“Who would want to be an architect?” the Times asks. In answering that question, the article focuses more or less entirely on London’s Bartlett School of Architecture—whose students have been producing some amazing work lately, work that I have often posted about here on BLDGBLOG. Here, here, here, and here, for instance.

But, the article claims, “Leave the future to Bartlett students and we’ll all be living in car-crash spaces that occasionally come into focus as giant mechanised spindly crustacea.”

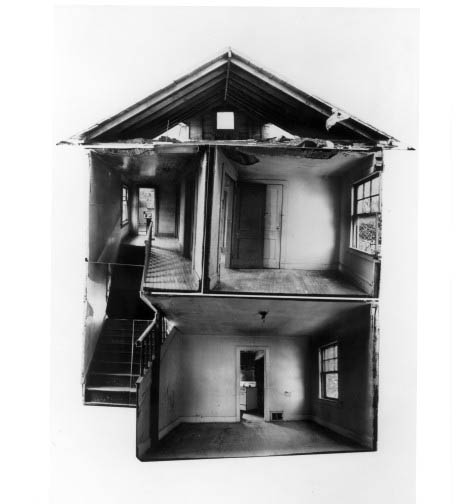

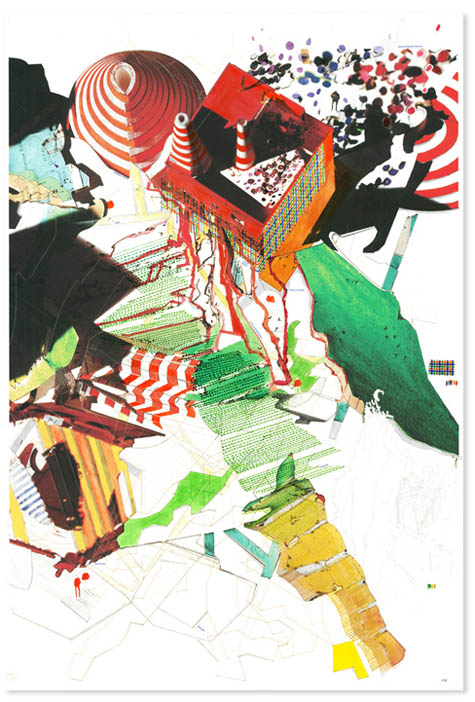

[Image: “Oops” by C. Loopus].

[Image: “Oops” by C. Loopus].

Reading such things easily prompts the familiar zing of schadenfreude—but it also seems totally inaccurate. If only it were as cut-and-dried as mistaking student work for what someone will produce professionally later; if only it were as easy as extrapolating from someone’s earliest university sketchbooks to see how they’ll someday end up.

I’m reminded here of Lebbeus Woods’s recent short essay on the work of Rem Koolhaas: there was “another Rem,” Lebbeus writes. Looking back at one of Rem’s early projects—an unsuccessful bid for the Parc de la Villette in Paris—Lebbeus suggests:

This project reminds us that there was once a Rem Koolhaas quite different from the corporate starchitect we see today. His work in the 70s and early 80s was radical and innovative, but did not get built. Often he didn’t seem to care—it was the ideas that mattered.

Over on his own blog, Quang Truong puts it more simply: “Young Koolhaas was just so punk.”

(Of course, parenthetically, Truong’s formulation opens up a whole series of possible readings through which we could interpret Rem’s ongoing career moves; we could say, for instance, that Rem is still “punk,” to use that term deliberately, but his decisions to work for clients like the Chinese government are just him giving the finger to you. That is, if punk is a universal form of energetic rebellion, then don’t assume that every punk will remain forever on your side).

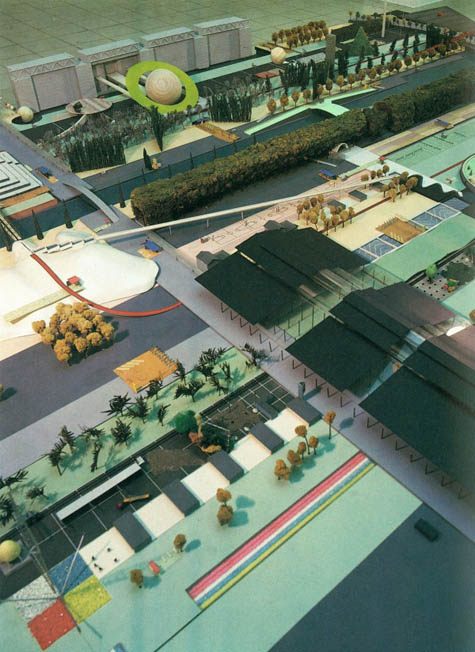

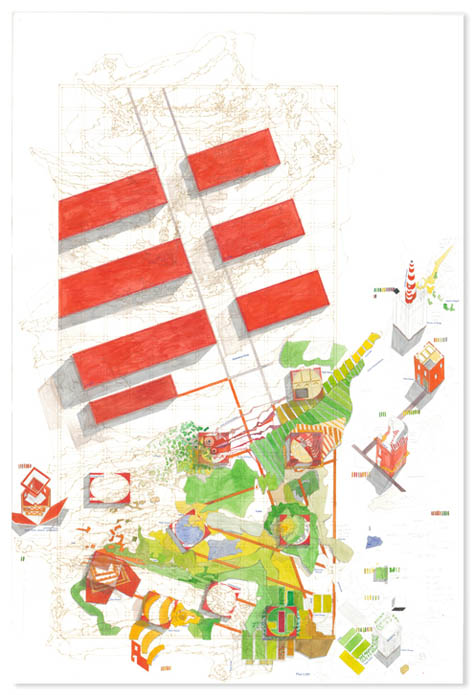

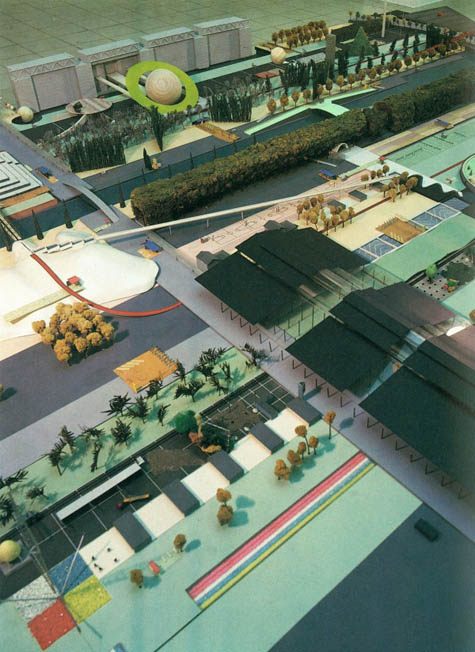

[Image: From Rem Koolhaas’s unbuilt proposal for the Parc de la Villette in Paris, via Lebbeus Woods].

[Image: From Rem Koolhaas’s unbuilt proposal for the Parc de la Villette in Paris, via Lebbeus Woods].

In any case, my point in citing Lebbeus’s essay in this context is to agree with the Times that student work can often stand on the absolute fringes of incomprehensibility, charged with the energy of poetry, myth, or confrontational politics, even verging on functional uselessness—but it’s also an ongoing joke at nearly every architecture crit I’ve been to over the past few years that, upon surviving their final day of project criticism, those students “can now get back to designing minimalist boxes.” In other words, there simply is not the assumption in these studios that now you are prepared only for the construction of rhizomes and biomorphopedic multi-agent typology swarms. There is obviously a problem if that is all you have been taught to do; but it’s not one or the other. Being taught how to make short films about architecture—more on this, below—doesn’t mean you can’t simultaneously be taught how to renovate a kitchen or how to market yourself to new clients.

The fact of the matter, anyway, is that very few clients today will actually pay to construct “car-crash spaces that occasionally come into focus as giant mechanised spindly crustacea.” If architecture school is the only time and place in which you can have the freedom to explore that sort of thing, then I don’t see any reason why you should be told not to do so. Again, if that’s all your architecture school offers you, leaving you alone to sort out the business of client management as you go, then of course your educational track needs reconsidering.

However, much of the Times‘s criticism seems predicated on the assumption that, if architecture is a vocational trade, similar to plumbing, then it cannot simultaneously be an expressive art, akin to film, painting, or literature. But, of course, it is both. In fact, the controversy more or less instantly disappears: architecture is the imaginative production of future worlds even as it is the act of building houses for the urban poor or the obtaining of technical skills necessary for rationally subdividing office floorplates.

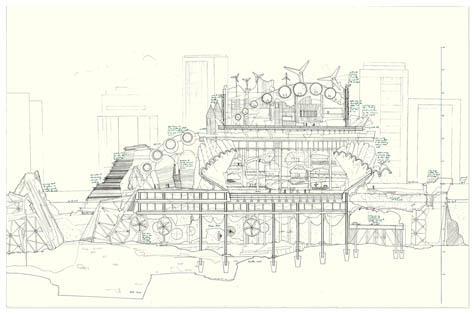

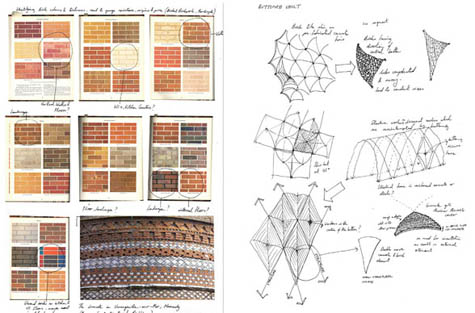

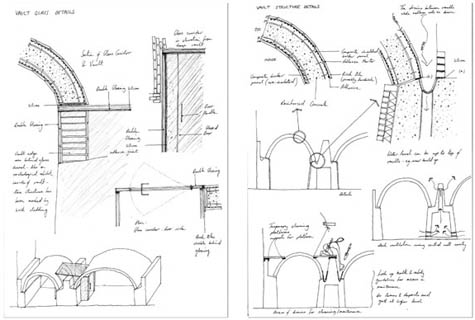

[Image: From a project by Margaret Bursa for the Bartlett’s Unit 11, taught by Smout Allen].

[Image: From a project by Margaret Bursa for the Bartlett’s Unit 11, taught by Smout Allen].

Having said all this, the Times article ends up being a formulaic list of reasons why such-and-such an industry is doomed to fail—too many people want to pursue it, we read, not enough people want to fund it, and hardly anyone understands anymore what made it so popular in the first place. But replace the word “architecture” with “writing,” and “Bartlett School of Architecture” with “Iowa Writers Workshop”—or use “music” and “Mills College”—and you’d get a nearly identical article.

There are some very real questions to ask about the nature of architectural education today—and, when it comes to things like how architects write, I am probably in agreement with the author of the Times article (and with many of the students quoted in the piece)—but holding up the overall profitability of the industry, and the likely financial success of its individual practitioners, as the only criteria by which we should judge an architecture school seems absurd to me.

I’ll end this simply by citing some provocative statements made in the article’s comments thread—provocative not because I agree with them but because they’re well-positioned to spark debate. I’ll quote these here, unedited, and let people discuss this for themselves.

—The Bartlett “seem to want to be an architecture school and a school of alternate visual media culture at the same time. More often than not these agendas work against each other… They should make a choice and be clear about it. Are you training students to be architects or something else that has to do with architecture? What should a student expect to learn when they finish school? What are you being prepared for. If bartlett graduates go on to become film-makers, and video game designers, and such, maybe its a good idea to say it is not an architecture school and say it is a school of visual media. Then you will attract students with that goal in mind.”

—From the same commenter: “Consider, if a school opens up and starts teaching alternative medicine (acupuncture, aromatherapy, Atkins diet, chiropractic medicine, herbalism, breathing meditation, yoga,etc), gives its graduates medical degrees and sent them off to hospitals and emergency rooms to perform surgery, a lot of people would have a problem with that. This is, in effect, what the architectural profession is doing when it allows schools like the Bartlett to give architecture degrees.”

—”architectural education is still a leftover of that idea of the businessman/artiste producing unusual shapes for art critics”

—”The profession does not work. It’s economically non viable. Our work is pure iteration. Far too time consuming, and as a result, it’s impossible to charge anyone for the work we have actually done.”

And on we go…

(Spotted via @brandavenue and @ArchitectureMNP).

[Image: From Amphibious Architecture; photo by Chris Woebken].

[Image: From Amphibious Architecture; photo by Chris Woebken]. [Image: From Amphibious Architecture; photo by Chris Woebken].

[Image: From Amphibious Architecture; photo by Chris Woebken].

[Image: From Amphibious Architecture; photo by Chris Woebken].

[Image: From Amphibious Architecture; photo by Chris Woebken]. [Image: The Sutro

[Image: The Sutro  [Image: A photo-collage from Splitting by Gordon Matta-Clark].

[Image: A photo-collage from Splitting by Gordon Matta-Clark]. [Image: “Moravian Mount” from

[Image: “Moravian Mount” from

[Images: From

[Images: From  [Image: From

[Image: From

[Images: From

[Images: From

[Images: “House of Drink,” “Greenhouse,” and town plan from

[Images: “House of Drink,” “Greenhouse,” and town plan from

[Image: From

[Image: From

[Images: From

[Images: From

[Images: From

[Images: From  [Image: Michael Light, Bingham Pit photograph mounted and on display].

[Image: Michael Light, Bingham Pit photograph mounted and on display]. [Image: Two photos from

[Image: Two photos from  [Image: Michael Light, “Garfield Stack, Oquirrh Mountains and Ancient Beach of Great Salt Lake” (2006)].

[Image: Michael Light, “Garfield Stack, Oquirrh Mountains and Ancient Beach of Great Salt Lake” (2006)]. [Image: “Oops” by

[Image: “Oops” by  [Image: From Rem Koolhaas’s unbuilt proposal for the Parc de la Villette in Paris, via

[Image: From Rem Koolhaas’s unbuilt proposal for the Parc de la Villette in Paris, via  [Image: From a project by

[Image: From a project by  [Image:

[Image:  [Image: Six of Amazon.com’s

[Image: Six of Amazon.com’s  [Image: The cooling towers of the

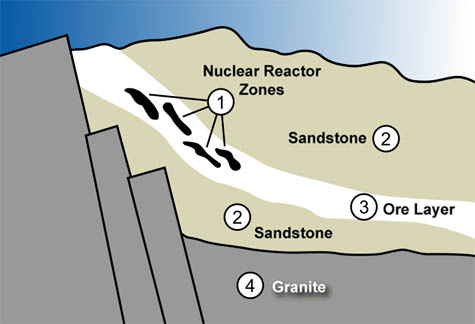

[Image: The cooling towers of the  [Image: The natural clocks and ticking stratigraphy of the Oklo uranium deposit, courtesy of the

[Image: The natural clocks and ticking stratigraphy of the Oklo uranium deposit, courtesy of the  [Image: A diagram of the Oklo uranium deposit, courtesy of the U.S.

[Image: A diagram of the Oklo uranium deposit, courtesy of the U.S.