Considering the image that’s been sitting up on top of the righthand column here for several months now, it might be hard to have missed the fact that there’s a BLDGBLOG Book coming out. However, it also might not be entirely clear what the book is about, what’s in it, or even who it’s for; it might not be clear, in other words, why you should consider reading it.

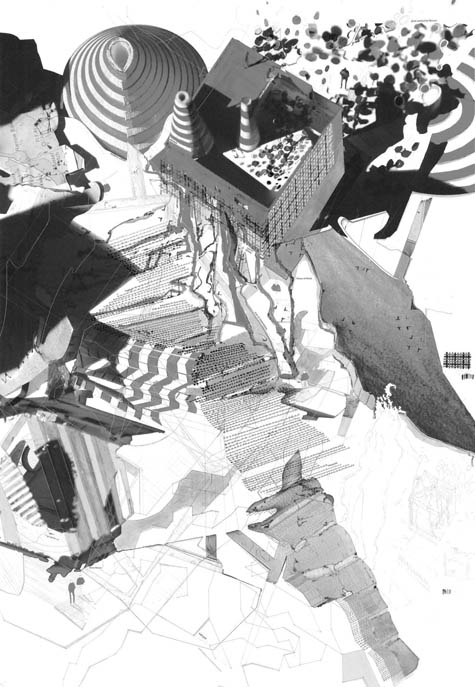

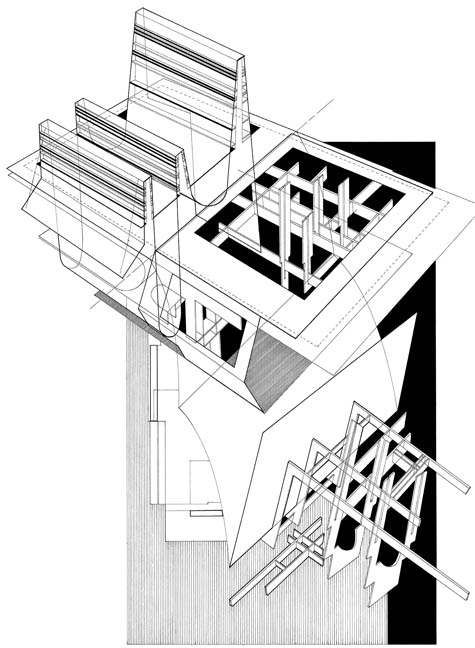

[Image: An illustration by Brendan Callahan, from The BLDGBLOG Book].

[Image: An illustration by Brendan Callahan, from The BLDGBLOG Book].

I thought, then, as the book is now shipping around the world and there’s even an official launch party tomorrow night at the Architectural Association in London, that there’s never been a better time to give everybody a quick tour through the book’s major highlights.

So here is a typically internet-ish list of ten reasons why you should read The BLDGBLOG Book.

1) The book itself! There are nearly 300 pages, close to 115,000 words, and approximately 275 images – and the whole thing is crammed full of sidebars, long captions, running text, and interstitial chapters scattered like blog posts in between. While you could sit down and read the whole thing through in two or three sittings, most likely it will become something you can turn to again and again – at the beach, in the studio, on an airplane flight – to look for ideas, visual inspiration, or even just a list of further things to read.

Write notes in the margins. Google things you’d never heard of before. Reread a few sections.

Option certain ideas for future blockbuster films…

There’s so much content in The BLDGBLOG Book that there’s undoubtedly something for everyone: buildings, myths, gadgets, and paintings, short stories, maps, and comics, Mars photography, Gothic horror, and brand new interviews. It’s got 19th-century ruins paintings, artificial glaciers, and countless speculative projects by some of today’s most exciting architects – among a hundred thousand other things that will hopefully keep you coming back to the book for a long time to come.

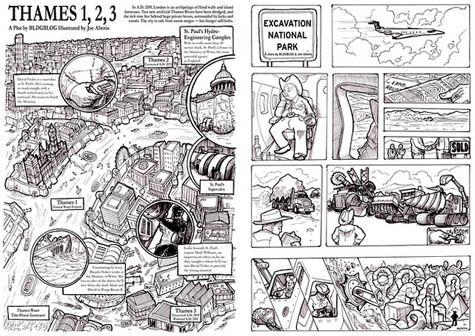

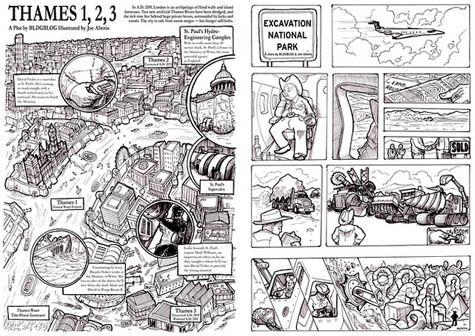

[Images: Two original comic strips by Joe Alterio and BLDGBLOG for The BLDGBLOG Book].

[Images: Two original comic strips by Joe Alterio and BLDGBLOG for The BLDGBLOG Book].

2) For years now I’ve suggested that architectural ideas can be articulated, often extraordinarily well, in the form of graphic novels and comic books – so it seemed like I should finally try that theory out for myself. The book thus comes with two original comic strips, created in collaboration with San Francisco-based illustrator Joe Alterio: “Thames 1, 2, 3” and “Excavation National Park.” They’re featured on the inside covers, one of them without words, the other a much longer scenario in which most of London is underwater, transformed into “an archipelago of flood walls and island fortresses.” There are Conradian references and tide-energy machines.

Joe’s artwork, I have to say, is stunning – it’s precise and clean, yet tightly energetic – and, with any luck, he and I will be working together again in the future. (Joe also designed the logo for Postopolis! LA).

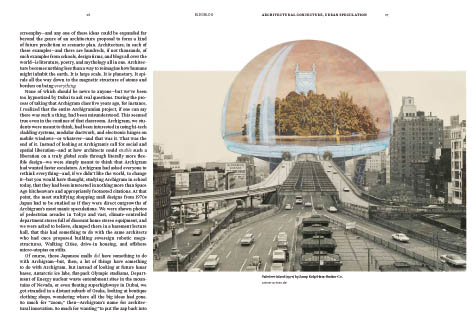

[Image: An illustration by Brendan Callahan, from The BLDGBLOG Book].

[Image: An illustration by Brendan Callahan, from The BLDGBLOG Book].

3) The book also has dozens of full-color, original illustrations by Brendan Callahan, a friend and former coworker. Brendan and I spent many a lunchtime break together back in San Francisco going over preliminary sketches and ideas for the book – and I think he hit the ball right out of the park here, coming back at the end, after sometimes excruciatingly vague art direction from yours truly (sorry, Brendan!), with detailed and very witty full-page images: architectural reefs, domesticated Northern Lights, endangered geological formations, underground cities, sound mirrors, overgrown freeways, hot air balloon concerts of subliminal nighttime music, buttressed buttresses, and even Miesian prescription drugs…

For Brendan’s illustrations alone, the book is well worth picking up.

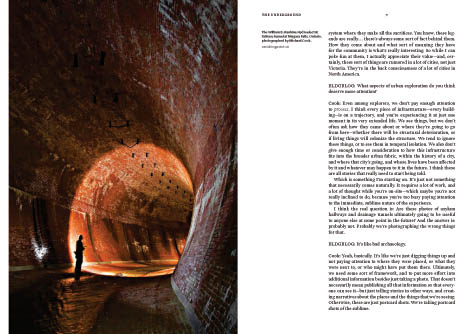

4) The book is dotted with awesome interviews – from edited versions of BLDGBLOG’s earlier discussions with classicist Mary Beard, urban explorer Michael Cook, theorist and historian Mike Davis, game designer Daniel Dociu, photographer David Maisel, novelist Patrick McGrath, photographer Simon Norfolk, and writer Jeff VanderMeer, to an expanded interview with architect Lebbeus Woods – discussing his project “Einstein Tomb,” Arthur C. Clarke’s novel Rendezvous with Rama, and much more.

Beyond that, there are brand new, exclusive, and otherwise unpublished interviews with Archigram co-founder Sir Peter Cook, architect and writer Sam Jacob, musician DJ /rupture, urban games entrepreneur Kevin Slavin, and author Tom Vanderbilt. There are even short email interviews with fellow bloggers Bryan Finoki and Alexander Trevi, as well as with photographers Stanley Greenberg and Richard Mosse – lending the book so many other voices that, even if you don’t like my own particular take on things, it should be easy enough to find a perspective here that appeals to you.

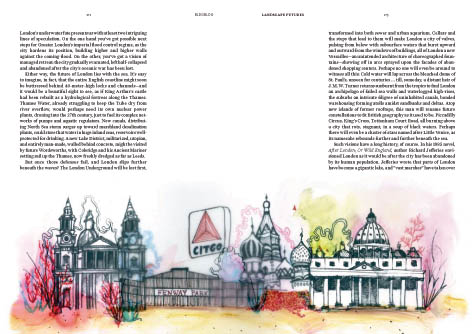

[Images: Spreads from The BLDGBLOG Book].

[Images: Spreads from The BLDGBLOG Book].

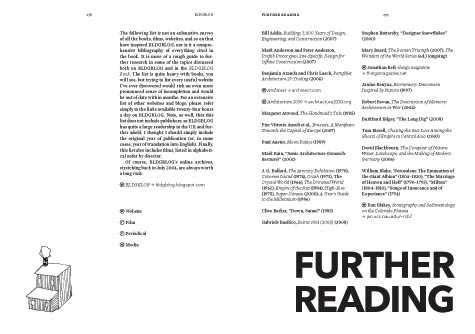

5) The book wouldn’t be half as visually interesting as it I think it’s turned out to be without the eye-popping photography of Edward Burtynsky, Michael Cook, Emiliano Granado, Stanley Greenberg, Ilkka Halso, David Maisel, Richard Mosse, Simon Norfolk, Bas Princen, Siologen, and many, many others (including NASA, the United States Navy, and the Army Corps of Engineers).

All of even that, however, is in addition to architectural projects from Smout Allen, Agents of Change, Archigram, ArandaLasch, Minsuk Cho & Jeffery Inaba, FAT, Vicente Guallart, Lateral Office, Studio Lindfors, LOT-EK, Andrew Maynard, Haus-Rucker-Co., Joel Sanders, and Iwamoto Scott – and there are posters by Steve Lambert and Packard Jennings, video game environments by Daniel Dociu, “spam architecture” by Alex Dragulescu – and the list goes on and on.

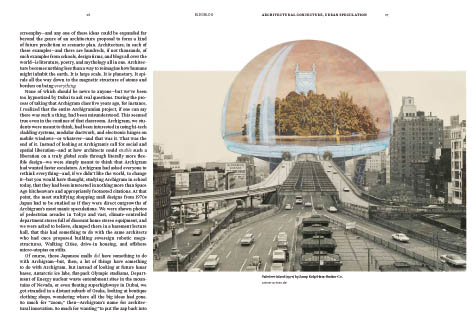

[Image: A spread from The BLDGBLOG Book, designed by MacFadden & Thorpe].

[Image: A spread from The BLDGBLOG Book, designed by MacFadden & Thorpe].

6) The book is beautifully designed by MacFadden & Thorpe – with a clear and legible use of the page grid, great font choices (including Avenir, which you see in BLDGBLOG’s logo), full-bleed images, and different-colored paper.

It’s a solid book: it looks and feels great, and it’s durable.

Designers Brett MacFadden and Scott Thorpe worked down to the tiniest level of detail to get it all lined up and functioning; Scott and I, in particular, often met after work last year at MacFadden & Thorpe’s Mission studio to go over the book, page by page – a fantastic way to put together a project like this.

One minor design detail that I like, for instance, becomes apparent after you shelve the book: the spine itself contains the table of contents.

7) It’s probably not entirely surprising that I might have one or two good things to say about the book, having spent so much time working on it – but I’m not the only one. Here’s a brief sample of what other people think of The BLDGBLOG Book…

The back-cover blurbs come from Academy Award-winning director Errol Morris; Jeff Gordinier, Editor-at-Large of DETAILS magazine and author of X Saves the World; Justin McGuirk, Editor-in-Chief of Icon; Lawrence Weschler, National Book Critics Circle Award-winning author of, among many other things, Mr. Wilson’s Cabinet Of Wonder; Joseph Grima, executive director of New York’s legendary Storefront for Art and Architecture; and Sarah Rich, managing editor of the Worldchanging book.

Meanwhile, just this past weekend, The Guardian wrote that the book has a “Wellsian ability to conjure up the structures and spaces of the future,” and that it “fizzes with new ideas about the architecture that frames our lives.”

Literally tonight, then, as I sat down to read back through this post on a quest for lame phrases or typos, Amazon.com announced that The BLDGBLOG Book is one of their “Best Hidden Gems of 2009… So Far” – calling it a “gorgeous object” that will “build a new room in your brain.”

Wired enthusiastically recommends that you read it – as does Dwell – and SEED Magazine has called it one of their “Books to Read Now,” adding that The BLDGBLOG Book‘s “freewheeling explorations of how we may come to interact with our buildings, our cities, and our planet draw from every branch of science (plus a few from science fiction).”

Allison Arieff calls it “highly recommended reading.”

Obviously, not everyone in the world is going to like the book – and if you don’t, of course, let me know what you think in the comments – but hopefully these are a good indication that the book has been put together well.

[Image: The beginning of the Further Reading list, from The BLDGBLOG Book].

[Image: The beginning of the Further Reading list, from The BLDGBLOG Book].

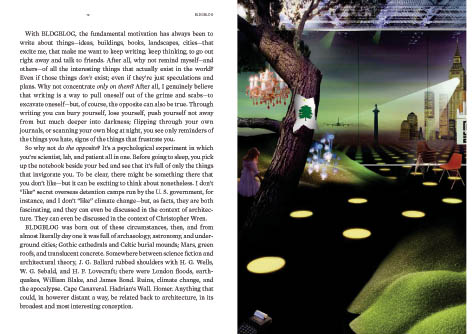

8) Toward the end of the book is an extensive “Further Reading” list, mostly referring to print media (I decided that a list of blogs and websites would rapidly become obsolete, as they come and go so quickly). However, this is a solid reading (and viewing) list, encompassing everything from Foucault’s Pendulum to Ghostbusters, Bunker Archeology and William Burroughs to Giordano Bruno and Alfred Hitchcock, Piranesi to Papillon.

The only down side, of course, is that I already have a half-dozen things I’d like to add – for instance, John Christopher’s Death of Grass and Kaputt by Curzio Malaparte – but that’s life.

If you are at all curious about which books, films, and magazines (and even a few websites) are being consumed behind the scenes here at BLDGBLOG, there’s no better place to start than The BLDGBLOG Book‘s long list of Further Reading. Photocopy it and give it to friends. Or read your way through it, checking off titles one by one.

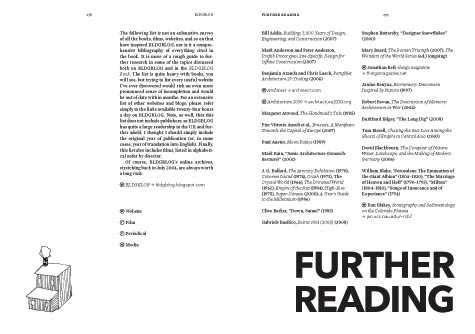

[Image: The Autographs page, from The BLDGBLOG Book].

[Image: The Autographs page, from The BLDGBLOG Book].

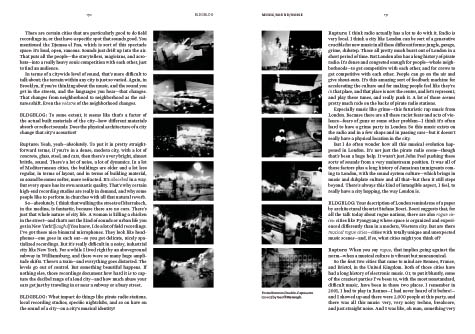

9) Coming just after the Further Reading list there is… the Autographs page.

This is where you can ensure your copy of The BLDGBLOG Book becomes totally unique to you, as each copy comes with pre-labelled spaces in which to collect certain autographs… by Lebbeus Woods, Walter Murch, Siologen, Steven Spielberg, Rachel Whiteread, and even Brad Pitt. Why not?

Now Brad Pitt, for instance, is all but guaranteed to be confronted someday with a copy of The BLDGBLOG Book – and if you ever decide to get rid of the thing it will be worth $500 on eBay. Value-added!

Unfortunately it’s now impossible for anyone to get every name signed – with the death of novelist J.G. Ballard – but it would be genuinely interesting to see who can fill up the autographs fastest. Going to Denmark on holiday? Well, bring along The BLDGBLOG Book in case you run into Bjarke Ingels. Headed for Los Angeles? Better bring The BLDGBLOG Book – and stop by CLUI or SCI-Arc to get signatures from Matthew Coolidge and Mary-Ann Ray…

10) Finally, why should you read The BLDGBLOG Book? Again, because of the content.

There are so many interesting things in there, from tectonic maps of the earth’s evolving surface to previously unpublished documentation of a campaign to stabilize geological forms in Utah using spray-on adhesives manufactured by the automobile industry. There are acoustically sophisticated underground cities accidentally discovered by rural farmers and there are U.S. military plans for the weaponization of hurricanes. There is the flooded London of the 27th century and there is the deliberate demolition of architecture as an act of international war.

Lost film sets, space seeds, and Stalinist sleep labs sit beside occupied cities and flying orchestras; fossil rivers flow by rogue adventure tourism firms, hydrological models, and the groaning sounds of climate-changed glaciers.

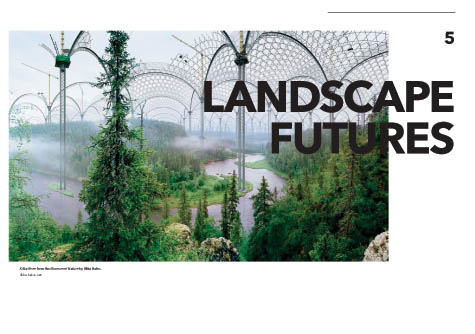

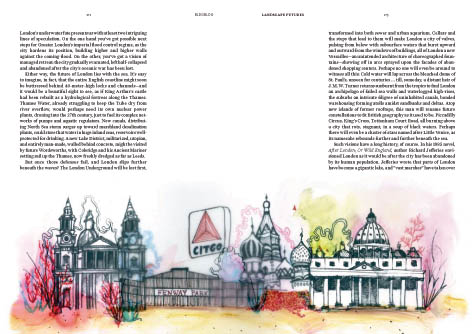

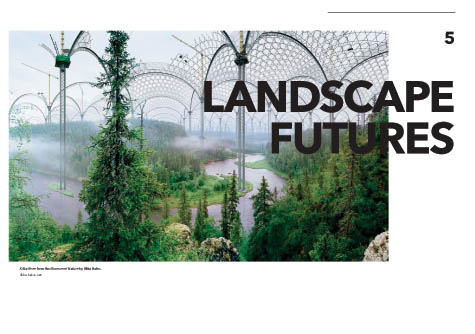

There are buildings, speculative cities, and landscape futures.

[Image: A spread from The BLDGBLOG Book, featuring a photograph by Ilkka Halso].

[Image: A spread from The BLDGBLOG Book, featuring a photograph by Ilkka Halso].

So check it out if you get a chance – I hugely appreciate any and all interest in the book. If you’ve bought a copy already, of course, I owe you a genuine thanks!

And, again, if you’re in London on Tuesday, 7 July, from 6-8pm, I’d love to see you at The BLDGBLOG Book‘s official launch party at the Architectural Association.

Launching just today is an awesome new ideas competition called Reburbia.

Launching just today is an awesome new ideas competition called Reburbia. Co-sponsored by Inhabitat, the contest’s judges are Jill Fehrenbacher, Sarah Rich, Fritz Haeg, Paul Petrunia, Thomas Ermacora, Allan Chochinov, and myself. It’s a fantastic group of people to be with, I have to say, and I can’t wait to see how people respond.

Co-sponsored by Inhabitat, the contest’s judges are Jill Fehrenbacher, Sarah Rich, Fritz Haeg, Paul Petrunia, Thomas Ermacora, Allan Chochinov, and myself. It’s a fantastic group of people to be with, I have to say, and I can’t wait to see how people respond.  [Image: From

[Image: From  [Image: An illustration by

[Image: An illustration by  [Images: Two original comic strips by

[Images: Two original comic strips by  [Image: An illustration by

[Image: An illustration by

[Images: Spreads from

[Images: Spreads from  [Image: A spread from

[Image: A spread from  [Image: The beginning of the Further Reading list, from

[Image: The beginning of the Further Reading list, from  [Image: The Autographs page, from

[Image: The Autographs page, from  [Image: A spread from

[Image: A spread from  [Image: Photo by

[Image: Photo by  [Image: The “House of Drink” by

[Image: The “House of Drink” by  [Images: A display of

[Images: A display of  [Image: From “The Survey of London” by Will Jefferies,

[Image: From “The Survey of London” by Will Jefferies,  [Image: A Greenland ice-core at the

[Image: A Greenland ice-core at the  [Image: A satellite view of the city-block core sample, via

[Image: A satellite view of the city-block core sample, via  [Image: A fragment of the Forma Urbis, showing the Balbi Theater. For more on the Forma Urbis, visit the seemingly great but non-Mac-friendly

[Image: A fragment of the Forma Urbis, showing the Balbi Theater. For more on the Forma Urbis, visit the seemingly great but non-Mac-friendly  [Image: Museum display panel diagramming five distinct road levels wandering across the Crypta’s ruins (apologies for the quick snapshot)].

[Image: Museum display panel diagramming five distinct road levels wandering across the Crypta’s ruins (apologies for the quick snapshot)]. [Image: An interior view of the

[Image: An interior view of the  [Image: From OnSite.12, Bed Supperclub, Bangkok (2009) by

[Image: From OnSite.12, Bed Supperclub, Bangkok (2009) by  [Image: From OnSite.12, Bed Supperclub, Bangkok (2009) by

[Image: From OnSite.12, Bed Supperclub, Bangkok (2009) by  [Image: From OnSite.14, Transmediale, Berlin (2009), by

[Image: From OnSite.14, Transmediale, Berlin (2009), by  [Image: From OnSite.14, Transmediale, Berlin (2009), by

[Image: From OnSite.14, Transmediale, Berlin (2009), by  [Image: All systems go… Original photo by Jim Grossman, courtesy of

[Image: All systems go… Original photo by Jim Grossman, courtesy of  [Image: Photo of the Atlantic Avenue train tunnel taken by

[Image: Photo of the Atlantic Avenue train tunnel taken by  [Image: Lightning storm over Boston, ca. 1967; photo courtesy of

[Image: Lightning storm over Boston, ca. 1967; photo courtesy of  [Image: A portrait of the

[Image: A portrait of the  [Image: The Chrysler Building – a sponsored building – montaged by Flickr-user

[Image: The Chrysler Building – a sponsored building – montaged by Flickr-user