In a fantastic interview published last year by the Wall Street Journal, novelist Cormac McCarthy—quipping off-hand that “anything that doesn’t take years of your life and drive you to suicide hardly seems worth doing”—reflects on what might or might not have caused the world-ending catastrophe that frames his recent book The Road.

The Road, of course, takes place in a relentlessly grey world, populated only by a father and his son. The anemic duo walks slowly south toward an unidentified coast over mountains and plains, through valleys and dead forests; everything is burned, molten, or obliterated. The father is coughing blood. They meet cannibals and the insane, and they stray into abandoned houses less uninhabited than they seem.

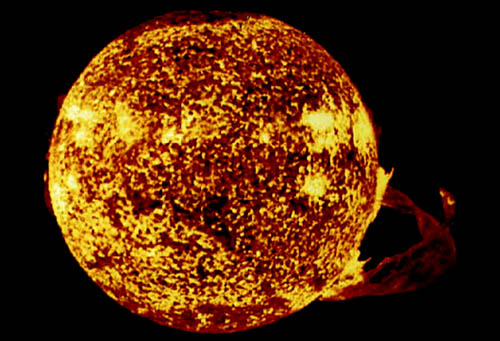

[Image: Grand Prismatic Spring, Yellowstone National Park, Wyoming].

The only glimpse we’re given of what violently ends the known order of things is this brief scene; I have left McCarthy’s original spelling and punctuation intact:

The clocks stopped at 1:17. A long shear of light and then a series of low concussions. He got up and went to the window. What is it? she said. He didnt answer. He went into the bathroom and threw the lightswitch but the power was already gone. A dull rose glow in the windowglass. He dropped to one knee and raised the lever to stop the tub and the turned on both taps as far as they would go. She was standing in the doorway in her nightwear, clutching the jamb, cradling her belly in one hand. What is it? she said. What is happening?

I dont know.

Why are you taking a bath?

I’m not.

After this, the landscape outside—everywhere—is described as “scabbed” and “cauterized,” heavily covered in ash. McCarthy memorably writes: “They sat at the window and ate in their robes by candlelight a midnight supper and watched distant cities burn.”

Later in his interview with the Wall Street Journal, McCarthy jokes that he and his brother once “talked about if there was a small percentage of the human population left [after a disaster], what would they do? They’d probably divide up into little tribes,” he and his brother decided, “and when everything’s gone, the only thing left to eat is each other. We know that’s true historically.”

In any case, McCarthy’s end-times scenario sounds, to me, remarkably like nuclear war, but in his interview McCarthy entertains, even if only casually, that it could also have been the caldera beneath Yellowstone National Park finally exploding. McCarthy:

A lot of people ask me [what caused The Road‘s apocalypse]. I don’t have an opinion. At the Santa Fe Institute I’m with scientists of all disciplines, and some of them in geology said it looked like a meteor to them. But it could be anything—volcanic activity or it could be nuclear war. It is not really important. The whole thing now is, what do you do? The last time the caldera in Yellowstone blew, the entire North American continent was under about a foot of ash. People who’ve gone diving in Yellowstone Lake say that there is a bulge in the floor that is now about 100 feet high and the whole thing is just sort of pulsing. From different people you get different answers, but it could go in another three to four thousand years or it could go on Thursday. No one knows.

It was thus amazingly interesting to read that no less than 1,799 earthquakes have occurred beneath Yellowstone since January 17, 2010—a so-called earthquake swarm.

As of yesterday, however, the USGS reports that the current swarm has “slowed considerably.” Indeed, we read, while “the current number of earthquakes per day is well above average at Yellowstone… nevertheless, swarms are common… with 100s to 1000s of events, some of which can reach magnitudes greater than 4.0.” In other words, it is always and already a landscape prey to internal lurching deformations and displacements, as if fabricated in a fever dream by Lebbeus Woods, torqued and aterrestrially tuned to some strange counter-timescale.

Swarms like this are, structurally speaking, quite common; this is a landscape always on the move—though it doesn’t necessarily travel far: “The crust beneath Yellowstone is highly fractured already,” a scientist told the New York Times, “so we’re getting stress release in these earthquakes—a displacement of millimeters.”

Still, when “the park’s strange and volatile geology,” with its thrumming subterranean supervolcano that is “bigger, much bigger, than scientists had previously thought,” kicked back into trembling motion, McCarthy’s “bulge in the floor that is now about 100 feet high and… just sort of pulsing,” a topographical sign of the apocalypse, instantly came to mind.