, public domain photographs of the UK (rather cheekily including Ireland) – but some of the photos are so extraordinarily beautiful, and so hard to believe that they really are photographs, that I felt like re-posting a few here.

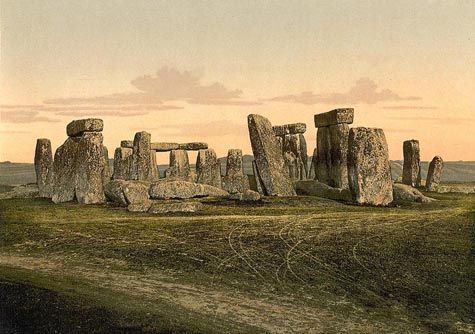

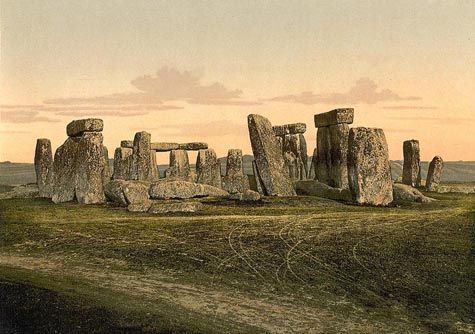

[Image: Wiltshire, Salisbury Plain, Stonehenge, via Old UK Photos].

[Image: Wiltshire, Salisbury Plain, Stonehenge, via Old UK Photos].

The fact that I’ve also been to many of these places adds a weird layer of delayed misrecognition to many of the scenes, as if stumbling upon landscapes from trips I forgot I’d taken (which is almost accurate).

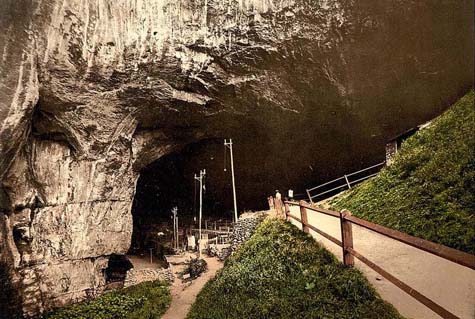

The old pier in Bangor. One of the Peak District caves. Edinburgh castle.

And, of course, Stonehenge, pictured above from those years in which it hadn’t yet been fenced off.

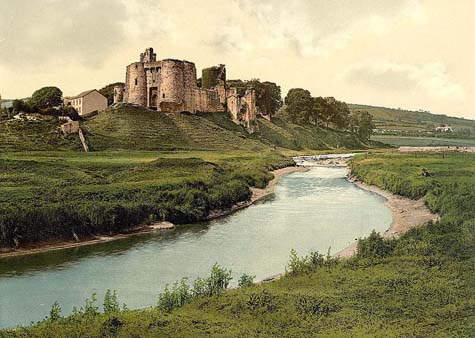

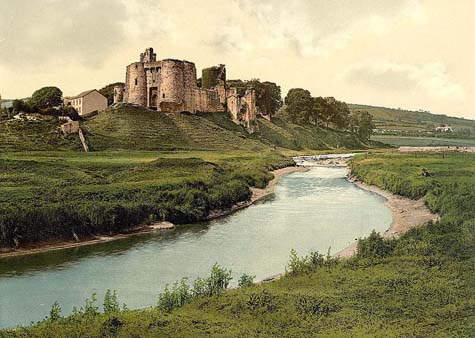

[Image: Caerlaverock Castle, Dumfriesshire; Peel Cathedral, Isle of Man; castle in Aberystwyth, Cardiganshire; castle in Kidwelly, Carmarthenshire; Peel Castle, Isle of Man; and Ballower Mount, Ramsey, Isle of Man; all via Old UK Photos].

[Image: Caerlaverock Castle, Dumfriesshire; Peel Cathedral, Isle of Man; castle in Aberystwyth, Cardiganshire; castle in Kidwelly, Carmarthenshire; Peel Castle, Isle of Man; and Ballower Mount, Ramsey, Isle of Man; all via Old UK Photos].

I don’t have all that much to say about these, in fact, other than to point out that they seem to instill something between nostalgia (for myself, an Anglo-American) and a wistful need to travel through non-automobile-based landscapes – and perhaps even a somewhat Gothicized sense of fictive possibilities, like something out of BLDGBLOG’s recent interview with novelist Patrick McGrath.

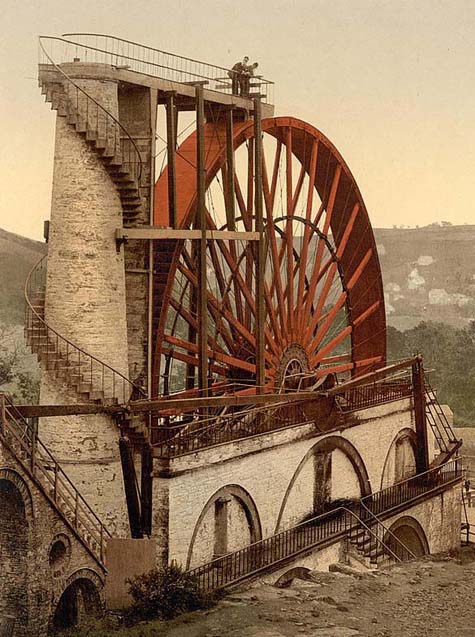

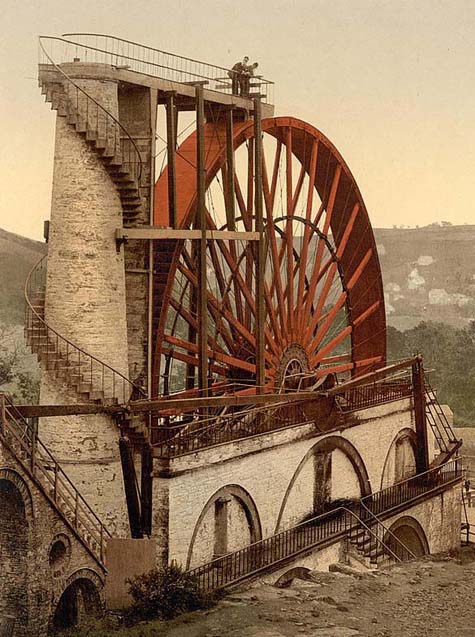

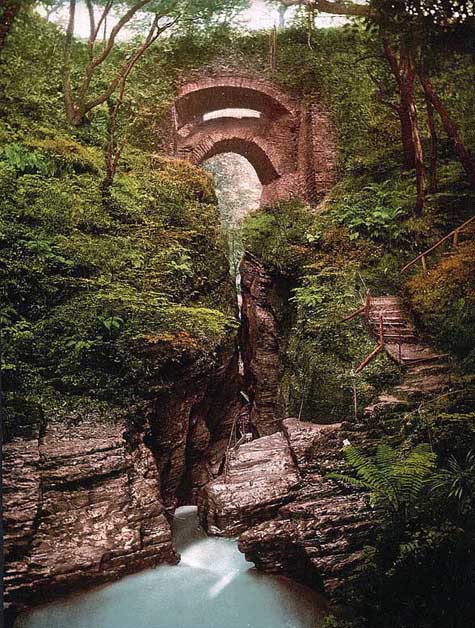

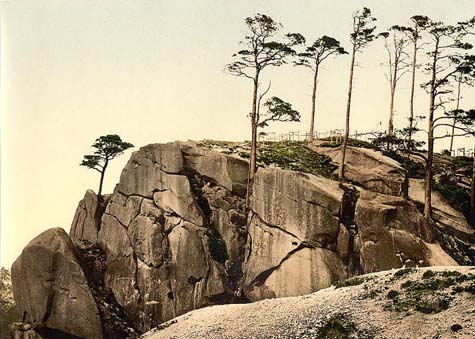

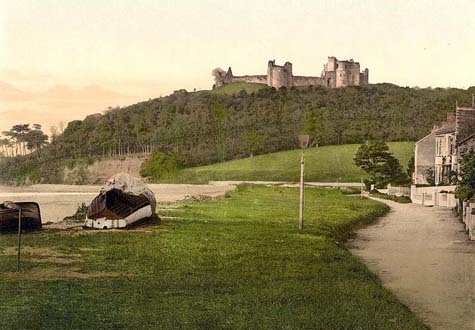

That said, then, here are some photos, with crumbling castles on distant hills and even mysterious pieces of old machinery.

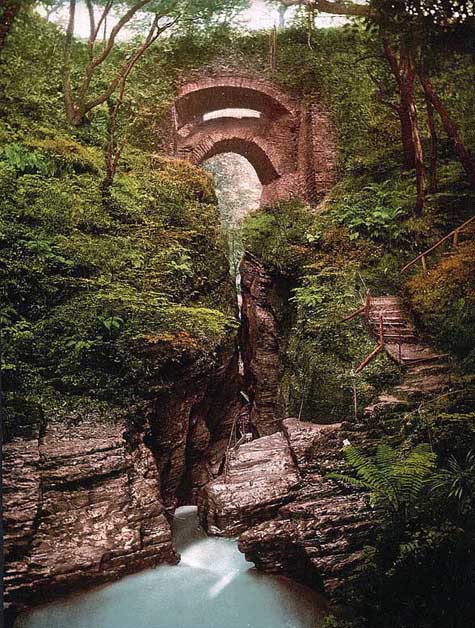

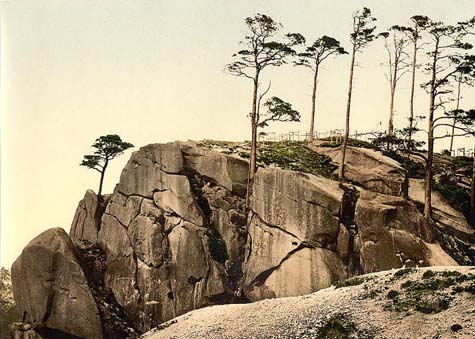

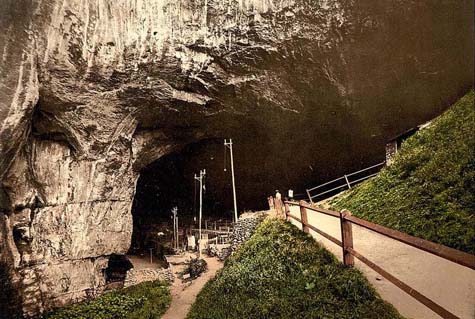

[Images: Castle at Bolsover, Derbyshire; castle in Kidwelly, Carmarthenshire; bridge in Carmarthen, Carmarthenshire; the Wheel at Laxey, Isle of Man; Devil’s Bridge, Aberystwyth; Templand Bridge, Cumnock, Ayrshire; The Blackrock in Cromford, Derbyshire; entrance to a cave outside Castleton, Derbyshire; all via Old UK Photos].

[Images: Castle at Bolsover, Derbyshire; castle in Kidwelly, Carmarthenshire; bridge in Carmarthen, Carmarthenshire; the Wheel at Laxey, Isle of Man; Devil’s Bridge, Aberystwyth; Templand Bridge, Cumnock, Ayrshire; The Blackrock in Cromford, Derbyshire; entrance to a cave outside Castleton, Derbyshire; all via Old UK Photos].

Some of the coastal photographs – of bays, inlets, coves, rock arches, and cliffs – seem to imply a labyrinthine island geography so complicated and ornate in its expanse, and so remote, that people still must be discovering new places there today… But then, of course, that describes the British Isles. Unless you spend all your time in Leicester Square.

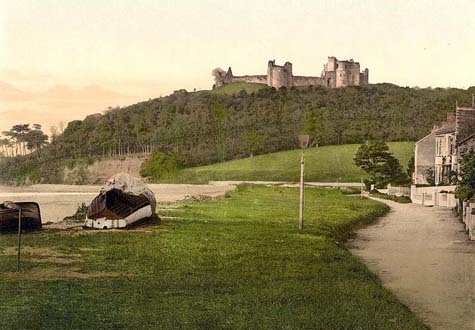

[Images: Castle in Llanstephan, Carmarthenshire; Petite Bot, Guernsey, Channel Islands; La Coupee, Sark, Channel Islands; Dixcart Bay, Sark; Sugarloaf Rock at Port St. Mary, Isle of Man; the coast at the Gouffre, Petite Bot, and the harbor at La Moye Point (3 images), Guernsey; via Old UK Photos].

[Images: Castle in Llanstephan, Carmarthenshire; Petite Bot, Guernsey, Channel Islands; La Coupee, Sark, Channel Islands; Dixcart Bay, Sark; Sugarloaf Rock at Port St. Mary, Isle of Man; the coast at the Gouffre, Petite Bot, and the harbor at La Moye Point (3 images), Guernsey; via Old UK Photos].

Actually, I’m reminded of something I read a few years ago in a book called The Dragon Seekers: How an Extraordinary Circle of Fossilists Discovered the Dinosaurs and Paved the Way for Darwin – which is that a particular stretch of British coastline, near Lyme Regis, is full of fossils.

The book opens with the story of Mary Anning, an amateur “fossilist” – she made an income selling bits of backbones and fragments of mastodons, jigsaw puzzle-like pieces of species that no longer exist – who stumbled upon, if I remember correctly, the body of an ichthyosaur – but only because there had been a landslide. Without that tidally inspired collapse of a nearby cliff, Anning perhaps would never have found her fossil; it would have remained buried in the cliffside for years – decades, centuries – to come.

Although she had an eye for fossils, she could not find them until they had been exposed by weathering – an achingly slow process. But when wind and rain and frost and sun had done their work, she would find them, peeking through the surface. Others were buried so deeply in the cliffs that it would be aeons before they were ever discovered.

The idea that the fossils of as yet undiscovered creatures still lie buried somewhere in the cliffs of Dorset is almost overwhelmingly interesting.

In any case, the bottom two images are from Bangor, Wales, where my brother and I once stayed in a youth hostel and ate soup. We hiked outside of town one afternoon and we looked up at a tree covered in drooping sleeves of loose vegetation, then we fell asleep on a hillside in some farmyard nearby, jumping over a fence and lying down amidst lichen-covered rocks and small bushes.

In fact, I’m a little embarrassed to admit this, but I was reading The Lord of the Rings and so the whole experience was tinged with an air of the mythic.

[Images: Garth’s Pier in Bangor, Caernarfonshire, and a view of Bangor from Anglesey, via Old UK Photos].

[Images: Garth’s Pier in Bangor, Caernarfonshire, and a view of Bangor from Anglesey, via Old UK Photos].

Anywho, the old lighthouse at Corbiere, on the Channel Island of Jersey, makes a nice painterly silhouette in this next photo.

[Image: The lighthouse at Corbiere, Jersey, Channel Islands, via Old UK Photos].

[Image: The lighthouse at Corbiere, Jersey, Channel Islands, via Old UK Photos].

And the old paths still whirl and turn through hills, leading somewhere, going everywhere.

[Image: Moulin Huet, Guernsey, Channel Islands, via Old UK Photos].

[Image: Moulin Huet, Guernsey, Channel Islands, via Old UK Photos].

All of these images, plus a few more, are also saved in a Flickr set I put together this afternoon.

(The title of this post paraphrases a line from William Blake’s poem Milton. Meanwhile, it may not be entirely related to the images in this post, but I do recommend giving at least a quick read to BLDGBLOG’s interview with Patrick McGrath for some thoughts on the literary impact of these – or similar – landscapes).

[Image: A suburban house that is otherwise unconnected to this post].

[Image: A suburban house that is otherwise unconnected to this post]. [Image: Toxic black mold].

[Image: Toxic black mold].

[Image: Surveillance cameras for sale in China; photo by Timothy O’Rourke for

[Image: Surveillance cameras for sale in China; photo by Timothy O’Rourke for  [Image: Surveillance in China; photographer temporarily unknown, though this appeared in

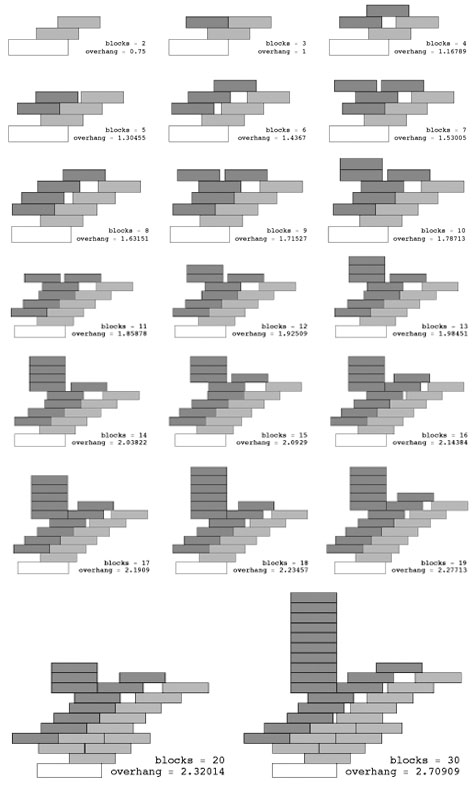

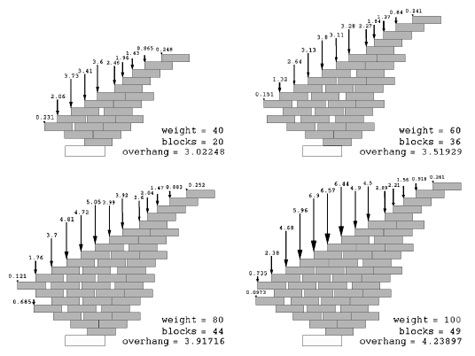

[Image: Surveillance in China; photographer temporarily unknown, though this appeared in  [Image: The diagrammatic mathematics of a structural experiment by

[Image: The diagrammatic mathematics of a structural experiment by  [Image: Two abstract stacks by

[Image: Two abstract stacks by  [Image: May the force stack with you; diagram by

[Image: May the force stack with you; diagram by  [Image: More stack madness by

[Image: More stack madness by  [Image: London’s P&O Building gets demolished in reverse; via the

[Image: London’s P&O Building gets demolished in reverse; via the  [Image: View

[Image: View  It’s not a planet at all, then, but a bio-electrical deposit rotating in space. A living battery.

It’s not a planet at all, then, but a bio-electrical deposit rotating in space. A living battery. [Image: Castle Rushen, Castletown, Isle of Man, via

[Image: Castle Rushen, Castletown, Isle of Man, via  [Image: Wiltshire, Salisbury Plain, Stonehenge, via

[Image: Wiltshire, Salisbury Plain, Stonehenge, via

[Image: Caerlaverock Castle, Dumfriesshire; Peel Cathedral, Isle of Man; castle in Aberystwyth, Cardiganshire; castle in Kidwelly, Carmarthenshire; Peel Castle, Isle of Man; and Ballower Mount, Ramsey, Isle of Man; all via

[Image: Caerlaverock Castle, Dumfriesshire; Peel Cathedral, Isle of Man; castle in Aberystwyth, Cardiganshire; castle in Kidwelly, Carmarthenshire; Peel Castle, Isle of Man; and Ballower Mount, Ramsey, Isle of Man; all via

[Images: Castle at Bolsover, Derbyshire; castle in Kidwelly, Carmarthenshire; bridge in Carmarthen, Carmarthenshire; the Wheel at Laxey, Isle of Man; Devil’s Bridge, Aberystwyth; Templand Bridge, Cumnock, Ayrshire; The Blackrock in Cromford, Derbyshire; entrance to a cave outside Castleton, Derbyshire; all via

[Images: Castle at Bolsover, Derbyshire; castle in Kidwelly, Carmarthenshire; bridge in Carmarthen, Carmarthenshire; the Wheel at Laxey, Isle of Man; Devil’s Bridge, Aberystwyth; Templand Bridge, Cumnock, Ayrshire; The Blackrock in Cromford, Derbyshire; entrance to a cave outside Castleton, Derbyshire; all via

[Images: Castle in Llanstephan, Carmarthenshire; Petite Bot, Guernsey, Channel Islands; La Coupee, Sark, Channel Islands; Dixcart Bay, Sark; Sugarloaf Rock at Port St. Mary, Isle of Man; the coast at the Gouffre, Petite Bot, and the harbor at La Moye Point (3 images), Guernsey; via

[Images: Castle in Llanstephan, Carmarthenshire; Petite Bot, Guernsey, Channel Islands; La Coupee, Sark, Channel Islands; Dixcart Bay, Sark; Sugarloaf Rock at Port St. Mary, Isle of Man; the coast at the Gouffre, Petite Bot, and the harbor at La Moye Point (3 images), Guernsey; via

[Images: Garth’s Pier in Bangor, Caernarfonshire, and a view of Bangor from Anglesey, via

[Images: Garth’s Pier in Bangor, Caernarfonshire, and a view of Bangor from Anglesey, via  [Image: The lighthouse at Corbiere, Jersey, Channel Islands, via

[Image: The lighthouse at Corbiere, Jersey, Channel Islands, via  [Image: Moulin Huet, Guernsey, Channel Islands, via

[Image: Moulin Huet, Guernsey, Channel Islands, via  [Image: The Crucifixion as seen via Google Earth; by

[Image: The Crucifixion as seen via Google Earth; by

[Image: Biblical scenes as seen via Google Earth; by

[Image: Biblical scenes as seen via Google Earth; by  [Image: Chartres Cathedral as rendered in

[Image: Chartres Cathedral as rendered in  [Image: The Kaiser Shipyard’s

[Image: The Kaiser Shipyard’s  [Image: The warehouse at night, photographed by

[Image: The warehouse at night, photographed by  [Image: Nested salt shakers spotted on Dezeen… Wait a minute – it’s

[Image: Nested salt shakers spotted on Dezeen… Wait a minute – it’s  [Image: Illustration by Andrew Norfolk for

[Image: Illustration by Andrew Norfolk for