[Image: A cable car connects Europe and Africa, by Fabio Tozzoli and Eliana Salazar, Bologna (Italy); via Domus].

[Image: A cable car connects Europe and Africa, by Fabio Tozzoli and Eliana Salazar, Bologna (Italy); via Domus].

Back in May, the revitalized Domus magazine asked to see “your ideas for a connection between Africa and Europe across the Strait of Gibraltar,” suggesting in the process that the best results might be a “Bridge? Tunnel? Cablecar? Dam? Metropolis? Market? Power plant? Museum? Icon? Prison? Park? Airport?”

Perhaps all (or none) of the above.

[Image: Walking alone through the precarious geopolitical space between Europa and Africa, by Gabriele Garavaglia (Italy); via Domus].

[Image: Walking alone through the precarious geopolitical space between Europa and Africa, by Gabriele Garavaglia (Italy); via Domus].

Of course, viewed simply on the level of geography, this is no ordinary crossing. As Domus points out, “a tunnel would have to overcome engineering challenges far greater than those faced by the Eurotunnel’s designers: the water is exponentially deeper (nearly 1 km at the shortest point across the strait, compared with just 70 metres in the English Channel).” A bridge wouldn’t be much better, as any such proposal “must take into account the presence of heavy east-west marine traffic, and its piers must be able to withstand ship collisions and high winds.” On the other hand, “an underwater ‘mountain’ exists at the center of the strait’s narrowest section,” and this “could be used to divide the bridge’s span in two”—but, unfortunately, “the location of the crossing coincides with an active fault of the African and the Eurasian tectonic plates.”

Even this, though, is well before the harrowing reality of a trans-Mediterranean crossing has been politically improved for so many of those who attempt to make it. Indeed, as one response suggests, there are “a lot of things to think about before building a massive bridge between two different worlds”—indeed, “dialogue is the solution” to international relations around the Mediterranean Sea, not some Herculean piece of half-baked infrastructure.

No matter how you look at it, then, it seems an architectural connection between the continents is not only difficult, it is perhaps impossible.

[Image: The Eurafrican maritime border as “geostrategic platform,” by Gabriel Esteban Duque, Juan Miguel Gómez, Maria Isabel González, Medellín (Colombia); via Domus].

[Image: The Eurafrican maritime border as “geostrategic platform,” by Gabriel Esteban Duque, Juan Miguel Gómez, Maria Isabel González, Medellín (Colombia); via Domus].

However, that’s exactly the kind of challenge that design increasingly thrives on, and over the past two months an extraordinary collection of postcards has been arriving at the Domus offices in Milan, responding to this call for ideas. These potential continental connections have fallen into a few dozen categories, including:

21 Islands and archipelagos

10 Ship chains

6 Bridge-cities

6 Red Sea [Biblical partings-of-the-water]

5 Bridges suspended with air ballons

4 Tensile structures

4 Funiculars

4 Tightropes

3 Rainbows

3 Markets

3 Airships

2 Underwater bridges

2 Roller coasters

2 Tunnels

1 No bridge

1 Geoengineering

1 Shopping mall

1 Zebra crossing

1 New continent

1 Swimming Pool

And this still doesn’t tally the full run of ideas coming in from all over the world (in fact, you have till 19 July to submit your own). A suite of 300 different responses will be on display starting at 7pm, Thursday, 21 July 2011—with free drinks—at the Gopher Hole in London. See the Gopher Hole’s website for more info.

[Image: Europe and Africa perhaps sarcastically joined by a bridge of colored balloons, by Pat and Luca Architecture, Melbourne (Australia); via Domus].

[Image: Europe and Africa perhaps sarcastically joined by a bridge of colored balloons, by Pat and Luca Architecture, Melbourne (Australia); via Domus].

One entry in particular, seen here for the first time courtesy of Domus, seems worthy of comment: a new international currency designed by architect Bjarke Ingels of BIG. 100 samples of Bjarke’s new infrastructurally-themed currency will be printed on banknote paper and given out at the event, so it’s worth stopping by if for no other reason than to collect counterfeit money designed by one of today’s most widely recognized architects.

[Images: The 1,000 Afro note by Bjarke Ingels].

[Images: The 1,000 Afro note by Bjarke Ingels].

These are the 1,000 EURO note and the 1,000 AFRO note.

[Images: A new 1,000 Euro note by Bjarke Ingels].

[Images: A new 1,000 Euro note by Bjarke Ingels].

As BIG explains:

BIG has designed a 1000 EURO bill and a corresponding 1000 AFRO bill as a first proposal for a United African Currency—the AFRO.

The two bills portray the proposed connection across the Gibraltar Strait linking Europe and Africa. The bridge is conceived as an inhabited overpass uniting Euro-African typologies—such as Firenze’s Ponte Vecchio and Le Corbusier’s Obus Plan for Algiers—into an intercontinental hybrid of city and infrastructure. The investment in concrete and steel doubles as load-bearing structure for living and working spaces for the many immigrants anticipated over the next decades, and will help establish the bridge itself as a bicontinental city in its own right.

The EURO bill draws on the current design template, emphasizing architecture as the common denominator between the various European cultures.

The AFRO combines great African landmarks—in this case, the bridge—with great African people of recent history who have contributed significantly to making a free united Africa a possibility.

Briefly, I’m reminded of a student project from 2008 called Our New Capitol, by Bryan Boyer. For that project, Boyer asked what sort of congressional meetinghouse would be most appropriate for U.S. governance in the 21st century, but also what that country’s currency should look like.

[Image: From Our New Capitol by Bryan Boyer].

[Image: From Our New Capitol by Bryan Boyer].

Or, of course, there is the famous Dutch architecture coin by Stani Michiel:

[Image: Speculative numismatics by Stani Michiel].

[Image: Speculative numismatics by Stani Michiel].

The idea that a nation—or an inter-nation, as it were, formed by a crossing between Europe and Africa—deserves its most representationally accurate currency is a compelling one, as is the idea that architects and designers could start issuing their own banknotes as geopolitical provocations, simply to see what happens next.

Of course, if we’re going to take this experiment seriously, then we should perhaps ask why it is worth including one of Bjarke’s own earlier buildings on the notes—as you’ll see, above, the 1,000 EURO features the VM Houses, designed by Bjarke Ingels and Julien De Smedt—although this is fairly obviously a joke. And, further, I would love to see a 500, 100, 50, etc., AFRO note, simply to rest assured that the architect doesn’t really believe this bridge is the single “great African landmark” worthy of monetary representation.

But, putting those criticisms aside, BIG’s money is a useful launching point for wondering aloud what we could do, as architects, designers, writers, artists, and more, to rethink the accoutrements of the nation-state, from passports to parking tickets, and thus how we might reconsider, down to the smallest details, how the State, writ large, is understood and presented.

That is, how can we redesign the geopolitical ephemera through which nation-states currently recognize each other, and how might these sorts of peripheral—even frivolous—interventions inspire real constitutional change elsewhere? To put this in spatial terms: what is the architecture of the post-nation-state? And what sorts of infrastructure might the future of governance require? (See, for example, Pier Vittorio Aureli’s Brussels: A Manifesto Towards the Capital of Europe for a provocative look at how urban design can help to implement a transnational system of governance such as the European Union).

Altering the order of emphasis here, perhaps it is time to prioritize the wholesale redesign of nation-states as a central problem for the 21st century, whether that means redrawing international (or intranational) borders around natural resources, such as this alternative map of the western U.S. produced by John Wesley Powell—

[Image: A hydrocentric alternative to today’s western geopolitical boundaries by John Wesley Powell; see the excellent book Cadillac Desert by Marc Reisner for more on Powell].

[Image: A hydrocentric alternative to today’s western geopolitical boundaries by John Wesley Powell; see the excellent book Cadillac Desert by Marc Reisner for more on Powell].

—in which the outer limits of U.S. states are determined not by human demographics but by watersheds. Or perhaps we should more aggressively rethink the future of governance and national validity through such things as literary works—through novels like Paul Auster’s Man in the Dark, Rupert Thomsen’s Divided Kingdom, or Anna North’s America Pacifica—or even through games, such as the underwhelming and jingoistic Homefront.

More to the point, could we use Domus‘s Project Heracles to open the door to other, equally radical possibilities for geopolitical redesign; where do these possibilities now most urgently exist (Israel/Palestine? the Bering Strait? the U.S./Mexico border?); and what is the most useful way for architects and designers to catalyze new forms of human governance?

Do we start with counterfeit money or do we build new geographies altogether?

In any case, be sure to stop by the opening party at the Gopher Hole in London on Thursday night—and keep your eye out for Bjarke Ingels’s new cash.

[Image: The weather bowl at Moray, Peru; photo by Ian Wood/Alamy, courtesy of National Geographic].

[Image: The weather bowl at Moray, Peru; photo by Ian Wood/Alamy, courtesy of National Geographic]. [Image: From Sietch Nevada by Matsys; renderings by Nenad Katic].

[Image: From Sietch Nevada by Matsys; renderings by Nenad Katic].

[Image: A cable car connects Europe and Africa, by Fabio Tozzoli and Eliana Salazar, Bologna (Italy); via

[Image: A cable car connects Europe and Africa, by Fabio Tozzoli and Eliana Salazar, Bologna (Italy); via  [Image: Walking alone through the precarious geopolitical space between Europa and Africa, by Gabriele Garavaglia (Italy); via

[Image: Walking alone through the precarious geopolitical space between Europa and Africa, by Gabriele Garavaglia (Italy); via  [Image: The Eurafrican maritime border as “geostrategic platform,” by Gabriel Esteban Duque, Juan Miguel Gómez, Maria Isabel González, Medellín (Colombia); via

[Image: The Eurafrican maritime border as “geostrategic platform,” by Gabriel Esteban Duque, Juan Miguel Gómez, Maria Isabel González, Medellín (Colombia); via  [Image: Europe and Africa perhaps sarcastically joined by a bridge of colored balloons, by Pat and Luca Architecture, Melbourne (Australia); via

[Image: Europe and Africa perhaps sarcastically joined by a bridge of colored balloons, by Pat and Luca Architecture, Melbourne (Australia); via

[Images: The 1,000 Afro note by

[Images: The 1,000 Afro note by

[Images: A new 1,000 Euro note by

[Images: A new 1,000 Euro note by  [Image: From

[Image: From  [Image: Speculative numismatics by

[Image: Speculative numismatics by  [Image: A hydrocentric alternative to today’s western geopolitical boundaries by John Wesley Powell; see the excellent book

[Image: A hydrocentric alternative to today’s western geopolitical boundaries by John Wesley Powell; see the excellent book

[Image: From a press pack released last month by

[Image: From a press pack released last month by

[Image: A collage of various buildings by Robert Scarano, from photos by

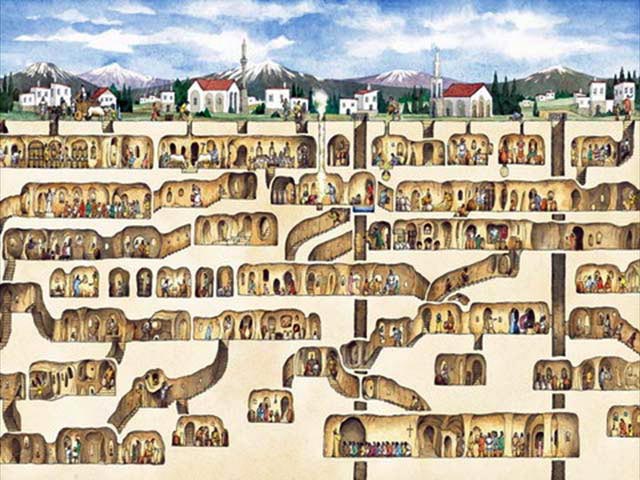

[Image: A collage of various buildings by Robert Scarano, from photos by  [Image: The underground city of

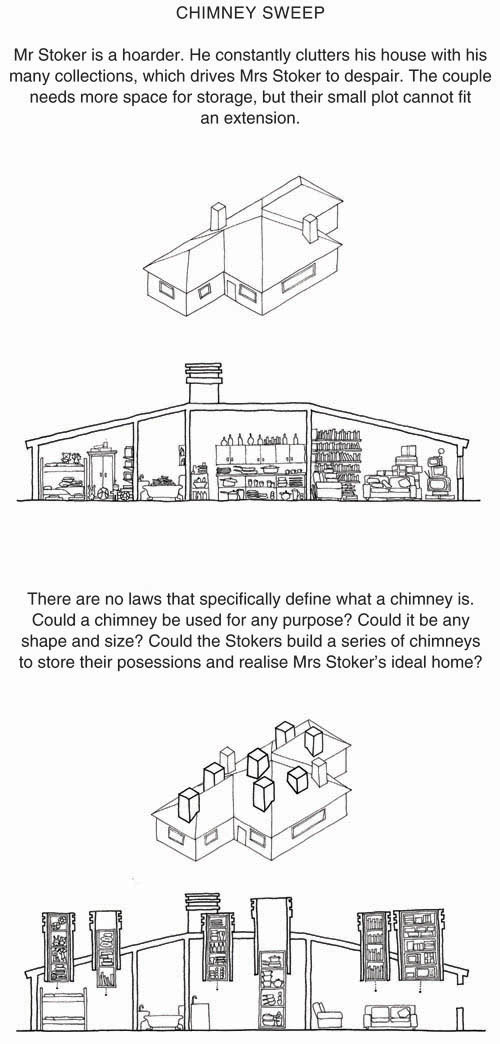

[Image: The underground city of  [Image: From

[Image: From

[Image:

[Image:

[Image: The “

[Image: The “

[Images: The “

[Images: The “

[Images: The “

[Images: The “

[Images: The “

[Images: The “ [Images: The “

[Images: The “

[Images: The “

[Images: The “

[Image: Allied bombers in World War 2; via

[Image: Allied bombers in World War 2; via

[Image: The infrastructure of

[Image: The infrastructure of  [Image: “

[Image: “