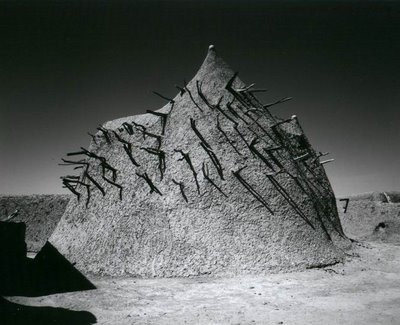

[Image: Tambeni Mosque; Sebastian Schutyser, 2001].

[Image: Tambeni Mosque; Sebastian Schutyser, 2001].

Belgian photographer Sebastian Schutyser spent nearly four years photographing the mud mosques of Mali. A collection of 200 such black & white photographs is now online at ArchNet.

The project “began in 1998,” Schutyser explains: “For several months I traveled from village to village by bicycle and ‘pirogue’, navigating with IGN 1:200.000 maps. The inaccessibility of the area made me realize why this hadn’t been done before.”

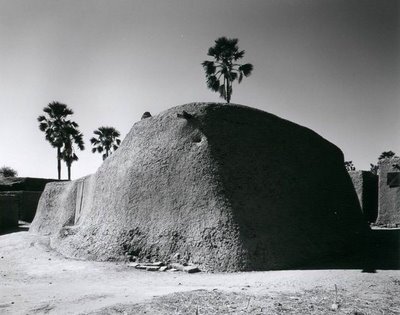

[Images: (top) Noga Mosque, (bottom) Tenenkou Mosque; Sebastian Schutyser, 2001].

[Images: (top) Noga Mosque, (bottom) Tenenkou Mosque; Sebastian Schutyser, 2001].

Within a few years, however, and over a period lasting roughly till the Spring of 2002, Schutyser managed “to travel faster, and reach the most remote parts of the Inner Delta. To increase the documentary value of the collection, I worked with 35mm color slides, and photographed every mosque from different angles. Whenever I encountered a particularly pretty mosque, I also photographed it on 4-5 inch black & white negative, to add to the ‘vintage’ collection.”

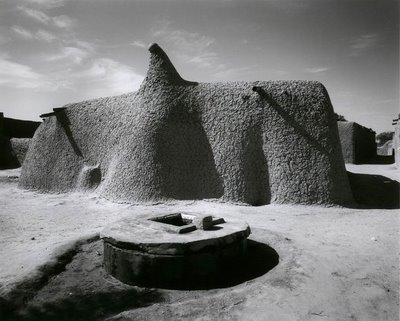

[Images: (top) Sébi Mosque, (bottom) Tilembeya Mosque; Sebastian Schutyser, 1998].

[Images: (top) Sébi Mosque, (bottom) Tilembeya Mosque; Sebastian Schutyser, 1998].

“With 515 mosques photographed,” Schutyser writes, “this collection shows a representative image of the adobe mosques of the Niger Inner Delta. Advancing modernity, and a lack of appreciation for this ‘archaic’ approach to building, are serious threats to the continuity of this living architecture.”

I might also add that each building is a kind of ritually re-repaired ventilation machine capable of generating its own microclimate: “During the day,” ArchNet explains, “the walls absorb the heat of the day that is released throughout the night, helping the interior of the mosque remain cool all day long. Some structures, for example, Djenné’s Great Mosque, also have roof vents with ceramic caps. These caps, made by the town’s women, can be removed at night to ventilate the interior spaces. Masons have integrated palm wood scaffolding into the building’s construction, not as beams, but as permanent scaffolding for the workers who apply plaster annually during the spring festival to restore the mosque. The palm beams also minimize the stress that comes from the extreme temperature and humidity changes typical of the climate.”

Finally, each tower is “often topped with a spire capped by an ostrich egg, symbolizing fertility and purity.”

Schutyser’s images have been collected in a beautiful book, co-written with Dorothee Gruner and Jean Dethier, called Banco: Adobe Mosques of the Inner Niger Delta.

[Image: Sinam Mosque; Sebastian Schutyser, 2002].

[Image: Sinam Mosque; Sebastian Schutyser, 2002].

(All images in this post are ©Sebastian Schutyser).